Pink-To-Red Coral: a Guide to Determining Origin of Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Near Vermilion Sands: the Context and Date of Composition of an Abandoned Literary Draft by J. G. Ballard

Near Vermilion Sands: The Context and Date of Composition of an Abandoned Literary Draft by J. G. Ballard Chris Beckett ‘We had entered an inflamed landscape’1 When Raine Channing – ‘sometime international model and epitome of eternal youthfulness’2 – wanders into ‘Topless in Gaza’, a bio-fabric boutique in Vermilion Sands, and remarks that ‘Nothing in Vermilion Sands ever changes’, she is uttering a general truth about the fantastic dystopian world that J. G. Ballard draws and re-draws in his collection of stories set in and around the tired, flamboyant desert resort, a resort where traumas flower and sonic sculptures run to seed.3 ‘It’s a good place to come back to,’4 she casually continues. But, like many of the female protagonists in these stories – each a femme fatale – she is a captive of her past: ‘She had come back to Lagoon West to make a beginning, and instead found that events repeated themselves.’5 Raine has murdered her ‘confidant and impresario, the brilliant couturier and designer of the first bio-fabric fashions, Gavin Kaiser’.6 Kaiser has been killed – with grim, pantomime karma – by a constricting gold lamé shirt of his own design: ‘Justice in a way, the tailor killed by his own cloth.’7 But Kaiser’s death has not resolved her trauma. Raine is a victim herself, a victim of serial plastic surgery, caught as a teenager in Kaiser’s doomed search for perpetual gamin youth: ‘he kept me at fifteen,’ she says, ‘but not because of the fashion-modelling. He wanted me for ever when I first loved him.’8 She hopes to find in Vermilion Sands, in its localized curvature of time and space, the parts of herself she has lost on a succession of operating tables. -

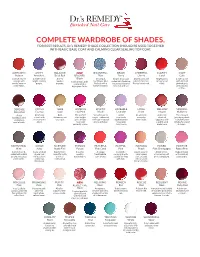

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Annuals for Your Xeriscape

ANNUALS FOR YOUR XERISCAPE Craig R. Miller Parks & Open Space Manager www.cpnmd.org Characteristics of the Best-Drought Tolerant Annuals An annual is a plant that completes its life cycle, from germination to the production of seeds, within one year, and then dies. The best-drought tolerant annuals tend to have smaller leaves, which minimize moisture evaporation. The leaves may be waxy to retain moisture, or they may be covered with silvery or white hairs to reflect light. Drought-tolerant annuals often have long roots so they can reach for moisture deep in the soil. How to Grow Drought-Tolerant Annuals Even drought tolerant plants need a little extra water when they're getting established, so don't just plant and run. Water well while your annuals are settling in, then watch for signs of wilt as the summer progresses. Typically, drought-tolerant annuals require very little care. Most are happy with a deep watering whenever the soil is relatively dry. Most don’t tolerate bone dry soil. Check container plants often! Fertilize regularly throughout the blooming season to support continued flowering. Pinch seedlings at least once or twice to promote bushy growth and deadhead wilted blooms regularly to prevent plants from going to seed early. As a general rule, plants that are suitable for sun or shade are also well suited for containers. Just be sure the plants that share a container have similar needs. Don’t plant sun-loving plants in the same pots as annuals that need shade, or very drought-tolerant annuals with water loving plants. -

Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM) Country Position Paper—Malaysia

