Quality in Higher Education: Global Perspectives and Best Practices‖

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Repeaters First Timers School Performance Of

The performance of schools in the September 2018 Registered Electrical Engineer Licensure Examination in alphabetical order as per R.A. 8981 otherwise known as PRC Modernization Act of 2000 Section 7(m) "To monitor the performance of schools in licensure examinations and publish the results thereof in a newspaper of national circulation" is as follows: SEPTEMBER 2018 R. E. E. LICENSURE EXAMINATION PERFORMANCE OF SCHOOLS IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER SEQ. FIRST TIMERS REPEATERS OVERALL PERFORMANCE NO. SCHOOL PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED PASSED FAILED COND TOTAL % PASSED ABE INTERNATIONAL COLLEGE 1 OF BUSINESS & ECONOMICS- 1 0 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% BACOLOD ABRA STATE INST. OF SCIENCE & 2 TECH.(ABRA IST)-BANGUED 3 7 0 10 30.00% 1 2 0 3 33.33% 4 9 0 13 30.77% ADAMSON UNIVERSITY 3 29 7 0 36 80.56% 2 8 0 10 20.00% 31 15 0 46 67.39% ADVENTIST INTERNATIONAL 4 INSTITUTE OF ADVANCED 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% STUDIES AGUSAN BUSINESS & ART 5 FOUNDATION, INC. 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% ALDERSGATE COLLEGE 6 1 1 0 2 50.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 1 2 0 3 33.33% ALEJANDRO COLLEGE 7 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% AMA COMPUTER COLLEGE- 8 ZAMBOANGA CITY 0 1 0 1 0.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 0 1 0 1 0.00% ANDRES BONIFACIO COLLEGE 9 6 3 0 9 66.67% 0 3 0 3 0.00% 6 6 0 12 50.00% ANTIPOLO SCHOOL OF NURSING 10 & MIDWIFERY 1 0 0 1 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 1 0 0 1 100.00% ATENEO DE DAVAO UNIVERSITY 11 3 0 0 3 100.00% 0 0 0 0 0.00% 3 0 0 3 100.00% AURORA STATE COLLEGE OF 12 TECHNOLOGY 12 2 -

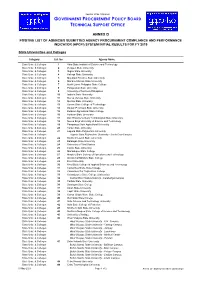

State Universities and Colleges

Republic of the Philippines GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT POLICY BOARD TECHNICAL SUPPORT OFFICE ANNEX D POSITIVE LIST OF AGENCIES SUBMITTED AGENCY PROCUREMENT COMPLIANCE AND PERFORMANCE INDICATOR (APCPI) SYSTEM INITIAL RESULTS FOR FY 2019 State Universities and Colleges Category Cat. No. Agency Name State Univ. & Colleges 1 Abra State Institute of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 2 Benguet State University State Univ. & Colleges 3 Ifugao State University State Univ. & Colleges 4 Kalinga State University State Univ. & Colleges 5 Mountain Province State University State Univ. & Colleges 6 Mariano Marcos State University State Univ. & Colleges 7 North Luzon Philippine State College State Univ. & Colleges 8 Pangasinan State University State Univ. & Colleges 9 University of Northern Philippines State Univ. & Colleges 10 Isabela State University State Univ. & Colleges 11 Nueva Vizcaya State University State Univ. & Colleges 12 Quirino State University State Univ. & Colleges 13 Aurora State College of Technology State Univ. & Colleges 14 Bataan Peninsula State University State Univ. & Colleges 15 Bulacan Agricultural State College State Univ. & Colleges 16 Bulacan State University State Univ. & Colleges 17 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University State Univ. & Colleges 18 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology State Univ. & Colleges 19 Pampanga State Agricultural University State Univ. & Colleges 20 Tarlac State University State Univ. & Colleges 21 Laguna State Polytechnic University State Univ. & Colleges Laguna State Polytechnic University - Santa Cruz Campus State Univ. & Colleges 22 Southern Luzon State University State Univ. & Colleges 23 Batangas State University State Univ. & Colleges 24 University of Rizal System State Univ. & Colleges 25 Cavite State University State Univ. & Colleges 26 Marinduque State College State Univ. & Colleges 27 Mindoro State College of Agriculture and Technology State Univ. -

