China and Eurasia Forum Quarterly Vol 6, No 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public M&A 2013/14: the Leading Edge

Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge June 2014 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Contents 2 Introduction 31 Italy 31 Deal activity 4 Global market trend map 31 Market trends 6 The leading edge: country perspectives 32 Case studies 6 Austria 34 Japan 6 Deal activity 34 Deal activity 6 Market trends 34 Market trends 6 Changes to the legislative framework 35 Case study 7 Case study 36 Netherlands 8 Belgium 36 Deal activity 8 Market trends 36 Market trends 8 Changes to the legislative framework 37 Changes to the legislative framework 9 Case study 38 Points to watch 39 Case studies 10 China 10 Deal activity 40 Spain 11 Market trends 40 Deal activity 11 Case study 40 Market trends 41 Changes to the legislative framework 12 EU 42 Points to watch 12 Changes to the legislative framework 43 Case studies 14 France 44 UK 14 Market trends 44 Deal activity 15 Changes to the legislative framework 45 Market trends 16 Case studies 45 Changes to the legislative framework 19 Germany 46 Deal protection measures 19 Deal activity 47 Points to watch 20 Market trends 48 Case study 22 Case study 50 US 24 Hong Kong and Singapore 50 Deal activity 24 Deal activity 50 Market trends and judicial and 25 Market trends legislative developments 28 Market trends 51 Litigation as a cost of doing business 29 Case study 53 Case study 54 Contacts Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP 1 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Introduction Market trends 2013 saw a modest increase in global public M&A activity. -

24 June 2013 Not for Release, Publication Or Distribution, in Whole

24 June 2013 Not for release, publication or distribution, in whole or in part, in or into any jurisdiction where to do so would constitute a violation of the relevant laws of such jurisdiction Update from the Independent Committee of the Board of Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation PLC (the "Company" or "ENRC") Independent Committee's response to the Offer for ENRC The Independent Committee of the Board of ENRC (the "Independent Committee") notes the Rule 2.7 announcement (the "Announcement") earlier today by Eurasian Resources Group B.V. (the "Eurasian Resources Group" or the “Offeror”), a newly incorporated company formed by a consortium comprising Alexander Machkevitch, Alijan Ibragimov, Patokh Chodiev and the State Property and Privatisation Committee of the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Kazakhstan (together, the "Consortium"), of the terms of an offer to be made by Eurasian Resources Group to acquire all of the issued and to be issued share capital of ENRC (other than the ENRC Shares already held by the Offeror). The defined terms in this announcement shall have the meaning given to them in the Announcement unless indicated otherwise herein. Under the terms of the Offer, Relevant ENRC Shareholders would receive US$2.65 in cash and 0.230 Kazakhmys Consideration Shares for each ENRC Share. The Offer values ENRC at 234.3 pence per ENRC Share (having an aggregate value of approximately £3.0 billion) based on the mid-market closing share price of Kazakhmys on Friday 21 June 2013. This represents a price which is lower than the proposal put to the Independent Committee by the Consortium on 16 May 2013 of 260 pence per ENRC Share and constitutes: • a discount of 27 per cent. -

Onderzoeksopzet

'Truth is the first casualty' How does embedded journalism influence the news coverage of TFU in the period 2006-2010? Barbara Werdmuller Master thesis Political Science Campus Den Haag, University of Leiden June 2012 For all soldiers and journalists who risk their lives by fulfilling their private mission in war zones. 2 Word of thanks The author of this research wishes to thank the following persons for their contribution to the realization of this thesis. First, the editors and journalists of the analyzed papers and news magazines for their feedback regarding reporter status and views regarding (non-)embedded journalism. Second, the two supervisors Jan van der Meulen and Frits Meijerink for their constructive feedback and advice with regard to analysis of literature, execution of the research and statistical analysis. Third, Maria Werdmuller for assistance with the import of analyzed data in SPSS. Last but not least, Carlos Vrins and Mark Pijnenburg for their feedback and words of encouragement in the process of research and writing of the thesis. 3 Table of content Summary 6 1 Introduction: 'Truth is the first casualty' 7 1a The phenomenon of embedded journalism 7 1b Research question and structure of the research report 8 2 War journalism and embedded journalism 10 2a The impact of war journalism 10 2b The profession of war journalist 11 2c Developments in war journalism in the 20th and 21th century 13 2d A case of embedded journalism: Iraq 13 2e Overview 15 3 A Dutch case of embedded journalism: Task Force Uruzgan 16 3a The embed -

