The Pink and Blue Problem: Altercasting in Gendered Advertising

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

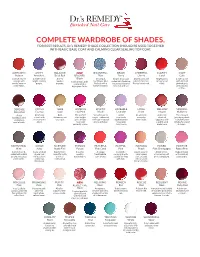

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Pressure Ulcer Staging Cards and Skin Inspection Opportunities.Indd

Pressure Ulcer Staging Pressure Ulcer Staging Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1: Intact skin with non- Stage 1: Intact skin with non- blanchable redness of a localized blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ visible blanching; its color may differ from surrounding area. from surrounding area. Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum- an intact or open/ruptured serum- fi lled blister. fi lled blister. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. -

Pink-To-Red Coral: a Guide to Determining Origin of Color

PINK-TO-RED CORAL: AGUIDE TO DETERMINING ORIGIN OF COLOR Christopher P. Smith, Shane F. McClure, Sally Eaton-Magaña, and David M. Kondo Pink-to-red coral has a long history as an ornamental gem material in jewelry, carvings, and sculptures. However, due to a variety of environmental and legal factors, the supply of high- quality, natural-color coral in this color range has dramatically decreased in recent years— and the quantity of dyed coral on the market has increased. From a study of more than 1,000 natural- and treated-color samples, this article summarizes the procedures that are useful to identify the color origin of pink-to-red coral. A variety of techniques—including magnifica- tion, exposure to acetone, and Raman analysis—can determine if the color of a piece of such coral is dyed. Although there are limitations to the use of magnification and acetone, Raman analysis can establish conclusively that the color is natural. oral is an organic gem material that has been This limitation has led to the practice of dyeing used for ornamental purposes (figure 1) for pale-colored and white coral into the more highly C several thousand years (see, e.g., Walton, valued shades of pink to red. Commonly, the coral 1959). Amulets of red coral dating back to 8000 BC is bleached prior to the dyeing process so that better were uncovered in Neolithic graves in Switzerland, penetration and more homogeneous coloration may coral jewelry was made in Sumeria and Egypt around be achieved (figure 3). Additionally, polymer 3000 BC, and Chinese cultures have valued coral high- impregnation—with or without a coloring agent— ly since about 1000 BC (Liverino, 1989). -

Development and Difference in Germanic Colour Semantics

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264981573 Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics ARTICLE in LANGUAGE SCIENCES · AUGUST 2014 Impact Factor: 0.44 · DOI: 10.1016/j.langsci.2014.07.007 CITATIONS READS 3 87 8 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Cornelia van Scherpenberg Þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Mun… University of Iceland 3 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Linnaea Stockall Matthew Whelpton Queen Mary, University of London University of Iceland 18 PUBLICATIONS 137 CITATIONS 13 PUBLICATIONS 29 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Linnaea Stockall Retrieved on: 03 March 2016 Language Sciences xxx (2014) 1–16 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Language Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/langsci Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics Susanne Vejdemo a,*, Carsten Levisen b, Cornelia van Scherpenberg c, þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck d, Åshild Næss e, Martina Zimmermann f, Linnaea Stockall g, Matthew Whelpton h a Stockholm University, Department of Linguistics, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden b Linguistics and Semiotics, Department of Aesthetics and Communication, Aarhus University, Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2, Bygning 1485-335, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark c Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München, Germany d University of Iceland, Háskóli Íslands, Sæmundargötu 2, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland -

