Ungp on Business and Human Rights in Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public M&A 2013/14: the Leading Edge

Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge June 2014 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Contents 2 Introduction 31 Italy 31 Deal activity 4 Global market trend map 31 Market trends 6 The leading edge: country perspectives 32 Case studies 6 Austria 34 Japan 6 Deal activity 34 Deal activity 6 Market trends 34 Market trends 6 Changes to the legislative framework 35 Case study 7 Case study 36 Netherlands 8 Belgium 36 Deal activity 8 Market trends 36 Market trends 8 Changes to the legislative framework 37 Changes to the legislative framework 9 Case study 38 Points to watch 39 Case studies 10 China 10 Deal activity 40 Spain 11 Market trends 40 Deal activity 11 Case study 40 Market trends 41 Changes to the legislative framework 12 EU 42 Points to watch 12 Changes to the legislative framework 43 Case studies 14 France 44 UK 14 Market trends 44 Deal activity 15 Changes to the legislative framework 45 Market trends 16 Case studies 45 Changes to the legislative framework 19 Germany 46 Deal protection measures 19 Deal activity 47 Points to watch 20 Market trends 48 Case study 22 Case study 50 US 24 Hong Kong and Singapore 50 Deal activity 24 Deal activity 50 Market trends and judicial and 25 Market trends legislative developments 28 Market trends 51 Litigation as a cost of doing business 29 Case study 53 Case study 54 Contacts Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer LLP 1 Public M&A 2013/14: the leading edge Introduction Market trends 2013 saw a modest increase in global public M&A activity. -

24 June 2013 Not for Release, Publication Or Distribution, in Whole

24 June 2013 Not for release, publication or distribution, in whole or in part, in or into any jurisdiction where to do so would constitute a violation of the relevant laws of such jurisdiction Update from the Independent Committee of the Board of Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation PLC (the "Company" or "ENRC") Independent Committee's response to the Offer for ENRC The Independent Committee of the Board of ENRC (the "Independent Committee") notes the Rule 2.7 announcement (the "Announcement") earlier today by Eurasian Resources Group B.V. (the "Eurasian Resources Group" or the “Offeror”), a newly incorporated company formed by a consortium comprising Alexander Machkevitch, Alijan Ibragimov, Patokh Chodiev and the State Property and Privatisation Committee of the Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Kazakhstan (together, the "Consortium"), of the terms of an offer to be made by Eurasian Resources Group to acquire all of the issued and to be issued share capital of ENRC (other than the ENRC Shares already held by the Offeror). The defined terms in this announcement shall have the meaning given to them in the Announcement unless indicated otherwise herein. Under the terms of the Offer, Relevant ENRC Shareholders would receive US$2.65 in cash and 0.230 Kazakhmys Consideration Shares for each ENRC Share. The Offer values ENRC at 234.3 pence per ENRC Share (having an aggregate value of approximately £3.0 billion) based on the mid-market closing share price of Kazakhmys on Friday 21 June 2013. This represents a price which is lower than the proposal put to the Independent Committee by the Consortium on 16 May 2013 of 260 pence per ENRC Share and constitutes: • a discount of 27 per cent. -

Rule of Law Belgium 2017

Belgium 2017 Total: 77.94 Rule of Law Independence of the Judiciary : 7.83 Independence of judiciary from the executive is a principle developed in Belgium since its state independence in 1830. It was later enshrined by the Constitution. It is highly respected. Since federalization, Constitutional Court has become vital in peaceful resolution of conflicts of interest between the constituent regions or communities and in preventing discrimination. Another judicial body, Council of State, is the highest administrative court in the country, playing an important role in the peaceful settlement of inter-regional or inter-communal disputes. It also deals with legislation affecting human rights, freedom of commerce or other interaction between state bodies and private actors. Interviews with citizens fail to detect anybody who had paid a bribe to a judge, even though 25% think that there exists corruption in the courts. There certainly are sporadic outside influences by public opinion and/or political interference. According to GAN portal, efficiency or even efficacy of courts is but problematic. Judiciary is experiencing shortage of judges, hence backlog and even expiry of some important cases (such as those regarding transnational corruption). Corruption : 7.7 For several years now Belgium has been stagnating in its battle to eliminate corruption. The situation is very good, yet the final steps to make it excellent (such as in comparable Netherlands or Luxembourg) are missing. In the Transparency International`s Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, Belgium was ranked 15 (of 176). Social market economy, long experience in building anti- corruption mechanisms, trained professional administration and a highly developed citizens` awareness have narrowed the ground for - and led to relative rareness of - corruption. -

