The Distribution of the Economic Mineral Resource Potential in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LIBRARY ROUTE Indlela Yamathala Eencwadi Boland Control Area Geographic and Demographic Overview

THE LIBRARY ROUTE Indlela yamathala eencwadi Boland Control Area geographic and demographic overview Following up on our series, Insider’s View, in which six library depots and one Wheelie readers were introduced to the staff of the West- Wagon in the area. ern Cape Provincial Library Service and all its ac- By the end of December 2010 the tivities and functions, we are embarking on a new total book stock at libraries in the region series, The library route, in which the 336 libraries amounted to 322 430 items. that feed readers’ needs will be introduced. The area served is diverse and ranges We start the series off with the libraries in from well-known coastal towns to inland the Boland Control Area and as background we towns in the Western Cape. publish a breakdown of the libraries in the various Service points municipalities. Overstrand Municipality libraries Gansbaai STEVEN ANDRIES Hangklip Hawston Assistant Director Chief Library Assistant Moreen September who is Hermanus Steven’s right-hand woman Kleinmond Introduction Mount Pleasant Stanford The Western Cape Provincial Library Service: Zwelihle Regional Organisation is divided into three Theewaterskloof Municipality libraries control areas: Boland, Metropole and Outeni- Worcester and Vanrhynsdorp region from Vanrhynsdorp. Caledon qua. Each control area consists of fi ve regional Genadendal libraries and is headed by an assistant director The staff complement for each region in the Boland control area consists normally of Grabouw and supported by a chief library assistant. Greyton The fi ve regional offi ces in the Boland con- a regional librarian, two library assistants, a driver and a general assistant. -

Shore Angling Ladies (Langebaan)

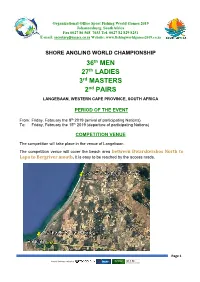

Organizational Office Sport Fishing World Games 2019 Johannesburg, SouthAfrica Fax 0027 86 568 7653 Tel. 0027 82 829 8251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fishingworldgames2019.co.za SHORE ANGLING WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP 36th MEN 27th LADIES 3rd MASTERS 2nd PAIRS LANGEBAAN, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA PERIOD OF THE EVENT From: Friday, February the 8th 2019 (arrival of participating Nations) To: Friday, February the 15th 2019 (departure of participating Nations) COMPETITION VENUE The competition will take place in the venue of Langebaan. The competition venue will cover the beach area between Dwarskersbos North to Lapa to Bergriver mouth. It is easy to be reached by the access roads. Page 1 Event Partners includes: Organizational Office Sport Fishing World Games 2019 Johannesburg, SouthAfrica Fax 0027 86 568 7653 Tel. 0027 82 829 8251 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.fishingworldgames2019.co.za Welcome by the President of the South African Shore Angling Association Dear angling friends, It is with great pleasure that we invite, on behalf of the South African Shore Angling Association, your national Federation to participate in the 2019 Shore Angling World Championships We are honored to partner with SASACC and that C.I.P.S. and FIPS-M have granted South Africa, and the village of Langebaan the opportunity and trust to host the world`s best sport sea anglers. We glad fully accept the challenge to present the most memorable tournament your Federation / Association will have ever experienced as our angling is the best in the world. South Africa is the Rainbow nation of the world due to our various cultures and we invite you to share our hospitality and natural beauty. -

Geoclip Volume 33

VOLUME 33 . JUNE 2013 INSIDE: The role of the Council for The role of the Geoscience and the Department of Mineral Resources in the organisation th Council for Geoscience of the 35 IGC I 1 Danie Barnardo Ranking of major water ingress areas and the Department of in the East Rand I 2 Marubini Selaelo Mineral Resources in the Shale gas cap rocks in the Karoo Basin I 3 th Dawn Black organisation of the 35 IGC Location of seismic events in the Central Rand GoldfieldI 5 Azangi Mangongolo Open-source geophysical 3D modelling and interpretation I 6 Patrick Cole Assessment of aquatic environments in the Witwatersrand goldfieldsI 7 Vongani Maboko German-South African workshop on data integration techniques applied to Earth science data I 8 Detlef Eberle Earthquake catalogue for southern Africa I 9 Thifhelimbilu Mulabisana Geochemical mapping in KwaZulu- Natal I 10 Sibongiseni Hlatshwayo/ Eliah Mulovhedzi Promoting geoheritage in the Cape Mxolisi Kota and Richard Viljoen, Co-Presidents of the Local Organising Committee. I 12 Doug Cole At the 33rd International Geological The South African Government clearly Celebrating International Museum Congress (IGC), which was held in demonstrated its support for this event Day I 13 Oslo, Norway in 2008, the Council for by discussing the 35th IGC at a Cabinet Kholisile Nzolo Geoscience led the bid to host the Meeting on 18 April 2012. Feedback th New fluxer for the Laboratory I 14 35 IGC in 2016, supported by the from the meeting indicated that the Corlien Cloete Geological Society of South Africa Cabinet endorsed the importance of and the South African Ambassador the 35th IGC and supports the event. -

