Near Vermilion Sands: the Context and Date of Composition of an Abandoned Literary Draft by J. G. Ballard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

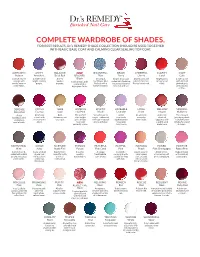

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Download (8Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/110900 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications THE BRITISH LIBRARY BRITISH THESIS SERVICE COPYRIGHT Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. REPRODUCTION QUALITY NOTICE Th e quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction, some pages which contain small or poor printing may not reproduce well. Previously copyrighted material (journal articles, published texts etc.) is not reproduced. THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FLATLINE CONSTRUCTS: GOTHIC MATERIALISM AND CYBERNETIC THEORY-FICTION Mark Fisher Presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Warwick July 1999 Numerous Originals in Colour Abstract FLATLINE CONSTRUCTS: GOTHIC MATERIALISM AND CYBERNETIC THEORY- FICTION Cyberpunk fiction has been called “the supreme literary expression, if not of postmodernism then of late capitalism itself.” (Jameson) This thesis aims to analyse and question this claim by rethinking cyberpunk Action, postmodernism and late capitalism in terms of three - interlocking - themes: cybernetics, the Gothic and fiction. -

UV-LED-OPTIONS-COLOUR-CHART-WEB.Pdf

COLOUR CHART NAILS PERFECTED – Only from Akzentz www.akzentz.com NAILS PERFECTED – Only from Akzentz UV/LED COLOURS P = pearl C = cream F = frost UV/LED ICE I = ice SATIN PEARL (P) BUTTERCUP (C) FIESTA YELLOW (C) SEAFOAM GREEN (C) GREEN SPLASH (C) GLACIER BLUE (C) BLUEBELLE (C) LAVENDER CREAM (C) APRICOT (I) BLUE (I) CHARCOAL (I) PINK (I) GOLD (I) CORAL (I) WHITE (I) VIOLET (I) VIOLET HUE (C) PURPLE LOTUS (C) MAJESTIC VIOLET (C) PINK PEARL (P) PINK INNOCENCE (C) BLISSFUL PINK (C) TENDER PINK (C) LAVENDER PINK (C) TURQUOISE (I) SILK (I) PEWTER (I) MARINE BLUE (I) LIME (I) LATTE (I) UV/LED BRIGHTS B = bright FLAMINGO (C) VIVID PINK (C) SIMPLY PINK (C) TICKLED PINK (C) BRONZE MIST (F) PINK POPPY (C) HIBISCUS PINK (C) MAUVELLA (F) LIME TWIST (B) BLUE ORBIT (B) HYPNOTIC CORAL (B) ORANGE FIX (B) SIZZLING PINK (B) PINK FLIRT (B) YELLOW FLARE (B) CLASSIC RED (C) PINK CHINTZ (C) CHARMING PINK (C) SALMON PINK (C) SOFT CORAL (F) CORAL PINK (C) GLAMOUR PINK (C) CHIFFON (P) UV/LED SPARKLES S = sparkle POWDER PINK (C) PEACH WHISPER (C) SWEET MANDARIN(C) ELECTRIC ORANGE(C) ROSE BISQUE (C) DUSTY ROSE (C) ROSY TAN (C) DREAM PINK (P) STAR DUST (S) CLEAR (S) SUNLIT SNOW (S) SILVER TWINKLE (S) GOLDEN TWILIGHT (S) GOLD (S) BRONZE (S) LILAC (S) CHOCOLAT (C) PRETTY IN PINK (C) CORAL ROSE (C) CHAI (P) TROPICAL SAND (P) PEACHY KEEN (C) MYSTIC MAUVE (F) DESERT ROSE (F) RASPBERRY (S) RAVISHING RED (S) PINK (S) TANGELO (S) CARIBBEAN TEAL (S) BLUE (S) MIDNIGHT DUST (S) UV/LED GEL ART C = cream CHAMPAGNE (P) SIENNA SUNRISE (F) TUSCAN SUNSET (F) BARE (C) VINTAGE BUFF (C) ROSETTE (C) CORAL ESSENCE (C) SHEER MIKAN (C) WHITE (C) CLEAR YELLOW (C) YELLOW (C) GREEN (C) CREAMY GREEN (C) CLEAR BLUE (C) BLUE (C) NAVY BLUE (C) LATTE (C) WILD ROSE (C) WINDSWEPT TAN (C) SMOKEY TAUPE (C) SHADOW GREY (C) PURPLE (C) CREAMY PURPLE (C) RED (C) CHARCOAL (C) BLACK (C) COPYRIGHT © HAIGH INDUSTRIES INC. -