State Universities and Colleges 963 R

STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES 963 R. BANGSAMORO AUTONOMOUS REGION IN MUSLIM MINDANAO (BARMM) R.1. ADIONG MEMORIAL POLYTECHNIC STATE COLLEGE For general administration and support, support to operations, and operations, including locally-funded project(s), as indicated hereunder....................................................................................................................P 155,730,000 ============= New Appropriations, by Program ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Current Operating Expenditures ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ Maintenance and Other Personnel Operating Capital Services Expenses Outlays Total ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ PROGRAMS 100000000000000 General Administration and Support P 10,597,000 P 14,495,000 P P 25,092,000 200000000000000 Support to Operations 2,000 840,000 29,153,000 29,995,000 300000000000000 Operations 18,863,000 13,594,000 68,186,000 100,643,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ HIGHER EDUCATION PROGRAM 18,863,000 7,411,000 68,186,000 94,460,000 ADVANCED EDUCATION PROGRAM 574,000 574,000 RESEARCH PROGRAM 1,872,000 1,872,000 TECHNICAL ADVISORY EXTENSION PROGRAM 3,737,000 3,737,000 ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ TOTAL NEW APPROPRIATIONS P 29,462,000 P 28,929,000 P 97,339,000 P 155,730,000 ================ ================ ================ ================ New Appropriations, by Programs/Activities/Projects (Cash-Based) ¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯¯ -

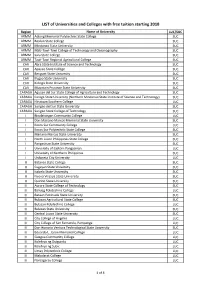

LIST of Universities and Colleges with Free Tuition Starting 2018

LIST of Universities and Colleges with free tuition starting 2018 Region Name of University LUC/SUC ARMM Adiong Memorial Polytechnic State College SUC ARMM Basilan State College SUC ARMM Mindanao State University SUC ARMM MSU-Tawi-Tawi College of Technology and Oceanography SUC ARMM Sulu State College SUC ARMM Tawi-Tawi Regional Agricultural College SUC CAR Abra State Institute of Science and Technology SUC CAR Apayao State College SUC CAR Benguet State University SUC CAR Ifugao State University SUC CAR Kalinga State University SUC CAR Mountain Province State University SUC CARAGA Agusan del Sur State College of Agriculture and Technology SUC CARAGA Caraga State University (Northern Mindanao State Institute of Science and Technology) SUC CARAGA Hinatuan Southern College LUC CARAGA Surigao del Sur State University SUC CARAGA Surigao State College of Technology SUC I Binalatongan Community College LUC I Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University SUC I Ilocos Sur Community College LUC I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College SUC I Mariano Marcos State University SUC I North Luzon Philippines State College SUC I Pangasinan State University SUC I University of Eastern Pangasinan LUC I University of Northern Philippines SUC I Urdaneta City University LUC II Batanes State College SUC II Cagayan State University SUC II Isabela State University SUC II Nueva Vizcaya State University SUC II Quirino State University SUC III Aurora State College of Technology SUC III Baliuag Polytechnic College LUC III Bataan Peninsula State University SUC III Bulacan Agricultural State College SUC III Bulacan Polytechnic College LUC III Bulacan State University SUC III Central Luzon State University SUC III City College of Angeles LUC III City College of San Fernando, Pampanga LUC III Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University SUC III Eduardo L. -