148 Colour Chart

148 colour chart IVORY PRIMROSE BUTTERCUP SOFT LIME TULIP YELLOW LEMON YELLOW CANARY SUNFLOWER ALMOND BLUSH SAFFRON Y418 Y919 Y417 Y828 Y337 Y747 Y657 Y367 Y156 O819 O729 O739 VANILLA PASTEL YELLOW MUSTARD OATMEAL APRICOT HONEYCOMB GOLD AMBER PUMPKIN GINGER BRIGHT ORANGE MANDARIN O929 O949 O948 O628 O538 O547 O555 O567 O467 O136 O177 O277 ORANGE SPICE BURNT ORANGE SATIN DUSKY PINK PUTTY SUNKISSED PINK CORAL SOFT PEACH PEACH MANGO PASTEL PINK R866 O346 R946 Y129 O518 O618 O228 R937 O138 O148 O248 R738 COCKTAIL PINK SALMON PINK ANTIQUE PINK LIPSTICK RED RED BERRY RED RUBY POPPY CRIMSON CARDINAL RED BURGUNDY MAROON R438 R547 R346 R576 R666 R665 R455 R565 R445 R244 R424 M544 PALE PINK BABY PINK ROSE PINK CERISE HOT PINK MAGENTA CARMINE DUSKY ROSE BLOSSOM PINK CARNATION FUCHSIA PINK SLATE R519 R228 M727 M647 R365 M865 R156 R327 M428 M328 M137 V715 AMETHYST PURPLE MULBERRY PLUM AUBERGINE LAVENDER ORCHID LILAC BLUEBELL VIOLET PRUSSIAN BLUE PEARL V626 V546 V865 V735 V524 V518 V528 V327 V127 V245 V464 B528 CORNFLOWER COBALT BLUE CHINA BLUE MIDNIGHT BLUE INDIGO BLUE ROYAL BLUE TRUE BLUE AZURE SKY BLUE CYAN PASTEL BLUE POWDER BLUE B617 B637 B736 B624 V234 V264 B555 B346 B137 C847 C719 B119 ARCTIC BLUE DENIM BLUE AEGEAN FRENCH NAVY COOL AQUA DUCK EGG TURQUOISE MARINE PETROL BLUE HOLLY PINE EMERALD B138 C917 B146 B445 C429 C528 C247 C446 C824 G724 G635 G657 GREEN LUSH GREEN PASTEL GREEN SOFT GREEN MINT GREEN GRASS FOREST GREEN TEA GREEN GREY GREEN MEADOW GREEN APPLE LEAF GREEN G847 G756 G829 G817 G637 G457 G356 G619 G917 G339 G338 G258 BRIGHT GREEN -

Color Chart Colorchart

Color Chart AMERICANA ACRYLICS Snow (Titanium) White White Wash Cool White Warm White Light Buttermilk Buttermilk Oyster Beige Antique White Desert Sand Bleached Sand Eggshell Pink Chiffon Baby Blush Cotton Candy Electric Pink Poodleskirt Pink Baby Pink Petal Pink Bubblegum Pink Carousel Pink Royal Fuchsia Wild Berry Peony Pink Boysenberry Pink Dragon Fruit Joyful Pink Razzle Berry Berry Cobbler French Mauve Vintage Pink Terra Coral Blush Pink Coral Scarlet Watermelon Slice Cadmium Red Red Alert Cinnamon Drop True Red Calico Red Cherry Red Tuscan Red Berry Red Santa Red Brilliant Red Primary Red Country Red Tomato Red Naphthol Red Oxblood Burgundy Wine Heritage Brick Alizarin Crimson Deep Burgundy Napa Red Rookwood Red Antique Maroon Mulberry Cranberry Wine Natural Buff Sugared Peach White Peach Warm Beige Coral Cloud Cactus Flower Melon Coral Blush Bright Salmon Peaches 'n Cream Coral Shell Tangerine Bright Orange Jack-O'-Lantern Orange Spiced Pumpkin Tangelo Orange Orange Flame Canyon Orange Warm Sunset Cadmium Orange Dried Clay Persimmon Burnt Orange Georgia Clay Banana Cream Sand Pineapple Sunny Day Lemon Yellow Summer Squash Bright Yellow Cadmium Yellow Yellow Light Golden Yellow Primary Yellow Saffron Yellow Moon Yellow Marigold Golden Straw Yellow Ochre Camel True Ochre Antique Gold Antique Gold Deep Citron Green Margarita Chartreuse Yellow Olive Green Yellow Green Matcha Green Wasabi Green Celery Shoot Antique Green Light Sage Light Lime Pistachio Mint Irish Moss Sweet Mint Sage Mint Mint Julep Green Jadeite Glass Green Tree Jade -