CORAL TRIANGLE INITIATIVE: EcOSYSTEM APPROACH TO FISHERIES MANAGEMENT (EAFM) Country Position Paper—Malaysia May 2013 This publication was prepared for Malaysia’s National Coordinating Committee with funding from the United States Agency for International Development’s Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP). Coral Triangle Initiative: Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM): Country Position Paper – Malaysia AUTHOR: Kevin Hiew EDITOR: Jasmin Saad, OceanResearch KEY CONTRIBUTORS: Gopinath Nagarai, Fanli Marine Consultancy USAID PROJecT NUMBER: GCP LWA Award # LAG-A-00-99-00048-00 CITATION: Hiew, K., J. Saad, and N. Gopinath. Coral Triangle Initiative: Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management (EAFM): Country Position Paper—Malaysia. Publication. Honolulu, Hawaii: The USAID Coral Triangle Support Partnership, 2012. Print. PRINTED IN: Honolulu, Hawaii, May 2013 This is a publication of the Coral Triangle Initiative on Corals, Fisheries and Food Security (CTI-CFF). Funding for the preparation of this document was provided by the USAID-funded Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP). CTSP is a consortium led by the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy and Conservation International with funding support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Regional Asia Program. For more information on the Coral Triangle Initiative, please contact: Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries and Food Security Interim-Regional Secretariat Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Mina Bahari Building II, 17th Floor Jalan Medan Merdeka Timur No. 16 Jakarta Pusat 10110, Indonesia www.coraltriangleinitiative.org CTI-CFF National Coordinating Committee Professor Nor Aeni Haji Mokhtar Under Secretary National Oceanography Directorate, Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Level 6, Block C4, Complex C, Federal Government Administrative Centre, 62662 Putrajaya, Malaysia. -

2020 Global Color Trend Report

Global Color Trend Report Lip colors that define 2020 for Millennials and Gen Z by 0. Overview 03 1. Introduction 05 2. Method 06 Content 3. Country Color Analysis for Millennials and Gen Z 3.1 Millennial Lip Color Analysis by Country 08 3.2 Gen Z Lip Color Analysis by Country 09 4. 2020 Lip Color Trend Forecast 4.1 2020 Lip Color Trend Forecast for Millennials 12 4.2 2020 Lip Color Trend Forecast for Gen Z 12 5. Country Texture Analysis for Millennials and Gen Z 5.1 Millennial Lip Texture Analysis by Country 14 5.2 Gen Z Lip Texture Analysis by Country 15 6. Conclusion 17 02 Overview Millennial and Generation Z consumers hold enormous influence and spending power in today's market, and it will only increase in the years to come. Hence, it is crucial for brands to keep up with trends within these cohorts. Industry leading AR makeup app, YouCam Makeup, analyzed big data of 611,382 Millennial and Gen Z users over the course of six months. Based on our findings, we developed a lip color trend forecast for the upcoming year that will allow cosmetics The analysis is based on brands to best tailor their marketing strategy. According to the results, pink will remain the most popular color across all countries and age groups throughout 2020. The cranberry pink shade is the top favorite among Millennials and Gen Z across all countries. Gen Z generally prefers darker 611,382 shades of pink, while millennial consumers lean toward brighter shades. The second favorite shade of pink among Gen Z in Brazil, China, Japan, and the US is Ripe Raspberry. -

Pressure Ulcer Staging Cards and Skin Inspection Opportunities.Indd

Pressure Ulcer Staging Pressure Ulcer Staging Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1: Intact skin with non- Stage 1: Intact skin with non- blanchable redness of a localized blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ visible blanching; its color may differ from surrounding area. from surrounding area. Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum- an intact or open/ruptured serum- fi lled blister. fi lled blister. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. -

