Midnight Train to Georgia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yes Catalogue ------1

THE YES CATALOGUE ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 1. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. AUG 1968 2. MAGPIE TV UK ITV 31 DEC 1968 ???? (Rec. 31 Dec 1968) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK M P LTD. JAN 1969 Yes! 56w 4. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 12 JAN 1969 Dear Father (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire Everydays (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Stills Sweetness (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Something's Coming (Rec. 7 Jan 1969) Sondheim/Bernstein 5. TOP GEAR RADIO UK BBC 23 FEB 1969 something's coming (rec. ????) sondheim/bernstein (Peter Banks has this show listed in his notebook.) 6. Marquee Club Programme FLYER UK m p ltd. MAR 1969 (Yes was featured in this edition.) 7. GOLDEN ROSE TV FESTIVAL tv SWITZ montreux 24 apr 1969 - 25 apr 1969 8. radio one club radio uk bbc 22 may 1969 9. THE JOHNNIE WALKER SHOW RADIO UK BBC 14 JUN 1969 Looking Around (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire Sweetness (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Anderson/Squire/Bailey Every Little Thing (Rec. 4 Jun 1969) Lennon/McCartney 10. JAM TV HOLL 27 jun 1969 11. SWEETNESS 7 PS/m/BL & YEL FRAN ATLANTIC 650 171 27 jun 1969 F1 Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 J. Anderson/C. Squire (Bailey not listed) F2 Something's Coming' (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 12. SWEETNESS 7 M/RED UK ATL/POLYDOR 584280 04 JUL 1969 A Sweetness (Edit) 3:43 Anderson/Squire (Bailey not listed) B Something's Coming (From "West Side Story") 7:07 Sondheim/Bernstein 13. -

Booklet-Gobs.Pdf

I like to ute, ute, ute puppurunu Nah,And nah, hope n-n-n-n-nah we’ll meet again(8x) each other. We can create the fun Stomping in the puddles on a 1. Imaginationpuzzu . tomorrow by using our imagnations to move us rainy day “Your attention please. The fun Verse - Make fists and alternate tapping them on Dancing to my favorite song takes the begins now!” Gobs of fun and gobs of goo topWords of each & Music other, then point to your brain, Children'sblues away Vocals Activity Suggestions “This just in. Kids can have fun by simply Words & Music by Stephen Fite Abigail Inyang, Jackie McCarthy Nah, nah, n-n-n-n-nah Here’s the wish I wish for you and then extend one fist and arm into the Makin‚ a milk mustache on my lip using their imaginations.” Additional words to Pepperoni Pizza DJ Argenziano, Addi Berry Nah,This isnah, a variation n-n-n-n-nah on the tune, Apples & That you might rise above the stars air. Encourage the children to join the kids Travelin’ with my family on a great written Stephen Fite Emily Berry, Annabeth Berry Nah,Bananas. nah, n-n-n-n-nahAs a class project, see Nah,And nah, be who n-n-n-n-nah you are (8x) on the CD in asking When, Where, Who, vacation trip Arranged & Produced by Nah,how manynah, nah, other n-n-n-n-nah, foods will work nah with the What & Why. These are just a few of the things I like Verse Nah,melody nah, and n-n-n-n-nah rhythm of this song. -

Artistbio 957.Pdf

An undiscovered island. An epic journey. An illustrious ship. Known just by its name and its logo, GALANTIS could be all or none of these things. A Google search only turns up empty websites and social pages, and mention of a one-off A-Trak collaboration. Is it beats? Art? Something else entirely? At the most basic level, GALANTIS is two friends making music together. The fact that they’re Christian “Bloodshy” Karlsson of Miike Snow and Linus Eklow, aka Style of Eye, is what changes the plot. The accomplished duo’s groundbreaking work as GALANTIS destroys current electronic dance music tropes, demonstrating that emotion and musicianship can indeed coexist with what Eklow calls “a really really big kind of vibe.” “GALANTIS is about challenging, not following.” says Karlsson. Karlsson should know about shaking things up. As half of production duo Bloodshy & Avant, he reinvented pop divas like Madonna, Britney Spears and Kylie Minogue in the early 2000s. He co-wrote and produced Spears’ stunning, career-changing single “Toxic” to the tune of a 2005 Grammy Award for Best Dance Recording. Since then he’s been breaking more ground as one-third of mysterious, jackalobe-branded band Miike Snow. The trio’s two albums, 2009’s self-titled debut and 2011’s Happy To You, fuse the warm pulse of dance music with inspired songcraft, spanning rock, indie, pop and soul. And they recreated that special synthesis live, playing over 300 shows, including big stages like Coachella, Lollapalooza and Ultra Music Festival. As Style of Eye, Eklow has cut his own path through the wilds of electronic music for the last decade, defying genre and releasing work on a diverse swath of labels including of- the-moment EDM purveyors like Fool’s Gold, OWSLA and Refune; and underground stalwarts like Classic, Dirtybird and Pickadoll. -