P U B L I C a T I E S

P U B L I C A T I E S 1 JANUARI – 31 DECEMBER 2001 2 3 INHOUDSOPGAVE Centrale diensten..............................................................................................................5 Coördinatoren...................................................................................................................8 Faculteit Letteren en Wijsbegeerte..................................................................................9 - Emeriti.........................................................................................................................9 - Vakgroepen...............................................................................................................10 Faculteit Rechtsgeleerdheid...........................................................................................87 - Vakgroepen...............................................................................................................87 Faculteit Wetenschappen.............................................................................................151 - Vakgroepen.............................................................................................................151 Faculteit Geneeskunde en Gezondheidswetenschappen............................................268 - Vakgroepen.............................................................................................................268 Faculteit Toegepaste Wetenschappen.........................................................................398 - Vakgroepen.............................................................................................................398 -

Annual Report 2012 CENTRE for LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT (CLAAS)

1 Annual Report CLAAS 2012 Edited & Complied by: Ms. Katherine Sapna (Deputy National Director/Program Officer) Ms. Rama Rasheed (Assistant Program Officer) Printed by: HOPE TIME PRINTERS 2 CENTRE FOR LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT Annual Report 2012 CENTRE FOR LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT (CLAAS) CLAAS-PAKISTAN 31-Katcha Ferozepur Road, Mozang Chungi Lahore, Pakistan Phone: 0092-42-37581720 Fax: 0092-42-37591571 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.claasfamily.com CLAAS-UK P.O Box 81, Southall Middlesex UB2 5 YQ United Kingdom Tel: 0044-0845 3670567 0044-0208 8611253 E-mail: [email protected] Web-Site: www.claas.org.uk 3 CENTRE FOR LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT CLAAS BOARD in 2012 CLAAS has a Board consisting of 09 members from different walks of life but share similar concerns of the promotion of human rights. CLAAS Board Chairman National Director +Most Rev. Dr. Andrew M. A. Joseph Francis MBE Francis Bishop of Multan Vice Chairman Rt. Rev. Samuel Robert Azraiah Treasurer Younis Rahi Rev. Fr. Inayat Bernard Mr. Amjad Saleem Minhas Mrs. Resha Qadir Mrs. Lesley Azad Mrs. Javaid William Bakhsh Marshall 4 CENTRE FOR LEGAL AID ASSISTANCE & SETTLEMENT List of CLAAS Staff Members in the year 2012 1. Mr. M.A Joseph Francis MBE, National Director 2. Ms. Katherine Sapna, Deputy National Director/Program Officer 3. Mr. Sohail Habel, Finance Manager 4. Ms. Neelam Uzma, Assistant Finance Manager 5. Mr. Joel Samuel, Internal Auditor 6. Mr. Nadeem Anthony Advocate, Research officer (Left in December 2012) 7. Ms. Rama Rasheed, Assistant Program Officer 8. Ms. Huma Lucas, Office Assistant 9. -

Isaacs 2009 Between

RADAR Oxford Brookes University – Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository (RADAR) Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. No quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. You must obtain permission for any other use of this thesis. Copies of this thesis may not be sold or offered to anyone in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright owner(s). When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Isaacs, R. (2009). Between informal and formal politics : neopatrimonialism and party development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. PhD thesis. Oxford Brookes University. go/radar www.brookes.ac.uk/ Directorate of Learning Resources Between Informal and Formal Politics: Neopatrimonialism and Party Development in post-Soviet Kazakhstan Rico Isaacs Oxford Brookes University A Ph.D. thesis submitted to the School of Social Sciences and Law Oxford Brookes University, in partial fulfilment of the award of Doctor of Philosophy March 2009 98,218 Words Abstract This study is concerned with exploring the relationship between informal forms of political behaviour and relations and the development of formal institutions in post- Soviet Central Asian states as a way to explain the development of authoritarianism in the region. It moves the debate on from current scholarship which places primacy on either formal or informal politics in explaining modern political development in Central Asia, by examining the relationship between the two. -

