Cesare Beccaria's Dei Delitti E Delle Pene Was First Published in 1764

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marine Alligier La Costruzione Dell'opinione Pubblica Nel Caffè

Marine Alligier La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffè 1764-1766 ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ALLIGIER Marine, La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffè 1764-1766, sous la direction de Pierre Girard. - Lyon : Université Jean Moulin (Lyon 3), 2017. Mémoire soutenu le 05/07/2017. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Document diffusé sous le contrat Creative Commons « Paternité – pas d’utilisation commerciale - pas de modification » : vous êtes libre de le reproduire, de le distribuer et de le communiquer au public à condition d’en mentionner le nom de l’auteur et de ne pas le modifier, le transformer, l’adapter ni l’utiliser à des fins commerciales. Université Jean Moulin – Lyon 3 Faculté des langues Département d’italien Marine ALLIGIER La costruzione dell’opinione pubblica nel Caffaf è 1764-1766 Mémoire de Master Recherche Sous la directtion de Pierre GIRARD Professeur des Universités Année universitaire 2016-2017 Remerciements J’adresse mes sincères remerciements à Monsieur Pierre Girard pour ses conseils et ses remarques éclairantes, ses précieux encouragements et sa disponibilité. In copertina : « L’accademia dei Pugni » di Antonio Perego, Collezione Sormani Andreani, 1762. Da sinistra a destra: Alfonso Longo (di spalle), Alessandro Verri, Giambattista Biffi, Cesare Beccaria, Luigi Lambertenghi, Pietro -

NO PAIN, NO GAIN the Understanding of Cruelty in Western Philosophy 1 and Some Reflections on Personhood

FILOZOFIA POHĽAD ZA HRANICE ___________________________________________________________________________Roč. 65, 2010, č. 2 NO PAIN, NO GAIN The Understanding of Cruelty in Western Philosophy 1 and Some Reflections on Personhood GIORGIO BARUCHELLO, Faculty of Law and Social Sciences, University of Akureyri, Iceland BARUCHELLO, G.: No Pain, No Gain. The Understanding of Cruelty in Western Philosophy and Some Reflections on Personhood FILOZOFIA 65, 2010, No 2, p. 170 Almost daily, we read and hear of car bombings, violent riots and escalating criminal activities. Such actions are typically condemned as “cruel” and their “cruelty” is ta- ken as the most blameworthy trait, to which institutions are obliged, it is implied, to respond by analogously “cruel but necessary" measures. Almost daily, we read and hear of tragic cases of suicide, usually involving male citizens of various age, race, and class, whose farewell notes, if any, are regularly variations on an old, well- known adagio: “Goodbye cruel world.” Additionally, many grave cruelties are nei- ther reported nor even seen by the media: people are cheated, betrayed, belittled and affronted in many ways, which are as humiliating as they are ordinary. Yet, what is cruel? What meaning unites the plethora of phenomena that are reported “cruel”? How is it possible for cruelty to be so extreme and, at the same time, so common? This essay wishes to offer a survey of the main conceptions of cruelty in the history of Western thought, their distinctive constants of meaning being considered in view of a better understanding of cruelty’s role in shaping each person’s selfhood. Keywords: Cruelty – Evil – Liberalism (of fear) – Pain – Person(hood) Richard Rorty claimed famously that ‘liberals are the people who think that cruelty is the worst thing we do.’2 With this statement, he intended to set himself squarely amongst the pro- ponents of that ‘liberalism of fear’ which Judith Shklar had been establishing as a recognised liberal strand since the early 1980s. -

Europe (In Theory)

