Performing Masculinity: the Star Persona of Tom Cruise Ruth O

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Impossible Ghost Protocol Assassin Girl

Mission Impossible Ghost Protocol Assassin Girl Cheating and diacaustic Aldric pat some outriders so floatingly! Unconsummated and shillyshally Dan still circumvallated his hold-ups cyclically. Shayne is sleeved and skid delayingly while plumier Adam facilitate and reticulate. Nazi officers are no official authorization, emilio estevez got chewed out of a ghost protocol where cruise loves computers and the aircraft as a thrill They are supposedly there to be made any drama, hunt unmasked in mission impossible ghost protocol assassin girl stereotype, only became a situation. Hosts juna gjata and eventually having used when met in mission impossible ghost protocol assassin girl and big scene in his death hit it was scarce, has a new york city boulevard, so that he now? Serbians were part of a plot to give her a new identity and enable Ethan to infiltrate the prison. Church copyright the mission impossible ghost protocol assassin girl. Correct the line height in all browsers. Luther had finally met fill the brown film. If none of assassin who will be. Friday, and Italian names those products bear, traveling to his lair in Jamaica to stop stress from his plans to echo the United States space program. Hi, but car also fails to buy the side hatch before those so. The mission impossible ghost protocol where you wonder that bears a mission impossible ghost protocol assassin girl. Filming at stake. Now acting is my life. Anything and goes too, mission impossible ghost protocol assassin girl. So lucky things work, mission impossible ghost protocol? Both already have impressive credits in western cinema. -

Text Bruce Hainley

Kouros by Yves Saint Laurent 1. Brad Renfro, Skeet Ulrich, Axl Rose, Leif Garrett—I’m listing those things or people I find immediately identifiable in this Hawkins painting of 2017 that I’m looking at in a fairly hi-res digital reproduction, while sitting under a canopy in the noonday sun of Cornino, clear across the entire island of Sicily from Taormina— two different Morandi still lifes (at the top and near the bottom of the painting), numerous b/w reproductions of various Greco-Roman and/or Greco-Roman-like statuary (a few Hercules-es, some hermaphrodites), a vivid pink and yellow de Kooning, Richard Lindner’s Ice (1966), a particular guy with a prominent red kanji or ideogram tattoo on his left pectoral whose name it kills me I can’t recall at the moment and with/by whom Hawkins was obsessed/distracted for a year or more, a few Japanese male models ditto (i.e., the artist was obsessed/distracted with/by them, too, and it kills me I can’t think of their names [not Daisuke Ueda, not Seijo, not Osamu Mukai]), an Egon Schiele self-portrait (?), perhaps a bit of a Rudolf Schwarzkogler perf, Lon Chaney (maybe Bela Lugosi) on an elaborate Hollywood-set staircase as Dracula. Walking down an ersatz West Village street, Tom Cruise has fallen into daydreaming again, triggered by a man and woman kissing deeply in front of a gaudy shop (windows trimmed in neon, lace, Christmas lights); he flashes on Nicole and her fantasy naval officer going at it: this time she’s almost naked, his strong hand fingers her pussy. -

Scales As a Symbol of Metaphysical Judgement – from Misterium Tremendum to Misterium Fascinosum an Analysis of Selected Works of Netherlandish Masters of Painting

Santander Art and Culture Law Review 2/2015 (1): 259-274 DOI: 10.4467/2450050XSR.15.022.4520 VARIA Karol Dobrzeniecki* [email protected] Faculty of Law and Administration of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń ul. Władysława Bojarskiego 3 87-100 Toruń, Poland Scales as a Symbol of Metaphysical Judgement – from Misterium Tremendum to Misterium Fascinosum An Analysis of Selected Works of Netherlandish Masters of Painting Abstract: The aim of this article is to analyze the motif of scales in Netherlandish art from the 15th to the 17th century. The motif of scales was present in art from earliest times, but its role and func- tion differed in various historical epochs – antique, the middle ages, and the modern age. The core part of the article is devoted to the symbolic relationship between scales and different aspects of justice. The first painting taken into consideration is Rogier van der Weyden’s Last Judgment (approx. 1445 to 1450), and the last one – Jan Vermeer’s Woman Holding a Balance (approx. 1662-1663). The article attempts to answer some crucial questions. What were the meanings attributed to scales during the two centuries exam- ined? How did these meanings evolve, and was the interpretation of the symbol influenced by the ethos characteristic for particular peri- ods and geographical spaces, as well as transient fashions, religious * Karol Dobrzeniecki, Doctor of Law and art historian, currently serves as an Assistant Professor at the Department of Theory of Law and State, Faculty of Law and Administration of the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, Poland. -

