Colombia: Extractives for Prosperity May 2014 Colombia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Undiscovered Colombia, Providencia and Panama City

18 days 11:31 01-09-2021 We are the UK’s No.1 specialist in travel to Latin As our name suggests, we are single-minded America and have been creating award-winning about Latin America. This is what sets us apart holidays to every corner of the region for over four from other travel companies – and what allows us decades; we pride ourselves on being the most to offer you not just a holiday but the opportunity to knowledgeable people there are when it comes to experience something extraordinary on inspiring travel to Central and South America and journeys throughout Mexico, Central and South passionate about it too. America. A passion for the region runs Fully bonded and licensed Our insider knowledge helps through all we do you go beyond the guidebooks ATOL-protected All our Consultants have lived or We hand-pick hotels with travelled extensively in Latin On your side when it matters character and the most America rewarding excursions Book with confidence, knowing Up-to-the-minute knowledge every penny is secure Let us show you the Latin underpinned by 40 years' America we know and love experience 11:31 01-09-2021 11:31 01-09-2021 There's some of the best-preserved colonial architecture in Latin America in the cities of Bogotá and Cartagena, and remarkable pre-Columbian artefacts in the San Agustín Archaeological Park.This holiday takes you to all of these, plus a few days on one of the Caribbean’s laid-back and quirkiest islands, English-speaking Providencia, which flies the Colombian flag. -

Colombian Peso Forecast Special Edition Nov

Friday Nov. 4, 2016 Nov. 4, 2016 Mexican Peso Outlook Is Bleak With or Without Trump Buyside View By George Lei, Bloomberg First Word The peso may look historically very cheap, but weak fundamentals will probably prevent "We're increasingly much appreciation, regardless of who wins the U.S. election. concerned about the The embattled currency hit a three-week low Nov. 1 after a poll showed Republican difference between PDVSA candidate Donald Trump narrowly ahead a week before the vote. A Trump victory and Venezuela. There's a could further bruise the peso, but Hillary Clinton wouldn't do much to reverse 26 scenario where PDVSA percent undervaluation of the real effective exchange rate compared to the 20-year average. doesn't get paid as much as The combination of lower oil prices, falling domestic crude production, tepid economic Venezuela." growth and a rising debt-to-GDP ratio are key challenges Mexico must address, even if — Robert Koenigsberger, CIO at Gramercy a status quo in U.S. trade relations is preserved. Oil and related revenues contribute to Funds Management about one third of Mexico's budget and output is at a 32-year low. Economic growth is forecast at 2.07 percent in 2016 and 2.26 percent in 2017, according to a Nov. 1 central bank survey. This is lower than potential GDP growth, What to Watch generally considered at or slightly below 3 percent. To make matters worse, Central Banks Deputy Governor Manuel Sanchez said Oct. Nov. 9: Mexico's CPI 21 that the GDP outlook has downside risks and that the government must urgently Nov. -

2022 Cartagena Nomadness Itinerary Open

2022 ITINERARY 2022 CULTURE IN CARTAGENA N0MADNESS TRIPS WEEK 1: FEBRUARY 23-28, 2022 WEEK 2: MARCH 2-7, 2022 WEEK 3: MARCH 9-14, 2022 CARTAGENA, COLOMBIA DAY 1 DETAILS ALL DAY- ARRIVALS: AIRPORT PRELIMINARY SHUTTLE PICKS YOU UP FROM CTG, * AND BRINGS YOU TO OUR HOST HOTEL. GET SETTLED IN AND WE'LL Itinerary is identical for all weeks of the trip, thus instead ITINERARY SEE YOU FOR DINNER. of specific dates, you'll see itinerary points noted by trip - GROUP WELCOME DINNER day. Please note this is preliminary, as the full itinerary with in DAY 2 depth descriptions, hotel details, optional add ons, and BREAKFAST pricing details will be sent on Sunday, May 30th to those approved from the preliminary registration for this DEPARTURE FOR 'THE REAL CARTAGENA' TOUR specific trip. WHERE WE ARE IMMERSED IN LOCAL CULTURE THROUGH FOOD, MUSIC, AND CUSTOMS. ON THIS TOUR WE SEE AND LEARN ABOUT THE AIRPORT: AFRICAN INFLUENCE THAT IS SO PROMINENT CArtagena - CTG AROUND CARTAGENA. LOCAL LUNCH CURRENCY: COLOMBIAN PESO - COP THE FAMED MUD VOLCANO. THIS AFTERNOON YOU'LL BE ABLE TO TAKE A MUD BATH IN THE NATURAL VOLCANO ABOUT 40 MINUTES Meals Covered in BUY IN: OUTSIDE OF THE CITY. All Breakfasts, three lunches, DAY 3 Welcome Dinner, Farewell Dinner, BREAKFAST DEPARTURE FOR PLAYA BLANCA BEACH. AFTER YOUR DAY HOTEL: OF CULTURAL IMMERSION, YOU GET TO REST AND RELAX ON THE BEACH, ENJOY THE SUN, AND AFROCOLOMBIAN MUSIC HOTEL INTERCONTINENTAL VIBES. LOCAL LUNCH PRICING: DAY 4 $2400 Total BREAKFAST DEPARTURE FOR TOUR OF PALENQUE. NOW WE $300 - BUYIN on Sun. -

