Climate Vulnerability Risk Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Insights Into the Microbiota of Moth Pests

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review New Insights into the Microbiota of Moth Pests Valeria Mereghetti, Bessem Chouaia and Matteo Montagna * ID Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie e Ambientali, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (B.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5031-6782 Received: 31 August 2017; Accepted: 14 November 2017; Published: 18 November 2017 Abstract: In recent years, next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have helped to improve our understanding of the bacterial communities associated with insects, shedding light on their wide taxonomic and functional diversity. To date, little is known about the microbiota of lepidopterans, which includes some of the most damaging agricultural and forest pests worldwide. Studying their microbiota could help us better understand their ecology and offer insights into developing new pest control strategies. In this paper, we review the literature pertaining to the microbiota of lepidopterans with a focus on pests, and highlight potential recurrent patterns regarding microbiota structure and composition. Keywords: symbiosis; bacterial communities; crop pests; forest pests; Lepidoptera; next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies; diet; developmental stages 1. Introduction Insects represent the most successful taxa of eukaryotic life, being able to colonize almost all environments, including Antarctica, which is populated by some species of chironomids (e.g., Belgica antarctica, Eretmoptera murphyi, and Parochlus steinenii)[1,2]. Many insects are beneficial to plants, playing important roles in seed dispersal, pollination, and plant defense (by feeding upon herbivores, for example) [3]. On the other hand, there are also damaging insects that feed on crops, forest and ornamental plants, or stored products, and, for these reasons, are they considered pests. -

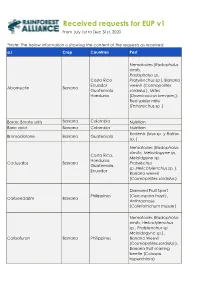

IIS 2020 Requests Overview

Received requests for EUP v1 From July 1st to Dec 31st, 2020 *Note: The below information is showing the content of the requests as received. a.i Crop Countries Pest Nematodes ( Radophulus similis, Radopholus sp, Costa Rica Pratylenchus sp ), Banana Ecuador weevil ( Cosmopolites Abamectin Banana Guatemala sordidus ), Mites Honduras (Dysmicoccus brevipes ), Red spider mite (Tetranychus sp .) Borax; Borate salts Banana Colombia Nutrition Boric acid Banana Colombia Nutrition Rodents ( Mus sp. y Rattus Bromadiolone Banana Guatemala sp. ) Nematodes ( Radopholus silmillis, Meloidogyne sp, Costa Rica, Meloidgune sp, Honduras, Cadusafos Banana Pratylechus Guatemala, sp.,Helicotylenchus sp. ), Ecuador Banana weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus ) Diamond Fruit Sport Philippines (Cercospora hayii ), Carbendazim Banana Anthracnose (Colletotrichum musae ) Nematod es (Radopholus similis, Helicotylenchus sp., Pratylenchus sp. Meloidogyne sp.) , Carbofuran Banana Philippines Banana Weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus ), Banana fruit scarring beetle (Colaspis hyperchlora) a.i Crop Countries Pest Black Sigatoka Ecuador, Costa (Mycosphaerella fijiensis ), Rica, Philippines, Yellow Sigatoka Chlorothalonil Banana Honduras, (Mycosphaerella Guatemala, musicola ), Banana Colombia Freckle ( Phyllosticta musarum ) Mealybug ( Dysmicoccus brevipes, Pseudococcus elisae, Pseudococcus sp, Ferrista sp ), Dysmicoccus sp , Scale insects (Aspidiotus destructor, Diaspis boisduvalii ), Thrips (Thrips florum, Franckliniella spp, Chaetanaphothrips signipennis ), Banana fruit Philippines, -