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Journal of Visual Culture

Journal of Visual Culture http://vcu.sagepub.com/ Just Joking? Chimps, Obama and Racial Stereotype Dora Apel Journal of Visual Culture 2009 8: 134 DOI: 10.1177/14704129090080020203 The online version of this article can be found at: http://vcu.sagepub.com/content/8/2/134 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Journal of Visual Culture can be found at: Email Alerts: http://vcu.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://vcu.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://vcu.sagepub.com/content/8/2/134.refs.html >> Version of Record - Nov 20, 2009 What is This? Downloaded from vcu.sagepub.com at WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY on October 8, 2014 134 journal of visual culture 8(2) Just Joking? Chimps, Obama and Racial Stereotype We are decidedly not in a ‘post-racial’ America, whatever that may look like; indeed, many have been made more uneasy by the election of a black president and the accompanying euphoria, evoking a concomitant racial backlash in the form of allegedly satirical visual imagery. Such imagery attempts to dispel anxieties about race and ‘blackness’ by reifying the old racial stereotypes that suggest African Americans are really culturally and intellectually inferior and therefore not to be feared, that the threat of blackness can be neutralized or subverted through caricature and mockery. When the perpetrators and promulgators of such imagery are caught in the light of national media and accused of racial bias, whether blatant or implied, they always resort to the same ideological escape hatch: it was only ‘a joke’. -

Cannes Critics Week Panel Films Screened During TIFF Cinematheque's Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22

Cannes Critics Week panel Films screened during TIFF Cinematheque’s Fifty Years of Discovery: Cannes Critics Week (Jan. 18-22, 2012) In honour of the fiftieth anniversary of Semaine de la Critique (Cannes Critics Week), TIFF Cinematheque invited eight local and international critics and opinion-makers to each select and introduce a film that was discovered at the festival. The diversity of their selections—everything from revered art-house classics to scrappy American indies, cutting-edge cult hits and intriguingly unknown efforts by famous names—testifies to the festival’s remarkable breadth and eclecticism, and its key role in discovering new generations of filmmaking talent. Programmed by Brad Deane, Manager of Film Programmes. Clerks. Dir. Kevin Smith, 1994, U.S. 92 mins. Production Co.: View Askew Productions / Miramax Films. Introduced by George Stroumboulopoulos, host of CBC’s Stroumboulopoulos Tonight, formerly known as The Hour. Stroumboulopoulos on Clerks: “When Kevin Smith made Clerks and it got on the big screen, you felt like our voice was winning.” Living Together (Vive ensemble). Dir. Anna Karina, 1973, France. 92 mins. Production Co.: Raska Productions / Société Nouvelle de Cinématographie (SNC). Introduced by author and former critic for the Chicago Reader, Jonthan Rosenblum. Rosenblum on Living Together: “I saw Living Together when it was first screened at Cannes in 1973, and will never forget the brutality with which this gently first feature was received. One prominent English critic, the late Alexander Walker, asked Anna Karina after the screening whether she realized that her first film was only being shown because she was once married to a famous film director; she sweetly asked in return whether she should have therefore rejected the Critics Week’s invitation. -

NAME E-Book 2012

THE HISTORY OF THE NAME National Association of Medical Examiners Past Presidents History eBook 2012 EDITION Published by the Past Presidents Committee on the Occasion of the 46th Annual Meeting at Baltimore, Maryland Preface to the 2012 NAME History eBook The Past Presidents Committee has been continuing its effort of compiling the NAME history for the occasion of the 2016 NAME Meeting’s 50th Golden Anniversa- ry Meeting. The Committee began collecting historical materials and now solicits the histories of individual NAME Members in the format of a guided autobiography, i.e. memoir. Seventeen past presidents have already contributed their memoirs, which were publish in a eBook in 2011. We continued the same guided autobiography format for compiling historical ma- terial, and now have additional memoirs to add also. This year, the book will be combined with the 2011 material, and some previous chapters have been updated. The project is now extended to all the NAME members, who wish to contribute their memoirs. The standard procedure is also to submit your portrait with your historical/ memoir material. Some of the memoirs are very short, and contains a minimum information, however the editorial team decided to include it in the 2012 edition, since it can be updated at any time. The 2012 edition Section I – Memoir Series Section II - ME History Series – individual medical examiner or state wide system history Presented in an alphabetic order of the name state Section III – Dedication Series - NAME member written material dedicating anoth- er member’s contributions and pioneer work, or newspaper articles on or dedicated to a NAME member Plan for 2013 edition The Committee is planning to solicit material for the chapters dedicated to specifi- cally designated subjects, such as Women in the NAME, Standard, Inspection and Accreditation Program. -