Crisis Response Revision of Colombia Country Strategic Plan (2017–2021) and Corresponding Budget Increase

Executive Board Annual session Rome, 10–14 June 2019 Distribution: General Agenda item 8 Date: 23 May 2019 WFP/EB.A/2019/8-D/1 Original: English Operational matters For information Executive Board documents are available on WFP’s website (https://executiveboard.wfp.org). Crisis response revision of Colombia country strategic plan (2017–2021) and corresponding budget increase Current Change Revised April 2017 – Duration N/A N/A December 2021 Beneficiaries 1 195 000 963 260 2 158 260 (USD) Total cost 161 240 066 93 303 121 254 543 187 Transfer 119 919 313 78 450 914 198 370 227 Implementation 18 790 551 5 928 073 24 718 624 Total transfer and implementation 138 709 864 84 378 987 223 088 851 Adjusted direct support costs 12 577 691 3 229 577 15 807 268 Subtotal 151 287 555 87 608 564 238 896 119 Indirect support costs (6.5 percent) 9 952 512 5 694 557 15 647 068 Gender and age marker* 2A * http://gender.manuals.wfp.org/en/gender-toolkit/gender-in-programming/gender-and-age-marker/. Rationale 1. Following the official request by the Government of Colombia to the United Nations to support the response to the Venezuela migrant crisis in February 2018, WFP activated a Level 2 emergency response targeting 350,000 vulnerable migrants and members of the Focal points: Mr M. Barreto Mr C. Scaramella Regional Director Country Director Latin America and the Caribbean email: [email protected] email: [email protected] World Food Programme, Via Cesare Giulio Viola, 68/70, 00148 Rome, Italy WFP/EB.A/2019/8-D/1 2 host communities for eight months in the departments of Arauca, La Guajira, Nariño and Norte de Santander. -

Liberian Studies Journal

VOLUME VI 1975 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL (-011111Insea.,.... , .. o r r AFA A _ 2?-. FOR SALE 0.1+* CHARLIE No 4 PO ßox 419, MECNttt+ ST tR il LIBERIA C MONROVIA S.. ) J;1 MMNNIIN. il4j 1 Edited by: Svend E. Holsoe, Frederick D. McEvoy, University of Delaware Marshall University PUBLISHED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY, UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor African Art Stores, Monrovia. (Photo: Jane J. Martin) PDF compression, OCR, web optimizationi using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME VI 1975 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL EDITED BY Svend E. Holsoe Frederick D. McEvoy University of Delaware Marshall University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Igolima T. D. Amachree Western Illinois University J. Bernard Blamo Mary Antoinette Brown Sherman College of Liberal & Fine Arts William V. S. Tubman Teachers College University of Liberia University of Liberia George E. Brooks, Jr. Warren L. d'Azevedo Indiana University University of Nevada David Dalby Bohumil Holas School of Oriental and African Studies Centre des Science Humaines University of London Republique de Côte d'Ivoire James L. Gibbs, Jr. J. Gus Liebenow Stanford University Indiana University Bai T. Moore Ministry of Information, Cultural Affairs & Tourism Republic of Liberia Published at the Department of Anthropology, University of Delaware James E. Williams Business Manager PDFb compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS page THE LIBERIAN ECONOMY IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE STATE OF AGRICULTURE AND COMMERCE, by M. B. Akpan 1 THE RISE AND DECLINE OF KRU POWER: FERNANDO PO IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY, by Ibrahim K. -

Detailed Itinerary

TRAVEL PLANNING GUIDE Colombia’s Colonial Jewels & the Coffee Triangle 2020 Small Groups: 8-16 travelers—guaranteed! (average of 14) Overseas Adventure Travel ® The Leader in Small Groups on the Road Less Traveled 1 Overseas Adventure Travel ® 347 Congress Street, Boston, MA 02210 Dear Traveler, We've always felt that real travel is about meeting new people and discovering unfamiliar cultures—elements that are at the heart of every O.A.T. adventure. In the following pages, you'll find detailed information about the adventure you've expressed interest in, including a detailed day-to-day itinerary. We've also included visa requirements, regional weather conditions, local currency and health information—even a few film and book recommendations for further inspiration about this destination. Exploring the world with O.A.T. allows you to experience the awe and wonder of familiar and far- flung destinations in a small group of 8-16 travelers (with an average of 14). And since no one brings a new location to life better than someone who makes his or her home in that destination, you'll be accompanied by one of our local Trip Leaders, who will serve as your chief experience leader—helping to ensure you're getting the personalized experiences you're looking for. With O.A.T. you'll benefit from our decades-long experience introducing the world to American travelers at the best value anywhere. We have the lowest prices in the industry and offer FREE Single Supplements—which means solo travelers never pay more for their own hotel or cabin. -