Children's Rights Convention Alternative Report by The

CHILDREN'S RIGHTS CONVENTION ALTERNATIVE REPORT BY THE BELGIAN NGOS September 2001 Kinderrechtencoalitie Vlaanderen vzw Coordination des ONG pour les droits de (Flemish Children’s Rights Coalition) l'enfant (CODE) Limburgstraat 62 (Coordinators of the NGOs for Children’s 9000 Gent Rights) Tel.: (00-32) 9/329.47.84 Rue Marché aux Poulets 30 E-mail : [email protected] 1000 Bruxelles Tel. : (00-32) 2/209.61.68 1 Fax. : (00-32) 2/209.61.60 E-mail : [email protected] 2 Presentation of the NGOs The “Coordination des ONG pour les droits de l’enfant” and the “Kinderrechtencoalitie Vlaanderen” have collaborated closely to produce this alternative to the official Belgian report. 1. La Coordination des ONG pour les droits de l’enfant The “Coordination des ONG pour les droits de l’enfant” (CODE) was founded in 1994 within the framework of the first official Belgian report was an initiative by the Belgian section of the Defence for International Children (DEI). Members today include: Amnesty International, ATD Quart Monde, the Belgian Committee for UNICEF, DEI International, Justice et Paix, la Ligue des droits de l’homme, la Ligue des familles and OMEP. These different associations have a common objective of developing specific actions to promote and defend children's rights in Belgium and in the world. Together, they have the following goals: · To monitor that the Convention concerning Children’s Rights is put in action by Belgium. · To develop a programme for informing, consciousness raising and educating about children’s rights. The “Coordination’s” programme aims to be vigilant and constructive. -

Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights in the Courts: Guidance for Judges, Prosecutors and | 3 Lawyers on ����������� of EU Directive 2017/541 on Combatting Terrorism

Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights in the Courts Guidance for Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers on of EU Directive 2017/541 on Combatting Terrorism Counter-Terrorism and Human Rights in the Courts: Guidance for Judges, Prosecutors and Lawyers on Application of EU Directive 2017/541 on Combatting Terrorism International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) Human Rights in Practice (HRiP) Nederlands Juristen Comité voor de Mensenrechten (NJCM) Scuola Superiore Sant’Anna di Pisa This Guidance was written by Helen Duffy (HRiP), Róisín Pillay and Karolína Babická (ICJ). November 2020 Counter-terrorism and human rights in the courts: guidance for judges, prosecutors and | 3 lawyers on of EU Directive 2017/541 on combatting terrorism Table of Contents I. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 5 II. Applicable international law standards in law and practice ..................................... 7 1. Respect and protection of the human rights of all affected by the criminal process .................................................................................................... 7 2. Investigating and appropriately charging serious violations and crimes under international law ................................................................................ 8 a) States must carry out prompt, thorough, independent investigations of serious acts of violence, by non-State and State actors, and hold to account those responsible ........................................................................................... -

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights at 10 the Impact of the Ungps on Courts and Judicial Mechanisms

UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights at 10 The Impact of the UNGPs on Courts and Judicial Mechanisms Disclaimer This report has been prepared in conjunction with the ‘UNGPs 10+’ project organized by the United Nations Working Group on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises to mark ten years since the adoption of the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs) by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. This report is designed to provide an overview of the application of the UNGPs by judicial and quasi- judicial mechanisms, and is prepared on the basis of material available generally up to January 2021. It is not intended nor is it to be used as a substitute for legal advice. The information provided to you in this report is not intended to create and does not create an attorney-client relationship with Debevoise or with any lawyer at Debevoise. You may inquire about legal representation by contacting the appropriate person at Debevoise. © Debevoise & Plimpton LLP All rights reserved. 2 Project Lead Authors David W. Rivkin Samantha J. Rowe Deborah Enix-Ross Partner, New York and London Partner, London and Paris Senior Advisor, New York [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Emily Austin Sophia Burton Aymeric Dumoulin Associate, Hong Kong Associate, London Associate, New York [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Nelson Goh Rhianna Hoover Jesse Hope Associate, London Associate, New York Trainee Associate, London [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Merryl Lawry-White Nadya Rouben Katherine Seifert Associate, London Associate, London Associate, Washington D.C. -

