Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Colombian/ Venezuelan Fusion Cuisine! Family-Run and Bursting with Rich Flavors, Sabores De Mi Tierra Is a Must Try!

B U F F A L O W I T H O U T B O R D E R S C U L T U R A L I N F O R M A T I O N P A C K E T CUISINE SERVED BY: SABORES DE MI TIERRA The second night of our Buffalo Without Borders TO GO series will be served by Sabores De Mi Tierra! In a colorful space on Niagara street, it is the only restaurant in Buffalo to boast Colombian/ Venezuelan fusion cuisine! Family-run and bursting with rich flavors, Sabores De Mi Tierra is a must try! Sabores De Mi Tierra, which translates to "flavors of my land" in English, was re-opened under new ownership in 2019. Diana and Edgar reestablished the Colombian favorite on Niagara St. Diana is from Colombia and Edgar, her husband, is from Venezuela but grew up in Colombia, making their menu a fusion of the two cuisines. Sabores De Mi Tierra is the only Colombian restaurant in Buffalo and before it was opened our Colombian population had to go to NYC to find the cuisines of their homeland. This is why the pair was so excited to open their restaurant in Buffalo, Diana said, "We are the only ones to offer Colombian food like this in Buffalo, and I want the community to learn more about our cuisine because it is the best food, the richest in spice and flavor!" Besides an array of spices, their cuisine relies heavily on the flavors of sautéed peppers, onions, and garlic. -

Check List Notes on Geographic Distribution Check List 13(2): 2091, 12 April 2017 Doi: ISSN 1809-127X © 2017 Check List and Authors

13 2 2091 the journal of biodiversity data 12 April 2017 Check List NOTES ON GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION Check List 13(2): 2091, 12 April 2017 doi: https://doi.org/10.15560/13.2.2091 ISSN 1809-127X © 2017 Check List and Authors First records of Sturnira bakeri Velazco & Patterson, 2014 (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) from Colombia Sebastián Montoya-Bustamante1, 3, Baltazar González-Chávez2, Natalya Zapata-Mesa1 & Laura Obando-Cabrera1 1 Universidad del Valle, Grupo de Investigación en Ecología Animal, Departamento de Biología, Apartado Aéreo 25360, Cali, Colombia 2 Universidad del Valle, Apartado Aéreo 25360, Cali, Colombia 3 Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: We evaluate the occurrence of S. bakeri in m). Therefore, there was a high probability that this species Colombia, a recently described species. We report seven inhabits northwestern Peru rather than elsewhere (Velaz- new records and include data on skull measurements of co & Patterson 2014). Recently, Sánchez & Pacheco these individuals and information on the new localities. A (2016) tested this hypothesis and reported the presence of discriminant analysis suggests that condyloincisive length S. bakeri from six localities in northwestern Peru. No fur- and dentary length are the most important measurements ther information has been published on S. bakeri and its to separate S. bakeri and S. luisi from S. lilium. However, geographic distribution remains obscure. Our aim was to to distinguish S. bakeri from S. luisi, we used discrete evaluate the occurrence of S. bakeri in Colombia, as well as characters proposed in the original descriptions of these to increase our knowledge of the morphological variation two taxa. -

New Insights Into the Microbiota of Moth Pests

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review New Insights into the Microbiota of Moth Pests Valeria Mereghetti, Bessem Chouaia and Matteo Montagna * ID Dipartimento di Scienze Agrarie e Ambientali, Università degli Studi di Milano, 20122 Milan, Italy; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (B.C.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5031-6782 Received: 31 August 2017; Accepted: 14 November 2017; Published: 18 November 2017 Abstract: In recent years, next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have helped to improve our understanding of the bacterial communities associated with insects, shedding light on their wide taxonomic and functional diversity. To date, little is known about the microbiota of lepidopterans, which includes some of the most damaging agricultural and forest pests worldwide. Studying their microbiota could help us better understand their ecology and offer insights into developing new pest control strategies. In this paper, we review the literature pertaining to the microbiota of lepidopterans with a focus on pests, and highlight potential recurrent patterns regarding microbiota structure and composition. Keywords: symbiosis; bacterial communities; crop pests; forest pests; Lepidoptera; next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies; diet; developmental stages 1. Introduction Insects represent the most successful taxa of eukaryotic life, being able to colonize almost all environments, including Antarctica, which is populated by some species of chironomids (e.g., Belgica antarctica, Eretmoptera murphyi, and Parochlus steinenii)[1,2]. Many insects are beneficial to plants, playing important roles in seed dispersal, pollination, and plant defense (by feeding upon herbivores, for example) [3]. On the other hand, there are also damaging insects that feed on crops, forest and ornamental plants, or stored products, and, for these reasons, are they considered pests. -