The Effects of Climate Change on the Pests and Diseases of Coffee

y & W log ea to th a e im r l F o Journal of Climatology & Weather C f r e o c l a a s n Groenen, Climatol Weather Forecasting 2018, 6:3 t r i n u g o J Forecasting DOI: 10.4172/2332-2594.1000239 ISSN: 2332-2594 Review Article Open Access The Effects of Climate Change on the Pests and Diseases of Coffee Crops in Mesoamerica Danielle Groenen* Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science and Center for Ocean–Atmospheric Prediction Studies, Florida State University, Florida, United States *Corresponding author: Danielle Groenen, Department of Earth, Ocean and Atmospheric Science and Center for Ocean–Atmospheric Prediction Studies, Florida State University, Florida, United States, Tel: 18506442525; E-mail: [email protected] Received Date: August 30, 2018; Accepted Date: September 21, 2018; Published Date: September 26, 2018 Copyright: © 2018 Groenen D. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Coffee is an in-demand commodity that is being threatened by climate change. Increasing temperatures and rainfall variability are predicted in the region of Mexico and Central America (Mesoamerica). This region is plagued with pests and diseases that have already caused millions of dollars in damages and losses to the coffee industry. This paper examines three pests that negatively affect coffee plants: the coffee borer beetle, the black twig borer, and nematodes. In addition, this paper examines three diseases that can destroy coffee crops: bacterial blight, coffee berry disease, and coffee leaf rust. -

Coffee Plant the Coffee Plant Makes a Great Indoor, Outdoor Shade, Or Office Plant

Coffee Plant The coffee plant makes a great indoor, outdoor shade, or office plant. Water when dry or the plant will let you know when it droops. Do not let it sit in water so tip over the pot if you over water the plant. Preform the finger test to check for dryness. When the plant is dry about an inch down, water thoroughly. The plant will stay pot bound about two years at which time you will transplant and enjoy a beautiful ornamental plant. See below. Coffea From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia This article is about the biology of coffee. For the beverage, see Coffee. Coffea Coffea arabica trees in Brazil Scientific classification Kingdom: Plantae (unranked): Angiosperms (unranked): Eudicots (unranked): Asterids Order: Gentianales Family: Rubiaceae Subfamily: Ixoroideae Tribe: Coffeeae[1] Genus: Coffea L. Type species Coffea arabica L.[2] Species Coffea ambongensis Coffea anthonyi Coffea arabica - Arabica Coffee Coffea benghalensis - Bengal coffee Coffea boinensis Coffea bonnieri Coffea canephora - Robusta coffee Coffea charrieriana - Cameroonian coffee - caffeine free Coffea congensis - Congo coffee Coffea dewevrei - Excelsa coffee Coffea excelsa - Liberian coffee Coffea gallienii Coffea liberica - Liberian coffee Coffea magnistipula Coffea mogeneti Coffea stenophylla - Sierra Leonian coffee Coffea canephora green beans on a tree in Goa, India. Coffea is a large genus (containing more than 90 species)[3] of flowering plants in the madder family, Rubiaceae. They are shrubs or small trees, native to subtropical Africa and southern Asia. Seeds of several species are the source of the popular beverage coffee. After their outer hull is removed, the seeds are commonly called "beans". -

Wo 2011/022435 A2

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date 24 February 2011 (24.02.2011) WO 2011/022435 A2 (51) International Patent Classification: AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, AOlN 63/00 (2006.01) CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, (21) International Application Number: HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, PCT/US2010/045808 KR, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, (22) International Filing Date: ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, 17 August 2010 (17.08.2010) NO, NZ, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, RO, RS, RU, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (25) Filing Language: English TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (26) Publication Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (30) Priority Data: kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, 61/234,6 13 17 August 2009 (17.08.2009) US GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, SD, SL, SZ, TZ, UG, 61/300,402 1 February 2010 (01 .02.2010) US ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, MD, RU, TJ, 61/303,288 10 February 2010 (10.02.2010) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, (72) Inventor; and LV, MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, SE, SI, SK, (71) Applicant : DE CRECY, Eudes [FR/US]; 6716 Sw 100 SM, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, Lane, Gainesville, FL 32608 (US). -

Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia

Republic of Colombia PCC COFFEE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE PAISAJE CULTURAL CAFETERO- Management Plan Unofficial Translation Coordinating Committee: Ministry of Culture Colombian Coffee Growers’ Federation Bogotá, September 2009 1 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 5 2. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE COFFEE CULTURE LANDSCAPE 2.1. DESCRIPTION ........................................................................ 2.1.1. The human, family centered, generational, and historical efforts related to the production of quality coffee, within a framework of sustainable human development ................................................................... 11 2.1.2. Coffee culture for the world ......................................... 16 2.1.3. Strategic social capital built around its coffee growing institutions 29 2.1.4.The relationship between tradition and technology: Guaranteeing the quality and sustainability of a product 34 2.1 2.2. THE PCC’S CURRENT STATE OF CONSERVATION 2.2.1.The human, family centered, generational, and historical efforts related to the production of quality coffee, within a framework of sustainable human development 2.2.2.Coffee culture for the world 2.2.3.Strategic social capital built around coffee growing institutions 51 2 2 2.2.4.The relationship between tradition and technology: Guaranteeing product quality and sustainability 53 2.3. FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE PCC ............................................... 56 2.3.1.Developmental pressures 2.3.2. Environmental pressures -

What Are the Iscs?

ISCs Invasive Species Committees of Hawai‘i What are the ISCs? Successes Challenges Island Overviews Education & Outreach Where the ISCs work Preserving Hawaiian Culture The Power of Partnerships Why Invasive Species Matter Funding Outlook 2015 The ISCs are projects of the University of Hawaiʽi's Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit What are the Invasive Species Committees? awaiʻi's Invasive Species None of the ISCs has corporate or non- Committees operate on profit status. The "business side" of H the ISCs (accounting, audits, payroll, five islands, targeting invasive workmen’s compensation, and grant species on a landscape level. management) is primarily managed by the Pacific Cooperative Studies Unit (PCSU), an applied-research unit of the University The ISCs were created to facilitate and of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. The ISCs are entirely streamline invasive species control work funded by grants and donations. that existing state and federal agencies had difficulties addressing. The ISCs are The hired manager and staff of each ISC informal, inter-agency partnerships working develop action plans and carry out all to identify and eradicate some of the most survey and control work. Each ISC has a threatening incipient pests. The formation robust outreach program to educate and of these partnerships began on Maui in engage the public. Species targeted for 1991 directed toward controlling Miconia control are both ecological and incipient calvescens, a highly invasive melastome tree agricultural pests and include plants, from Central and South America that had vertebrates, insects and pathogens. ISC devastated Tahiti's forests and threatened to work is scientifically grounded, "data- do the same if left unchallenged in Hawaiʻi. -

Coffea Arabica

COFFEA ARABICA A MONOGRAPH 1 COFFEA ARABICA A MONOGRAPH Catalina Casasbuenas Agricultural Science 2016-17 Colegio Bolivar 2017 Table of Contents Introduction 2 ORIGIN AND DISTRIBUTION 2 1.1 Origin 2 1.2 Affinities and taxonomy 3 ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS AFFECTING DISTRIBUTION 3 2.1 Biology. 3 2.2 Cultivation. 3 2.2 Rainfall 4 2.3 Elevation 4 2.4 Climate 5 2.5 Pests and diseases 5 3. BIOLOGY 9 3.1 Chromosome complement. 9 3.2 Life cycle and phenology 10 3.2.1 Life cycle and longevity 10 3.2.2 Flowering and fruit seasonality10 3.2.3 Flowering and fruiting frequency. 11 3.3 Reproductive biology 11 3.3.1 Pollen 11 3.3.3 Pollination and potential pollinators 12 3.3.4 Fruit development and seed potential 12 4. Propagation and Management 13 4.1 Natural regeneration 13 4.2 Nursery propagation 13 4.2.1 Propagation from seed 13 5. Vegetative propagation 14 5.1 Grafting 14 5.2 Cuttings 15 5.3 Planting 15 6. Management 16 6.1 Flowering 16 6.2 Tending 16 6.2.1 Pest and disease control 17 7. Emerging products, potential markets. 22 7.1. The overall picture 22 7.2 Potential markets 23 7.2.1 Coffee bean exports and produces. 23 7.3 Food items based on coffee bean 23 7.3.1 Brewed coffee 23 8. Medicinal and traditional uses 24 8.1 Medicinal uses and effectiveness 24 8.2.1 Type 2 Diabetes 25 8.2.2 Parkinson’s disease 25 8.2.3 Gallstones 26 8.2.4 Colorectal cancer 26 8.2.5 Health benefits 26 Bibliography 27 INTRODUCTION Coffea arabica, native of Ethiopia, is known to be as one of the most important crops worldwide. -

