The Wine Industry in British Columbia: Issues and Potential

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents

German Red Wines – Steve Zins 11/12/2014 Final Rev 5.0 Contents • Introduction • German Wine - fun facts • German Geography • Area Classification • Wine Production • Trends • Permitted Reds • Wine Classification • Wine Tasting • References Introduction • Our first visit to Germany was in 2000 to see our daughter who was attending college in Berlin. We rented a car and made a big loop from Frankfurt -Koblenz / Rhine - Black forest / Castles – Munich – Berlin- Frankfurt. • After college she took a job with Honeywell, moved to Germany, got married, and eventually had our first grandchild. • When we visit we always try to visit some new vineyards. • I was surprised how many good red wines were available. So with the help of friends and family we procured and carried this collection over. German Wine - fun facts • 90% of German reds are consumed in Germany. • Very few wine retailers in America have any German red wines. • Most of the largest red producers are still too small to export to USA. • You can pay $$$ for a fine French red or drink German reds for the entire year. • As vineyard owners die they split the vineyards between siblings. Some vineyards get down to 3 rows. Siblings take turns picking the center row year to year. • High quality German Riesling does not come in a blue bottle! German Geography • Germany is 138,000 sq mi or 357,000 sq km • Germany is approximately the size of Montana ( 146,000 sq mi ) • Germany is divided with respect to wine production into the following: • 13 Regions • 39 Districts • 167 Collective vineyard -

May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NEWFOUNDLAND STUDIES TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED (Without Author' s Permission) p CLASS ACTS: CULINARY TOURISM IN NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR by Holly Jeannine Everett A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Folklore Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2005 St. John's Newfoundland ii Class Acts: Culinary Tourism in Newfoundland and Labrador Abstract This thesis, building on the conceptual framework outlined by folklorist Lucy Long, examines culinary tourism in the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. The data upon which the analysis rests was collected through participant observation as well as qualitative interviews and surveys. The first chapter consists of a brief overview of traditional foodways in Newfoundland and Labrador, as well as a summary of the current state of the tourism industry. As well, the methodology which underpins the study is presented. Chapter two examines the historical origins of culinary tourism and the development of the idea in the Canadian context. The chapter ends with a description of Newfoundland and Labrador's current culinary marketing campaign, "A Taste of Newfoundland and Labrador." With particular attention to folklore scholarship, the course of academic attention to foodways and tourism, both separately and in tandem, is documented in chapter three. The second part of the thesis consists of three case studies. Chapter four examines the uses of seal flipper pie in hegemonic discourse about the province and its culture. Fried foods, specifically fried fish, potatoes and cod tongues, provide the starting point for a discussion of changing attitudes toward food, health and the obligations of citizenry in chapter five. -

Viticulture Research and Outreach Addressing the Ohio Grape and Wine Industry Production Challenges

HCS Series Number 853 ANNUAL OGIC REPORT (1 July ’16 – 30 June ‘17) Viticulture Research and Outreach Addressing the Ohio Grape and Wine Industry Production Challenges Imed Dami, Professor & Viticulture State Specialist Diane Kinney, Research Assistant II VITICULTURE PROGRAM Department of Horticulture and Crop Science 1 Table of Contents Page Executive Summary……………………………………………………………………………………………………..………….3 2016 Weather………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……..5 Viticulture Research……………………………………………………………………………………………………….…… 10 Project #1: Trunk Renewal Methods for Vine Recovery After Winter Injury……………………………………… 11 Project #2: Evaluation of Performance and Cultural Practices of Promising Wine Grape Varieties….. 16 Viticulture Production…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….28 Commercial Expansion of Varieties New to Ohio………………………………………………………………………………….28 Viticulture Extension & Outreach……………………………………………………………………………………………41 OGEN and Fruit Maturity Updates………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 41 Ohio Grape & Wine Conference………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 42 Industry Field Day and Workshops………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 43 “Buckeye Appellation” Website………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 45 Industry Meetings………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 45 Professional Meetings…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 45 Student Training & Accomplishments…………………………………………………………………………………… 49 Honors & Awards………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 50 Appendix………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. -