Colombia: Extractives for Prosperity May 2014 Colombia

Colombia: Extractives for Prosperity May 2014 Colombia Extractives for Prosperity Colombia: Extractives for Prosperity Capstone Report, School of International and Public Affairs, Columbia University Valle Avilés Pinedo Samantha Holt Michael Bellanton Michael Bellantoni Kine Martinussen Fernando Peinado Gustavo Rojas German Cash Daniel Mendoza Gustavo Rojas Maneesha Shrivastava Federico Sersale Alejandra Espinosa Nicholas Nassar Federico Sersale Carolyn Westeröd1 Supervised by Professor Jenik Radon, Esq. Colombia: Extractives for Prosperity May 2014 Acknowledgments The Columbia University School of International and Public Affairs’ Colombia Capstone group would like to acknowledge the many individuals and organizations that provided invaluable assistance in creating this report: - Professor Jenik Radon, the capstone advisor, for his mentorship and outstanding wisdom. - Fundacion Foro Nacional por Colombia, for helping plan our field trip to Colombia, and for their wisdom and valuable guidance through the development of this project. - Columbia University SIPA, for providing financial support for this Project. - The over 50 interviewees from government organizations, civil society, the oil industry, the mining industry, environmental specialists, academia, and elsewhere, who generously offered their time to meet with us in Colombia and New York. Their guidance was invaluable for the development of this Project. - The authors of the other reports in the Columbia University, School of International and Public Affairs Natural Resources: Potentials -

Undiscovered Colombia, Providencia and Panama City

18 days 11:31 01-09-2021 We are the UK’s No.1 specialist in travel to Latin As our name suggests, we are single-minded America and have been creating award-winning about Latin America. This is what sets us apart holidays to every corner of the region for over four from other travel companies – and what allows us decades; we pride ourselves on being the most to offer you not just a holiday but the opportunity to knowledgeable people there are when it comes to experience something extraordinary on inspiring travel to Central and South America and journeys throughout Mexico, Central and South passionate about it too. America. A passion for the region runs Fully bonded and licensed Our insider knowledge helps through all we do you go beyond the guidebooks ATOL-protected All our Consultants have lived or We hand-pick hotels with travelled extensively in Latin On your side when it matters character and the most America rewarding excursions Book with confidence, knowing Up-to-the-minute knowledge every penny is secure Let us show you the Latin underpinned by 40 years' America we know and love experience 11:31 01-09-2021 11:31 01-09-2021 There's some of the best-preserved colonial architecture in Latin America in the cities of Bogotá and Cartagena, and remarkable pre-Columbian artefacts in the San Agustín Archaeological Park.This holiday takes you to all of these, plus a few days on one of the Caribbean’s laid-back and quirkiest islands, English-speaking Providencia, which flies the Colombian flag. -

Evaluation of Nama Opportunities in Colombia's

EVALUATION OF NAMA OPPORTUNITIES IN COLOMBIA’S SOLID WASTE SECTOR WRITTEN BY: Leo Larochelle Michael Turner Michael LaGiglia CCAP RESEARCH SUPPORT: CENTER FOR CLEAN AIR POLICY Hill Consulting (Bogotá) OCTOBER 2012 Dialogue. Insight. Solutions. Acknowledgements This paper is a product of CCAP’s Mitigation Action Implementation Network (MAIN) and was written by Leo Larochelle, Michael Turner, and Michael LaGiglia of CCAP. This project was undertaken with the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Federal Department of the Environment. Special thanks are due to the individuals and organizations in Colombia who offered their time and assistance, through phone interviews or in-person discussions to help inform this work. The support of the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible was essential to the success of this report as well as help from the Steering Committee (made up of the Ministerio de Ambiente Vivienda Y Desarrollo Territorial, the Departamento Nacional de Planeación, the Ministerio de Ambiente y Desarrollo Sostenible, and the Superintendencia de Servicios Públicos Domiciliarios), representatives from Santiago de Cali (Empresa Pública de Gestión Integral de Residuos Sólidos de Cali, Departamento Administrativo para la Gestión del Medio Ambiente), Medellín (Area Metropolitana del Valle de Aburra Unidad Ambiental), Ibagué (Corporación Autónoma Regional del Tolima-Cortolima and Interaseo) and Sogamoso (Secretario de Desarrollo y Medio Ambiente and Coservicios). The views expressed in this paper represent those -

