American Music Review the H

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booklet-Gobs.Pdf

I like to ute, ute, ute puppurunu Nah,And nah, hope n-n-n-n-nah we’ll meet again(8x) each other. We can create the fun Stomping in the puddles on a 1. Imaginationpuzzu . tomorrow by using our imagnations to move us rainy day “Your attention please. The fun Verse - Make fists and alternate tapping them on Dancing to my favorite song takes the begins now!” Gobs of fun and gobs of goo topWords of each & Music other, then point to your brain, Children'sblues away Vocals Activity Suggestions “This just in. Kids can have fun by simply Words & Music by Stephen Fite Abigail Inyang, Jackie McCarthy Nah, nah, n-n-n-n-nah Here’s the wish I wish for you and then extend one fist and arm into the Makin‚ a milk mustache on my lip using their imaginations.” Additional words to Pepperoni Pizza DJ Argenziano, Addi Berry Nah,This isnah, a variation n-n-n-n-nah on the tune, Apples & That you might rise above the stars air. Encourage the children to join the kids Travelin’ with my family on a great written Stephen Fite Emily Berry, Annabeth Berry Nah,Bananas. nah, n-n-n-n-nahAs a class project, see Nah,And nah, be who n-n-n-n-nah you are (8x) on the CD in asking When, Where, Who, vacation trip Arranged & Produced by Nah,how manynah, nah, other n-n-n-n-nah, foods will work nah with the What & Why. These are just a few of the things I like Verse Nah,melody nah, and n-n-n-n-nah rhythm of this song. -

Vol LI Issue 1

page 2 the paper january 31, 2018 Marc Molinaro, pg. 3 Hygge, pg. 9 Oscars, pg. 15 F & L, pg. 21-22 Earwax, pg. 23 the paper “Favorite U.S. President Based on Looks” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University Colleen “Barack Obama” Burns Bronx, NY 10458 Claire “John Tyler” Nunez [email protected] Executive Editor http://fupaper.blog/ Michael Jack “Lyndon Baines Johnson” O’Brien News Editors the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all Christian “Theodore Roosevelt” Decker years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Andrew “Rutherford B. Hayes” Millman Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Opinions Editors Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- Jack “Millard Fillmore” Archambault ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Hillary “Franklin Daddy Roosevelt” Bosch students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their Arts Editors thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Meredith “Spiro Agnew” McLaughlin have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Annie “Dead White Guy” Muscat the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone Earwax Editor who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Marty “Andrew Jackson” Gatto mail or come to our next meeting. -

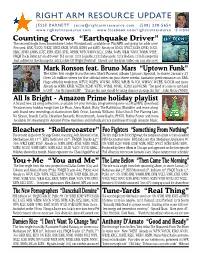

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 12/10/2014 Counting Crows “Earthquake Driver” The second single from Somewhere Under Wonderland, available on PlayMPE and going for adds now! First week: KINK, WCOO, WEZZ, WEXT, KROK, WVOD, KOHO and KMTN Already on WNCS, WWCT, KCSN, KPND, WJCU, KBAC, KFMU, KMMS, KOZT, KSPN, KTAO, KYSL, WEHM, WFIV, WMWV, KCLC, KNBA, WAPS, WBJB, WMVY, WNRN, WYEP... FMQB Tracks Debut 44* on add week! Still on tour: 12/10 Louisville, 12/12 Indianapolis, 12/13 Madison, 12/16 Davenport IA Just added to the lineup for 2015’s Isle Of Wight Festival! Check out the lyric video on our site now Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars “Uptown Funk” The killer first single from the new Mark Ronson album Uptown Special, in stores January 27 Over 20 million views for the official video in just three weeks, fantastic performance on SNL Huge adds this week from WFUV, WXPN, WWNU, WRSI, WBJB, WJCU, WMWV, WCBE, WOCM and more Already on WXRV, KRVB, WZEW, KCMP, WFPK, WYMS, WNKU, KOHO and WCNR “Too good of a tune to just hand to CHR” - Jim McGuinn/KCMP “Stations like ours should be taking chances on songs like this” - John McGue/WNKU All Is Bright - Amazon Prime holiday playlist A brand new 43 song collection, available for your holiday programming now via PlayMPE download Features new holiday songs from Liz Phair, Anna Nalick, Ruby The Rabbitfoot, Blondfire and more along with brand new recordings of classics from Beth Orton, Lucinda Williams, Yoko Ono & The Flaming Lips, No Sinner, Brandi Carlile, Heartless Bastards, Houndmouth, Jessie Baylin, PHOX, Ruthie Foster and more Available for streaming for Amazon Prime members and individual track purchases through Amazon Music Bleachers “Rollercoaster” Foo Fighters “Something From Nothing” The second single from Strange Desire, featuring Jack Antonoff of fun. -

