Downloaded from SOAS Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIBRARY ROUTE Indlela Yamathala Eencwadi Boland Control Area Geographic and Demographic Overview

THE LIBRARY ROUTE Indlela yamathala eencwadi Boland Control Area geographic and demographic overview Following up on our series, Insider’s View, in which six library depots and one Wheelie readers were introduced to the staff of the West- Wagon in the area. ern Cape Provincial Library Service and all its ac- By the end of December 2010 the tivities and functions, we are embarking on a new total book stock at libraries in the region series, The library route, in which the 336 libraries amounted to 322 430 items. that feed readers’ needs will be introduced. The area served is diverse and ranges We start the series off with the libraries in from well-known coastal towns to inland the Boland Control Area and as background we towns in the Western Cape. publish a breakdown of the libraries in the various Service points municipalities. Overstrand Municipality libraries Gansbaai STEVEN ANDRIES Hangklip Hawston Assistant Director Chief Library Assistant Moreen September who is Hermanus Steven’s right-hand woman Kleinmond Introduction Mount Pleasant Stanford The Western Cape Provincial Library Service: Zwelihle Regional Organisation is divided into three Theewaterskloof Municipality libraries control areas: Boland, Metropole and Outeni- Worcester and Vanrhynsdorp region from Vanrhynsdorp. Caledon qua. Each control area consists of fi ve regional Genadendal libraries and is headed by an assistant director The staff complement for each region in the Boland control area consists normally of Grabouw and supported by a chief library assistant. Greyton The fi ve regional offi ces in the Boland con- a regional librarian, two library assistants, a driver and a general assistant. -

GTAC/CBPEP/ EU Project on Employment-Intensive Rural Land Reform in South Africa: Policies, Programmes and Capacities

GTAC/CBPEP/ EU project on employment-intensive rural land reform in South Africa: policies, programmes and capacities Municipal case study Matzikama Local Municipality, Western Cape David Mayson, Rick de Satgé and Ivor Manuel with Bruno Losch Phuhlisani NPC March 2020 Abbreviations and acronyms BEE Black Economic Empowerment CASP Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme CAWH Community Animal Health Worker CEO Chief Executive Officer CPA Communal Property of Association CPAC Commodity Project Allocation Committee DAAC District Agri-Park Advisory Committee DAPOTT District Agri Park Operational Task Team DoA Department of Agriculture DRDLR Department of Rural Development and Land Reform DWS Department of Water and Sanitation ECPA Ebenhaeser CPA FALA Financial Assistance Land FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation FPSU Farmer Production Support Unit FTE Full-Time Equivalent GGP Gross Geographic Product GDP Gross Domestic Product GVA Gross Value Added HDI Historically Disadvantaged Individual IDP Integrated Development Plan ILO International Labour Organisation LED Local economic development LORWUA Lower Olifants Water Users Association LSU Large stock units NDP National Development Plan PDOA Provincial Department of Agriculture PGWC Provincial Government of the Western Cape PLAS Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy SDF Spatial Development Framework SLAG Settlement and Land Acquisition Grant SSU Small stock unit SPP Surplus People Project TRANCRAA Transformation of Certain Rural Areas Act WUA Water Users Association ii Table of Contents -

Download This PDF File

Bothalia 41,1: 1–40 (2011) Systematics and biology of the African genus Ferraria (Iridaceae: Irideae) P . GOLDBLATT* and J .C . MANNING** Keywords: Ferraria Burm . ex Mill ., floral biology, Iridaceae, new species, taxonomy, tropical Africa, winter rainfall southern Africa ABSTRACT Following field and herbarium investigation of the subequatorial African and mainly western southern African Ferraria Burm . ex Mill . (Iridaceae: Iridoideae), a genus of cormous geophytes, we recognize 18 species, eight more than were included in the 1979 account of the genus by M .P . de Vos . One of these, F. ovata, based on Moraea ovata Thunb . (1800), was only discovered to be a species of Ferraria in 2001, and three more are the result of our different view of De Vos’s taxonomy . In tropical Africa, F. glutinosa is recircumscribed to include only mid- to late summer-flowering plants, usually with a single basal leaf and with purple to brown flowers often marked with yellow . A second summer-flowering species,F. candelabrum, includes taller plants with several basal leaves . Spring and early summer-flowering plants lacking foliage leaves and with yellow flowers from central Africa are referred toF. spithamea or F. welwitschii respectively . The remaining species are restricted to western southern Africa, an area of winter rainfall and summer drought . We rec- ognize three new species: F. flavaand F. ornata from the sandveld of coastal Namaqualand, and F. parva, which has among the smallest flowers in the genus and is restricted to the Western Cape coastal plain between Ganzekraal and Langrietvlei near Hopefield . Ferraria ornata blooms in May and June in response to the first rains of the season . -