Genetic Structure and Domestication History of the Grape

Genetic structure and domestication history of the grape Sean Mylesa,b,c,d,1, Adam R. Boykob, Christopher L. Owense, Patrick J. Browna, Fabrizio Grassif, Mallikarjuna K. Aradhyag, Bernard Prinsg, Andy Reynoldsb, Jer-Ming Chiah, Doreen Wareh,i, Carlos D. Bustamanteb, and Edward S. Bucklera,i aInstitute for Genomic Diversity, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853; bDepartment of Genetics, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305; cDepartment of Biology, Acadia University, Wolfville, NS, Canada B4P 2R6; dDepartment of Plant and Animal Sciences, Nova Scotia Agricultural College, Truro, NS, Canada B2N 5E3; eGrape Genetics Research Unit, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cornell University, Geneva, NY 14456; fBotanical Garden, Department of Biology, University of Milan, 20133 Milan, Italy; gNational Clonal Germplasm Repository, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, University of California, Davis, CA 95616; hCold Spring Harbor Laboratory, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cold Spring Harbor, NY 11724; and iRobert W. Holley Center for Agriculture and Health, United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY14853 Edited* by Barbara A. Schaal, Washington University, St. Louis, MO, and approved December 9, 2010 (received for review July 1, 2010) The grape is one of the earliest domesticated fruit crops and, since sociations using linkage mapping. Because of the grape’s long antiquity, it has been widely cultivated and prized for its fruit and generation time (generally 3 y), however, establishing and wine. Here, we characterize genome-wide patterns of genetic maintaining linkage-mapping populations is time-consuming and variation in over 1,000 samples of the domesticated grape, Vitis expensive. -

Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada

MARKET INDICATOR REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2013 Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada Source: Planet Retail, 2012. Consumer Trends Wine, Beer and Spirits in Canada EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INSIDE THIS ISSUE Canada’s population, estimated at nearly 34.9 million in 2012, Executive Summary 2 has been gradually increasing and is expected to continue doing so in the near-term. Statistics Canada’s medium-growth estimate for Canada’s population in 2016 is nearly 36.5 million, Market Trends 3 with a medium-growth estimate for 2031 of almost 42.1 million. The number of households is also forecast to grow, while the Wine 4 unemployment rate will decrease. These factors are expected to boost the Canadian economy and benefit the C$36.8 billion alcoholic drink market. From 2011 to 2016, Canada’s economy Beer 8 is expected to continue growing with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) between 2% and 3% (Euromonitor, 2012). Spirits 11 Canada’s provinces and territories vary significantly in geographic size and population, with Ontario being the largest 15 alcoholic beverages market in Canada. Provincial governments Distribution Channels determine the legal drinking age, which varies from 18 to 19 years of age, depending on the province or territory. Alcoholic New Product Launch 16 beverages must be distributed and sold through provincial liquor Analysis control boards, with some exceptions, such as in British Columbia (B.C.), Alberta and Quebec (AAFC, 2012). New Product Examples 17 Nationally, value sales of alcoholic drinks did well in 2011, with by Trend 4% growth, due to price increases and premium products such as wine, craft beer and certain types of spirits. -

Determining the Classification of Vine Varieties Has Become Difficult to Understand Because of the Large Whereas Article 31

31 . 12 . 81 Official Journal of the European Communities No L 381 / 1 I (Acts whose publication is obligatory) COMMISSION REGULATION ( EEC) No 3800/81 of 16 December 1981 determining the classification of vine varieties THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, Whereas Commission Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/ 70 ( 4), as last amended by Regulation ( EEC) No 591 /80 ( 5), sets out the classification of vine varieties ; Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Economic Community, Whereas the classification of vine varieties should be substantially altered for a large number of administrative units, on the basis of experience and of studies concerning suitability for cultivation; . Having regard to Council Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 of 5 February 1979 on the common organization of the Whereas the provisions of Regulation ( EEC) market in wine C1), as last amended by Regulation No 2005/70 have been amended several times since its ( EEC) No 3577/81 ( 2), and in particular Article 31 ( 4) thereof, adoption ; whereas the wording of the said Regulation has become difficult to understand because of the large number of amendments ; whereas account must be taken of the consolidation of Regulations ( EEC) No Whereas Article 31 of Regulation ( EEC) No 337/79 816/70 ( 6) and ( EEC) No 1388/70 ( 7) in Regulations provides for the classification of vine varieties approved ( EEC) No 337/79 and ( EEC) No 347/79 ; whereas, in for cultivation in the Community ; whereas those vine view of this situation, Regulation ( EEC) No 2005/70 varieties -