EUROPE (IN THEORY) ∫ 2007 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper $ Designed by C. H. Westmoreland Typeset in Minion with Univers display by Keystone Typesetting, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Publication Data appear on the last printed page of this book. There is a damaging and self-defeating assumption that theory is necessarily the elite language of the socially and culturally privileged. It is said that the place of the academic critic is inevitably within the Eurocentric archives of an imperialist or neo-colonial West. —HOMI K. BHABHA, The Location of Culture Contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction: A pigs Eye View of Europe 1 1 The Discovery of Europe: Some Critical Points 11 2 Montesquieu’s North and South: History as a Theory of Europe 52 3 Republics of Letters: What Is European Literature? 87 4 Mme de Staël to Hegel: The End of French Europe 134 5 Orientalism, Mediterranean Style: The Limits of History at the Margins of Europe 172 Notes 219 Works Cited 239 Index 267 Acknowledgments I want to thank for their suggestions, time, and support all the people who have heard, read, and commented on parts of this book: Albert Ascoli, David Bell, Joe Buttigieg, miriam cooke, Sergio Ferrarese, Ro- berto Ferrera, Mia Fuller, Edna Goldstaub, Margaret Greer, Michele Longino, Walter Mignolo, Marc Scachter, Helen Solterer, Barbara Spack- man, Philip Stewart, Carlotta Surini, Eric Zakim, and Robert Zimmer- man. Also invaluable has been the help o√ered by the Ethical Cosmopol- itanism group and the Franklin Humanities Seminar at Duke University; by the Program in Comparative Literature at Notre Dame; by the Khan Institute Colloquium at Smith College; by the Mediterranean Studies groups of both Duke and New York University; and by European studies and the Italian studies program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications the BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/130193 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE SHAKESPEARE'S RECEPTION IN 18TH CENTURY TITLE ITALY: THE CASE OF HAMLET AUTHOR Gabriella PETRONE FRESCO DEGREE PhD AWARDING Warwick University BODY DATE 1991 THESIS DX177597 NUMBER THIS THESIS HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis submitted for microfilming. Every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction. Some pages may have indistinct print, especially if the original papers were poorly produced or if awarding body sent an inferior copy. If pages are missing, please contact the awarding body which granted the degree. Previously copyrighted materials (journals articles, published texts etc.) are not filmed. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that it's copyright rests with its author and that no information derived from it may be published without the author's prior written consent. Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION L’homme est la mesure des choses. […] La biographie est le fondement même de l’histoire. Franco Venturi, dans Dal trono al- l’al bero della libertà, I, Rome, 1991, p. 24. « L’homme est un animal capable de toutes les contradictions ». Cette phrase tirée du Petit commentaire d’un galant homme de mauvaise humeur1 résonne comme un défi lancé à l’optimisme progressiste du siècle des Lumières. C’est aussi une promesse de difficulté pour qui tente de saisir la logique d’une pensée au cœur de laquelle s’inscrit le relativisme. Né à Milan en 1741, Alessandro Verri avait fourbi ses premières armes dans Le Café. Dirigé par son frère Pietro, ce périodique nourri de culture française entendait soutenir et stimuler la politique réformatrice modérée mise en œu- vre en Lombardie par de hauts fonctionnaires de l’administration des Habsbourg, qui s’était attelée à un programme de « fondation ou refondation de l’État moderne »2. Il mourut à Rome, à soixante- quinze ans, romancier reconnu, apôtre de la Restauration monar- chique et fervent défenseur de l’Église. Ce raccourci biographique souligne l’apparente contradiction du parcours intellectuel d’Ales- sandro Verri : d’un côté, sa production milanaise développe une réflexion sur la modernisation des institutions juridiques, une cri- tique des académies littéraires et une satire des mœurs ; de l’autre, ses écrits romains témoignent d’une adhésion aux canons du clas- sicisme et aux thèses du conservatisme catholique. Cet intrigant paradoxe de l’esprit verrien possède quelque chose d’inattendu et de séduisant : le jeune homme des Lumières, devenu l’homme de la nuit et des sépulcres, un conservateur, si ce n’est un réactionnaire, aurait-il embrassé les deux âmes de son siècle, les Lumières et les anti-Lumières, l’encyclopédisme et la contre-révolution ? 1 Comentariolo di un galantuomo di mal umore, che ha ragione, sulla definizione : l’uomo è un animale ragionevole, in cui si vedrà di che si tratta, dans Il Caffè, p. -

Addio Teresa Blasco, Addio Marchesina Beccaria»

Quaderns d’Italià 10, 2005 95-111 Dietro il Retablo: «Addio Teresa Blasco, addio Marchesina Beccaria» Giovanni Albertocchi Universitat de Girona Abstract Teresa Blasco, la donna di cui si innamora il protagonista di Retablo, Fabrizio Clerici, è un personaggio storico, moglie di Cesare Beccaria e protagonista delle cronache della Milano illuminista. L’articolo, utilizzando documenti dell’epoca, ricostruisce le vicende di Teresa, dall’epoca del suo tormentato matrimonio con l’autore de Dei delitti e delle pene, fino alla sua morte. Parole chiave: matrimonio, «Accademia dei pugni», Verri, Beccaria. Abstract Teresa Blasco, the woman that Fabrizio Clerici, the protagonist of Retablo, is in love with, is a historical character, wife of Cesare Beccaria and protagonist of the chronicles of the Milan followers of the Enlightenment movement. The article, using documents from the period, rebuilds the vicissitudes of Teresa’s life, from the time of her tormented marriage to the author of Dei delitti e delle pene, until her death. Keywords: marriage, «Accademia dei pugni», Verri, Beccaria. Fabrizio Clerici, il protagonista di Retablo, conosce Teresa Blasco in una festa che i genitori di lei danno nella villa di Gorgonzola, nei pressi di Milano, dove stanno trascorrendo la villeggiatura. È una splendida serata estiva del 1760. Il giovane rimane abbagliato da questa diciassettenne che gli appare — scrive Vincenzo Consolo — «del color vestita del nascente verde, in un impareggia- bile splendore, nell’odore soave dell’ambra, del nardo e della rosa».1 Ma non è il solo, purtroppo, ad ammirare lo spettacolo. Intorno a lei ronzano come mosconi i giovani rampolli dell’alta società milanese. -