Chione™ Electric Fuchsia SF90D the Spirit of the ‘80S Is Back in Focus

Pink‘s not dead! Chione™ Electric Fuchsia SF90D The spirit of the ‘80s is back in focus. Break out from rigid societies and reject against mainstream and mass culture. Join the movement that’s all about celebrating fearless individuality, non-conformism and an eco-conscious lifestyle. Stand out with wild textural mixes, shrill neon colors and electrical synth waves. Revive the spirit of pink with a bold make-up statement and strong personality. Pink’s ride on the electric wave: Neon light meets bright colors and beauty enthusiasts of all ages, genders and ethnicities express themselves with unique looks. Bold pink isn’t enough? Show attitude beyond the façade with our vegan pigment that’s good for you — and the environment. Chione™ Electric Fuchsia SF90D An intense magenta metallic-like effect pigment based on synthetic mica that delivers a clean, bold and bright hue using entirely inorganic materials. With an innovative, multi-layer technology, our carmine-free pigment fulfills today’s most requested and desired color need in the market. No staining, bleeding or fading Unique red-blue color space Rich and high chroma with superior coverage and excellent photostability Push it to the limit Chione™ Electric Fuchsia SF90D has no application or color 1 Limelight high coverage lipstick restrictions. Whether used in eyeliner, cream blush, or lip gloss, Fluorescent Coral this pigment covers a unique color palette – from light pink to dark violet. Combine with traditional colorants and effect This high coverage lipstick in a matte finish pigments to elevate your applications. delivers a bold coral color with a flash of unexpected blue to create a fluorescent effect. -

Flags and Symbols � � � Gilbert Baker Designed the Rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’S Gay Freedom Celebration

Flags and Symbols ! ! ! Gilbert Baker designed the rainbow flag for the 1978 San Francisco’s Gay Freedom Celebration. In the original eight-color version, pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for the sun, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for harmony and violet for the soul.! " Rainbow Flag First unveiled on 12/5/98 the bisexual pride flag was designed by Michael Page. This rectangular flag consists of a broad magenta stripe at the top (representing same-gender attraction,) a broad stripe in blue at the bottoms (representing opposite- gender attractions), and a narrower deep lavender " band occupying the central fifth (which represents Bisexual Flag attraction toward both genders). The pansexual pride flag holds the colors pink, yellow and blue. The pink band symbolizes women, the blue men, and the yellow those of a non-binary gender, such as a gender bigender or gender fluid Pansexual Flag In August, 2010, after a process of getting the word out beyond the Asexual Visibility and Education Network (AVEN) and to non-English speaking areas, a flag was chosen following a vote. The black stripe represents asexuality, the grey stripe the grey-are between sexual and asexual, the white " stripe sexuality, and the purple stripe community. Asexual Flag The Transgender Pride flag was designed by Monica Helms. It was first shown at a pride parade in Phoenix, Arizona, USA in 2000. The flag represents the transgender community and consists of five horizontal stripes. Two light blue which is the traditional color for baby boys, two pink " for girls, with a white stripe in the center for those Transgender Flag who are transitioning, who feel they have a neutral gender or no gender, and those who are intersex. -

Pink, Blue and Purple

Pink, Blue and Purple A Lesson Plan from Rights, Respect, Responsibility: A K-12 Curriculum Fostering responsibility by respecting young people’s rights to honest sexuality education. LEARNING OBJECTIVES: NSES ALIGNMENT: By the end of this lesson, students will be able to: GI.2.CC.1 – Define gender, gender identity, and gender-role 1. Define gender, gender identity and gender role stereotypes stereotypes [Knowledge] GI.2.CC.2 – Discuss the range of ways people express their gender 2. Name at least two things they’ve been taught about gender role and how gender-role stereotypes may limit behavior stereotypes, and how those things may limit people of all genders [Knowledge] TARGET GRADE: Grade 1 LESSON RATIONALE: This lesson for lower elementary students provides the foundational TIME: 30 Minutes concept of gender so that students can then understand gender identity and gender role stereotypes. Helping students reflect on things like colors, toys and careers, this lesson teaches students that MATERIALS NEEDED: gender should not be a limiting factor in being who you are and living • Two identical greeting cards authentically. for a new baby, one that is clearly intended for a cisgender ADVANCE PREPARATION: boy, and the other for a cisgender girl • Prepare enough sheets of flipchart paper for half the students in your class. Each sheet should have a large Venn diagram on it. OR The left circle should have the heading, “Girls,” the right circle, • Printout of the gender “Boys,” and the center area “Anyone” stereotype boy and girl greeting cards • Four signs, either printed out or handwritten, with the four GIRLS ANYONE BOYS vocabulary words as indicated in “Advance Preparation” • Sheets of flipchart paper with Venn diagram pre-written on • Purchase two new-baby greeting cards, one of which is very it as described in the Advance Preparation section stereotypically gendered for a boy baby and one for a girl baby. -

COLORS Glitter Sneakers Signature Silk Slip Dress White Button Lipstick Down BRAND GEL POLISH