Vol LI Issue 1

page 2 the paper january 31, 2018 Marc Molinaro, pg. 3 Hygge, pg. 9 Oscars, pg. 15 F & L, pg. 21-22 Earwax, pg. 23 the paper “Favorite U.S. President Based on Looks” c/o Office of Student Involvement Editors-in-Chief Fordham University Colleen “Barack Obama” Burns Bronx, NY 10458 Claire “John Tyler” Nunez [email protected] Executive Editor http://fupaper.blog/ Michael Jack “Lyndon Baines Johnson” O’Brien News Editors the paper is Fordham’s journal of news, analysis, comment and review. Students from all Christian “Theodore Roosevelt” Decker years and disciplines get together biweekly to produce a printed version of the paper using Andrew “Rutherford B. Hayes” Millman Adobe InDesign and publish an online version using Wordpress. Photos are “borrowed” from Opinions Editors Internet sites and edited in Photoshop. Open meetings are held Tuesdays at 9:00 PM in McGin- Jack “Millard Fillmore” Archambault ley 2nd. Articles can be submitted via e-mail to [email protected]. Submissions from Hillary “Franklin Daddy Roosevelt” Bosch students are always considered and usually published. Our staff is more than willing to help new writers develop their own unique voices and figure out how to most effectively convey their Arts Editors thoughts and ideas. We do not assign topics to our writers either. The process is as follows: Meredith “Spiro Agnew” McLaughlin have an idea for an article, send us an e-mail or come to our meetings to pitch your idea, write Annie “Dead White Guy” Muscat the article, work on edits with us, and then get published! We are happy to work with anyone Earwax Editor who is interested, so if you have any questions, comments or concerns please shoot us an e- Marty “Andrew Jackson” Gatto mail or come to our next meeting. -

Quarantine Cabaret Program – Ruth Brown Final

Sheryl McCallum Presents A Tribute to Ruth Brown Featuring Composer David Nehls on Piano Set List MAMA, HE TREATS YOUR DAUGHTER MEAN SENTIMENTAL JOURNEY LUCKY LIPS BE ANYTHING (BUT BE MINE) SO LONG 5-10-15 HOURS IF I CAN’T SELL IT WILD, WILD, YOUNG MEN OH WHAT A DREAM TEARDROPS FROM MY EYES WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD Crew Jonathan Scott-McKean - Technical Director Justin Babcock - Sound Design Liz Scott-McKean - Set Design Vance McKenzie - Lighting Designer Bryanna Scott - Stage Manager Ray Bailey - Video Thank you to our Patrons, Donors, Volunteers, Board of Directors, the Golden Community, the City of Golden, and our Sponsors The Performers Sheryl McCallum was recently seen on the Miners Alley stage as The Principal in our Henry Award Nominated production of Fairfield. Sheryl was recently seen as Melpomene in Xanadu at the Garner Galleria, and as Aunt Eller in Oklahoma! (DCPA). Other roles include Mother in Passing Strange (Aurora Fox Theatre), Delores in Wild Party (DCPA- Off Center); Ruby Baxter in I’ll Be Home For Christmas; Soul Singer in Jesus Christ Superstar, both at Arvada Center and Elegua, in Marcus: Or The Secret Of Sweet at Curious Theatre. Sheryl has performed on Broadway in Disney’s The Lion King, and several City Center Encores! In NYC. Regional roles include: Lady Thiang; The King And I, and Woman #1; The World Goes ‘Round. European Tour: Blackbirds of Broadway. TV: Golden Boy and Order. Sheryl is the creator and host of the MONDAY! MONDAY!- MONDAY! Cabaret The Source Theatre. David Nehls is a composer/lyricist, musical director and actor. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