Desktop Assessment

PALAEONTOLOGICAL SPECIALIST STUDY: DESKTOP ASSESSMENT Proposed Maskam limestone mine near Vanrhynsdorp, Matzikama Municipality, Western Cape Province John E. Almond PhD (Cantab.) Natura Viva cc, PO Box 12410 Mill Street, Cape Town 8010, RSA [email protected] August 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Cape Lime (Pty) Ltd, Vredendal, is proposing to develop a high grade limestone mine on the Remainder of the farm Welverdiend 511, some 8 km SSW of Vanrhynsdorp in the Matsikama Municipality, Western Cape Province. No processing plant will be located on site and all excavated limestone material will be transported to the applicant’s existing plant at their Vredendal site some 12 km away. The study area is largely mantled by a range of Late Caenozoic superficial deposits (wind-blown sands, soils, alluvium) that are up to 2m thick and all of low palaeontological sensitivity. The underlying Late Precambrian bedrocks of the Gifberg Group, notably the carbonate target rocks of the Widouw Formation, are metamorphosed, recrysallised and highly deformed, and hence unlikely to contain any fossils. The overall impact significance of the proposed mining development is inferred to be LOW because most of the study area is mantled by superficial sediments of low palaeontological sensitivity and the Precambrian bedrocks are almost certainly unfossiliferous. No further specialist studies or mitigation regarding fossil heritage are considered necessary for this project. Should substantial fossil remains (e.g. vertebrate teeth, bones, petrified wood, stromatolites, shells, trace fossils) be exposed during mining, however, the ECO should safeguard these, preferably in situ, and alert Heritage Western Cape as soon as possible so that appropriate action (e.g. -

WC011 Matzikama Annual Report 2016-17.Pdf

1 DRAFT Annual Report 2016/17 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 ............................................................................................. 4 3.9 COMPONENT D: COMMUNITY AND SOCIAL SERVICES ........................... 80 Component A: Mayor’s Foreword .................................................. 4 3.9.1 Libraries .......................................................................... 80 COMPONENT B: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................... 6 3.9.2 Cemeteries ..................................................................... 83 1.1 Municipal Manager’s Overview ........................................ 6 3.9.3 Child Care, Aged Care and Social Programmes ............... 84 1.2 Municipal Overview ......................................................... 8 3.10 COMPONENT E: ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION .................................. 85 1.3 Service Delivery Overview .............................................. 13 3.11 COMPONENT F: SECURITY AND SAFETY ............................................. 86 1.4 Financial Health Overview .............................................. 14 3.11.1 Traffic Services and Law Enforcement ............................ 86 1.5 Organizational Development Overview ......................... 15 3.11.2 Fire and Disaster Management ...................................... 89 1.6 Audit Outcomes ............................................................. 15 3.12 COMPONENT G: SPORT AND RECREATION ......................................... 89 1.7 2016/17 IDP/Budget -