PARTY READY • HOLIDAY 2021 169 COLORS Glitter Sneakers Signature Silk Slip Dress White Button Lipstick Down BRAND GEL POLISH Cream Puff White Wedding White Button Lady Lilly Studio White Bouquet Naked Naiveté Satin Slippers Mover & Shaker Ice Bar Negligee Down Romantique Pointe Blanc Beau Aurora Winter Glow Unlocked Clearly Pink Uncovered Unmasked Grapefruit Soft Peony Bare Chemise Baby Smile Sparkle Rule Breaker Pink Pursuit Salmon Run Jellied Glitter Sneakers Exquisite Bellini Powder My Nose Wrapped in Sweet Cider Satin Pajamas Flowerbed Folly Chandelier Linen Boheme Iced Cappuccino Clay Canyon Self-Lover Silk Slip Dress Gala Girl Cashmere Wrap Field Fox Nude Knickers Radiant Chill Tundra Fragrant Freesia Candied Be Demure Blushing Topaz Blush Teddy Strawberry Lavender Lace Beckoning Mauve Maverick Coquette Cake Pop Pacifi c Rose Rose Bud Kiss From A Gotcha Smoothie Begonia Rose Holographic Married To The Wooded Bliss Fuji Love Untitled Bronze Sultry Sunset Rooftop Hop Magenta Mischief Tutti Frutti Hot Pop Pink Ecstasy Pink Bikini Museum Meet Mauve Cute Pink Leggings Offbeat Lobster Roll Jelly Bracelet Charm Tropix Beach Escape Sparks Fly Desert Poppy Uninhibited Catch Of The B-Day Candle Mambo Beat Day Soulmate Hollywood Liberté Sangria At Femme Fatale Kiss The Skipper Element Kiss Of Fire Wildfi re Hot Or Knot Soft Flame Devil Red First Love Sunset Hot Chilis Bordeaux Babe Books & Brick Knit Company Red Tartan Punk Rose Brocade Red Baroness Ripe Guava Ruby Ritz Garnet Glamour How Merlot Rouge Rite Beaujolais Rebellious Ruby Decadence -

Color Names Defined by SAS/GRAPH

Appendix C: Color Names Defined by SAS/GRAPH Introduction .............................................................................................. 219 Basic Hues ................................................................................................ 220 Blacks ....................................................................................................... 220 Blues ......................................................................................................... 221 Browns ...................................................................................................... 222 Grays ......................................................................................................... 223 Greens ...................................................................................................... 224 Olives ........................................................................................................ 226 Oranges ..................................................................................................... 226 Pinks ......................................................................................................... 227 Purples ...................................................................................................... 228 Reds .......................................................................................................... 229 Violets ....................................................................................................... 229 Whites ...................................................................................................... -

Heraldic Colors and Meanings

Heraldic Colors THE COLORS ON COATS OF ARMS Color Meaning Image Generosity Or (Gold) Argent (Silver or White) Sincerity, Peace Purpure (Purple) Justice, Sovereignty, Regal Warrior, Martyr, Military Gules (Red) Strength Azure (Blue) Strength, Loyalty Vert (Green) Hope, loyalty in love Sable (Black) Constancy, Grief Tenne or Tawny (Orange) Worthwhile Ambition Sanguine or Murray Victorious, Patient in Battle (Maroon) Red Red is the color of fire and blood, so it is associated with energy, war, danger, strength, power, determination as well as passion, desire, and love. In heraldry, red is used to indicate courage. It is the color found in many national flags. Red brings text and images to the foreground. Red is widely used to indicate danger. This color is also commonly associated with energy, Light red represents joy, passion, sensitivity, and love. Pink signifies romance, love, and friendship. It denotes feminine qualities and passiveness. Dark red is associated with vigor, willpower, rage, anger, leadership, courage, longing, malice, and wrath. Brown suggests stability and denotes masculine qualities. Reddish-brown is associated with harvest and fall. Orange Orange combines the energy of red and the happiness of yellow. It is associated with joy, sunshine, and tropics. Orange represents enthusiasm, fascination, happiness, creativity, determination, attraction, success, encouragement, and stimulation. Orange is associated with healthy food and stimulates appetite. Orange is the color of fall and harvest. In heraldry, orange is symbolic of strength and endurance. Dark orange can mean deceit and distrust. Red-orange corresponds to desire, passion, pleasure, domination, aggression, and thirst for action. Gold evokes the feeling of prestige.