Unesco Creative Cities Network Popayán, Colombia Periodic Evaluation Report Creative City of Gastronomy 2020

UNESCO CREATIVE CITIES NETWORK POPAYÁN, COLOMBIA PERIODIC EVALUATION REPORT CREATIVE CITY OF GASTRONOMY 2020 GENERAL INFORMATION 2.1 Name of the city: Popayán 2.2 Country: Colombia 2.3 Creative field: Gastronomy 2.4 Date of designation: August 6, 2005 2.5 Date of submission of this periodic evaluation report: December 31, 2020 2.6 Entity responsible for preparing the report: Popayán Mayor's Office of Tourism 2.7 Previous reports and submission dates: February 28, 2016 2.8 Focal point: Juan Carlos López Castrillón: Mayor of Popayán alcaldia@popayan- cauca.gov.co Focal Point: Ms. Monika Ximena Anacona Quilindo Tourism Coordinator of the Municipality of Popayán, [email protected] Tel. + 57 – 3022902871 3.1 Popayán attended some annual meetings of the Network: 3.1.1. Popayán participated with chef Pablo Guzmán Illera who obtained recognition for the typical cuisine of the region with his participation in the 15th edition of the International Food Festival of Chengdu, held in China at the end of 2018. Within the framework of the festival, he was originally from Chengdu and by which this city became part of the network of creative cities of UNESCO. Chef Guzmán Illera won the awards for "Best presentation, best taste, Creativity" and "Foodies Choice", awarded in competition and by public choice. The chef presented a typical dish: El Tripazo Caucano, vacuum cooked; the pickle of ollucos; carantanta; and avocado emulsion were the dishes presented by the Colombian chef to the 200 festival goers. 3.1.2. Chef Pablo Guzmán Illera has also participated in events of the same network, such as the “Chef Challenge”, the “Unesco World Meeting of Creative Cities” in Belem (Brazil). -

Border Policy in Venezuela and Colombia

MASS VIOLENCE & ATROCITIES Border Policy in Venezuela and Colombia A Discussion Paper by Francisco Javier Sanchez C. Translated into English from the original Spanish version Context Colombia seeks to build a more open border policy. The Colombian Border Law of 1995 and the Andean Community standards promote Relations between Venezuela and Colombia deteriorated to a cross-border cooperation and planning, as well as the creation of breaking point after the Colombian Peace Agreement with the border integration zones. Due to the Venezuelan migration crisis, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia-People’s Army (FARC-EP) in Colombia created a border management agency, implemented a 2016. Today, the Colombian government recognizes Juan Guaidó as border mobility card, and discussed a bill to provide economic the legitimate interim president of Venezuela and considers Nicolás and social facilities to Cúcuta. A limited National Impact Plan was Maduro a usurper and his government a de facto regime. In refer- introduced, aimed at stimulating the economy and strengthening ence to Guaidó, there are limited diplomatic relations between his societies in the border areas and addressing their regular needs, representatives and Colombia, while there are no relations between which have increased because of Venezuelan migration. the Maduro government and Colombia following years of distrust. At the decision of Venezuela, formal crossing points along the Recommendations Colombian border have been officially closed since August 19, 2015, Given this context, the following proposals are presented: however there are unofficial openings during limited hours, though the consistency fluctuates. Since February 22, 2019, the crossing National Governments points at the border with the Venezuelan state of Táchira have been – Both governments should establish regular channels of com- closed to vehicular traffic, with pedestrian traffic allowed at the munication and cooperation, without delays. -