Ÿþc M O 9 S 2 0 1 9 S U C L E V E L O F 1 0 6 S U

HIGII ,‘ Republic of the Philippines 01.N on High C/) OFFICE OF THE PRESIDENT 0 COMMISSION ON HIGHER EDUCATION foFFIcIAL. e RELEASE 13 CHED Central Office Cl CHED Memorandum Order RECORDS SECTION No. 09 tzy Series of 2019 e., U.r. GO\ Subject : SUC LEVEL OF 106 STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES In accordance with the pertinent provisions of Republic Act (RA) No. 7722, otherwise known as the "Higher Education Act of 1994" and Republic Act (RA) No. 8292, otherwise known as the "Higher Education Modernization Act of 1997", pursuant to Joint Circular No. 1, s. 2016, otherwise known as the "FY 2016 Levelling Instrument for SUCs and Guidelines for the Implementation Thereof," and National Evaluation Committee (NEC) Resolution Nos. 1 and 2, s. 2019, the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) hereby issues the following: I. List of SUCs with their corresponding levels pursuant to CM° 12, s. 2018 titled "2016 SUC Levelling Results, SUC Levelling Benefits and SUC Levelling Appeal Procedures" effective August 20, 2018: No. Region State University / College SUC LEVEL 1 I Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College III 2 I Mariano Marcos State University IV 3 I North Luzon Philippines State College I 4 I Pangasinan State University IV 5 II Batanes State College I 6 II Cagayan State University III 7 II Isabela State University IV 8 ll Nueva Vizcaya State University IV 9 II Quirino State University II 10 III Aurora State College of Technology II 11 III Bataan Peninsula State University III 12 III Bulacan Agricultural State College III 13 III Central Luzon State -

FOI Manuals/Receiving Officers Database

State Universities and Colleges (SUCs) Acronym Agency Office/Unit/Department Address Name of Receiving Officer Telephone nos. Email Address FOI Manuals Link AIST Abra Institute of Science and Technology* http://www.asist.edu.ph/asistfoi.pdf AMPC Adiong Memorial Polytechnic College*** No Manual https://asscat.edu.ph/? Agusan Del Sur State College of Agriculture page_id=15#1515554207183-ef757d4a-bbef ASSCAT Office of the AMPC President Cristina P. Domingo 9195168755 and Technology http://asscat.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/FOI. pdf https://drive.google. ASU Aklan State University* com/file/d/0B8N4AoUgZJMHM2ZBVzVPWDVDa2M/ view ASC Apayao State College*** No Manual http://ascot.edu.ph/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/FOI. pdf ASCOT Aurora State College of Technology* cannot access site BSC Basilan State College*** No Manual http://www.bpsu.edu.ph/index.php/freedom-of- BPSU Bataan Peninsula State University* information/send/124-freedom-of-information- manual/615-foi2018 BSC Batanes State College* http://www.bscbatanes.edu.ph/FOI/FOI.pdf BSU Batangas State University* http://batstate-u.edu.ph/transparency-seal-2016/ 1st floor, University Public Administration Kara S. Panolong 074 422 2402 loc. 69 [email protected] Affairs Office Building, Benguet State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Administration Kenneth A. Laruan 63.74.422.2127 loc 16 President for [email protected] Building, Benguet Academic Affairs State University http://www.bsu.edu.ph/files/PEOPLE'S% BSU Benguet State University Office of the Vice 2nd floor, 20Manual-foi.pdf President for Administration Alma A. Santiago 63-74-422-5547 Research and Building, Benguet Extension State University 2nd floor, Office of the Vice Marketing Sheryl I. -

Table 8. State Universities and Colleges Number of Faculty by Program Level: AY 2019-20

Table 8. State Universities and Colleges Number of Faculty by Program Level: AY 2019-20 GAA Region SUC Main BA/BS/B MA/MS/M Ph.D. Grand Total Ilocos Region Don Mariano Marcos Memorial State University 220 304 129 653 Ilocos Sur Polytechnic State College 78 139 60 277 Mariano Marcos State University 206 229 102 537 North Luzon Philippines State College 28 50 15 93 Pangasinan State University 267 292 156 715 University of Northern Philippines 194 232 90 516 Cagayan Valley Batanes State College 13 23 - 36 Cagayan State University 338 455 208 1,001 Isabela State University 356 491 135 982 Nueva Vizcaya State University 177 147 67 391 Quirino State University 98 116 27 241 Central Luzon Aurora State College of Technology 55 33 18 106 Bataan Peninsula State University 119 226 118 463 Bulacan Agricultural State College 80 65 23 168 Bulacan State University 728 512 89 1,329 Central Luzon State University 161 226 114 501 Don Honorio Ventura Technological State University 299 162 37 498 Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology 255 359 108 722 Pampanga State Agricultural University 44 125 43 212 Philippine Merchant Marine Academy 44 20 4 68 President Ramon Magsaysay State University 242 102 40 384 Tarlac Agricultural University 69 75 43 187 Tarlac State University 186 150 79 415 CALABARZON Batangas State University 490 260 222 972 Cavite State University 990 384 134 1,508 Laguna State Polytechnic University 460 286 138 884 Southern Luzon State University 96 144 81 321 University of Rizal System 207 266 149 622 Bicol Region Bicol State College of Applied Sciences and Technology 62 53 19 134 Bicol University 321 326 138 785 Camarines Norte State College 104 103 33 240 Camarines Sur Polytechnic Colleges 87 74 27 188 Catanduanes State University 133 109 59 301 Central Bicol State University of Agriculture 211 127 90 428 Dr. -

