Joe Brown Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In Memoriam I Met Ralph in 1989 When I Moved to Wolverhampton, Through Our Involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- Eering Club

Obituaries Matterhorn. Edward Theodore Compton. 1880. Watercolour. 43 x 68cm. (Alpine Club Collection HE118P) 399 I N M E M ORI am 401 Ralph Atkinson 1952 - 2014 In Memoriam I met Ralph in 1989 when I moved to Wolverhampton, through our involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- eering Club. Weekends in Wales The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election and day trips to Matlock and the (including to ACG) Roaches became the foundation for extended expeditions to the Ralph Atkinson 1997 Alps including, in 1991, a fine Una Bishop 1982 six-day ski traverse of the Haute John Chadwick 1978 Route, Argentière to Zermatt, John Clegg 1955 and ascents in 1993 of the Mönch Dennis Davis 1977 and Jungfrau. Descending the Gordon Gadsby 1985 Jungfrau in a storm, we could Johannes Villiers de Graaff 1953 barely see each other. I slipped David Jamieson 1999 in the new snow and had to self- Emlyn Jones 1944 arrest, aided by the tension in the Brian ‘Ned’ Kelly 1968 rope to Ralph. It worked, and I Neil Mackenzie Asp.2011, 2015 Ralph Atkinson climbing on the slabs of Fournel, was soon back on the ridge, but Richard Morgan 1960 near Argentière, Ecrins. (Andy Clarke) when we dropped below the John Peacock 1966 Rottalsattel and could speak to Bill Putnam 1972 each other again, he had no idea that anything untoward had happened. Stephanie Roberts 2011 I recall long journeys by car enlivened by his wide-ranging taste in music. Les Swindin 1979 The keynote of many outings was his sense of fun. There were long stories, John Tyson 1952 jokes or pithy one-liners. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

Weatherman Walking Llanberis Walk

bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2013 Weatherman Walking Llanberis Walk Approximate distance: 4 miles For this walk we’ve included OS map coordinates as an option, should you wish to follow them. OS Explorer Map: OL17 5 6 4 8 3 10 9 1 Start End 2 N W E S Reproduced by permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of HMSO. © Crown copyright and database right 2009.All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence number 100019855 The Weatherman Walking maps are intended as a guide to help you walk the route. We recommend using an OS map of the area in conjunction with this guide. Routes and conditions may have changed since this guide was written. The BBC takes no responsibility for any accident or injury that may occur while following the route. Always wear appropriate clothing and 1 footwear and check weather conditions before heading out. bbc.co.uk/weathermanwalking © 2013 Weatherman Walking Llanberis Walk Walking information 1. Llanberis Lake Railway station (SH 58210 59879) The walk begins outside the Llanberis Lake Railway station and not at the popular Snowdonia Mountain Railway which is a little further along the A4086 towards the town centre. There is plenty of parking in and around the town near the Snowdon Mountain Railway and opposite Dolbadarn Castle. To begin the walk, follow the signs for Dolbadarn Castle and the National Slate Museum and opposite a car park turn right. Cross a large slate footbridge over the River Hwch and follow a winding track up through the woods to the castle. 2. Dolbadarn Castle (SH 58600 59792) The castle overlooking Llyn Peris was built by the Welsh prince Llewellyn the Great during the early 13th century, to protect and control the Llanberis Pass - a strategic location, protecting trade and military routes into north and south Wales. -

Climb99 Special Hillwalkers A-Z After Everest Technical Extra

Climb99 Special Be there 3-5 December Hillwalkers A-Z Gear, boots, winter After Everest Five decades of British Expeds. Technical Extra Conference, standards, PPE ACCESSACCESS NEWSNEWS WINWIN AA HIGHLANDHIGHLAND WEEKENDWEEKEND ALPINEALPINE BOLTSBOLTS KENYAKENYA ISSUE 15 AUTUMN '99 gripped?gripped? FREE TO ALL BMC MEMBERS £2.00 21821_Summit_15_Cover.p65 1 9/13/99, 9:40 AM FOREWORD.. SUMMITS OF DIVERSITY ust over six years ago the BMC’s Mountaineering Festival at the Buxton Opera House had the theme Jof Freedom. There was a strong line up of high- profile speakers, an exhibition, and an indoor bouldering league team challenge. Although not a sell-out, Buxton ‘93 was an enjoyable and memorable event. The event programme cover was a cartoon based on Delacroix’s famous painting of ‘Liberty guiding the people’ – only the BMC version had mountaineering luminaries at the barri- cade defending freedom of access. The Festival pro- gramme introduction talked about “the freedom to enjoy our cliffs and mountain environment” which it said “seem(ed) to be increasingly under threat”. As we come to the end of the 1990’s things have changed. It still appears to be universally accepted that access is the most important part of the BMC’s work - without access there is no climbing or hill walking. However, the careful evolution of the BMC’s Access Charter, lobbying of Government and developing partnerships with other relevant bodies, has created significant stepping stones towards improving an individual’s right to responsible freedom of access to the open countryside. Progress has been impressive - although there is still some way to go for the Government to deliver its commitment to improve access for responsible outdoor recreation. -

