Changes in Symbols

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Alligier La Costruzione Dell'opinione Pubblica Nel Caffè

Marine Alligier La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffè 1764-1766 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALLIGIER Marine, La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffè 1764-1766, sous la direction de Pierre Girard. - Lyon : Université Jean Moulin (Lyon 3), 2017. Mémoire soutenu le 05/07/2017. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document diffusé sous le contrat Creative Commons « Paternité – pas d’utilisation commerciale - pas de modification » : vous êtes libre de le reproduire, de le distribuer et de le communiquer au public à condition d’en mentionner le nom de l’auteur et de ne pas le modifier, le transformer, l’adapter ni l’utiliser à des fins commerciales. Université Jean Moulin – Lyon 3 Faculté des langues Département d’italien Marine ALLIGIER La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffaf è 1764-1766 Mémoire de Master Recherche Sous la directtion de Pierre GIRARD Professeur des Universités Année universitaire 2016-2017 Remerciements J’adresse mes sincères remerciements à Monsieur Pierre Girard pour ses conseils et ses remarques éclairantes, ses précieux encouragements et sa disponibilité. In copertina : « L’accademia dei Pugni » di Antonio Perego, Collezione Sormani Andreani, 1762. Da sinistra a destra: Alfonso Longo (di spalle), Alessandro Verri, Giambattista Biffi, Cesare Beccaria, Luigi Lambertenghi, Pietro -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications the BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/130193 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE SHAKESPEARE'S RECEPTION IN 18TH CENTURY TITLE ITALY: THE CASE OF HAMLET AUTHOR Gabriella PETRONE FRESCO DEGREE PhD AWARDING Warwick University BODY DATE 1991 THESIS DX177597 NUMBER THIS THESIS HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis submitted for microfilming. Every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction. Some pages may have indistinct print, especially if the original papers were poorly produced or if awarding body sent an inferior copy. If pages are missing, please contact the awarding body which granted the degree. Previously copyrighted materials (journals articles, published texts etc.) are not filmed. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that it's copyright rests with its author and that no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION L’homme est la mesure des choses. […] La biographie est le fondement même de l’histoire. Franco Venturi, dans Dal trono al- l’al bero della libertà, I, Rome, 1991, p. 24. « L’homme est un animal capable de toutes les contradictions ». Cette phrase tirée du Petit commentaire d’un galant homme de mauvaise humeur1 résonne comme un défi lancé à l’optimisme progressiste du siècle des Lumières. C’est aussi une promesse de difficulté pour qui tente de saisir la logique d’une pensée au cœur de laquelle s’inscrit le relativisme. Né à Milan en 1741, Alessandro Verri avait fourbi ses premières armes dans Le Café. Dirigé par son frère Pietro, ce périodique nourri de culture française entendait soutenir et stimuler la politique réformatrice modérée mise en œu- vre en Lombardie par de hauts fonctionnaires de l’administration des Habsbourg, qui s’était attelée à un programme de « fondation ou refondation de l’État moderne »2. Il mourut à Rome, à soixante- quinze ans, romancier reconnu, apôtre de la Restauration monar- chique et fervent défenseur de l’Église. Ce raccourci biographique souligne l’apparente contradiction du parcours intellectuel d’Ales- sandro Verri : d’un côté, sa production milanaise développe une réflexion sur la modernisation des institutions juridiques, une cri- tique des académies littéraires et une satire des mœurs ; de l’autre, ses écrits romains témoignent d’une adhésion aux canons du clas- sicisme et aux thèses du conservatisme catholique. Cet intrigant paradoxe de l’esprit verrien possède quelque chose d’inattendu et de séduisant : le jeune homme des Lumières, devenu l’homme de la nuit et des sépulcres, un conservateur, si ce n’est un réactionnaire, aurait-il embrassé les deux âmes de son siècle, les Lumières et les anti-Lumières, l’encyclopédisme et la contre-révolution ? 1 Comentariolo di un galantuomo di mal umore, che ha ragione, sulla definizione : l’uomo è un animale ragionevole, in cui si vedrà di che si tratta, dans Il Caffè, p. -

Addio Teresa Blasco, Addio Marchesina Beccaria»