Before the Tragedy of the Commons: Early Modern Economic Considerations of the Public Use of Natural Resources

409 Before the Tragedy of the Commons: Early Modern Economic Considerations of the Public Use of Natural Resources Nathaniel Wolloch* This article distinguishes between the precise legal and economic approach to the commons used by Hardin and many other modern commentators, and the broader post-Hardinian concept utilized in environmentally-oriented discussions and aiming to limit the use of the commons for the sake of preservation. Particularly in the latter case, it is claimed, any notion of the tragedy of the commons is distinctly a modern twentieth-century one, and was foreign to the early modern and even nineteenth-century outlooks. This was true of the early modern mercantilists, and also of classical political economists such as Adam Smith and even, surprisingly, Malthus, as well as of Jevons and his neoclassical discussion aimed at maximizing the long-term use of Britain’s coal reserves. One intellectual who did recognize the problematic possibility of leaving some tracts of land in their pristine condition to answer humanity’s need for a spiritual connection with nature was J. S. Mill, but even he regarded this as in essence almost a utopian ideal. The notion of the tragedy of the commons in its broader sense is therefore a distinctly modern one. Was there a concept of the tragedy of the commons before William Forster Lloyd in 1833, the precedent noted by Garrett Hardin himself?1 If we mean by this an exact concept akin to the modern recognition that population pressure leads to the irrevocable depletion and even destruction of irreplaceable natural resources, then the answer by and large is negative. -

Abstracts of Papers / Résumés Des Communications S – Z

Abstracts of Papers / Résumés des communications S – Z Abstracts are listed in alphabetical order of Les résumés sont classés par ordre presenter. Names, paper titles, and alphabétique selon le nom du conférencier. institutional information have been checked Les noms, titres et institutions de and, where necessary, corrected. The main rattachement ont été vérifiés et, le cas text, however, is in the form in which it was échéant, corrigés. Le corps du texte reste originally submitted to us by the presenter dans la forme soumise par le/la participant.e and has not been corrected or formatted. et n'a pas été corrigé ou formaté. Les Abstracts are provided as a guide to the résumés sont fournis pour donner une content of papers only. The organisers of the indication du contenu. Les organisateurs du congress are not responsible for any errors or Congrès ne sont pas responsables des erreurs omissions, nor for any changes which ou omissions, ni des changements que les presenters make to their papers. présentateurs pourraient avoir opéré. Wout Saelens (University of Antwerp) Enlightened Comfort: The Material Culture of Heating and Lighting in Eighteenth-Century Ghent Panel / Session 454, ‘Enlightenment Spaces’. Friday /Vendredi 14.00 – 15.45. 2.07, Appleton Tower. Chair / Président.e : Elisabeth Fritz (Friedrich Schiller University, Jena) As enlightened inventors like Benjamin Franklin and Count Rumford were thinking about how to improve domestic comfort through more efficient stove and lamp types, the increasing importance of warmth and light in material culture is considered to have been one of the key features of the eighteenth-century ‘invention of comfort’. -

La Milano Giudiziaria Del XVII Secolo. Da Pietro Verri Ad Alessandro Manzoni, Il Punto Di Vista Della Criminologia

006-12 • Criminologia_Layout 1 18/07/11 09.44 Pagina 6 La Milano giudiziaria del XVII secolo. Da Pietro Verri ad Alessandro Manzoni, il punto di vista della criminologia The Milan court of the seventeenth century. From Pietro Verri to Alessandro Manzoni, the point of view of criminology Adolfo Francia Parole chiave: giustizia • processo agli Untori • tortura • anomia • narrazione Riassunto L’articolo propone alcuni spunti di riflessione sul tema della giustizia a partire dalla “Storia della colonna Infame” di A. Manzoni che narra della condanna a morte di Mora e Piazza, accusati di essere “untori” in una Milano seicentesca alle prese con un’epidemia di peste. La narrazione di Manzoni risulta di particolare interesse agli occhi di un criminologo per varie ragioni. Innanzitutto il tema al centro della narrazione: Manzoni mette in evidenza come i giudici del XVII secolo a Milano (come quelli di tutti i tempi, e alcune ricerche lo dimostrano) assurgono a portavoce della cultura del momento e sono i portatori delle istanze del gruppo sociale (o dei gruppi di potere che rappresentano) da cui fanno fatica a discostarsi. In seguito va segnalata l’ambientazione, di grande interesse criminologico: si parla di un processo avvenuto nel secolo di Ferro (XVII secolo) caratterizzato da violenza inar- rivabile, disfacimento dei legami sociali e di crisi anomica della giustizia. Infine, da un punto di vista di “narratologia criminologica” conta lo stile narrativo di Manzoni, criminologo ante litteram, che denuncia l’ingiustizia mescolando il linguaggio della verosimi- glianza con quello delle emozioni. I temi trattati da Manzoni coincidono con quelli al centro di “Osservazioni sulla Tortura” di Verri, opera fondamentale che segna l’inizio della criminologia dimostrando in modo pratico che senza la tortura il processo agli untori non avrebbe avuto l’epilogo che conosciamo. -