UV-LED-OPTIONS-COLOUR-CHART-WEB.Pdf

COLOUR CHART NAILS PERFECTED – Only from Akzentz www.akzentz.com NAILS PERFECTED – Only from Akzentz UV/LED COLOURS P = pearl C = cream F = frost UV/LED ICE I = ice SATIN PEARL (P) BUTTERCUP (C) FIESTA YELLOW (C) SEAFOAM GREEN (C) GREEN SPLASH (C) GLACIER BLUE (C) BLUEBELLE (C) LAVENDER CREAM (C) APRICOT (I) BLUE (I) CHARCOAL (I) PINK (I) GOLD (I) CORAL (I) WHITE (I) VIOLET (I) VIOLET HUE (C) PURPLE LOTUS (C) MAJESTIC VIOLET (C) PINK PEARL (P) PINK INNOCENCE (C) BLISSFUL PINK (C) TENDER PINK (C) LAVENDER PINK (C) TURQUOISE (I) SILK (I) PEWTER (I) MARINE BLUE (I) LIME (I) LATTE (I) UV/LED BRIGHTS B = bright FLAMINGO (C) VIVID PINK (C) SIMPLY PINK (C) TICKLED PINK (C) BRONZE MIST (F) PINK POPPY (C) HIBISCUS PINK (C) MAUVELLA (F) LIME TWIST (B) BLUE ORBIT (B) HYPNOTIC CORAL (B) ORANGE FIX (B) SIZZLING PINK (B) PINK FLIRT (B) YELLOW FLARE (B) CLASSIC RED (C) PINK CHINTZ (C) CHARMING PINK (C) SALMON PINK (C) SOFT CORAL (F) CORAL PINK (C) GLAMOUR PINK (C) CHIFFON (P) UV/LED SPARKLES S = sparkle POWDER PINK (C) PEACH WHISPER (C) SWEET MANDARIN(C) ELECTRIC ORANGE(C) ROSE BISQUE (C) DUSTY ROSE (C) ROSY TAN (C) DREAM PINK (P) STAR DUST (S) CLEAR (S) SUNLIT SNOW (S) SILVER TWINKLE (S) GOLDEN TWILIGHT (S) GOLD (S) BRONZE (S) LILAC (S) CHOCOLAT (C) PRETTY IN PINK (C) CORAL ROSE (C) CHAI (P) TROPICAL SAND (P) PEACHY KEEN (C) MYSTIC MAUVE (F) DESERT ROSE (F) RASPBERRY (S) RAVISHING RED (S) PINK (S) TANGELO (S) CARIBBEAN TEAL (S) BLUE (S) MIDNIGHT DUST (S) UV/LED GEL ART C = cream CHAMPAGNE (P) SIENNA SUNRISE (F) TUSCAN SUNSET (F) BARE (C) VINTAGE BUFF (C) ROSETTE (C) CORAL ESSENCE (C) SHEER MIKAN (C) WHITE (C) CLEAR YELLOW (C) YELLOW (C) GREEN (C) CREAMY GREEN (C) CLEAR BLUE (C) BLUE (C) NAVY BLUE (C) LATTE (C) WILD ROSE (C) WINDSWEPT TAN (C) SMOKEY TAUPE (C) SHADOW GREY (C) PURPLE (C) CREAMY PURPLE (C) RED (C) CHARCOAL (C) BLACK (C) COPYRIGHT © HAIGH INDUSTRIES INC. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

New Record of Melithaea Retifera (Lamarck, 1816) from Andaman and Nicobar Island, India

Indian Journal of Geo Marine Sciences Vol. 48 (10), October 2019, pp. 1516-1520 New record of Melithaea retifera (Lamarck, 1816) from Andaman and Nicobar Island, India J. S. Yogesh Kumar1*, S. Geetha2, C. Raghunathan3 & R. Sornaraj2 1Marine Aquarium and Regional Centre, Zoological Survey of India, (MoEFCC), Government of India, Digha, West Bengal, India. 2Research Department of Zoology, Kamaraj College (Manonmaniam Sundaranar University), Thoothukudi, Tamil Nadu, India. 3Zoological Survey of India (MoEFCC), Government of India, M Block, New Alipore, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. *[E-mail: [email protected]] Received 25 April 2018; revised 04 June 2018 Alcyoniidae octocorals are represented by 405 species in India of which 154 are from Andaman and Nicobar Islands. Surveys conducted in Havelock Island, South Andaman and Shark Island, North Andaman revealed the occurrence of Melithaea retifera and is reported herein as a new distributional record to Andaman and Nicobar Islands. This species is characterised by the clubs of the coenenchyme of the node and internodes and looks like a flower-bud. The structural variations and length of sclerites in the samples are also reported in this manuscript. [Keywords: Octocoral; Soft coral; Melithaeidae; Melithaea retifera; Havelock Island; Shark Island; Andaman and Nicobar; India.] Introduction identification15. The axis of Melithaeidae has short The Alcyonacea are sedentary, colonial growth and long internodes; those sclerites are short, smooth, forms belonging to the subclass Octocorallia. The rod-shaped9. Recently the family Melithaeidae was subclass Octocorallia belongs to Class Anthozoa, recognized18 based on the DNA molecular Phylum Cnidaria and is commonly called as soft phylogenetic relationship and synonymised Acabaria, corals (Alcyonacea), seafans (Gorgonacea), blue Clathraria, Melithaea, Mopsella, Wrightella under corals (Helioporacea), sea pens and sea pencil this family. -