Guia De Rutas Verdes Pp1-100

Libro Rutas Verdes2 24/8/2005 10:52 AM Page 1 CVC más ágil, cercana y participativa Libro Rutas Verdes2 24/8/2005 10:52 AM Page 2 338.4791 C822rut CORPORACIÓN AUTÓNOMA REGIONAL DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA — CVC. Dirección de Gestión Ambiental— Dirección Técnica Ambiental Rutas Verdes del Valle del Cauca - Colombia / María Isabel Salazar Ramírez; [et. Al.] Santiago de Cali: CVC, 2005. 232 p.: il., mapas, fotografías 1. TURISMO 2.TURISMO CULTURAL 3.OFERTA TURÍSTICA 4.ECODESARROLLO. 5. ECOSISTEMAS I. Título II. SALAZAR RAMIREZ, María Isabel. III. HERNÁNDEZ CORRALES, Mónica. IV. PARRA VALENCIA, Germán. V. GARCÍA MENESES, Liliana VI. TRUJILLO SANDOVAL, Martha Yadira. RUTAS VERDES DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA - COLOMBIA © Corporación Autónoma Regional del Valle del Cauca — CVC — 2005 Publicación de la Dirección de Gestión Ambiental y la Dirección Técnica Ambiental. Comité Editorial: CVC: Dirección de Gestión Ambiental, Dirección Técnica Ambiental y Secretaría General. Gobernación del Valle del Cauca: Instituto para la Investigación y la Preservación del Patrimonio Cultural y Natural del Valle del Cauca INCIVA, Secretaría de Cultura y Turismo del Valle del Cauca. Textos: María Isabel Salazar Ramírez, Mónica Hernández Corrales, Germán Parra Valencia, Liliana García Meneses y Martha Yadira Trujillo Sandoval. Corrección de Estilo: CVC, Beatriz Canaval T. - INCIVA, Liliana García M. Impresión, diseño y diagramación: Ingeniería Gráfica S.A. Fotografía: Ver anexo Mapas: Paola Andrea Gómez Caicedo Primera Edición: 1200 ejemplares Editado y Publicado por: Carrera 56 11-36 Teléfono: 3310100 Ext. 328 -302 - 336 -Fax: 3310195 Web: http//www.cvc.gov.co Santiago de Cali, Valle del Cauca, Colombia PORTADA ISBN 958-8094-92-5 Arriba: Atardecer Pacífico Centro: Laguna de Sonso Abajo izquierda-derecha: Ninguna parte de esta obra puede ser reproducida, almacenada en Parque Natural Regional del sistema recuperable o transmitida en ninguna forma o por ningún Duende, Quebrada Perico, medio electrónico, mecánico, fotocopia, grabación u otros, sin el Paramillo de Barragan, previo permiso de la editorial. -

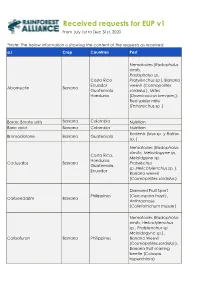

IIS 2020 Requests Overview

Received requests for EUP v1 From July 1st to Dec 31st, 2020 *Note: The below information is showing the content of the requests as received. a.i Crop Countries Pest Nematodes ( Radophulus similis, Radopholus sp, Costa Rica Pratylenchus sp ), Banana Ecuador weevil ( Cosmopolites Abamectin Banana Guatemala sordidus ), Mites Honduras (Dysmicoccus brevipes ), Red spider mite (Tetranychus sp .) Borax; Borate salts Banana Colombia Nutrition Boric acid Banana Colombia Nutrition Rodents ( Mus sp. y Rattus Bromadiolone Banana Guatemala sp. ) Nematodes ( Radopholus silmillis, Meloidogyne sp, Costa Rica, Meloidgune sp, Honduras, Cadusafos Banana Pratylechus Guatemala, sp.,Helicotylenchus sp. ), Ecuador Banana weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus ) Diamond Fruit Sport Philippines (Cercospora hayii ), Carbendazim Banana Anthracnose (Colletotrichum musae ) Nematod es (Radopholus similis, Helicotylenchus sp., Pratylenchus sp. Meloidogyne sp.) , Carbofuran Banana Philippines Banana Weevil (Cosmopolites sordidus ), Banana fruit scarring beetle (Colaspis hyperchlora) a.i Crop Countries Pest Black Sigatoka Ecuador, Costa (Mycosphaerella fijiensis ), Rica, Philippines, Yellow Sigatoka Chlorothalonil Banana Honduras, (Mycosphaerella Guatemala, musicola ), Banana Colombia Freckle ( Phyllosticta musarum ) Mealybug ( Dysmicoccus brevipes, Pseudococcus elisae, Pseudococcus sp, Ferrista sp ), Dysmicoccus sp , Scale insects (Aspidiotus destructor, Diaspis boisduvalii ), Thrips (Thrips florum, Franckliniella spp, Chaetanaphothrips signipennis ), Banana fruit Philippines, -