Canadian Blended Wine Industry and Labelling Overview January 2017 There Are Two Types of Wines Primarily Produced in Canada

Canadian Blended Wine Industry and Labelling Overview January 2017 There are two types of wines primarily produced in Canada: 100% Canadian (includes VQA and BC VQA) and International Canadian Blends. Together, they contribute an annual economic impact of $6.8 billion ($3.7B for 100% Canadian and $3.1B for blended wines). Blended wines are an important part of the Canadian wine industry, supporting over 10,000 jobs (direct and indirect) and purchasing more than 15,000 tonnes of Canadian grapes annually. International Canadian Blended (ICB) wines use the label “Cellared in Canada by (naming the company), (address) from imported and/or domestic wines” label designation must include domestic content to meet federal labelling requirements to ensure the label is not false, misleading or deceptive. Ontario regulations require that blended wines produced and sold in the province, contain a minimum 25% Ontario grape content. ICB wines are sold domestically to compete against imported wines in the value price category. For example, the LCBO reports that the average price of an ICB wine is $7.54, compared $13.25 for a VQA wine and $31.56 for a VQA wine in its specialty section, VINTAGES. Canada has a long history of blending domestic and imported wines. We are not unique, as blended wines are produced around the world, including major wine producing countries like Europe and the United States. Labelling of Wine in Canada Canada’s Food and Drug Act Regulations require wine labels to include “a clear indication of the country of origin,” while beer, spirits and all other food products can voluntarily indicate country of origin on the label. -

Regulatory and Institutional Developments in the Ontario Wine and Grape Industry

International Journal of Wine Research Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article OrigiNAL RESEARCH Regulatory and institutional developments in the Ontario wine and grape industry Richard Carew1 Abstract: The Ontario wine industry has undergone major transformative changes over the last Wojciech J Florkowski2 two decades. These have corresponded to the implementation period of the Ontario Vintners Quality Alliance (VQA) Act in 1999 and the launch of the Winery Strategic Plan, “Poised for 1Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Pacific Agri-Food Research Greatness,” in 2002. While the Ontario wine regions have gained significant recognition in Centre, Summerland, BC, Canada; the production of premium quality wines, the industry is still dominated by a few large wine 2Department of Agricultural and Applied Economics, University of companies that produce the bulk of blended or “International Canadian Blends” (ICB), and Georgia, Griffin, GA, USA multiple small/mid-sized firms that produce principally VQA wines. This paper analyzes how winery regulations, industry changes, institutions, and innovation have impacted the domestic production, consumption, and international trade, of premium quality wines. The results of the For personal use only. study highlight the regional economic impact of the wine industry in the Niagara region, the success of small/mid-sized boutique wineries producing premium quality wines for the domestic market, and the physical challenges required to improve domestic VQA wine retail distribution and bolster the international trade of wine exports. Domestic success has been attributed to the combination of natural endowments, entrepreneurial talent, established quality standards, and the adoption of improved viticulture practices. -

Media Kit the Wines of British Columbia “Your Wines Are the Wines of Sensational!” British Columbia ~ Steven Spurrier