ALL the TIME in the WORLD a Written Creative Work Submitted to the Faculty of San Francisco State University in Partial Fulfillm

ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD A written creative work submitted to the faculty of San Francisco State University In partial fulfillment of The Requirements for 2 6 The Degree 201C -M333 V • X Master of Fine Arts In Creative Writing by Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California January 2016 Copyright by Jane Marie McDermott 2016 CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL I certify that I have read All the Time in the World by Jane Marie McDermott, and that in my opinion this work meets the criteria for approving a written work submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree: Master of Fine Arts: Creative Writing at San Francisco State University. Chanan Tigay \ Asst. Professor of Creative Writing ALL THE TIME IN THE WORLD. Jane Marie McDermott San Francisco, California 2016 All the Time in the World is the story of gay young people coming to San Francisco in the 1970s and what happens to them in the course of thirty years. Additionally, the novel tells the stories of the people they meet along-the way - a lesbian mother, a World War II veteran, a drag queen - people who never considered that they even had a story to tell until they began to tell it. In the end, All the Time in the World documents a remarkable era in gay history and serves as a testament to the galvanizing effects of love and loss and the enduring power of friendship. I certify that the Annotation is a correct representation of the content of this written creative work. Date ACKNOWLEDGMENT Thanks to everyone in the San Francisco State University MFA Creative Writing Program - you rock! I would particularly like to give shout out to Nona Caspers, Chanan Tigay, Toni Morosovich, Barbara Eastman, and Katherine Kwik. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

046-49 Stonesthrow.Qxd

046 49 StonesThrow.qxd 10/30/06 7:00 AM Page 64 STONES THROW TURNS 10 BY CHRIS MARTINS — PHOTOS BY B+ “I’VE GOT A WHOLE FRIDGE FULL OF WINE,” better known as Egon: general manager, vintage director Jeff Jank, an erstwhile graffiti artist and illus- says Eothen Alapatt with the air of a veteran busi- regional funk archivist, DJ and all-around hustler trator from Oakland who made the move south with nessman. “Going up to places like Lompoc and (though it must be mentioned that he’s much more Wolf. Photographer B+, an Irish transplant whose Buellton right outside Santa Barbara, to these wineries endearing than he is business) for Stones Throw credits include album covers for N.W.A., the Watts that are site specific…it’s just like the music I like.” Records. Of course, this isn’t to say that the label’s Prophets, DJ Shadow, and the majority of the Stones He is, after all, an accomplished record label manager. basic function isn’t happening (that previously men- Throw catalog. Rapper Medaphoar, who grew up with “I feel the same way traveling to Omaha to track a funk tioned “supposed to” about reinventing hip-hop), the label’s flagship artist Madlib in Oxnard, California, band as when I’m going to a winery seeing where they because it most certainly is. But times have changed. 60 miles northwest of L.A. Producer J-Rocc, founding grow the grapes, tasting the wine and meeting the Ten years is a lot of time for an independent hip-hop member of the seminal West Coast turntablist crew people that do it.” But Eothen isn’t an industry old- (etc.) imprint that never had dreams of pressing its the World Famous Beat Junkies (who’ve worked with, timer. -