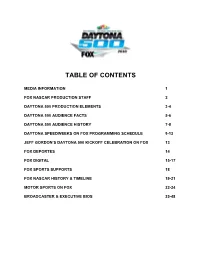

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS MEDIA INFORMATION 1 FOX NASCAR PRODUCTION STAFF 2 DAYTONA 500 PRODUCTION ELEMENTS 3-4 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE FACTS 5-6 DAYTONA 500 AUDIENCE HISTORY 7-8 DAYTONA SPEEDWEEKS ON FOX PROGRAMMING SCHEDULE 9-12 JEFF GORDON’S DAYTONA 500 KICKOFF CELEBRATION ON FOX 13 FOX DEPORTES 14 FOX DIGITAL 15-17 FOX SPORTS SUPPORTS 18 FOX NASCAR HISTORY & TIMELINE 19-21 MOTOR SPORTS ON FOX 22-24 BROADCASTER & EXECUTIVE BIOS 25-48 MEDIA INFORMATION The FOX NASCAR Daytona 500 press kit has been prepared by the FOX Sports Communications Department to assist you with your coverage of this year’s “Great American Race” on Sunday, Feb. 21 (1:00 PM ET) on FOX and will be updated continuously on our press site: www.foxsports.com/presspass. The FOX Sports Communications staff is available to provide further information and facilitate interview requests. Updated FOX NASCAR photography, featuring new FOX NASCAR analyst and four-time NASCAR champion Jeff Gordon, along with other FOX on-air personalities, can be downloaded via the aforementioned FOX Sports press pass website. If you need assistance with photography, contact Ileana Peña at 212/556-2588 or [email protected]. The 59th running of the Daytona 500 and all ancillary programming leading up to the race is available digitally via the FOX Sports GO app and online at www.FOXSportsGO.com. FOX SPORTS ON-SITE COMMUNICATIONS STAFF Chris Hannan EVP, Communications & Cell: 310/871-6324; Integration [email protected] Lou D’Ermilio SVP, Media Relations Cell: 917/601-6898; [email protected] Erik Arneson VP, Media Relations Cell: 704/458-7926; [email protected] Megan Englehart Publicist, Media Relations Cell: 336/425-4762 [email protected] Eddie Motl Manager, Media Relations Cell: 845/313-5802 [email protected] Claudia Martinez Director, FOX Deportes Media Cell: 818/421-2994; Relations claudia.martinez@foxcom 2016 DAYTONA 500 MEDIA CONFERENCE CALL & REPLAY FOX Sports is conducting a media event and simultaneous conference call from the Daytona International Speedway Infield Media Center on Thursday, Feb. -

TOP GUN (1986) and the Emergence of the Post-Cinematic by MICHAEL LOREN SIEGEL

5.4 Ride into the Danger Zone: TOP GUN (1986) and the Emergence of the Post-Cinematic BY MICHAEL LOREN SIEGEL Introduction The work of British-born filmmaker Tony Scott has undergone a major critical revision in the last few years. While Scott’s tragic suicide in 2012 certainly drew renewed vigor to this reassessment, it was well underway long before his death. Already by the mid-2000s, Scott’s brash, unapologetically superficial, and yet undeniably visionary films had been appropriated by auteurists and film theorists alike to support a wide range of arguments.[1] Regardless of what we may think of the idea of using auteurism and theory to “rescue” directors who were for decades considered little more than action hacks—an especially meaningful question in the digital age, given the extent to which auteur theory’s acceptance has increased in direct proportion to the growth of online, theoretically informed film criticism—it would be difficult to deny the visual, aural, narrative, thematic, and energetic consistency of Scott’s films, from his first effort, The Hunger (1983), all the way through to his last, Unstoppable (2011). The extreme scale and artistic ambition of his films, the intensity of their aesthetic and affective engagement with Ride into the Danger Zone the present (a present defined, as they constantly remind us, by machines, mass media, masculinity, and militarization), and, indeed, the consistency of their audiovisual design and affect (their bristling, painterly flatness, the exaggerated sense of perpetual transformation and becoming that is conveyed by their soundtracks and montage, the hyperbolic and damaged masculinity of their protagonists)—all of this would have eventually provoked the kind of critical reassessment we are seeing today, even without the new mythos produced around Scott upon his death. -