Quaderns d’Italià 10, 2005 95-111 Dietro il Retablo: «Addio Teresa Blasco, addio Marchesina Beccaria» Giovanni Albertocchi Universitat de Girona Abstract Teresa Blasco, la donna di cui si innamora il protagonista di Retablo, Fabrizio Clerici, è un personaggio storico, moglie di Cesare Beccaria e protagonista delle cronache della Milano illuminista. L’articolo, utilizzando documenti dell’epoca, ricostruisce le vicende di Teresa, dall’epoca del suo tormentato matrimonio con l’autore de Dei delitti e delle pene, fino alla sua morte. Parole chiave: matrimonio, «Accademia dei pugni», Verri, Beccaria. Abstract Teresa Blasco, the woman that Fabrizio Clerici, the protagonist of Retablo, is in love with, is a historical character, wife of Cesare Beccaria and protagonist of the chronicles of the Milan followers of the Enlightenment movement. The article, using documents from the period, rebuilds the vicissitudes of Teresa’s life, from the time of her tormented marriage to the author of Dei delitti e delle pene, until her death. Keywords: marriage, «Accademia dei pugni», Verri, Beccaria. Fabrizio Clerici, il protagonista di Retablo, conosce Teresa Blasco in una festa che i genitori di lei danno nella villa di Gorgonzola, nei pressi di Milano, dove stanno trascorrendo la villeggiatura. È una splendida serata estiva del 1760. Il giovane rimane abbagliato da questa diciassettenne che gli appare — scrive Vincenzo Consolo — «del color vestita del nascente verde, in un impareggia- bile splendore, nell’odore soave dell’ambra, del nardo e della rosa».1 Ma non è il solo, purtroppo, ad ammirare lo spettacolo. Intorno a lei ronzano come mosconi i giovani rampolli dell’alta società milanese. -

Abstracts of Papers / Résumés Des Communications S – Z

Abstracts of Papers / Résumés des communications S – Z Abstracts are listed in alphabetical order of Les résumés sont classés par ordre presenter. Names, paper titles, and alphabétique selon le nom du conférencier. institutional information have been checked Les noms, titres et institutions de and, where necessary, corrected. The main rattachement ont été vérifiés et, le cas text, however, is in the form in which it was échéant, corrigés. Le corps du texte reste originally submitted to us by the presenter dans la forme soumise par le/la participant.e and has not been corrected or formatted. et n'a pas été corrigé ou formaté. Les Abstracts are provided as a guide to the résumés sont fournis pour donner une content of papers only. The organisers of the indication du contenu. Les organisateurs du congress are not responsible for any errors or Congrès ne sont pas responsables des erreurs omissions, nor for any changes which ou omissions, ni des changements que les presenters make to their papers. présentateurs pourraient avoir opéré. Wout Saelens (University of Antwerp) Enlightened Comfort: The Material Culture of Heating and Lighting in Eighteenth-Century Ghent Panel / Session 454, ‘Enlightenment Spaces’. Friday /Vendredi 14.00 – 15.45. 2.07, Appleton Tower. Chair / Président.e : Elisabeth Fritz (Friedrich Schiller University, Jena) As enlightened inventors like Benjamin Franklin and Count Rumford were thinking about how to improve domestic comfort through more efficient stove and lamp types, the increasing importance of warmth and light in material culture is considered to have been one of the key features of the eighteenth-century ‘invention of comfort’. -

La Milano Giudiziaria Del XVII Secolo. Da Pietro Verri Ad Alessandro Manzoni, Il Punto Di Vista Della Criminologia

006-12 • Criminologia_Layout 1 18/07/11 09.44 Pagina 6 La Milano giudiziaria del XVII secolo. Da Pietro Verri ad Alessandro Manzoni, il punto di vista della criminologia The Milan court of the seventeenth century. From Pietro Verri to Alessandro Manzoni, the point of view of criminology Adolfo Francia Parole chiave: giustizia • processo agli Untori • tortura • anomia • narrazione Riassunto L’articolo propone alcuni spunti di riflessione sul tema della giustizia a partire dalla “Storia della colonna Infame” di A. Manzoni che narra della condanna a morte di Mora e Piazza, accusati di essere “untori” in una Milano seicentesca alle prese con un’epidemia di peste. La narrazione di Manzoni risulta di particolare interesse agli occhi di un criminologo per varie ragioni. Innanzitutto il tema al centro della narrazione: Manzoni mette in evidenza come i giudici del XVII secolo a Milano (come quelli di tutti i tempi, e alcune ricerche lo dimostrano) assurgono a portavoce della cultura del momento e sono i portatori delle istanze del gruppo sociale (o dei gruppi di potere che rappresentano) da cui fanno fatica a discostarsi. In seguito va segnalata l’ambientazione, di grande interesse criminologico: si parla di un processo avvenuto nel secolo di Ferro (XVII secolo) caratterizzato da violenza inar- rivabile, disfacimento dei legami sociali e di crisi anomica della giustizia. Infine, da un punto di vista di “narratologia criminologica” conta lo stile narrativo di Manzoni, criminologo ante litteram, che denuncia l’ingiustizia mescolando il linguaggio della verosimi- glianza con quello delle emozioni. I temi trattati da Manzoni coincidono con quelli al centro di “Osservazioni sulla Tortura” di Verri, opera fondamentale che segna l’inizio della criminologia dimostrando in modo pratico che senza la tortura il processo agli untori non avrebbe avuto l’epilogo che conosciamo. -