Flower Route Map 2017

K o n k i e p en w R31 Lö Narubis Vredeshoop Gawachub R360 Grünau Karasburg Rosh Pinah R360 Ariamsvlei R32 e N14 ng Ora N10 Upington N10 IAi-IAis/Richtersveld Transfrontier Park Augrabies N14 e g Keimoes Kuboes n a Oranjemund r Flower Hotlines O H a ib R359 Holgat Kakamas Alexander Bay Nababeep N14 Nature Reserve R358 Groblershoop N8 N8 Or a For up-to-date information on where to see the Vioolsdrif nge H R27 VIEWING TIPS best owers, please call: Eksteenfontein a r t e b e e Namakwa +27 (0)72 760 6019 N7 i s Pella t Lekkersing t Brak u Weskus +27 (0)63 724 6203 o N10 Pofadder S R383 R383 Aggeneys Flower Hour i R382 Kenhardt To view the owers at their best, choose the hottest Steinkopf R363 Port Nolloth N14 Marydale time of the day, which is from 11h00 to 15h00. It’s the s in extended ower power hour. Respect the ower Tu McDougall’s Bay paradise: Walk with care and don’t trample plants R358 unnecessarily. Please don’t pick any buds, bulbs or N10 specimens, nor disturb any sensitive dune areas. Concordia R361 R355 Nababeep Okiep DISTANCE TABLE Prieska Goegap Nature Reserve Sun Run fels Molyneux Buf R355 Springbok R27 The owers always face the sun. Try and drive towards Nature Reserve Grootmis R355 the sun to enjoy nature’s dazzling display. When viewing Kleinzee Naries i R357 i owers on foot, stand with the sun behind your back. R361 Copperton Certain owers don’t open when it’s overcast. -

Die Biblioteekroete I Ndlela Yamathala Eencwadi Verken Vanrhynsdorp- Streek

DIE BIBLIOTEEKROETE I ndlela yamathala eencwadi Verken Vanrhynsdorp- Streek Saamgestel deur ELZA DU PREEZ Leipoldt-Nortier Biblioteek klem op verantwoordelike eienaarskap laat Streekbibliotekaris, Vanrhynsdorpstreek val het. Dié geskiedkundige biblioteek, sentraal geleë Personeel: een bibliotekaris; een biblioteek- Mens ry al met die N7 langs vanuit in die hoofstraat van Clanwilliam, is op 11 assistent; een skoonmaker. Kaapstad, deur die Swartland en Oktober 1958 geopen. Dit is vernoem ’n oor die Piekenierskloofpas tot na twee boesemvriende, dokter C Louis Ledetal: 845 by die afdraai na Citrusdal, die poort na Leipoldt en dokter Le’Fras Nortier. Met die Sirkulasie: 35,050 Vanrhynsdorpstreek, in die noordwestelike onlangse opknapping van die vooraansig uithoek van die Wes-Kaap. Die pad kronkel van die biblioteek is die borsbeelde van verder langs die Olifantsrivier. Aan die dié boesemvriende tot hul vroeëre glorie Citrusdal Biblioteek eenkant lê die Sandveld en Weskus-dorpies herstel. Die vars, nuwe voorkoms van die Citrusdal, waar die Cederberge sierlik pryk, en aan die anderkant die Cederberg Wil- biblioteek verwelkom nie net die inwoners is lemoenwêreld. In die winter het die dernisgebied. Noord van Vanrhynsdorp (op van Clanwilliam nie, maar ook mense van die manjifieke Sneeukop in kapoktyd sy wit die N7 na Namibië) spoed die pad tussen- omliggende dorpe en plase. kappie op. Dienste word gelewer vanuit die deur die wit Knersvlakte-klippies en velerlei Dit is die eerste biblioteek in die munisi- Citrusdal en TP Meyer-biblioteke. vetplantjies tot by die Noord-Kaap-grens paliteit wat ten volle gerekenariseer het. Citrusdal Biblioteek, wat deel vorm van anderkant Bitterfontein met sy omdraai- Gedurende November 2011 is daar van die munisipale kompleks, word druk besoek trein. -