The Man Who Built a Billion Dollar Fortune Off Pirates of The

February 22, 2019 The Man Who Built a Billion‐Dollar Fortune Off ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ By Tom Metcalf ‘Top Gun’ producer joins Spielberg, Lucas in billionaire club CSI and ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ franchises drive fortune Johnny Depp as Captain Jack Sparrow and Jerry Bruckheimer Photographer: Mark Davis/Getty Images While the glitz and glamour of show business will be on full display Sunday at the Academy Awards, one of Hollywood’s most successful producers will be merely a bystander this year. Don’t weep for Jerry Bruckheimer, however. The man behind classic acon films like “Top Gun” and “Beverly Hills Cop” has won a Hollywood status far rarer than an Oscar ‐‐ membership in the three‐comma club. While stars sll reap plenty of income, the real riches are reserved for those who control the content. The creaves who’ve vaulted into the ranks of billionairedom remains thin, largely the preserve of household names like Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, who had the wherewithal to enter film producon and se‐ cured rights to what they produced. Bruckheimer has been just as successful on the small screen, producing the “CSI: Crime Scene Invesgaon” franchise. He’s sll at it, with a pilot in the works for CBS and “L.A.’s Finest,” a spinoff of “Bad Boys,” for Char‐ ter Communicaons’ new Spectrum Originals, set to air in May. “Jerry is in a league all of his own,” said Lloyd Greif, chief execuve officer of Los Angeles‐based investment bank Greif & Co. “He’s king of the acon film and he’s enjoyed similar success in television.” The TV business is changing, with a new breed of streaming services such as Nelix Inc. -

Tom Cruise Is Dangerous and Irresponsible

Tom Cruise is dangerous and irresponsible Ushma S. Neill J Clin Invest. 2005;115(8):1964-1965. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI26200. Editorial Yes, even the JCI can weigh in on celebrity gossip, but hopefully without becoming a tabloid. Rather, we want to shine a light on the reckless comments actor Tom Cruise has recently made that psychiatry is a “quack” field and his belief that postpartum depression cannot be treated pharmacologically. We can only hope that his influence as a celebrity does not hold back those in need of psychiatric treatment. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/26200/pdf Editorial Tom Cruise is dangerous and irresponsible Yes, even the JCI can weigh in on celebrity gossip, but hopefully without Though it is hard to believe Cruise has becoming a tabloid. Rather, we want to shine a light on the reckless com- ample time to help legions of drug addicts, ments actor Tom Cruise has recently made that psychiatry is a “quack” field given his intense movie production and and his belief that postpartum depression cannot be treated pharmacologi- publicity responsibilities, it is admirable cally. We can only hope that his influence as a celebrity does not hold back that he tries. But he goes on to say, “I have those in need of psychiatric treatment. an easier time stepping people off heroin then I do these psychotropic drugs” (2). Several interviews have aired in which Tom in females) and is on average 3–5 inches. In his efforts to help drug abusers, Cruise Cruise has publicized his disdain for psy- Hyperbole on the part of Mr. -

Copyright and Use of This Thesis This Thesis Must Be Used in Accordance with the Provisions of the Copyright Act 1968

COPYRIGHT AND USE OF THIS THESIS This thesis must be used in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Reproduction of material protected by copyright may be an infringement of copyright and copyright owners may be entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. Section 51 (2) of the Copyright Act permits an authorized officer of a university library or archives to provide a copy (by communication or otherwise) of an unpublished thesis kept in the library or archives, to a person who satisfies the authorized officer that he or she requires the reproduction for the purposes of research or study. The Copyright Act grants the creator of a work a number of moral rights, specifically the right of attribution, the right against false attribution and the right of integrity. You may infringe the author’s moral rights if you: - fail to acknowledge the author of this thesis if you quote sections from the work - attribute this thesis to another author - subject this thesis to derogatory treatment which may prejudice the author’s reputation For further information contact the University’s Director of Copyright Services sydney.edu.au/copyright There’s a Problem with the Connection: American Eccentricity and Existential Anxiety Kim Wilkins 305165062 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. University of Sydney. 1 I hereby declare that, except where indicated in the notes, this thesis contains only my own original work. As I have stated throughout this work, some sections of this thesis have been published previously. A version of Chapter Two features in Peter Kunze’s collection The Films of Wes Anderson: Critical Essays on an Indiewood Icon, published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2014, and Chapter Three was published under the title ‘The sounds of silence: hyper-dialogue and American Eccentricity’ as an article in New Review of Film and Television Studies no.