MEDIA KIT THE WINES OF BRITISH COLUMBIA “YOUR WINES ARE THE WINES OF SENSATIONAL!” BRITISH COLUMBIA ~ STEVEN SPURRIER British Columbia is a very special place for wine and, thanks to a handful of hard-working visionaries, our vibrant industry has been making a name for itself nationally and internationally for the past 25 years. “BC WINE OFTEN HAS In 1990, the Vintner’s Quality Alliance (VQA) standard was created to guarantee consumers they A RADICAL FRESHNESS were drinking wine made from 100% BC grown grapes. Today, BC VQA Wines dominate wine sales AND A REMARKABLE in British Columbia, and our wines are finding their way to more places than ever before, winning ABILITY TO DEFY over both critics and consumers internationally. THE CONVENTIONAL CATEGORIES OF TASTE.” The Wines of British Columbia truly are a reflection of the land where the grapes are grown and the exceptional people who craft them. We invite you to join us to savour all that makes the Wines of STUART PIGOTT British Columbia so special. ~ “WHAT I LOVE MOST ABOUT BC WINES IS THEY MIMIC THE PLACE, THEY MIMIC THE PURITY. YOU LOOK OUT AND FEEL THE AIR, TASTE THE WATER AND LOOK AT THE LAKE AND YOU CAN’T HELP BUT BE STRUCK BY A SENSE OF PURITY AND IT CARRIES OVER TO THE WINE. THEY HAVE PURITY AND A SENSE OF WEIGHTLESSNESS WHICH IS VERY ETHEREAL AND CAPTIVATING.” ~ KAREN MACNEIL DID YOU KNOW? • British Columbia’s Vintners Quality Alliance (BC VQA) designation celebrated 25 years of excellence in 2015. • BC’s Wine Industry has grown from just 17 grape wineries in 1990 to more than 275 today (as of January 2017). -

Cheryl Lawrence Liquor Agency Ltd

Cheryl Lawrence Liquor Agency Ltd. Blasted Church Vineyards Chaberton Estate Winery Elephant Island Orchard Wines Fairview Cellars Gehringer Brothers Estate Winery Lang Vineyards Meyer Family Vineyards Mt Boucherie Estate Winery Naramata Cider Co. Rust Wine Co. St Hubertus Estate Winery Summerhill Pyramid Winery Tinhorn Creek Vineyards Blasted Church Hatfield’s Fuse 2017 VQA+734475 LRS $14.41 / LIC $17.99 *By the Glass $13.99 *27% Pinot Gris, 12% Pinot Blanc, 12% Ehrenfelser, 10% Gewurztraminer, 9% Viognier, 9 % Optima, 5% Chardonnay Musque, 4% Chardonnay, 3% Orange Muscat, 3% Sauvignon Blanc, 3% Pinot Noir & 3% Riesling Once again, the 2016 Hatfield’s Fuse is a cornucopia of flavours made with twelve different grape varieties. Aromas of melon, mango, pineapple, and tangerine with a hint of citrus complement the apple and pear flavours. The mouth- filling fruit ripeness carries through to the long, slightly sweet finish. This versatile white blend is the perfect match for halibut or cod whether drizzled with herb butter or battered, fried and salted. Also try with butter chicken, mild curries, pad Thai or drunken crab. 13.0% Bouquet: Melon, mango, pineapple, and tangerine with a hint of citrus. Palate: Tropical fruit salad along with apple and pear. Mouth filling fruit ripeness carries through to the lovely, long, slightly sweet finish. Food Pairings: Halibut or cod drizzled with herb butter or battered, fried and salted. SILVER BC Lieutenant Governor’s Wine Awards Okanagan Wine Festival 2018 Blasted Church Gewurztraminer 2017 VQA+711200 LRS $13.77 / LIC $17.49 This beautifully balanced wine is 100% estate grown. Classic rose petal, blossom and lychee notes introduce the wine, followed by spice, orange and lime. -