Higher Education in ASEAN

Higher Education in ASEAN © Copyright, The International Association of Universities (IAU), October, 2016 The contents of the publication may be reproduced in part or in full for non-commercial purposes, provided that reference to IAU and the date of the document is clearly and visibly cited. Publication prepared by Stefanie Mallow, IAU Printed by Suranaree University of Technology On the occasion of Hosted by a consortium of four Thai universities: 2 Foreword The Ninth ASEAN Education Ministers Qualifications Reference Framework (AQRF) Meeting (May 2016, in Malaysia), in Governance and Structure, and the plans to conjunction with the Third ASEAN Plus institutionalize the AQRF processes on a Three Education Ministers Meeting, and voluntary basis at the national and regional the Third East Asia Summit of Education levels. All these will help enhance quality, Ministers hold a number of promises. With credit transfer and student mobility, as well as the theme “Fostering ASEAN Community of university collaboration and people-to-people Learners: Empowering Lives through connectivity which are all crucial in realigning Education,” these meetings distinctly the diverse education systems and emphasized children and young people as the opportunities, as well as creating a more collective stakeholders and focus of coordinated, cohesive and coherent ASEAN. cooperation in education in ASEAN and among the Member States. The Ministers also The IAU is particularly pleased to note that the affirmed the important role of education in Meeting approved the revised Charter of the promoting a better quality of life for children ASEAN University Network (AUN), better and young people, and in providing them with aligned with the new developments in ASEAN. -

BU Hosts PASUC National Culture and the Arts Festival 2015

ISSN 2094-3991 Special Issue 01 NOVEMBER 2015 Torch of Wisdom. Bicol University, the premier state university in the Bicol Region, was chosen as this year’s host of the 7th Philippine Association of State Universities and Colleges (PASUC) National Culture and the Arts Festival. (Photo courtesy of: Earl Epson L. Recamunda/OP) Mascariñas BU hosts PASUC National Culture welcomes and the Arts Festival 2015 PASUC At least 2,500 delegates from 112 State Universities and in the country composed delegates Colleges (SUC’s) will be taking part in the 7th Philippine of administrators, coaches, Bicol University Association of State Universities and Colleges (PASUC) trainers and student- heartily welcomes all the National Culture and the Arts Festival which will be participants to compete of the different state held at Bicol University (BU), Legazpi City, Albay on in the 24 cultural-artistic delegatesuniversities andand collegesofficials November 30 to December 2, 2015. throughout the country to the 7th Philippine association of public of this year’s festival. With Presidentevents in five Dr. major Ricardo venues. E. tertiary PASUC,institutions in thean theand BUtheme, to be the“Transforming official host Rotoras, Headed in-cooperation by PASUC Universities and Colleges Philippines which includes the Landscape of Culture Association of State all state universities and the Arts in the President Dr. Modesto and the Arts Festival! with PASUC Regional (PASUC) We National are proud Culture to and colleges under the Public Higher Education have been chosen -

Philippine Society for the Study of Nature (PSSN), Inc. TIN 005-866-117-000 SEC Reg