Adjective Adjective Noun Verb Adverb Prepositional Phrase

!"##$%&dd+d)*dr/*&d012)3,*4&*45*)65#5+$78)9::;))r54$d)9:>>?))))))))))))))))))))Volume 1) FRAME SAMPLE (page #) “Here, There” (McCrackens.1980s; M. Brechtel) Salmon Here, Salmon There (54) Colonies Here, Colonies There (54) Pigs Here, Pigs There (54) HERE, THERE (Blank Frame) (54) “Yes, Ma‛am” (Ella Jenkins. Call-Response. 1968) Trophic Levels Yes, Ma‛am (55) Yes, Ma‛am (Blank Frame) (55) Parts of Speech Yes, Ma‛am (56) “I Know A…” I Know A Seahorse (57) I Know An Unusual Ecosystem (57) (Adapted from Peter, Paul & Mary lyrics, 1960‛s) I Know A Meteorologist (57) I Know An Unusual Fish (57) I Know an Unusual Number (57) Marine Cadence (Jodys/ Sound Off. 1944.) California Gold Rush (58) Geography Alive! (59) Starch And Protein Sound-Off (58) American Civilization Cadence (59) Canoe Sound-Off (58) Washington State (60) “Twelve Days of Christmas” (Epiphany: 14-16th C) 12 Days in Gold Rush (61) 12 Days in Medieval Times (61) 12 Days in Arkansas (61) Constitutional Amendments (62-63) “Bugaloo” (Boogaloo. 1966. R.Ray/B.Cruz; A. Brechtel)) Crustacean Bugaloo (64) Egyptian Mummy Bugaloo (65) Aboriginal Life Bugaloo (64) I‛m a Greek God Bugaloo(66) “Johnny Comes Marching Home” (P.S. Gilmore (Civil War), 1863) Solid Shapes Are Everywhere (66) Greeks Go Marching (67) “Nah, Nah, Nah, Nah…” (Steam. 1969.) Scientific Investigation (68) Dolphins In Captivity (69) Others: Pharaoh Song (70) I‛m A Greek 2-3-4 (70) Prepositions (71) Polygon Chant (69) Florist Chant (67) Verbs of Being (71) Plumber Chant (63) Little Insect Egg (71) Ant/ Insect (71) Access the Core-Level 1 Workbook/AMF.2008 (Revised 4-11) 53 HERE, THERE SALMON HERE, SALMON THERE COLONIES HERE, COLONIES THERE PIGS HERE, PIGS THERE By Ana Filipek. -

BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne

BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne David Byrne, Nelly Furtado, How to Dress Well, Devonté Hynes, Kelis, Nico Muhly + Ira Glass, St. Vincent, tUnE-yArDs and ten color guard teams from North America all perform LIVE Contemporary Color marks BAM’s first production partnership with Barclays Center, a historic pairing of performing arts institution and major arena June 27 & 28 at Barclays Center for BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season June 22 & 23 at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre for Luminato Festival Bloomberg Philanthropies is the 2014/2015 Season Sponsor BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color Conceived by David Byrne Barclays Center (620 Atlantic Ave) Jun 27 & 28 at 7:30PM Tickets start at $25 On sale Jan 28 to general public (Jan 21 to Friends of BAM) Brooklyn, NY/Jan 21, 2015— BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, a performance event created by music icon David Byrne, co-commissioned by BAM and Toronto’s Luminato Festival, and inspired by the high school phenomenon of color guard, known as “the sport of the arts.” Ten 20-40 person color guard teams from the US and Canada will perform at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center and Toronto’s Air Canada Centre, alongside an extraordinary array of musical talent performing live. Contemporary Color is the artistic culmination of Byrne’s interest in color guard as a piece of Americana and a competitive art form. When Byrne agreed to lend a composition to a high school performance team back in 2008, he knew little about the color guard phenomenon, which is wildly popular in high schools across the North American continent. -