Soldiers in Conflict

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/208863 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-10-04 and may be subject to change. Soldiers in Conflict Moral Injury, Political Practices and Public Perceptions Typography and design: Merel de Hart, Multimedia NLDA, Breda Cover illustration: Mei-Li Nieuwland Illustration (Lonomo), Amsterdam © 2019 Tine Molendijk All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the author. ISBN/EAN: 978-94-93124-04-2 Soldiers in Conflict Moral Injury, Political Practices and Public Perceptions Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen op gezag van de rector magnificus prof. dr. J.H.J.M. van Krieken, volgens besluit van het college van decanen in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 7 januari 2020 om 10:30 uur precies door Tine Molendijk geboren op 23 februari 1987 te Ezinge Promotoren Prof. dr. D.E.M. Verweij Prof. dr. F.J. Kramer Nederlandse Defensie Academie Copromotor Dr. W.M. Verkoren Manuscriptcommissie Prof. dr. M.L.J. Wissenburg Prof. dr. J.J.L. Derksen Prof. dr. J. Duyndam Universiteit voor Humanistiek Dr. E. Grassiani Universiteit van Amsterdam Dr. C.P.M. Klep Universiteit Utrecht Onderzoek voor dit proefschrift werd mede mogelijk gemaakt door de Nederlandse Defensie Academie (NLDA) Contents Contents Contents ..................................................................................................................6 Glossary of Military Terms and Ranks ..................................................................... -

Isaacs 2009 Between

RADAR Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. No quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. You must obtain permission for any other use of this thesis. Copies of this thesis may not be sold or offered to anyone in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright owner(s). When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Isaacs, R. (2009). Between informal and formal politics : neopatrimonialism and party development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. PhD thesis. Oxford Brookes University. go/radar www.brookes.ac.uk/ Directorate of Learning Resources Between Informal and Formal Politics: Neopatrimonialism and Party Development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan Rico Isaacs Oxford Brookes University A Ph.D. thesis submitted to the School of Social Sciences and Law Oxford Brookes University, in partial fulfilment of the award of Doctor of Philosophy March 2009 98,218 Words Abstract This study is concerned with exploring the relationship between informal forms of political behaviour and relations and the development of formal institutions in post- Soviet Central Asian states as a way to explain the development of authoritarianism in the region. It moves the debate on from current scholarship which places primacy on either formal or informal politics in explaining modern political development in Central Asia, by examining the relationship between the two. -

Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges

Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges Mert Kayhan & Merijn Hartog, editors 2013 GREENWOOD PAPER 28 Promoting Good Governance in the Security Sector: Principles and Challenges Editors: Mert Kayhan and Merijn Hartog First published in February 2013 by The Centre of European Security Studies (CESS) Lutkenieuwstraat 31 A 9712 AW Groningen The Netherlands Chairman of the Board: Peter Volten ISBN: 978-90-76301-29-7 Copyright © 2013 by CESS All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Centre for European Security Studies (CESS) is an independent institute for research, consultancy, education and training, based in the Netherlands. Its aim is to promote transparent, accountable and effective governance of the security sector, broadly defined. It seeks to advance democracy and the rule of law, help governments and civil society face their security challenges, and further the civilized and lawful resolution of conflict. The Man behind the Greenwood Papers Resting his fists on the lectern, he would fix his audience with a glare and pronounce: “REVEAL, EXPLAIN AND JUSTIFY.” It was his golden rule of democratic governance. David Greenwood was born in England in 1937 and died in 2009 in Scotland. He first worked for the British Ministry of Defence, then went on to teach political economy at Aberdeen University, where he later became the director of the Centre for Defence Studies. In 1997, David Greenwood joined the Centre for European Security Studies in the Netherlands as its Research Director. -