ICONSIE 2016 “Nature Studies: Creating knowledge and building bridges for resiliency and sustainability” 1 Philippine Society for the Study of Nature (PSSN), Inc. TIN 005-866-117-000 SEC Reg. No. B200000647 Mailing Address: P.O box 1036, Baguio City, Benguet, Philippines Website: http://www.psssnonline.org Philippine Society for the Study of Nature, Inc. BPI checking account no. 000911-0146-45 Los Baños Branch PSSN stands for the Philippine Society for the Study of Nature, Inc. It was organized in a national conference on networking for the wise and sustainable use of nature at the University of the Philippines College Baguio (now University of the Philippines Baguio) in April 2000. The participants saw the need for a network to address nature and nature- related problems on the country. Thus, the society was established in order to provide a venue for the development pf strategies for the unscrupulous utilization of nature and its amenities. On September 16, 2000, the society was registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) as a non-profit, non-stock, non-partisan organization of Professionals, researchers, administration policymakers, practitioners, students, and organizations involved in nature studies and its related activities. The society’s primary objectives are to provide and develop strategies towards wise and sustainable use of nature and to ensure a faithful representation of responsible thinking and sentiment regarding issues about nature. It also seeks to established partnership and/ or collaboration with local government units and other institutions that are involved in the development, conservation, and management of nature resources, Its various activities serve as a channel for the exchange of information, sharing of professionals expertise, networking, and strengthening of camaraderie and cooperation among members and partner’s institutions. -

No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No

ANNEX B * STATE UNIVERSITIES AND COLLEGES No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address No. School Campus / Address Polytechnic University of the 1 Bataan Peninsula State University All Campuses 20 Eastern Visayas State University All Campuses 39 All Campuses Philippines Ramon Magsaysay Technological 2 Batangas State University All Campuses 21 Ifugao State University All Campuses 40 All Campuses University 3 Benguet State University All Campuses 22 Isabela State University All Campuses 41 Rizal Technological University All Campuses 4 Bicol University All Campuses 23 Kalinga-Apayao State College All Campuses 42 Samar State University All Campuses 5 Bukidnon State University All Campuses 24 Leyte Normal University All Campuses 43 Sultan Kudarat State University All Campuses 6 Bulacan State University All Campuses 25 Mariano Marcos State University All Campuses 44 Tarlac College of Agriculture All Campuses Mindanao University of Science and 7 Cagayan State University All Campuses 26 All Campuses 45 Tarlac State University All Campuses Technology Mt. Province State Polytechnic Technological University of the 8 Camarines Sur Polytechnic College All Campuses 27 All Campuses 46 All Campuses College Philippines 9 Capiz State University All Campuses 28 Naval State University All Campuses 47 University of Antique All Campuses 10 Catanduanes State College All Campuses 29 Negros Oriental State University All Campuses 48 University of Eastern Philippines All Campuses 11 Cavite State University All Campuses 30 Northwest Samar State University -

Date May 2 5 2018

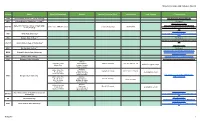

Republika ng Pilipinas KAGAWARAN NG KATARUNGAN Department of Justice 'tt Manila MIG-DC DEPARTMENT CIRCULAR NO. 02 n TO : Undersecretaries/Assistant Secretaries All Heads of Bureaus, Commissions and Offices attached to the Department Chiefs of Service/Staff In the Office of the Secretary All Concerned SUBJECT : GSIS Scholarship Program for Academic Year 2018-2019 date may 2 5 2018 Attached is a letter dated 02 May 2018 from the President and General Manager, Government Service Insurance System (GSIS) inviting applicants to the GSIS Scholarship Program (GSP)for Academic Year 2018-2019. The GSP is open to qualified members and Permanent Total Disability (PTD) pensioners below 60 years old who have incoming college children/dependents accepted or enrolled in any four-or five-year college course or priority course (Annex A) identified by the Commission on Higher Education (CHED) in a higher educational institution that has its own charter or a school qualified by the CHED as Level IV and III, autonomous, or with a deregulated status (Annex B). Qualified members who may apply include active and regular GSIS members who have salary grades 24 and below, or its equivalent job level. Deadline for submission of application will be on 15 June 2018. Details of the program are contained in the attached factsheet. Application forms may be downloaded from the GSIS website, www.gsis.gov.ph. For information, guidance and appropriate action. MENARDO I. GUEVARRA Secretary Department o' Justice Ct^;020180S276 I ^Government Service Insurance System I Financial Center, Pasay City, Metro Manila 1308 2 May 2018 OFftefi qr tHE SECRETAnV ,, , ' Acting Sec.