Stacia Yearwood Yearwood 2

Yearwood 1 Like Salt Water¼ A Memoir Stacia Yearwood Yearwood 2 For my Family- Those who have gone before me, Those who Live now, And those who will come to cherish these words in the future¼. Yearwood 3 Proem Not, in the saying of you, are you said. Baffled and like a root stopped by a stone you turn back questioning the tree you feed. But what the leaves hear is not what the roots ask. Inexhaustibly, being at one time what was to be said and at another time what has been said the saying of you remains the living of you never to be said. But, enduring, you change with change that changes and yet are not of the changing of any of you. Ever yourself, you are always about to be yourself in something else ever with me. Yearwood 4 Martin Carter (1927-1997) CONTENTS_______________________________________________________ FOREWORD page 5 HOPE FLOATS- A JOURNAL ENTRY page 8 SOJOURNING page 10 A LONG TIME AGO- THE ANCESTORS page 12 DIANA page 25 EYE WASH page 27 PARALYSIS page 32 NERVES page 35 TO REMOVE SEA WATER FROM THE EARS page 41 SHINGLES page 46 HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE page 50 RASHES AND ITCHES page 55 MALARIA FEVER page 58 STROKE page 61 HEART TROUBLES page 68 INDIFFERENT FEELINGS page 72 Yearwood 5 SUNBURN page 79 SCARS AND BITES page 83 LAST JOURNAL ENTRY page 87 Foreword Four rainy seasons ago I wrote in my journal: “I hope this place doesn’t change me.” But I have come to understand that just as culture is fluid, so are the personality and identity malleable. -

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2Pac Thug Life

Recording Artist Recording Title Price 2pac Thug Life - Vol 1 12" 25th Anniverary 20.99 2pac Me Against The World 12" - 2020 Reissue 24.99 3108 3108 12" 9.99 65daysofstatic Replicr 2019 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest We Got It From Here Thank You 4 Your Service 12" 20.99 A Tribe Called Quest People's Instinctive Travels And The Paths Of Rhythm 12" Reissue 26.99 Abba Live At Wembley Arena 12" - Half Speed Master 3 Lp 32.99 Abba Gold 12" 22.99 Abba Abba - The Album 12" 12.99 AC/DC Highway To Hell 12" 20.99 Ace Frehley Spaceman - 12" 29.99 Acid Mothers Temple Minstrel In The Galaxy 12" 21.99 Adele 25 12" 16.99 Adele 21 12" 16.99 Adele 19- 12" 16.99 Agnes Obel Myopia 12" 21.99 Ags Connolly How About Now 12" 9.99 Air Moon Safari 12" 15.99 Alan Marks Erik Satie - Vexations 12" 19.99 Aldous Harding Party 12" 16.99 Alec Cheer Night Kaleidoscope Ost 12" 14.99 Alex Banks Beneath The Surface 12" 19.99 Alex Lahey The Best Of Luck Club 12" White Vinyl 19.99 Algiers There Is No Year 12" Dinked Edition 26.99 Ali Farka Toure With Ry Cooder Talking Timbuktu 12" 24.99 Alice Coltrane The Ecstatic Music Of... 12" 28.99 Alice Cooper Greatest Hits 12" 16.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" Dinked Edition 19.99 Allah Las Lahs 12" 18.99 Alloy Orchestra Man With A Movie Camera- Live At Third Man Records 12" 12.99 Alt-j An Awesome Wave 12" 16.99 Amazones D'afrique Amazones Power 12" 24.99 American Aquarium Lamentations 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Amy Winehouse Frank 12" 19.99 Amy Winehouse Back To Black - 12" 12.99 Anchorsong Cohesion 12" 12.99 Anderson Paak Malibu 12" 21.99 Andrew Bird My Finest Work 12" 22.99 Andrew Combs Worried Man 12" White Vinyl 16.99 Andrew Combs Ideal Man 12" Colour Vinyl 16.99 Andrew W.k I Get Wet 12" 38.99 Angel Olsen All Mirrors 12" Clear Vinyl 22.99 Angelo Badalamenti Twin Peaks - Ost 12" - Ltd Green 20.99 Ann Peebles Greatest Hits 12" 15.99 Anna Calvi Hunted 12" - Ltd Red 24.99 Anna St. -