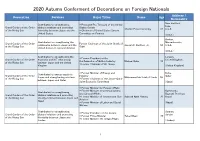

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals

2020 Autumn Conferment of Decorations on Foreign Nationals Address / Decoration Services Major Titles Name Age Nationality New Hartford, Contributed to strengthening * President Pro Tempore of the United Iowa, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting States Senate Charles Ernest Grassley 87 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun friendship between Japan and the * Chairman of United States Senate United States Committee on Finance (U.S.A.) Boston, Contributed to strengthening the Massachusetts, Grand Cordon of the Order Former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of relationship between Japan and the Joseph F. Dunford Jr. 64 U.S.A. of the Rising Sun Staff United States on national defense (U.S.A.) Contributed to strengthening the London, * Former President of the Grand Cordon of the Order economic and ICT relationship United Kingdom Confederation of British Industry Michael Rake 72 of the Rising Sun between Japan and the United * Former Chairman of BT Group Kingdom (United Kingdom) * Former Minister of Energy and Doha, Contributed to energy supply to Grand Cordon of the Order Industry Qatar Japan and strengthening relations Mohammed bin Saleh Al Sada 59 of the Rising Sun * Former Chairman of the Japan-Qatar between Japan and Qatar Joint Economic Committee (Qatar) * Former Minister for Foreign Affairs * Former Minister of Communications Kathmandu, Contributed to strengthening and General Affairs Bagmati Province, Grand Cordon of the Order bilateral relations and promoting * Former Minister of Tourism and Civil Ramesh Nath Pandey 76 Nepal of -

They Entered Without Any Rumour. Human Rights in the Belgian Legal

Goettingen Journal of International Law 4 (2012) 1, 291-311 They Entered without any Rumour. Human Rights in the Belgian Legal Periodicals Sebastiaan Vandenbogaerde Table of Contents A. Introduction ........................................................................................ 292 B. The Rechtskundig Weekblad ............................................................. 295 I. Belgian linguistic history ............................................................... 297 II. Quantitative analysis ...................................................................... 300 1. Autonomous doctrinal contributions .......................................... 300 2. Case law ..................................................................................... 301 C. External: Belgian cases procedural changes ...................................... 302 I. Linguistic issues create a greater attention for Strasbourg ............. 302 II. How a baby changed the focus in the legal periodicals ................. 306 III. The adoption of the 11th and 14th Protocol ............................... 308 IV. A Change of mentality in the Belgian legal world ..................... 310 D. Internal changes: the Editorial Board ................................................. 310 E. Conclusion ......................................................................................... 311 Sebastiaan Vandenbogaerde has a degree in history (2006) and law (2010). Since August 2010 he is researcher in the Department of Legal Theory and History at Ghent University. -

Trafficking in Human Beings in Belgium 2007-2008

Trafficking in Human Beings in Belgium 2007-2008 Human Rights Without Frontiers International 28 April 2009 Trafficking in Human Beings Index Trafficking in Human Beings .......................................................................................................................1 1.1. The Law of 10 August 2005................................................................................................................2 1.2. The law of 15 September 2006...........................................................................................................3 1.3. Criminal Legislation ..........................................................................................................................4 2. Trafficking in human beings: the implementation of the legal framework...............................................5 2.1. National Action Plan..........................................................................................................................5 2.2. Sectors................................................................................................................................................5 a. Prostitution....................................................................................................................................6 b. Textile ...........................................................................................................................................7 c. Construction..................................................................................................................................8