Alpine Adventures 2019 68

RYDER WALKER THE GLOBAL TREKKING SPECIALISTS ALPINE ADVENTURES 2019 68 50 RYDER WALKER ALPINE ADVENTURES CONTENTS 70 Be the first to know. Scan this code, or text HIKING to 22828 and receive our e-newsletter. We’ll send you special offers, new trip info, RW happenings and more. 2 RYDERWALKER.COM | 888.586.8365 CONTENTS 4 Celebrating 35 years of Outdoor Adventure 5 Meet Our Team 6 Change and the Elephant in the Room 8 Why Hiking is Important – Watching Nature 10 Choosing the Right Trip for You 11 RW Guide to Selecting Your Next Adventure 12 Inspired Cuisine 13 First Class Accommodations 14 Taking a Closer Look at Huts 15 Five Reasons Why You Should Book a Guided Trek 16 Self-Guided Travel 17 Guided Travel & Private Guided Travel EASY TO MODERATE HIKING 18 Highlights of Switzerland: Engadine, Lago Maggiore, Zermatt 20 England: The Cotswolds 22 Isola di Capri: The Jewel of Southern Italy NEW 24 French Alps, Tarentaise Mountains: Bourg Saint Maurice, Sainte Foy, Val d’Isère 26 Sedona, Arches & Canyonlands 28 Croatia: The Dalmatian Coast 28 30 Engadine Trek 32 Scotland: Rob Roy Way 34 Montenegro: From the Durmitor Mountain Range to the Bay of Kotor 36 New Mexico: Land of Enchantment, Santa Fe to Taos NEW 38 Slovakia: Discover the Remote High Tatras Mountains NEW MODERATE TO CHALLENGING HIKING 40 Heart of Austria 42 Italian Dolomites Trek 44 High Peaks of the Bavarian Tyrol NEW 46 Sicily: The Aeolian Islands 48 Rocky Mountain High Life: Aspen to Telluride 50 New Brunswick, Canada: Bay of Fundy 52 Via Ladinia: Italian Dolomites 54 Dolomiti di -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

Catalogue 48: June 2013

Top of the World Books Catalogue 48: June 2013 Mountaineering Fiction. The story of the struggles of a Swiss guide in the French Alps. Neate X134. Pete Schoening Collection – Part 1 Habeler, Peter. The Lonely Victory: Mount Everest ‘78. 1979 Simon & We are most pleased to offer a number of items from the collection of American Schuster, NY, 1st, 8vo, pp.224, 23 color & 50 bw photos, map, white/blue mountaineer Pete Schoening (1927-2004). Pete is best remembered in boards; bookplate Ex Libris Pete Schoening & his name in pencil, dj w/ edge mountaineering circles for performing ‘The Belay’ during the dramatic descent wear, vg-, cloth vg+. #9709, $25.- of K2 by the Third American Karakoram Expedition in 1953. Pete’s heroics The first oxygenless ascent of Everest in 1978 with Messner. This is the US saved six men. However, Pete had many other mountain adventures, before and edition of ‘Everest: Impossible Victory’. Neate H01, SB H01, Yak H06. after K2, including: numerous climbs with Fred Beckey (1948-49), Mount Herrligkoffer, Karl. Nanga Parbat: The Killer Mountain. 1954 Knopf, NY, Saugstad (1st ascent, 1951), Mount Augusta (1st ascent) and King Peak (2nd & 1st, 8vo, pp.xx, 263, viii, 56 bw photos, 6 maps, appendices, blue cloth; book- 3rd ascents, 1952), Gasherburm I/Hidden Peak (1st ascent, 1958), McKinley plate Ex Libris Pete Schoening, dj spine faded, edge wear, vg, cloth bookplate, (1960), Mount Vinson (1st ascent, 1966), Pamirs (1974), Aconcagua (1995), vg. #9744, $35.- Kilimanjaro (1995), Everest (1996), not to mention countless climbs in the Summarizes the early attempts on Nanga Parbat from Mummery in 1895 and Pacific Northwest. -