Your Speaking Voice

YOUR SPEAKING VOICE Tips for Adding Strength and WHERE LEADERS Authority to Your Voice ARE MADE YOUR SPEAKING VOICE TOASTMASTERS INTERNATIONAL P.O. Box 9052 • Mission Viejo, CA 92690 • USA Phone: 949-858-8255 • Fax: 949-858-1207 www.toastmasters.org/members © 2011 Toastmasters International. All rights reserved. Toastmasters International, the Toastmasters International logo, and all other Toastmasters International trademarks and copyrights are the sole property of Toastmasters International and may be used only with permission. WHERE LEADERS Rev. 6/2011 Item 199 ARE MADE CONTENTS The Medium of Your Message........................................................................... 3 How Your Voice Is Created .............................................................................. 4 Breath Produces Voice ............................................................................... 4 Production of Voice Quality.......................................................................... 4 What Kind of Voice Do You Have? ....................................................................... 5 Do You Whisper or Boom? ........................................................................... 5 Are You Monotonous or Melodious? ................................................................. 5 Is Your Voice a Rain Cloud or a Rainbow? ............................................................. 5 Do You Have Mumblitis? ............................................................................. 5 How Well Do You Articulate?........................................................................ -

JOHNNY GONZALEZ, with IRMA NÚÑEZ INTERVIEWED by KAREN MARY DAVALOS on OCTOBER 28, NOVEMBER 4, 11, and 18, and DECEMBER 17 and 20, 2007

CSRC ORAL HISTORIES SERIES NO. 7, NOVEMBER 2013 JOHNNY GONZALEZ, with IRMA NÚÑEZ INTERVIEWED BY KAREN MARY DAVALOS ON OCTOBER 28, NOVEMBER 4, 11, AND 18, AND DECEMBER 17 AND 20, 2007 Artist and businessman Johnny/Don Juan Gonzalez is recognized as one of the founders of the Chicano Mural Movement in East Los Angeles. He co-founded the Goez Art Studios and Gallery in 1969. His mural designs include those for Story of Our Struggle and The Birth of Our Art. A resident of Los Angeles, Gonzalez is a partner in Don Juan Productions, Advertising, and Artistic Services. Educator Irma Núñez has taught in the Los Angeles Unified School District and has been involved in citywide adult education programs. She is the recipient of the CALCO Excellence in Teaching Award from the California Council for Adult Education. She is a partner in Don Juan Productions, Advertising, and Artistic Services. Karen Mary Davalos is chair and professor of Chicana/o studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. Her research interests encompass representational practices, including art exhibition and collection; vernacular performance; spirituality; feminist scholarship and epistemologies; and oral history. Among her publications are Yolanda M. López (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2008); “The Mexican Museum of San Francisco: A Brief History with an Interpretive Analysis,” in The Mexican Museum of San Francisco Papers, 1971–2006 (UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center Press, 2010); and Exhibiting Mestizaje: Mexican (American) Museums in the Diaspora (University of New Mexico Press, 2001). This interview was conducted as part of the L.A. Xicano project. -