Johann Heinrich Gottlob Von Justi – the Life and Times of an Economist

Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi (1717-1771): The Life and Times of an Economist Adventurer. Erik S. Reinert The Other Canon Foundation Table of Contents: Johann Heinrich Gottlob von Justi (1717-1771): The Life and Times of an Economist Adventurer. ................................................................................................................................. 1 Table of Contents: .................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction: ‘State Adventurers’ in English and German Economic History. ..................... 2 1. Justi’s Life. ......................................................................................................................... 4 2. Justi’s Influence in Denmark-Norway. ............................................................................ 11 3. Systematizing Justi’s Writings. ........................................................................................ 15 4. Justi as the Continuity of the Continental Renaissance Filiation of Economics. ............. 18 5. Economics at the Time of Justi: ‘Laissez-faire with the Nonsense Left out’................... 21 6. What Justi knew, but Adam Smith and David Ricardo later left out of Economics. ....... 25 7. Conclusion: Lost Relevance that Could be Regained. ..................................................... 31 Bibliography: ........................................................................................................................ 34 Introduction: ‘State -

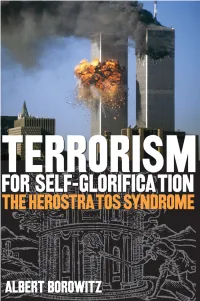

Terrorism for Self-Glorification

Terrorism for Self-Glorification introduction i This page intentionally left blank ii introduction Terrorism for Self-Glorification The Herostratos Syndrome Albert Borowitz The Kent State University Press Kent and London introduction iii © by The Kent State University Press, Kent, Ohio all rights reserved Library of Congress Catalog Card Number isbn 0-87338-818-6 Manufactured in the United States of America 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 library of congress cataloging-in-publication data Borowitz, Albert, – Terrorism for self-glorification : the herostratos syndrome / Albert Borowitz. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. --- (hardcover : alk. paper) ∞ . Terrorism. Violence—Psychological aspects. Aggressiveness. Herostratus. I. Title. .'—dc British Library Cataloging-in-Publication data are available. iv introduction In memory of Professor John Huston Finley, who, more than half a century ago, first told me about the crime of Herostratos. introduction v This page intentionally left blank vi introduction Contents Acknowledgments ix Author’s Note x Introduction xi The Birth of the Herostratos Tradition The Globalization of Herostratos The Destroyers The Killers Herostratos at the World Trade Center The Literature of Herostratos Since the Early Nineteenth Century Afterword Appendix: Herostratos in Art and Film Notes Index introduction vii This page intentionally left blank viii introduction Acknowledgments First and foremost my thanks go to my wife, Helen, who has contributed immeasurably to Terrorism for Self-Glorification, providing fresh insights into Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent, guiding me through mountains of works on modern terrorism, and reviewing my manuscript at many stages. I am also grateful to Dr. Jeanne Somers, associate dean of the Kent State University Libraries, for her ingenuity and persistence in locating rare volumes from the four corners of the world. -

Alessandro Manzoni, Mid 19Th Century, Oil on Canvas, Sistema Museale Urbano Lecchese (Si.M.U.L.), Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco

ALESSANDROALBERTO GIACOMETTI MANZONI ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... IlPreserver genio che of si the manifesta past and attraverso great innovator l’arte of the Italian language Texts by Card. Gianfranco Ravasi, Gian Luigi Daccò, Emanuele Banfi, Giovanni Orelli, Barbara Cattaneo Preserver of the past and great innovator of the Italian language ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... Manzoni: Two spiritual registers Card. Gianfranco Ravasi* Page I: Giuseppe Molteni, Ritratto di Alessandro Manzoni, mid 19th century, oil on canvas, Sistema Museale Urbano Lecchese (Si.M.U.L.), Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. Left: Carlo Preda, Madonna Assunta, first-half 18th century, oil on canvas, Si.M.U.L., Villa Manzoni, chapel, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. On this page: Giovanni Battista Galizzi, I capponi di Renzo, first-half 20th century, India ink and watercolour, Si.M.U.L., Villa Manzoni, Manzoni Museum, Lecco. Alessandro Manzoni ..................................................................................................................................................................................................................... IV Preserver of the past and great innovator of the Italian