GTAC/CBPEP/ EU Project on Employment-Intensive Rural Land Reform in South Africa: Policies, Programmes and Capacities

GTAC/CBPEP/ EU project on employment-intensive rural land reform in South Africa: policies, programmes and capacities Municipal case study Matzikama Local Municipality, Western Cape David Mayson, Rick de Satgé and Ivor Manuel with Bruno Losch Phuhlisani NPC March 2020 Abbreviations and acronyms BEE Black Economic Empowerment CASP Comprehensive Agricultural Support Programme CAWH Community Animal Health Worker CEO Chief Executive Officer CPA Communal Property of Association CPAC Commodity Project Allocation Committee DAAC District Agri-Park Advisory Committee DAPOTT District Agri Park Operational Task Team DoA Department of Agriculture DRDLR Department of Rural Development and Land Reform DWS Department of Water and Sanitation ECPA Ebenhaeser CPA FALA Financial Assistance Land FAO Food and Agriculture Organisation FPSU Farmer Production Support Unit FTE Full-Time Equivalent GGP Gross Geographic Product GDP Gross Domestic Product GVA Gross Value Added HDI Historically Disadvantaged Individual IDP Integrated Development Plan ILO International Labour Organisation LED Local economic development LORWUA Lower Olifants Water Users Association LSU Large stock units NDP National Development Plan PDOA Provincial Department of Agriculture PGWC Provincial Government of the Western Cape PLAS Proactive Land Acquisition Strategy SDF Spatial Development Framework SLAG Settlement and Land Acquisition Grant SSU Small stock unit SPP Surplus People Project TRANCRAA Transformation of Certain Rural Areas Act WUA Water Users Association ii Table of Contents -

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022

Swartland Municipality Integrated Development Plan for 2017-2022 THIRD AMENDMENT 28 MAY 2020 INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN FOR 2017-2022 Compiled in terms of the Local Government: Municipal Systems Act, 2000 (Act 32 of 2000) Amendments approved by the Municipal Council on 28 May 2020 The Integrated Development Plan is the Municipality’s principal five year strategic plan that deals with the most critical development needs of the municipal area (external focus) as well as the most critical governance needs of the organisation (internal focus). The Integrated Development Plan – is adopted by the council within one year after a municipal election and remains in force for the council’s elected term (a period of five years); is drafted and reviewed annually in consultation with the local community as well as interested organs of state and other role players; guides and informs all planning and development, and all decisions with regard to planning, management and development; forms the framework and basis for the municipality’s medium term expenditure framework, annual budgets and performance management system; and seeks to promote integration by balancing the economic, ecological and social pillars of sustainability without compromising the institutional capacity required in the implementation, and by coordinating actions across sectors and spheres of government. AREA PLANS FOR 2020/2021 The five area plans, i.e. Swartland North (Moorreesburg and Koringberg), Swartland East (Riebeek West and Riebeek Kasteel), Swartland West (Darling and Yzerfontein), Swartland South (Abbotsdale, Chatsworth, Riverlands and Kalbaskraal) and Swartland Central (Malmesbury) help to ensure that the IDP is more targeted and relevant to addressing the priorities of all groups, including the most vulnerable. -

Call to Join the Verlorenvlei Coalition

TUNGSTEN MINE THREATENS WAY OF LIFE OF THOUSANDS AND PLACES RAMSAR-SITE VERLORENVLEI AT HIGH RISK · We the people of the Verlorenvallei stand as one against a threat which could destroy our way of life and our valley. · We the farm workers, fishermen, farmers and entrepreneurs will not allow the pollution of our air, water or land or loss of our livelihoods for the sake of a greedy few. · We the lovers of nature reject further desecration of the already endangered Verlorenvlei and the unique and wide variety of animals, birds, reptiles and plants which have survived the depredations of humans. · We will protect the rare and largely unexplored rich pre-historical heritage for those who may follow us. · We have formed the Verlorenvlei Coalition; we are growing steadily, please join. The Verlorenvlei Coalition (VC) is a coalition of labour, business, civic organisations, environmental groups and local residents formed to preserve the integrity of the area and its people. We call our valley, which runs from Piketberg to Elands Bay, the Verlorenvallei. THE CHALLENGE: No less than 5 applicants have submitted applications to the DEPARTMENT OF MINING for the right to build an open-cast tungsten and molybdenum mine, one of these 50 hectares in extent and 200 metres deep, in the Moutonshoek Valley, between Piketberg and Elands Bay in the Western Cape. The Moutonshoek is a narrow valley, approximately 17 kilometres long and 3-4 kilometres wide, on the slopes of the Piketberg-mountain. THE VERLORENVLEI COALITION will oppose the proposed mining because: 1. It will destroy productive and profitable farms and detrimentally affect the food security of the Western Cape. -