Colombia Country Fact Sheet

National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Page 1 of 4 Home > Research > National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Country Fact Sheet COLOMBIA April 2007 Disclaimer 1. GENERAL INFORMATION Official name Republic of Colombia. Geography Colombia is located at the northern point of South America and shares borders with Panama, Ecuador, Peru, Brazil and Venezuela. Colombia has a total of 3,208 km of coastline on the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. The total area is 1,038,700 km2. The coast has a tropical climate, the interior plateaux are temperate and some Andean areas have snow year-round. Population and density Population: 43,593,035 (July 2006 estimate). Density: 39.7 persons per km2. Principal cities and populations (2005 estimate) Bogota (political capital) 8,350,000; Medellin 3,450,000; Cali 2,700,000; Barranquilla 1,925,000; Cartagena 1,075,000. Languages Spanish (official). Religions Catholic 90%. Ethnic groups Mestizo 58%, white 20%, mulatto 14%, black 4%, mixed black-Amerindian 3%, Amerindian 1%. Approximately 75 % of Colombians are of mixed-blood. Demographics http://www.irb-cisr.gc.ca:8080/Publications/PubIP_DI.aspx?id=209&pcid=359 2/23/2011 National Documentation Packages, Issue Papers and Country Fact Sheets Page 2 of 4 Population growth rate: 1.46% (2006 estimate). Infant mortality rate: 20.35 deaths/1,000 live births. Life expectancy at birth: 72.6 (2004). Fertility rate: 2.54 children born/woman (2006 estimate). Literacy: 92.8% of people aged 15 and older can read and write (2004). Currency Colombian Peso (COP). -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Report No: 21723-CO Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ONA PROPOSED GRANT FROM THE Public Disclosure Authorized GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY TRUST FUND IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 11.8 MILLION (US$15.0 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE INSTITUTO DE INVESTIGACION DE RECURSOS BIOLOGICOS ALEXANDER VON HUMBOLDT FOR AN ANDEAN REGION CONSERVATION AND SUSTAINABLE USE OF BIODIVERSITY PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized February 12, 2001 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Colombia, Mexico & Venezuela Country Management Unit Latin America and the Caribbean Regional Office CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective January, 200 1) Currencv Unit = Colombian Peso COP$1.0 = US$.00044 US$1.00 = COP$2252 FISCAL YEAR July 1,2000 - June 31, 2001 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS CAR Regional Autonomous Corporation (Corporaci6nAut6noma Regional) CAR Regional Autonomous Corporation of Cundinamarca CARDER Regional Autonomous Corporation of Risaralda CAS Country Assistance Strategy CAS Regional Autonomous Corporation of Santander CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CDMB Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Meseta de Bucaramanga CI Conservation International CONIF National Corporation for Forestry Research (Corporaci6nNacional de Investigaci6ny Fomento Forestal) COP Conference of the Parties of the CBD CORMACARENA Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Macarena Region CORPOAMAZONAS Regional Autonomous Corporation of the Amazonas region CORPOBOYACA Regional Autonomous Corporation -

Coffee Cultural Landscape of Colombia

Republic of Colombia PCC COFFEE CULTURAL LANDSCAPE PAISAJE CULTURAL CAFETERO- Management Plan Unofficial Translation Coordinating Committee: Ministry of Culture Colombian Coffee Growers’ Federation Bogotá, September 2009 1 1 Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................. 5 2. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE COFFEE CULTURE LANDSCAPE 2.1. DESCRIPTION ........................................................................ 2.1.1. The human, family centered, generational, and historical efforts related to the production of quality coffee, within a framework of sustainable human development ................................................................... 11 2.1.2. Coffee culture for the world ......................................... 16 2.1.3. Strategic social capital built around its coffee growing institutions 29 2.1.4.The relationship between tradition and technology: Guaranteeing the quality and sustainability of a product 34 2.1 2.2. THE PCC’S CURRENT STATE OF CONSERVATION 2.2.1.The human, family centered, generational, and historical efforts related to the production of quality coffee, within a framework of sustainable human development 2.2.2.Coffee culture for the world 2.2.3.Strategic social capital built around coffee growing institutions 51 2 2 2.2.4.The relationship between tradition and technology: Guaranteeing product quality and sustainability 53 2.3. FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE PCC ............................................... 56 2.3.1.Developmental pressures 2.3.2. Environmental pressures -