Western Cape Financial and Production Statistics

Census of Agriculture Provincial Statistics 2002- Western Cape Financial and production statistics Report No. 11-02-02 (2002) Department of Agriculture Statistics South Africa i Published by Statistics South Africa, Private Bag X44, Pretoria 0001 © Statistics South Africa, 2006 Users may apply or process this data, provided Statistics South Africa (Stats SA) is acknowledged as the original source of the data; that it is specified that the application and/or analysis is the result of the user's independent processing of the data; and that neither the basic data nor any reprocessed version or application thereof may be sold or offered for sale in any form whatsoever without prior permission from Stats SA. Stats SA Library Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) Data Census of agriculture Provincial Statistics 2002: Western Cape / Statistics South Africa, Pretoria, Statistics South Africa, 2006 XXX p. (Report No. 11-02-02 (2002)). ISBN 0-621-36446-0 1. Agriculture I. Statistics South Africa (LCSH 16) A complete set of Stats SA publications is available at Stats SA Library and the following libraries: National Library of South Africa, Pretoria Division Eastern Cape Library Services, King William’s Town National Library of South Africa, Cape Town Division Central Regional Library, Polokwane Library of Parliament, Cape Town Central Reference Library, Nelspruit Bloemfontein Public Library Central Reference Collection, Kimberley Natal Society Library, Pietermaritzburg Central Reference Library, Mmabatho Johannesburg Public Library This report is available -

West Coast District Municipality West Coast District Municipality Strives Towards Rendering a Dynamic and Effective Service to the Community Under Its Jurisdiction

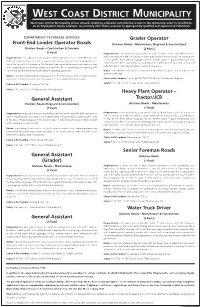

WEST COAST DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY West Coast District Municipality strives towards rendering a dynamic and effective service to the community under its jurisdiction. As an Employment Equity employer, we currently offer these vacancies to appropriately qualified and experienced individuals: DEPARTMENT: TECHNICAL SERVICES Grader Operator Front-End Loader Operator Roads Division: Roads – Maintenance (Regravel & Construction) Division: Roads – Construction & Concrete (2 Posts) (1 Post) Requirements: • the ability to read and write • a code EC drivers licence with PDP • basic life skills • attention to detail • the ability to work independently • must be able to communicate Requirements: • the ability to read and write • Code EC Drivers licence with PDP • basic life in two of the three official languages of the Western Cape • good interpersonal and skills • attention to detail • be able to work independently • must be able to communicate in communication skills • supervisory and reporting skills • good machine operating, writing and two of the three official languages of the Western Cape • good interpersonal and communication technical skills • 1 year relevant grader operating experience. skills • good machine operating, writing and technical skills • supervisory and reporting skills • 6 months relevant front-end loader/machine operating experience. Duties: • performing tasks/activities associated in operating the grader and to supervise the workers in the team. Duties: • performing tasks/activities associated with the driving of the front-end -

Simplified Geological Map of the Republic of South

16° 18° 20° 22° 24° 26° 28° 30° 32° D O I SEDIMENTARY AND VOLCANIC ROCKS INTRUSIVE ROCKS N A R a O R E E E P M . Z I M B A B W E u C Sand, gravel, I SANDVELD (%s); Q %-s O 1.8 alluvium, colluvium, Z BREDASDORP (%b); y calcrete, silcrete Text r %k O KALAHARI a ALGOA (%a); i N t r E MAPUTALAND (%m) e C T SIMPLIFIED GEOLOGICAL MAP 65 . t UITENHAGE (J-Ku); ZULULAND (Kz); SUTHERLAND (Ksu); e r C Malvernia (Kml); Mzamba, Mboyti & Mngazana (K1) KOEGEL FONTEIN (Kk) 22° 145 *-J c 22° C i I s KAROO DOLERITE KOMATIPOORT DRAKENSBERG (Jdr); LEBOMBO (Jl); (J-d); (Jk); O s OF Z a Tshokwane Granophyre SUURBERG (Js); BUMBENI (Jb) (Jts) r P-* O u Musina S J Z2 E 200 Molteno, Elliot, Clarens, Ntabeni, Nyoka *-J c M i Z2 Kml s Zme Z4 V4 Jl s C T I a *-J i R V4 O r O Tarkastad *t THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA O T Z P-* O F O Zme P-* 250 R Z2 U R A V4 A E !-d K P-* E n Adelaide Pa N a B i A !s Kml m H r !s P e AND ECCA Pe *-J P Z2 P-* *-J Jl C 300 *-J I DWYKA C-Pd s O P-* !-d u Z !s o !s r O !bl e R4 Zgh f E i THE KINGDOMS OF LESOTHO AND SWAZILAND n A Msikaba Dm WITTEBERG D-Cw o L Louis Trichardt V4 !4 b A r E P Zba a & ti P V4 C Zba V-sy Vsc A BOKKEVELD Db Jl - Z2 C n R4 !w a i Zba r Z1 Zgi M b NATAL On TABLE MOUNTAIN O-Dt Vkd m a !-d C CAPE GRANITE (N-"c); 2008 KLIPHEUWEL "k !4 Vr 545 NAMA (N-"n); KUBOOS-BREMEN (N-"k); P-* *-J Zgh &ti VANRHYNSDORP (N-"v); Yzerfontein Gabbro-monzonite ("y) Zgh Vle O CANGO CAVES, C-Pd Vro R4 KANSA (N-"ck) MALMESBURY (Nm); N KAAIMANS (Nk); GAMTOOS (Nga) Zp Zp Zgh A Ellisras I R4 B I !w Zg Z M GARIEP Ng 1:2 000 000 &6 A N Vle -