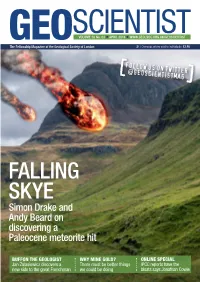

FALLING SKYE Simon Drake and Andy Beard on Discovering a Paleocene Meteorite Hit

SCIENTISTVOLUME 28 No. 03 ◆ APRIL 2018 ◆ WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST GEOThe Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 FOLLOW US ON TWITTER @GEOSCIENTISTMAG FALLING SKYE Simon Drake and Andy Beard on discovering a Paleocene meteorite hit BUFFON THE GEOLOGIST WHY MINE GOLD? ONLINE SPECIAL Jan Zalasiewicz discovers a There must be better things IPCC reports have the new side to the great Frenchman we could be doing bloats says Jonathan Cowie GE L DATES FOR YOUR DIARY PESGB GEOLiteracy TOUR 2018 LONDON The Chicxulub Tuesday 15 May, 18.00 Cavendish Conference Centre Public event Impact £15 @Barcroft The End of an Era BIRMINGHAM With Professor Joanna Morgan Wednesday 16 May, 17.30 Lyttelton Theatre, Professor of Geophysics, The Birmingham & Midland Department of Earth Science & Engineering, Institute Imperial College London Public event Free In 1980 Luis Alvarez and his co-workers published an article asserting that a large body hit Earth ~66 million years ago and caused the most recent mass extinction, which notably included ABERDEEN AD SPACEthe dinosaurs. Thursday 17 May, 18.00 The evidence for impact was the extraterrestrial composition Aberdeen Science Centre of a thin clay layer at the boundary between the Mesozoic and Cenozoic Eras. This became known as the “Impact hypothesis”, Public event and was categorically dismissed by many geologists at the time, £10 on the grounds that only two locations had been studied and the clay layer at these sites might be atypical or just unusual but terrestrial, and that the extinction was gradual and started NORTH WEST HIGHLANDS before the impactor hit Earth. -

Les Clochers D'arpette

31 Les Clochers d’Arpette Portrait : large épaule rocheuse, ou tout du moins rocailleuse, de 2814 m à son point culminant. On trouve plusieurs points cotés sur la carte nationale, dont certains sont plus significatifs que d’autres. Quelqu’un a fixé une grande branche à l’avant-sommet est. Nom : en référence aux nombreux gendarmes rocheux recouvrant la montagne sur le Val d’Arpette et faisant penser à des clochers. Le nom provient surtout de deux grosses tours très lisses à 2500 m environ dans le versant sud-est (celui du Val d’Arpette). Dangers : fortes pentes, chutes de pierres et rochers à « varapper » Région : VS (massif du Mont Blanc), district d’Entremont, commune d’Orsières, Combe de Barmay et Val d’Arpette Accès : Martigny Martigny-Combe Les Valettes Champex Arpette Géologie : granites du massif cristallin externe du Mont Blanc Difficulté : il existe plusieurs itinéraires possibles, partant aussi bien d’Arpette que du versant opposé, mais il s’agit à chaque fois d’itinéraires fastidieux et demandant un pied sûr. La voie la plus courte et relativement pas compliquée consiste à remonter les pentes d’éboulis du versant sud-sud-ouest et ensuite de suivre l’arête sud-ouest exposée (cotation officielle : entre F et PD). Histoire : montagne parcourue depuis longtemps, sans doute par des chasseurs. L’arête est fut ouverte officiellement par Paul Beaumont et les guides François Fournier et Joseph Fournier le 04.09.1891. Le versant nord fut descendu à ski par Cédric Arnold et Christophe Darbellay le 13.01.1993. Spécificité : montagne sauvage, bien visible de la région de Fully et de ses environs, et donc offrant un beau panorama sur le district de Martigny, entre autres… 52 32 L’Aiguille d’Orny Portrait : aiguille rocheuse de 3150 m d’altitude, dotée d’aucun symbole, mais équipée d’un relais d’escalade.