2010 British Columbia Wine Awards

2010 British Columbia Wine Awards www.thewinefestivals.com or access our site from your mobile www.owfs.mobi Follow Us: twitter.com/OKWineFests • facebook.com/OKWFS G o o d T hi ng s come in Rich ard G s o Pa o e in R ck d om ich a G T c a g o hings rd in o s g d T h i ng s c ome in Richards Pa ck ag in g SERVING THE WINE INDUSTRY SINCE 1990 WE CARRY NORTH AMERICAN GLASSWARE AS WELL AS THE EVER POPULAR ASIAN LINE RICHARDS PACKAGING INC. NO PROBLEMS......ONLY SOLUTIONS TO YOUR PACKAGING NEEDS COLETTA MCKINNEY - ACCOUNT MANAGER PH: (604) 270-0111 FAX: (604) 270-8937 CELL: (250) 878-8441 E-MAIL: [email protected] JOSH PARIS - ACCOUNT MANAGER (WASHINGTON) CELL: 1-206-465-7032 E-MAIL: [email protected] VISIT US WWW.RICHARDSPACKAGING.COM GOLD MEDAL WINNERS WINERY BRAND NAME VINTAGE Arrowleaf Cellars First Crush Rose 2009 Blasted Church Vineyards Chardonnay Musque 2009 Cassini Cellars Pinot Noir Reserve 2007 CedarCreek Estate Winery Pinot Noir 2008 Church & State Wines Hollenbach Pinot Noir 2007 Desert Hills Estate winery Syrah Select 2007 Domaine de Chaberton Estate Winery Siegerrebe 2008 Hester Creek Estate Winery Reserve Cabernet Franc 2007 Inniskillin Okanagan Dark Horse Vineyard Riesling Icewine 2008 Intrigue Wines Riesling 2009 Jackson-Triggs Okanagan Estate Proprietors’ Reserve Dry Riesling 2008 Jackson-Triggs Okanagan Estate Grand Reserve Riesling 2008 Jackson-Triggs Okanagan Estate Grand Reserve Merlot 2007 Jackson-Triggs Okanagan Estate Proprietors’ Reserve Shiraz 2007 Jackson-Triggs Okanagan Estate Grand Reserve -

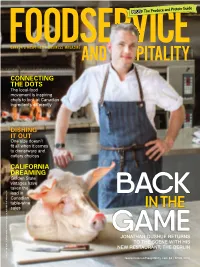

Connecting the Dots

CONNECTING THE DOTS The local-food movement is inspiring chefs to look at Canadian ingredients differently DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit all when it comes to dinnerware and cutlery choices CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden State vintages have taken the lead in Canadian table-wine sales JONATHAN GUSHUE RETURNS TO THE SCENE WITH HIS NEW RESTAURANT, THE BERLIN CANADIAN PUBLICATION MAIL PRODUCT SALES AGREEMENT #40063470 CANADIAN PUBLICATION foodserviceandhospitality.com $4 | APRIL 2016 VOLUME 49, NUMBER 2 APRIL 2016 CONTENTS 40 27 14 Features 11 FACE TIME Whether it’s eco-proteins 14 CONNECTING THE DOTS The 35 CALIFORNIA DREAMING Golden or smart technology, the NRA Show local-food movement is inspiring State vintages have taken the lead aims to connect operators on a chefs to look at Canadian in Canadian table-wine sales host of industry issues ingredients differently By Danielle Schalk By Jackie Sloat-Spencer By Andrew Coppolino 37 DISHING IT OUT One size doesn’t fit 22 BACK IN THE GAME After vanish - all when it comes to dinnerware and ing from the restaurant scene in cutlery choices By Denise Deveau 2012, Jonathan Gushue is back CUE] in the spotlight with his new c restaurant, The Berlin DEPARTMENTS By Andrew Coppolino 27 THE SUSTAINABILITY PARADIGM 2 FROM THE EDITOR While the day-to-day business of 5 FYI running a sustainable food operation 12 FROM THE DESK is challenging, it is becoming the new OF ROBERT CARTER normal By Cinda Chavich 40 CHEF’S CORNER: Neil McCue, Whitehall, Calgary PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY [NEIL M OF ACADIA], COLIN WAY PHOTOS: CINDY LA [TASTE FOODSERVICEANDHOSPITALITY.COM FOODSERVICE AND HOSPITALITY APRIL 2016 1 FROM THE EDITOR For daily news and announcements: @foodservicemag on Twitter and Foodservice and Hospitality on Facebook.