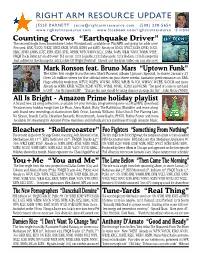

Right Arm Resource Update

RIGHT ARM RESOURCE UPDATE JESSE BARNETT [email protected] (508) 238-5654 www.rightarmresource.com www.facebook.com/rightarmresource 12/10/2014 Counting Crows “Earthquake Driver” The second single from Somewhere Under Wonderland, available on PlayMPE and going for adds now! First week: KINK, WCOO, WEZZ, WEXT, KROK, WVOD, KOHO and KMTN Already on WNCS, WWCT, KCSN, KPND, WJCU, KBAC, KFMU, KMMS, KOZT, KSPN, KTAO, KYSL, WEHM, WFIV, WMWV, KCLC, KNBA, WAPS, WBJB, WMVY, WNRN, WYEP... FMQB Tracks Debut 44* on add week! Still on tour: 12/10 Louisville, 12/12 Indianapolis, 12/13 Madison, 12/16 Davenport IA Just added to the lineup for 2015’s Isle Of Wight Festival! Check out the lyric video on our site now Mark Ronson feat. Bruno Mars “Uptown Funk” The killer first single from the new Mark Ronson album Uptown Special, in stores January 27 Over 20 million views for the official video in just three weeks, fantastic performance on SNL Huge adds this week from WFUV, WXPN, WWNU, WRSI, WBJB, WJCU, WMWV, WCBE, WOCM and more Already on WXRV, KRVB, WZEW, KCMP, WFPK, WYMS, WNKU, KOHO and WCNR “Too good of a tune to just hand to CHR” - Jim McGuinn/KCMP “Stations like ours should be taking chances on songs like this” - John McGue/WNKU All Is Bright - Amazon Prime holiday playlist A brand new 43 song collection, available for your holiday programming now via PlayMPE download Features new holiday songs from Liz Phair, Anna Nalick, Ruby The Rabbitfoot, Blondfire and more along with brand new recordings of classics from Beth Orton, Lucinda Williams, Yoko Ono & The Flaming Lips, No Sinner, Brandi Carlile, Heartless Bastards, Houndmouth, Jessie Baylin, PHOX, Ruthie Foster and more Available for streaming for Amazon Prime members and individual track purchases through Amazon Music Bleachers “Rollercoaster” Foo Fighters “Something From Nothing” The second single from Strange Desire, featuring Jack Antonoff of fun. -

Adjective Adjective Noun Verb Adverb Prepositional Phrase

!"##$%&dd+d)*dr/*&d012)3,*4&*45*)65#5+$78)9::;))r54$d)9:>>?))))))))))))))))))))Volume 1) FRAME SAMPLE (page #) “Here, There” (McCrackens.1980s; M. Brechtel) Salmon Here, Salmon There (54) Colonies Here, Colonies There (54) Pigs Here, Pigs There (54) HERE, THERE (Blank Frame) (54) “Yes, Ma‛am” (Ella Jenkins. Call-Response. 1968) Trophic Levels Yes, Ma‛am (55) Yes, Ma‛am (Blank Frame) (55) Parts of Speech Yes, Ma‛am (56) “I Know A…” I Know A Seahorse (57) I Know An Unusual Ecosystem (57) (Adapted from Peter, Paul & Mary lyrics, 1960‛s) I Know A Meteorologist (57) I Know An Unusual Fish (57) I Know an Unusual Number (57) Marine Cadence (Jodys/ Sound Off. 1944.) California Gold Rush (58) Geography Alive! (59) Starch And Protein Sound-Off (58) American Civilization Cadence (59) Canoe Sound-Off (58) Washington State (60) “Twelve Days of Christmas” (Epiphany: 14-16th C) 12 Days in Gold Rush (61) 12 Days in Medieval Times (61) 12 Days in Arkansas (61) Constitutional Amendments (62-63) “Bugaloo” (Boogaloo. 1966. R.Ray/B.Cruz; A. Brechtel)) Crustacean Bugaloo (64) Egyptian Mummy Bugaloo (65) Aboriginal Life Bugaloo (64) I‛m a Greek God Bugaloo(66) “Johnny Comes Marching Home” (P.S. Gilmore (Civil War), 1863) Solid Shapes Are Everywhere (66) Greeks Go Marching (67) “Nah, Nah, Nah, Nah…” (Steam. 1969.) Scientific Investigation (68) Dolphins In Captivity (69) Others: Pharaoh Song (70) I‛m A Greek 2-3-4 (70) Prepositions (71) Polygon Chant (69) Florist Chant (67) Verbs of Being (71) Plumber Chant (63) Little Insect Egg (71) Ant/ Insect (71) Access the Core-Level 1 Workbook/AMF.2008 (Revised 4-11) 53 HERE, THERE SALMON HERE, SALMON THERE COLONIES HERE, COLONIES THERE PIGS HERE, PIGS THERE By Ana Filipek.