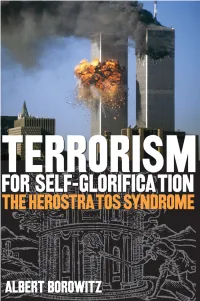

Terrorism for Self-Glorification

Terrorism for Self-Glorification introduction i This page intentionally left blank ii introduction Terrorism for Self-Glorification The Herostratos Syndrome Albert Borowitz The Kent State University Press Kent and London introduction iii © by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio all rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number isbn 0-87338-818-6 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Borowitz, Albert, – Terrorism for self-glorification : the herostratos syndrome / Albert Borowitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. --- (hardcover : alk. paper) ∞ . Terrorism. Violence—Psychological aspects. Aggressiveness. Herostratus. I. Title. .'—dc British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available. iv introduction In memory of Professor John Huston Finley, who, more than half a century ago, first told me about the crime of Herostratos. introduction v This page intentionally left blank vi introduction Contents Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note x Introduction xi The Birth of the Herostratos Tradition The Globalization of Herostratos The Destroyers The Killers Herostratos at the World Trade Center The Literature of Herostratos Since the Early Nineteenth Century Afterword Appendix: Herostratos in Art and Film Notes Index introduction vii This page intentionally left blank viii introduction Acknowledgments First and foremost my thanks go to my wife, Helen, who has contributed immeasurably to Terrorism for Self-Glorification, providing fresh insights into Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, guiding me through mountains of works on modern terrorism, and reviewing my manuscript at many stages. I am also grateful to Dr. Jeanne Somers, associate dean of the Kent State University Libraries, for her ingenuity and persistence in locating rare volumes from the four corners of the world. -

Alessandro Manzoni, Mid 19Th Century, Oil on Canvas, Sistema Museale Urbano Lecchese (Si.M.U.L.), Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco

ALESSANDROALBERTO GIACOMETTI MANZONI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... IlPreserver genio che of si the manifesta past and attraverso great innovator l’arte of the Italian language Texts by Card. Gianfranco Ravasi, Gian Luigi Daccò, Emanuele Banfi, Giovanni Orelli, Barbara Cattaneo Preserver of the past and great innovator of the Italian language ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Manzoni: Two spiritual registers Card. Gianfranco Ravasi* Page I: Giuseppe Molteni, Ritratto di Alessandro Manzoni, mid 19th century, oil on canvas, Sistema Museale Urbano Lecchese (Si.M.U.L.), Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. Left: Carlo Preda, Madonna Assunta, first-half 18th century, oil on canvas, Si.M.U.L., Villa Manzoni, chapel, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. On this page: Giovanni Battista Galizzi, I capponi di Renzo, first-half 20th century, India ink and watercolour, Si.M.U.L., Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. Alessandro Manzoni ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... IV Preserver of the past and great innovator of the Italian -

A Mirror on the History of the Foundations of Modern Criminal Law Bernard E

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics Economics 2013 Beccaria's 'On Crimes and Punishments': A Mirror on the History of the Foundations of Modern Criminal Law Bernard E. Harcourt Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/law_and_economics Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Bernard E. Harcourt, "Beccaria's 'On Crimes and Punishments': A Mirror on the History of the Foundations of Modern Criminal Law" (Coase-Sandor Institute for Law & Economics Working Paper No. 648, 2013). This Working Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Coase-Sandor Institute for Law and Economics at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Coase-Sandor Working Paper Series in Law and Economics by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHICAGO COASE-SANDOR INSTITUTE FOR LAW AND ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER NO. 648 (2D SERIES) PUBLIC LAW AND LEGAL THEORY WORKING PAPER NO. 433 BECARRIA’S ON CRIMES AND PUNISHMENTS: A MIRROR ON THE HISTORY OF THE FOUNDATIONS OF MODERN CRIMINAL LAW Bernard E. Harcourt THE LAW SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO July 22, 2013 This paper can be downloaded without charge at the Institute for Law and Economics Working Paper Series: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/Lawecon/index.html and at the Public Law and Legal Theory Working Paper Series: http://www.law.uchicago.edu/academics/publiclaw/index.html and The Social Science Research Network Electronic Paper Collection. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2296605 Beccaria’s On Crimes and Punishments: A Mirror on the History of the Foundations of Modern Criminal Law * * * Bernard E. -