Weskus Regional Trends 2017

Weskus Regional Trends 2017 An inspiring place to know Contents 1. Methodology 2. Participation and sample size 3. Executive Summary 4. Weskus Visitor Trends & Patterns 4.1 Origin of visitors 4.2 Age profile of visitors 4.3 Travel group size 4.4 Mode of transport 4.5 Main purpose of visit 4.6 Top activities undertaken in the Weskus 4.7 Overnight vs. Day Visitors 4.8 Length of stay 4.9 Accommodation usage 4.10 Average spend in the Weskus 4.11 Top Information Sources 5. Weskus Towns 6. Trends and patterns by origin of visitors 7. Performance of the Weskus Attractions 8. Weskus New Routes 9. Weskus New Tourism Developments 10. Acknowledgements 1. Methodology This report provides an overview of the tourism trends and patterns in the Weskus. The findings will illustrate key visitor trends obtained from the regional visitor tracking survey. Responses to the regional visitor tracking surveys are used as a proxy to indicate the key trends within the Western Cape and the various regions. It is important to note that absolute figures cannot be determined from these surveys, as the survey responses are a sample of the tourists into the respective tourism offices across the Western Cape, and would thus represent a sample of the visitors. Therefore, where statistically relevant absolute numbers may be given, however, a share is provided to indicate the trend. This is based on international best practice in the use of surveys within the tourism industry for determining key trends. Definition: Tourist: refers to any visitor travelling to a place other than that of his/her own environment for more than one night, but less than 12 months and for whom the main purpose of the trip is other than the exercise of an activity remunerated for from within the place visited. -

The Distribution of the Economic Mineral Resource Potential in The

News & Views Distribution of economic mineral resource potential in the Western Cape Page 1 of 4 The distribution of the economic mineral resource AUTHORS: potential in the Western Cape Province Luncedo Ngcofe1 Doug I.Cole1 South Africa is blessed with vast mineral resources. The formal exploitation of mineral resources in South Africa started with copper mining in Namaqualand (near Springbok in the Northern Cape Province) in the mid-1800s. AFFILIATION: 1 The discovery of diamonds near Kimberley in 1867 and gold on the Witwatersrand in 1886 led to the significant Council for Geoscience, growth of the mining industry in South Africa. In 1995, it was reported that approximately 57 different minerals Cape Town, South Africa were sourced from 816 mines and quarries,1 with the most important mining provinces being the North West (as a large producer of platinum group metals and gold); Gauteng (gold); Mpumalanga (coal) and the Free State CORRESPONDENCE TO: (gold). Although the Western Cape is classified as being the least productive in terms of mineral resources,1 it Luncedo Ngcofe has a large potential for the exploitation of industrial minerals. These often neglected resources comprise a highly diverse group of vitally important minerals that are used in a variety of applications ranging from everyday products EMAIL: to highly sophisticated materials. Here we describe economic or potentially economic minerals occurring in the [email protected] Western Cape in terms of their geological setting. POSTAL ADDRESS: Geology Council for Geoscience, PO Box The occurrence of a mineral resource is always determined by the geological setting of a region.