Landscape Processes Underpinning Bird Persistence and Avian-Mediated Pest Control in Fragmented Landscapes

Andrea Larissa Boesing Landscape processes underpinning bird persistence and avian-mediated pest control in fragmented landscapes São Paulo 2016 Andrea Larissa Boesing Landscape processes underpinning bird persistence and avian-mediated pest control in fragmented landscapes Persistência de aves e controle de pragas em paisagens fragmentadas – uma perspectiva da ecologia de paisagens Tese apresentada ao Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo, para a obtenção de Título de Doutor em Ciências, na Área de Ecologia. Orientador: Jean Paul Metzger Co-orientadora: Elizabeth Nichols São Paulo 2016 FichaCatalográfica Boesing, Andrea Larissa Persistência de aves e controle de pragas em paisagens fragmentadas – uma perspectiva da ecologia de paisagens 181 páginas Tese (Doutorado) - Instituto de Biociências da Universidade de São Paulo. Departamento de Ecologia. 1.Estrutura da paisagem 2.Cobertura florestal 3.Mata Atlântica Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Biociências. Departamento de Ecologia. Comissão Julgadora: Prof(a). Dr(a). Prof(a). Dr(a). Prof(a). Dr(a). Prof(a). Dr(a). Prof. Dr. Jean Paul Metzger Orientador(a) Dedication Dedico... “Àquela que sempre motivou a busca dos sonhos mais ousados, Que me ensinou a soltar as amarras, Que me mostrou como ser forte e nunca desistir. A você, meu exemplo de mulher e sabedoria, Que acompanhou o começo da jornada, mas infelizmente não o fim...” Cila Friedrich Boesing (In memorian) Epigraph Hold fast to dreams For if dreams die Life is a broken-winged bird That cannot fly. Hold fast to dreams For when dreams go Life is a barren field Frozen with snow. Langston Hughes Acknowledgments Este trabalho é resultado de um esforço conjunto que envolveu muitas pessoas. -

Salmo De Melo Daví Júnior Resistance of Insecticide

SALMO DE MELO DAVÍ JÚNIOR RESISTANCE OF INSECTICIDE-TREATED COFFEE BERRIES OF DIFFERENT VARIETIES TO THE PENETRATION OF Hypothenemus hampei (COLEOPTERA: CURCULIONIDAE: SCOLYTINAE) Dissertation presented to the Federal University of Uberlândia, as part of the requirements of the Graduate Program in Agronomy - Master's Degree, to obtain the title of "Master". Supervisor Prof. Dr. Flávio Lemes Fernandes UBERLÂNDIA MINAS GERAIS - BRAZIL 2020 SALMO DE MELO DAVÍ JÚNIOR RESISTANCE OF INSECTICIDE-TREATED COFFEE BERRIES OF DIFFERENT VARIETIES TO THE PENETRATION OF Hypothenemus hampei (COLEOPTERA: CURCULIONIDAE: SCOLYTINAE) Dissertation presented to the Federal University of Uberlândia, as part of the requirements of the Graduate Program in Agronomy - Master's Degree, to obtain the title of "Master". Aprroved in February 19th, 2020. Prof.a Dra. Vanessa Andalo Mendes de Carvalho Prof. Dr. Marcus Vinícius Sampaio Prof. Dr. Ézio Marques da Silva Prof. Dr Flávio Lemes Fernandes (Supervisor) UBERLÂNDIA MINAS GERAIS - BRAZIL 2020 02/03/2020 SEI/UFU - 1838014 - Ata de Defesa - Pós-Graduação UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE UBERLÂNDIA Secretaria do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Agronomia Rodovia BR 050, Km 78, Bloco 1CCG, Sala 206 - Bairro Glória, Uberlândia-MG, CEP 38400-902 Telefone: (34) 2512-6715/6716 - www.ppga.iciag.ufu.br - [email protected] ATA DE DEFESA - PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO Programa de Pós-Graduação Agronomia em: Defesa de: Dissertação de Mestrado Acadêmico, 009/2020 PPGAGRO Dezenove de fevereiro de Hora de Data: Hora de início: 08:00 12:30 dois mil e vinte encerramento: -