Billboard Magazine

Pop's princess takes country's newbie under her wing as part of this season's live music mash -up, May 31, 2014 1billboard.com a girl -powered punch completewith talk of, yep, who gets to wear the transparent skirt So 99U 8.99C,, UK £5.50 SAMSUNG THE NEXT BIG THING IN MUSIC 200+ Ad Free* Customized MINI I LK Stations Radio For You Powered by: Q SLACKER With more than 200 stations and a catalog of over 13 million songs, listen to your favorite songs with no interruption from ads. GET IT ON 0)*.Google play *For a limited time 2014 Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC. Samsung and Milk Music are both trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. Appearance of device may vary. Device screen imagessimulated. Other company names, product names and marks mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners and may be trademarks or registered trademarks. Contents ON THE COVER Katy Perry and Kacey Musgraves photographed by Lauren Dukoff on April 17 at Sony Pictures in Culver City. For an exclusive interview and behind-the-scenes video, go to Billboard.com or Billboard.com/ipad. THIS WEEK Special Double Issue Volume 126 / No. 18 TO OUR READERS Billboard will publish its next issue on June 7. Please check Billboard.biz for 24-7 business coverage. Kesha photographed by Austin Hargrave on May 18 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. FEATURES TOPLINE MUSIC 30 Kacey Musgraves and Katy 5 Can anything stop the rise of 47 Robyn and Royksopp, Perry What’s expected when Spotify? (Yes, actually.) Christina Perri, Deniro Farrar 16 a country ingenue and a Chart Movers Latin’s 50 Reviews Coldplay, pop superstar meet up on pop trouble, Disclosure John Fullbright, Quirke 40 “ getting ready for tour? Fun and profits. -

BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne

BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, Conceived by David Byrne David Byrne, Nelly Furtado, How to Dress Well, Devonté Hynes, Zola Jesus, Lucius, Money Mark + Ad-Rock, Nico Muhly + Ira Glass, St. Vincent, tUnE-yArDs, and ten color guard teams from North America all perform LIVE Art Direction & Design by Doyle Partners; photo by Julieta Cervantes Contemporary Color marks BAM’s first production partnership with Barclays Center, a historic pairing of performing arts institution and major arena June 27 & 28 at Barclays Center for BAM 2015 Winter/Spring Season June 22 & 23 at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre for Luminato Festival Bloomberg Philanthropies is the 2014/2015 Season Sponsor BAM and Barclays Center Present Contemporary Color Conceived by David Byrne Barclays Center (620 Atlantic Ave) Jun 27 & 28 at 7:30PM Tickets start at $25 On sale Jan 28 to general public (Jan 21 to Friends of BAM) Brooklyn, NY/updated May 14, 2015— BAM and Barclays Center present Contemporary Color, a performance event created by music icon David Byrne, co-commissioned by BAM and Toronto’s Luminato Festival, and inspired by the high school phenomenon of color guard, known as “the sport of the arts.” Ten 20-40 person color guard teams from the US and Canada will perform at Brooklyn’s Barclays Center and Toronto’s Air Canada Centre, alongside an extraordinary array of musical talent performing live. Artist and team parings can be found below. Contemporary Color is the artistic culmination of Byrne’s interest in color guard as a piece of Americana and a competitive art form. -

Midnight Train to Georgia

American Music Review The H. Wiley Hitchcock Institute for Studies in American Music Conservatory of Music, Brooklyn College of the City University of New York Volume XLIII, Number 2 Spring 2014 “The Biggest Feminist in the World”: On Miley Cyrus, Feminism, and Intersectionality1 Alexandra Apolloni, UCLA On 14 November 2013 Miley Cyrus proclaimed her feminism to an unsuspecting world. “I feel like I’m one of the biggest feminists in the world because I tell women not to be scared of anything,” she said. “Girls are beau- tiful. Guys get to show their titties on the beach, why can’t we?”2 For a media-friendly soundbite, this quota- tion actually reveals a lot about a phenomenon that, for simplicity’s sake, I’m going to refer to as Miley feminism. Miley feminism is about fearless- ness: about being unafraid to make choices, to be yourself, to self-express. It’s about appropriating a masculine-coded kind of individual freedom: the freedom to not care, to show your titties on the beach, to party without con- sequences, to live the “can’t stop won’t stop” dream that Cyrus sang about in “We Can’t Stop,” the arresting pop anthem that was inescapable during the summer of 2013. This feminism is transgressive, up to a point: Miley imagines a kind of femininity that flagrantly rejects the rules of respect- ability and propriety that define normative notions of girlhood. Miley’s not the only one singing the song of this type of feminism: we could be talking about Ke$ha feminism—Ke$ha’s laissez-faire persona led Ann Powers to compare her to the screwball comediennes of yore—or draw a connection to Icona Pop and their brazen choruses proclaiming “I don’t care.”3 Cyrus’s performances, though, seem to have pushed buttons in ways that those of her peers haven’t.