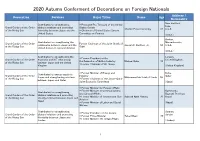

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals Address / Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age Nationality New Hartford, Contributed to strengthening * President Pro Tempore of the United Iowa, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting States Senate Charles Ernest Grassley 87 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun friendship between Japan and the * Chairman of United States Senate United States Committee on Finance (U.S.A.) Boston, Contributed to strengthening the Massachusetts, Grand Cordon of the Order Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of relationship between Japan and the Joseph F. Dunford Jr. 64 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun Staff United States on national defense (U.S.A.) Contributed to strengthening the London, * Former President of the Grand Cordon of the Order economic and ICT relationship United Kingdom Confederation of British Industry Michael Rake 72 of the Rising Sun between Japan and the United * Former Chairman of BT Group Kingdom (United Kingdom) * Former Minister of Energy and Doha, Contributed to energy supply to Grand Cordon of the Order Industry Qatar Japan and strengthening relations Mohammed bin Saleh Al Sada 59 of the Rising Sun * Former Chairman of the Japan-Qatar between Japan and Qatar Joint Economic Committee (Qatar) * Former Minister for Foreign Affairs * Former Minister of Communications Kathmandu, Contributed to strengthening and General Affairs Bagmati Province, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting * Former Minister of Tourism and Civil Ramesh Nath Pandey 76 Nepal of -

Order and Chaos in the Interoperability Continuum Gans, Ben

Tilburg University Stabilisation operations as complex systems - order and chaos in the interoperability continuum Gans, Ben DOI: 10.26116/center-lis-1916 Publication date: 2019 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Gans, B. (2019). Stabilisation operations as complex systems - order and chaos in the interoperability continuum. CentER, Center for Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.26116/center-lis-1916 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 29. sep. 2021 Stabilisation operations as complex systems order and chaos in the interoperability continuum 1 2 Stabilisation operations as complex systems order and chaos in the interoperability continuum PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan Tilburg University op gezag van prof. dr. G.M. Duijsters, als tijdelijk waarnemer van de functie rector magnificus en uit dien hoofde vervangend voorzitter van het college voor promoties, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties aangewezen commissie in de Aula van de Universiteit op maandag 01 juli 2019, om 13.30 uur door Ben Gans geboren op 09 oktober 1981 te Utrecht 3 Promotor: Prof. -

The Use of Caveats in Coalition Warfare Derek Scott

(Somewhat) Willing & Able: the Use of Caveats in Coalition Warfare Derek Scott Ray Bachelor of the Arts, Baylor University, 2010 Masters of the Arts, American Military University, 2012 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Politics University of Virginia August 2020 Committee: Phillip B.K. Potter (Chair) Dale Copeland Col Patrick H. Donley John M. Owen IV i The views expressed in this dissertation are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. ii Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 The Argument ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Brief Plan of the Dissertation ............................................................................................................... 10 Explaining Caveats in Post-Cold War Military Coalitions ......................................................... 13 National Preferences Regarding the Use of Military Force .............................................................. 14 Caveats as the Result of Preference Divergence ................................................................................ 31 Case Selection ....................................................................................................................................... -