Genome of the Small Hive Beetle (Aethina Tumida, 2004;32(5):1792–7

GigaScience, 7, 2018, 1–16 doi: 10.1093/gigascience/giy138 Advance Access Publication Date: 7 December 2018 Research RESEARCH Genome of the small hive beetle (Aethina tumida, Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), a worldwide parasite of social bee colonies, provides insights into detoxification and herbivory Jay D. Evans 1,*, Duane McKenna2,ErinScully3, Steven C. Cook1, Benjamin Dainat, 4, Noble Egekwu1, Nathaniel Grubbs5, Dawn Lopez1, Marce´ D. Lorenzen5,StevenM.Reyna5, Frank D. Rinkevich6, Peter Neumann7 and Qiang Huang7,8,* 1USDA-ARS, Bee Research Laboratory, BARC-East Building 306, Beltsville, Maryland 20705, USA, 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Memphis, 3700 Walker Ave., Memphis, TN 38152, USA, 3USDA-ARS, Center for Grain and Animal Health, Stored Product Insect and Engineering Research Unit, Manhattan, KS 66502, USA, 4Agroscope, Swiss Bee Research Center, CH-3003 Bern, Switzerland, 5Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University, 1566 Thomas Hall, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA, 6USDA, Honey Bee Breeding, Genetics and Physiology Laboratory, 1157 Ben Hur Road, Baton Rouge, LA 70820, USA, 7Institute of Bee Health, Vetsuisse Faculty, University of Bern, Schwarzenburgstrasse 161, CH-3097, Liebefeld, Switzerland and 8Honey Bee Research Institute, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Zhimin Avenue 1101, 330045 Nanchang, China | downloaded: 10.10.2021 ∗Correspondence address. Jay D. Evans, USDA-ARS, Bee Research Laboratory, BARC-East Building 306, Beltsville, Maryland 20705, USA. E-mail: [email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0036-4651; Qiang Huang, E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Background: The small hive beetle (Aethina tumida; ATUMI) is an invasive parasite of bee colonies. ATUMI feeds on both fruits and bee nest products, facilitating its spread and increasing its impact on honey bees and other pollinators. -

Coffeesciencev11n2.Pdf

148 EFFECT OF LIGHT AND TEMPERATURE ON Cercospora coffeicolaSilva, M. AND G. da et al. Coffea arabica PATHOSYSTEM Marília Goulart da Silva1, Edson Ampélio Pozza2, Fernando Pereira Monteiro3, Caio Vítor Rodrigues Vaz de Lima4 (Recebido: 08 de junho de 2015; aceito: 09 de novembro de 2015) ABSTRACT: The mycelial growth rate (MGR), in vitro production of cercosporin, and intensity (incidence and severity) of Cercospora leaf spot on coffee seedlings ‘Catuaí Vermelho IAC 144’ were evaluated under different light intensities (80, 160, 240, and 320 µmol m-2 s-1) and temperatures (17, 21, 25, and 29°C). Dark condition (0 µmol m-2 s-1) was also included in in vitro experiments. In vivo, were evaluated incidence, severity, rates of chlorophyll a, b, and total in healthy (without symptoms) and sick tissues (with symptoms), and the photosynthetic rate and variables affecting it, were also evaluated. All the experiments were done at least two times. In in vitro experiments, the highest mycelial growth rate (MGR) was observed at 24.1°C in the dark condition (0 μmol m-2 s-1), while the highest amount of toxin occurred at 24.9°C and light intensity 320 μmol m-2 s-1. When dishes were incubated in the dark, the lowest levels of cercosporin were produced by the pathogen, regardless of temperature, thus confirming the importance of light in the activation of toxin production. Inin vivo experiments, the highest incidence and severity progress of the disease were observed at 21°C. With respect to the amounts of chlorophyll a, b, and total, regardless of treatment, the lowest levels were found in the area of the leaf with symptons compared to the area without symptoms.