Coral Pink Sand Dunes Data Summary Tables

OFO-BE-07-01 February 2007 A BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF FOREST HEALTH ON MOQUITH MOUNTAIN BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT KANAB AREA FIELD OFFICE By Elizabeth G. Hebertson, Forest Health Protection Specialist S&PF Forest Health Protection, Ogden Field Office Biological Evaluation of Forest Health on Moquith Mountain Abstract In July and October of 2006, the USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Ogden Field Office (FHP-OFO) surveyed approximately 5,000 acres in the Moquith Mountain Wilderness Study Area and Coral Pink Sand Dunes to document current insect and disease activity and to assess stand and landscape level risk. This area was primarily comprised of pinyon-juniper woodlands and stands of ponderosa pine. Individual trees in the Ponderosa Grove Campground and popular dispersed recreation sites were also examined for evidence of insects and diseases and human damage. The results of the survey indicated that endemic levels of insect and disease agents generally occurred within the project area. Juniper gall rust and juniper mistletoe were the most damaging agents detected, although infections caused only minor impacts. No current bark beetle activity was observed. Small patches of ponderosa pine and ponderosa pine stands in the Sand Dune area however, had moderate to high susceptibility to bark beetle infestation. Aspen in the project area exhibited symptoms of decline. A number of insect and disease agents contributed to this damage, but the underlying cause appeared to be stress associated with grazing and plant competition. The trees in recreation sites had injuries typical of those caused by human activity, but this damage had not resulted in tree decline. -

What Is the RED Model of Critical Thinking?

1 What is the RED Model of Critical Thinking? Critical thinking includes many qualities and attributes, including the ability to logically and rationally consider information. Rather than accepting arguments and conclusions presented, a person with strong critical thinking will question and seek to understand the evidence provided. They will look for logical connections between ideas, consider alternative interpretations of information and evaluate the strength of arguments presented. Everyone inherently experiences some degree of subconscious bias in their thinking. Critical thinking skills can help an individual overcome these and separate out facts from opinions. The Watson Glaser critical thinking test is based around the RED model of critical thinking: • Recognize assumptions. This is all about comprehension. Actually understanding what is being stated and considering whether the information presented is true, and whether any evidence has been provided to back it up. Correctly identifying when assumptions have been made is an essential part of this, and being able to critically consider the validity of these assumptions - ideally from a number of different perspectives - can help identify missing information or logical inconsistencies. • Evaluate arguments. This skill is about the systematic analysis of the evidence and arguments provided. Being able to remain objective, while logically working through arguments and information. Critical evaluation of arguments requires an individual to suspend their judgement, which can be challenging when an argument has an emotional impact. It is all too easy to unconsciously seek information which confirms a preferred perspective, rather than critically analyze all of the information. • Draw conclusions. This is the ability to pull together a range of information and arrive at a logical conclusion based on the evidence. -

The Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea 20 Tom C.L

The Great Barrier Reef and Coral Sea 20 Tom C.L. Bridge, Robin J. Beaman, Pim Bongaerts, Paul R. Muir, Merrick Ekins, and Tiffany Sih Abstract agement approaches that explicitly considered latitudinal The Coral Sea lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, bor- and cross-shelf gradients in the environment resulted in dered by Australia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon mesophotic reefs being well-represented in no-take areas in Islands, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, and the Tasman Sea. The the GBR. In contrast, mesophotic reefs in the Coral Sea Great Barrier Reef (GBR) constitutes the western margin currently receive little protection. of the Coral Sea and supports extensive submerged reef systems in mesophotic depths. The majority of research on Keywords the GBR has focused on Scleractinian corals, although Mesophotic coral ecosystems · Coral · Reef other taxa (e.g., fishes) are receiving increasing attention. · Queensland · Australia To date, 192 coral species (44% of the GBR total) are recorded from mesophotic depths, most of which occur shallower than 60 m. East of the Australian continental 20.1 Introduction margin, the Queensland Plateau contains many large, oce- anic reefs. Due to their isolated location, Australia’s Coral The Coral Sea lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, cover- Sea reefs remain poorly studied; however, preliminary ing an area of approximately 4.8 million square kilometers investigations have confirmed the presence of mesophotic between latitudes 8° and 30° S (Fig. 20.1a). The Coral Sea is coral ecosystems, and the clear, oligotrophic waters of the bordered by the Australian continent on the west, Papua New Coral Sea likely support extensive mesophotic reefs.