SP's Landforces 02-09.Indd

I s s u e 2 • 2 0 0 9 V o l 6 N o 2 SP’s AN SP GUIDE PUBLICATION Sponsor of International Seminar - BMS - organised by Indian Army and CII LandWWW.SPSLANDFORCES.NET ForcesROUNDUP In This Issue T h e ONLY journal in Asia dedicated to Land Forces Smerch BM-30 can be M-109 has been A Battle Management used as an independent continually upgraded and System would provide artillery system, improved to today’s current situational awareness with shoot-and-scoot version, the M-109A6 to a unit/subunit/ capabilities, in the high- “Paladin”, which is used in detachment commander altitude mountainous US Army in its armoured and networking him areas of Jammu and and mechanised divisions. down to an individual Kashmir soldier or a tank BRIGADIER (RETD) LT GENERAL (RETD) LT. GENERAL (RETD) 6 VINOD ANAND? 7 R.S. NAGRA? 10 V.K. KAPOOR? EditorialEditorial Face to Face The situation in Pakistan is deteriorating rapidly. While on one hand we have seen the assertion of the popular will in the reinstatement of Justice Iftikhar Chaudhary, on the other hand the inter- nal security situation in Pakistan is in shambles. The suicide bombing of a mosque in Jamrud in Khyber agency on March 27, 2009, was followed by an audacious assault on the Police Training Centre at Manawan on March 30 on the outskirts of Lahore. Sunday April 05, saw yet another suicide blast this time by a teenager, in a Shia mosque in Chakwal in Punjab which was executed a few hours after the targeting of the security forces near the UN office, in the heart of Islamabad. -

The Curious World of Donald Trump's Private Russian Connections

Russia & The West The Curious World of Donald Trump’s Private Russian Connections James S. Henry Did the American people really know they were putting such a “well-connected” guy in the White House? Throughout Donald Trump’s presidential campaign he expressed glowing admiration for Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Many of Trump’s adoring comments were utterly gratuitous. After his Electoral College victory, Trump continued praising the former head of the KGB while dismissing the findings of all 17 American national security agencies that Putin directed Russian government interference to help Trump in the 2016 American presidential election. As veteran investigative economist and journalist Jim Henry shows below, a robust public record helps explain the fealty of Trump and his family to this murderous autocrat and the network of Russian oligarchs. Putin and his billionaire friends have plundered the wealth of their own people. They have also run numerous schemes to defraud governments and investors in the United States and Europe. From public records, using his renowned analytical skills, Henry shows what the mainstream news media in the United States have failed to report in any meaningful way: For three decades Donald Trump has profited from his connections to the Russian oligarchs, whose own fortunes depend on their continued fealty to Putin.We don’t know the full relationship between Donald Trump, the Trump family and their enterprises with the network of world-class criminals known as the Russian oligarchs. Henry acknowledges that his article poses more questions than answers, establishes more connections than full explanations. But what Henry does show should prompt every American to rise up in defense of their country to demand a thorough, out-in-the-open congressional investigation with no holds barred. -

Universitymgimo

Education For a Global FuturE UNIVERSITYMGIMO moscow statE institutE oF intErnational rElations intErnational rElations arEa studiEs Economics lEGal STUDIEs Political sciEncE manaGEmEnt Journalism Public rElations EnvironmEntal manaGEmEnt tradE, markEtinG and rEtail businEss statE and Public administration UNIVERSITYMGIMO FROM GLORY TO SUCCESS Nowadays MGIMO is a dynamic university, characterized by a strong international identity, spirit of innovation and global goals. Over its 70-year history, it went from a ‘‘diplomatic school‘‘ to a worldwide recognized university that is able to meet the most ambitious educational and research challenges. Its renomme is supported by Nhigh positions in university and think tanks rankings. Even the Guinness Book of World Records acknowledged MGIMO for the most languages taught – 53 actual languages. Every academic year sees more than 6,000 students with nearly 1,000 of them coming from abroad to study in MGIMO. The range of academic disciplines is constantly expanding as new departments and programs are launched each year. With the experience we have gained, we are always developing – successfully enhancing our cooperation with leading universities around the world. Our alumni community comprises more than 45,000 graduates with brilliant careers in both public and private sectors. anatoly torkunov Rector of MGIMO University Full Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences MGIMO Graduate 1972 MGIMO UNIVERSITY WHY MGIMO? TEN REASONS FOR MGIMO russia’s PrEmiEr univErsitY trulY intERNATIONAL GLOBAL rECOGnition widE COURSE sElEction OUTSTANDING ACADEmic ACCEss WORLD rENOWNEd rEsEarcH INNOVATIVE EDUCATION ACADEmic EXcEllEncE WORLDWIDE nETWORKING GrEAT social liFE MGIMO is Russia’s most prestigious educa- double-degree programs, offered in partner- tional institution for young people with inter- ship with a wide range of universities from national interests.