Sampling and Estimation of Diamond Content in Kimberlite Based on Microdiamonds Johannes Ferreira

Sampling and estimation of diamond content in kimberlite based on microdiamonds Johannes Ferreira To cite this version: Johannes Ferreira. Sampling and estimation of diamond content in kimberlite based on micro- diamonds. Other. Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, 2013. English. NNT : 2013ENMP0078. pastel-00982337 HAL Id: pastel-00982337 https://pastel.archives-ouvertes.fr/pastel-00982337 Submitted on 23 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. N°: 2009 ENAM XXXX École doctorale n° 398: Géosciences et Ressources Naturelles Doctorat ParisTech T H È S E pour obtenir le grade de docteur délivré par l’École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris Spécialité “ Géostatistique ” présentée et soutenue publiquement par Johannes FERREIRA le 12 décembre 2013 Sampling and Estimation of Diamond Content in Kimberlite based on Microdiamonds Echantillonnage des gisements kimberlitiques à partir de microdiamants. Application à l’estimation des ressources récupérables Directeur de thèse : Christian LANTUÉJOUL Jury T M. Xavier EMERY, Professeur, Université du Chili, Santiago (Chili) Président Mme Christina DOHM, Professeur, Université du Witwatersrand, Johannesburg (Afrique du Sud) Rapporteur H M. Jean-Jacques ROYER, Ingénieur, HDR, E.N.S. Géologie de Nancy Rapporteur M. -

Predicting Wetland Occurrence in the Arid to Semi— Arid 1 Interior of the Western Cape, South Africa, for Improved 2 Mapping and Management

Predicting Wetland Occurrence in the Arid to Semi— Arid 1 Interior of the Western Cape, South Africa, for Improved 2 Mapping and Management Donovan Charles Kotze ( [email protected] ) University of KwaZulu-Natal https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9048-1773 Nick Rivers-Moore University of KwaZulu-Natal Michael Grenfell University of the Western Cape Nancy Job South African National Biodiversity Institute Research Article Keywords: drylands, hydrogeomorphic type, logistic regression, probability, vulnerability Posted Date: August 17th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-716396/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License 1 Predicting wetland occurrence in the arid to semi—arid 2 interior of the Western Cape, South Africa, for improved 3 mapping and management 4 5 D. C. Kotze1*, N.A. Rivers-Moore1,2, N. Job3 and M. Grenfell4 6 1Centre for Water Resources Research, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Private Bag X01, 7 Scottsville, 3209, South Africa 8 2Freshwater Research Centre, Cape Town, South Africa 9 3Kirstenbosch Research Centre, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Private Bag X7, 10 Newlands, Cape Town, 7945, South Africa 11 4Institute for Water Studies, Department of Earth Science, University of the Western Cape, 12 Private Bag X17, Bellville, 7535, South Africa 13 *Corresponding author: [email protected] 14 15 Abstract 16 As for drylands globally, there has been limited effort to map and characterize such wetlands in 17 the Western Cape interior of South Africa. Thus, the study assessed how wetland occurrence and 18 type in the arid to semi-arid interior of the Western Cape relate to key biophysical drivers, and, 19 through predictive modelling, to contribute towards improved accuracy of the wetland map layer. -

Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast

Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling Final May 2010 REPORT TITLE : Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling CLIENT : Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management PROJECT : Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast AUTHORS : D. Blake N. Chimboza REPORT STATUS : Final REPORT NUMBER : 769/2/1/2010 DATE : May 2010 APPROVED FOR : S. Imrie D. Blake Project Manager Task Leader This report is to be referred to in bibliographies as: Umvoto Africa. (2010). Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Assessment for a Select Disaster Prone Area Along the Western Cape Coast. Phase 2 Report: Eden District Municipality Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling. Prepared by Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd for the Provincial Government of the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning: Strategic Environmental Management (May 2010). Phase 2: Eden DM Sea Level Rise and Flood Risk Modelling 2010 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION Umvoto Africa (Pty) Ltd was appointed by the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning (DEA&DP): Strategic Environmental Management division to undertake a sea level rise and flood risk assessment for a select disaster prone area along the Western Cape coast, namely the portion of coastline covered by the Eden District (DM) Municipality, from Witsand to Nature’s Valley. -

The Sauropodomorph Biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of Southern Africa: Tracking the Evolution of Sauropodomorpha Across the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary

Editors' choice The sauropodomorph biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of southern Africa: Tracking the evolution of Sauropodomorpha across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary BLAIR W. MCPHEE, EMESE M. BORDY, LARA SCISCIO, and JONAH N. CHOINIERE McPhee, B.W., Bordy, E.M., Sciscio, L., and Choiniere, J.N. 2017. The sauropodomorph biostratigraphy of the Elliot Formation of southern Africa: Tracking the evolution of Sauropodomorpha across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 62 (3): 441–465. The latest Triassic is notable for coinciding with the dramatic decline of many previously dominant groups, followed by the rapid radiation of Dinosauria in the Early Jurassic. Among the most common terrestrial vertebrates from this time, sauropodomorph dinosaurs provide an important insight into the changing dynamics of the biota across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. The Elliot Formation of South Africa and Lesotho preserves the richest assemblage of sauropodomorphs known from this age, and is a key index assemblage for biostratigraphic correlations with other simi- larly-aged global terrestrial deposits. Past assessments of Elliot Formation biostratigraphy were hampered by an overly simplistic biozonation scheme which divided it into a lower “Euskelosaurus” Range Zone and an upper Massospondylus Range Zone. Here we revise the zonation of the Elliot Formation by: (i) synthesizing the last three decades’ worth of fossil discoveries, taxonomic revision, and lithostratigraphic investigation; and (ii) systematically reappraising the strati- graphic provenance of important fossil locations. We then use our revised stratigraphic information in conjunction with phylogenetic character data to assess morphological disparity between Late Triassic and Early Jurassic sauropodomorph taxa. Our results demonstrate that the Early Jurassic upper Elliot Formation is considerably more taxonomically and morphologically diverse than previously thought. -

1 1 the Physical Characteristics of a CO2 Seeping Fault

1 The Physical Characteristics of a CO2 Seeping Fault: the implications of fracture 2 permeability for carbon capture and storage integrity 3 4 Clare E. Bond1* 5 Yannick Kremer2 6 Gareth Johnson3 7 Nigel Hicks4 8 Robert Lister5 9 Dave G. Jones5 10 Stuart Haszeldine3 11 Ian Saunders6 12 Stuart Gilfillan3 13 Zoe K. Shipton2 14 Jonathan Pearce5 15 16 1Department of Geology and Petroleum Geology, University of Aberdeen, Meston Building, 17 Kings College, Aberdeen, AB24 3UE, UK ([email protected]) 18 2Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Strathclyde, James Weir 19 Building, Glasgow, G1 1XJ ([email protected]; [email protected]) 20 3School of Geosciences, University of Edinburgh, Grant Institute, Kings Buildings, James 21 Hutton Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3FE ([email protected]; [email protected]; 22 [email protected]) 23 4 Council for Geoscience, 139 Jabu Ndlovu Street, Pietermaritzburg, KwaZulu-Natal, South 24 Africa 3200 ([email protected]) 25 5 British Geological Survey, Environmental Science Centre, Nicker Hill, Keyworth, Nottingham 26 NG12 5GG ([email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]) 27 6 Council for Geoscience, 280 Pretoria St, Silverton, Pretoria, 0184 ([email protected]) 28 *Corresponding Author [email protected] 29 30 31 32 Highlights 33 34 CO2 migration is spatially associated with the Bongwana fault fracture corridor. 35 Cap rock permeability suggests that without fractures it would act as a flow barrier. 36 Elevated CO2 concentration and flux are measured across the fracture corridor. 37 Fracture intensity and orientation variability creates permeability heterogeneity. -

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex

Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex By Karen E. Poole B.A. in Geology, May 2004, University of Pennsylvania M.A. in Earth and Planetary Sciences, August 2008, Washington University in St. Louis A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 31, 2015 Dissertation Directed by Catherine Forster Professor of Biology The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University certifies that Karen Poole has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 10th, 2015. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. Phylogeny and Biogeography of Iguanodontian Dinosaurs, with Implications from Ontogeny and an Examination of the Function of the Fused Carpal-Digit I Complex Karen E. Poole Dissertation Research Committee: Catherine A. Forster, Professor of Biology, Dissertation Director James M. Clark, Ronald Weintraub Professor of Biology, Committee Member R. Alexander Pyron, Robert F. Griggs Assistant Professor of Biology, Committee Member ii © Copyright 2015 by Karen Poole All rights reserved iii Dedication To Joseph Theis, for his unending support, and for always reminding me what matters most in life. To my parents, who have always encouraged me to pursue my dreams, even those they didn’t understand. iv Acknowledgements First, a heartfelt thank you is due to my advisor, Cathy Forster, for giving me free reign in this dissertation, but always providing valuable commentary on any piece of writing I sent her, no matter how messy.