Dar Centro Norte

INFORME DE GESTIÓN AUDIENCIA PÚBLICA AMBIENTAL DE SEGUIMIENTO AL PLAN DE ACCIÓN 2012-2015 Y RENDICIÓN DE CUENTAS 2013 DAR CENTRO NORTE Laguna El Búho, Nacimiento del río Tibí, cuenca río Bugalagrande, municipio de Sevilla Tuluá, Marzo de 2014 TABLA DE CONTENIDO Pág. INTRODUCCIÓN 2 1. AVANCE DEL PLAN FINANCIERO 3 2. INGRESOS Y GASTOS DE FUNCIONAMIENTO DE INVERSIÓN 4 3. AVANCE DE LAS METAS FÍSICAS DE PROCESOS Y PROYECTOS ENERO – DICIEMBRE DE 2013 5 4. GENERALIDADES DE LA DIRECCIÓN AMBIENTAL REGIONAL CENTRO NORTE 6 5. SITUACIONES AMBIENTALES RELEVANTES 8 6. COMPROMISOS ADQUIRIDOS DE LA AUDIENCIA ANTERIOR CON LAS ACCIONES IMPARTIDAS. 11 7. EJECUCION PRESUPUESTAL DAR CENTRO NORTE 13 8. INVERSIÓN MUNICIPAL 14 9. INVERSIÓN POR CUENCA 15 10. GESTIÓN REALIZADA POR PROGRAMA 10.1. PROGRAMA 1 - Gestión integral de la biodiversidad y sus 16 servicios ecosistémicos. 78 10.2. PROGRAMA 2 - Gestión Integral del Recurso Hídrico. 10.3. PROGRAMA 3 - Medidas de Prevención, Mitigación y 93 Adaptación al Cambio Climático en la Gestión. 10.4. PROGRAMA 4 - Alianzas Estratégicas en Cuencas y 101 Ecosistemas Compartidos, Bienes Públicos Regionales 104 10.5. PROGRAMA 5 - Sostenibilidad de Actividades Productivas 10.6. PROGRAMA 6 - Protección y mejoramiento del Ambiente en 129 Asentamientos Urbanos 10.7. PROGRAMA 7 - Educación y Cultura Ambiental Participativa 134 e Incluyente 11. PROYECTOS DE INTERÉS PARA TODA LA JURISDICCIÓN DE LA 157 CVC 12. SERVICIO DE ATENCIÓN AL USUARIO 168 Informe de Gestión 2013 - Dar Centro Norte 2 INTRODUCCIÓN La Constitución Política de Colombia determina que “Todas las entidades y organismos de la administración tienen la obligación de desarrollar su gestión acorde con los principios de la democracia participativa y la democratización de la gestión; de igual forma podrán convocar audiencias públicas para discutir lo relacionado con la formulación, ejecución y evaluación de políticas y programas a cargo de la entidad”. -

Informe De Gestión - 2020

DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA Versión 1.0 INFORME DE GESTION 2020 17/01/2020 VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. PROGRAMA AGUA PARA LA PROSPERIDAD PLAN DEPARTAMENTAL DE AGUA DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA PAP-PDA INFORME DE GESTIÓN - 2020 SANTIAGO DE CALI, FEBRERO DE 2020 DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA Versión 1.0 INFORME DE GESTION 2020 17/01/2020 VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. INFORME DE GESTIÓN – 2020 La política para el sector de agua potable y saneamiento básico - “Agua para la Prosperidad” en el Valle del Cauca se lleva a cabo por parte del Gobierno Departamental a través de Vallecaucana de Aguas S.A. E.S.P., entidad creada mediante escritura pública No. 4792 de octubre de 2009, con un capital suscrito y pagado de $500 millones, de los cuales el 94.4% ($472.000.000) corresponde a la Gobernación y el 5.6% restante ($28.000.000) a 14 municipios, a saber: Alcalá, Andalucía, Ansermanuevo, Argelia, Buga, Bugalagrande, El Águila, El Cairo, La Cumbre, Riofrio, San Pedro, Sevilla, Toro y Vijes. VALLECAUCANA DE AGUAS S.A. E.S.P. PARTICIPACIÓN ACCIONARIA No. ACCIONISTAS Porcentaje 1 MUNICIPIO DE ALCALA 0,4% 2 MUNICIPIO DE ANDALUCIA 0,4% 3 MUNICIPIO DE ANSERMANUEVO 0,4% 4 MUNICIPIO DE ARGELIA 0,4% 5 MUNICIPIO DE BUGA 0,4% 6 MUNICIPIO DE BUGALAGRANDE 0,4% 7 MUNICIPIO DE EL AGUILA 0,4% 8 MUNICIPIO DE EL CAIRO 0,4% 9 MUNICIPIO DE LA CUMBRE 0,4% 10 MUNICIPIO DE RIOFRIO 0,4% 11 MUNICIPIO DE SAN PEDRO 0,4% 12 MUNICIPIO DE SEVILLA 0,4% 13 MUNICIPIO DE TORO 0,4% 14 MUNICIPIO DE VIJES 0,4% 15 DEPARTAMENTO DEL VALLE DEL CAUCA 94,4% TOTAL 100,0% Vallecaucana