Green Opportunities with an Orange Touch in Colombia Business Leads in the Horticultural Sector Ideavelop & Verbos Business Development

Green Opportunities with an Orange Touch in Colombia Business leads in the horticultural sector Ideavelop & Verbos Business Development 1 Green Opportunities with an Orange Touch in Colombia Business leads in the horticultural sector Commissioned by: Netherlands Enterprise Agency, Transition Facility Colombia Authors Ideavelop S.A.: - Edwin Smit, Director Ideas - Renee Snijders, Director Development Verbos Business Development: - Aart van den Bos, Director Ideavelop is a Dutch consultancy agency based in Costa Rica and specialized in business development and marketing in international horticulture with a focus on the European and the Latin American market. Verbos Business Development is based in the Netherlands and involved in International business development, Corporate Social Responsibility, Financial engineering and Interim Management in the agribusiness sector. Verbos works for the private sector, government, institutes and NGO’s. Version: San Jose & Naaldwijk, 20 August 2014 2 Preface In April 2014, Netherlands Enterprise Agency requested Ideavelop and Verbos Business Development to carry out a market survey on the opportunities for the Dutch horticultural sector in Colombia as part of the so-called ‘Transition Facility’. The Transition Facility is a program focused on improving cooperation between selected sectors in the Netherlands and three upcoming markets (Colombia, South Africa and Vietnam). Horticulture is one of these priority sectors. It often turns out that the bad image of Colombia withholds Dutch companies to investigate the opportunities in Colombia. The Dutch companies often do not know what opportunities there are or Colombia is not even selected as a potential interesting (export) market. This hurdle can be overcome by mapping market opportunities in the Horticultural Sector in Colombia. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Annual

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Annual Report on Form 20-F/A REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ____________ to ___________ OR SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report __________________ Commission file number: 001-34175 ECOPETROL S.A. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of Registrant’s name into English) REPUBLIC OF COLOMBIA (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Carrera 7 No. 37 – 69 BOGOTA – COLOMBIA (Address of principal executive offices) Alejandro Giraldo Investor Relations Officer [email protected] Tel. (571) 234 4254 Fax. (571) 234 5628 Calle 37 N.7-43 Piso.3 Bogota, Colombia (Name, Telephone, E-Mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered: American Depository Shares (as evidenced by American Depository Receipts), each representing the right to receive 20 Common Shares New York Stock Exchange Ecopetrol Common Shares par value Ps$250 per share* New York Stock Exchange *Not for trading but only in connection with the registration of the American Depositary Shares pursuant to the requirements of the SEC. -

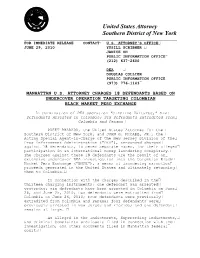

Gomez, Jader Et Al. Indictment

United States Attorney Southern District of New York FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: U.S. ATTORNEY'S OFFICE JUNE 29, 2010 YUSILL SCRIBNER JANICE OH PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (212) 637-2600 DEA DOUGLAS COLLIER PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE (973) 776-1143 MANHATTAN U.S. ATTORNEY CHARGES 18 DEFENDANTS BASED ON UNDERCOVER OPERATION TARGETING COLOMBIAN BLACK MARKET PESO EXCHANGE In Culmination of DEA Operation "Circling Vultures," Six Defendants Arrested in Colombia; Six Defendants Extradited From Colombia and Panama PREET BHARARA, the United States Attorney for the Southern District of New York, and JOHN G. McCABE, JR., the Acting Special Agent-in-Charge of the New Jersey Division of the Drug Enforcement Administration ("DEA"), announced charges against 18 defendants, in seven separate cases, for their alleged participation in an international money laundering conspiracy. The charges against these 18 defendants are the result of an extensive undercover DEA investigation into the Colombian Black Market Peso Exchange ("BMPE"), a means of laundering narcotics proceeds generated in the United States and ultimately returning them to Colombia. In connection with the charges described in the thirteen charging instruments: one defendant was arrested yesterday; six defendants have been arrested in Colombia on June 24, and June 25, 2010; two defendants were extradited from Colombia on June 26, 2010; four defendants were previously extradited from Colombia and Panama; four defendants were previously arrested in New Jersey and Florida; and one defendant remains at large. As alleged in the Indictments, Superseding Indictments, and criminal Complaints previously filed in connection with the investigation, and other documents filed in Manhattan federal court: The BMPE is a means of laundering narcotics proceeds and transmitting the proceeds to the owners of the proceeds in countries of origin for narcotics such as Colombia.