Cesare Beccaria: Utilitarianism, Contractualism and Rights

Cesare Beccaria: Utilitarianism, Contractualism and Rights Mario Ricciardi and Filippo Santoni de Sio If you are visiting Milan, you will discover that ‘Cesare Beccaria’ is a Mila- nese household name. Walking through the streets downtown – in an area fa- miliar to shoppers – is Cesare Beccaria Square, and everyone has heard of the high school, or of the juvenile prison, named after this illustrious citizen of the past. While walking through the square, somebody might even direct your attention to a bronze, a replica of an original Nineteenth century marble by Giuseppe Grandi, which shows a man no longer young, stout; from his clothing and hairstyle he is easily recognisable as a nobleman of the Eighteenth century. He is absorbed in his thoughts – some books are at his feet – suggesting that he must be a scholar, maybe a philosopher. Those asking for further information about the thoughtful man on the pedestal will easily satisfy their curiosity. Even in these forgetful times anybody will tell them that he is Cesare Beccaria, the author of On Crimes and Punishments. This answer exemplifies the phenom- enon of a literary work that almost overwhelms the memory of its author. Ac- cording to Luigi Settembrini, On Crimes and Punishments is more than a book, it is “a fact of history, because it marks the time when torture and atrocities were abolished in criminal trials, and people began to wonder whether it is really necessary to wage death on those guilty of a crime” (1878: 67). For the Neapoli- tan scholar, who wrote in the Nineteenth century, roughly one hundred years after the publication of Beccaria’s book, the phenomenon we have mentioned above is already a fait accompli, inspiring ambiguous praise. -

Monache E Monsignori Nella Progenie Di Alessandro Manzoni

MONS. DANIELE ROTA Inesplorate indicazioni genealogiche Canonico Onorario della Papale Basilica di S. Pietro in Vaticano Monache e Monsignori nella progenie di Alessandro Manzoni La ricerca incompiuta L’approfondimento storico- anagrafi co sulla famiglia di Ales- sandro Manzoni, sia nella compo- nente paterna, come in quella materna dei Beccaria, sembra ben lungi dall’essere concluso. I cento- quarant’anni che ci separano dalla morte sono relativamente pochi per una disamina esauriente non solo della sua multiforme opera, Alessandro Manzoni ma anche del composito contesto (1785-1873) ritratto familiare in cui l’emotivo scrittore da Carlo Gerosa si trovò a vivere. (circa 1835). Milano, Casa del Manzoni. Del resto, se si tiene presen- te che anche taluni aspetti della vita di Dante,1 come pure del Pe- Alessandro Manzoni 2 3 portrayed by Carlo trarca e del Boccaccio, per citare Gerosa (circa 1835). solo autori assai noti, restano an- Milan, Manzoni’s cora in parte problematici, dopo House. parecchi secoli di erudita ricerca, Nuns and Monsignors in the offspring of Alessandro Manzoni The religious spirit which, from the “conversion” onwards, animates the work of Manzoni is no bolt from the blue. Several of his noble ancestors had followed an ecclesiastical career. From the 16th century until almost the whole of the 19th century, it was a compulsory choice for some members of noble families. The accurate descriptions of some characters in his novel, “The Betrothed” come from his direct knowledge of the clerical world. In his dynasty we find a Royal Imperial Chaplain; his uncle Paolo Antonio Ignazio Giuseppe was a monsignor and canon of Milan Cathedral; his aunt Maria Teresa Anselma spent a long period in St. -

Cesare Beccaria's Forgotten Influence on American Law John Bessler University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected]

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2017 The tI alian Enlightenment and the American Revolution: Cesare Beccaria's Forgotten Influence on American Law John Bessler University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the European Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation John Bessler, The Italian Enlightenment and the American Revolution: Cesare Beccaria's Forgotten Influence on American Law, 37 Mitchell Hamline Law Journal of Public Policy and Practice 1 (2017). Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac/972 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ITALIAN ENLIGHTENMENT AND THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION: CESARE BECCARIA’S FORGOTTEN INFLUENCE ON AMERICAN LAW John D. Bessler‡ Abstract The influence of the Italian Enlightenment—the Illuminismo—on the American Revolution has long been neglected. While historians regularly acknowledge the influence of European thinkers such as William Blackstone, John Locke and Montesquieu, Cesare Beccaria’s contributions to the origins and development of American law have largely been forgotten by twenty-first century Americans. In fact, Beccaria’s book, Dei delitti e delle pene (1764), translated into English as On Crimes and Punishments (1767), significantly shaped the views of American revolutionaries and lawmakers.