JG Ballard's Reappraisal of Space

Keyes: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space 48 From a ‘metallized Elysium’ to the ‘wave of the future’: J.G. Ballard’s Reappraisal of Space Jarrad Keyes Independent Scholar _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the ‘concrete and steel’ trilogy marks a pivotal moment in Ballard’s intellectual development. From an earlier interest in cities, typically London, Crash ([1973] 1995b), Concrete Island (1974] 1995a) and High-Rise ([1975] 2005) represent a threshold in Ballard’s spatial representations, outlining a critique of London while pointing the way to a suburban reorientation characteristic of his later works. While this process becomes fully realised in later representations of Shepperton in The Unlimited Dream Company ([1979] 1981) and the concept of the ‘virtual city’ (Ballard 2001a), the trilogy makes a number of important preliminary observations. Crash illustrates the roles automobility and containerisation play in spatial change. Meanwhile, the topography of Concrete Island delineates a sense of economic and spatial transformation, illustrating the obsolescence of the age of mechanical reproduction and the urban form of the metropolis. Thereafter, the development project in High-Rise is linked to deindustrialisation and gentrification, while its neurological metaphors are key markers of spatial transformation. The essay concludes by considering how Concrete Island represents a pivotal text, as its location demonstrates. Built in the 1960s, the Westway links the suburban location of Crash to the West with the Central London setting of High-Rise. In other words, Concrete Island moves athwart the new economy associated with Central London and the suburban setting of Shepperton, the ‘wave of the future’ as envisaged in Ballard’s works. -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

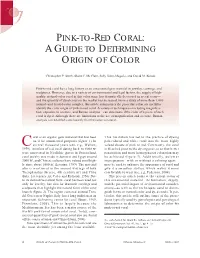

Pink-To-Red Coral: a Guide to Determining Origin of Color

PINK-TO-RED CORAL: AGUIDE TO DETERMINING ORIGIN OF COLOR Christopher P. Smith, Shane F. McClure, Sally Eaton-Magaña, and David M. Kondo Pink-to-red coral has a long history as an ornamental gem material in jewelry, carvings, and sculptures. However, due to a variety of environmental and legal factors, the supply of high- quality, natural-color coral in this color range has dramatically decreased in recent years— and the quantity of dyed coral on the market has increased. From a study of more than 1,000 natural- and treated-color samples, this article summarizes the procedures that are useful to identify the color origin of pink-to-red coral. A variety of techniques—including magnifica- tion, exposure to acetone, and Raman analysis—can determine if the color of a piece of such coral is dyed. Although there are limitations to the use of magnification and acetone, Raman analysis can establish conclusively that the color is natural. oral is an organic gem material that has been This limitation has led to the practice of dyeing used for ornamental purposes (figure 1) for pale-colored and white coral into the more highly C several thousand years (see, e.g., Walton, valued shades of pink to red. Commonly, the coral 1959). Amulets of red coral dating back to 8000 BC is bleached prior to the dyeing process so that better were uncovered in Neolithic graves in Switzerland, penetration and more homogeneous coloration may coral jewelry was made in Sumeria and Egypt around be achieved (figure 3). Additionally, polymer 3000 BC, and Chinese cultures have valued coral high- impregnation—with or without a coloring agent— ly since about 1000 BC (Liverino, 1989). -

And Concrete Island

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by York St John University Institutional Repository York St John University Beaumont, Alexander (2016) Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island. Literary geographies, 2 (1). pp. 96-113. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/2087/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: http://literarygeographies.net/index.php/LitGeogs/article/view/39 Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] Beaumont: Ballard’s Island(s) 96 Ballard’s Island(s): White Heat, National Decline and Technology After Technicity Between ‘The Terminal Beach’ and Concrete Island Alexander Beaumont York St John University _____________________________________ Abstract: This essay argues that the early fiction of J.G. Ballard represents a complex commentary on the evolution of the UK’s technological imaginary which gives the lie to descriptions of the country as an anti-technological society. -

Coral Pink Sand Dunes Data Summary Tables

OFO-BE-07-01 February 2007 A BIOLOGICAL EVALUATION OF FOREST HEALTH ON MOQUITH MOUNTAIN BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT KANAB AREA FIELD OFFICE By Elizabeth G. Hebertson, Forest Health Protection Specialist S&PF Forest Health Protection, Ogden Field Office Biological Evaluation of Forest Health on Moquith Mountain Abstract In July and October of 2006, the USDA Forest Service, Forest Health Protection, Ogden Field Office (FHP-OFO) surveyed approximately 5,000 acres in the Moquith Mountain Wilderness Study Area and Coral Pink Sand Dunes to document current insect and disease activity and to assess stand and landscape level risk. This area was primarily comprised of pinyon-juniper woodlands and stands of ponderosa pine. Individual trees in the Ponderosa Grove Campground and popular dispersed recreation sites were also examined for evidence of insects and diseases and human damage. The results of the survey indicated that endemic levels of insect and disease agents generally occurred within the project area. Juniper gall rust and juniper mistletoe were the most damaging agents detected, although infections caused only minor impacts. No current bark beetle activity was observed. Small patches of ponderosa pine and ponderosa pine stands in the Sand Dune area however, had moderate to high susceptibility to bark beetle infestation. Aspen in the project area exhibited symptoms of decline. A number of insect and disease agents contributed to this damage, but the underlying cause appeared to be stress associated with grazing and plant competition. The trees in recreation sites had injuries typical of those caused by human activity, but this damage had not resulted in tree decline. -

"Resurrected from Its Own Sewers": Waste, Landscape and the Environment in JG Ballard's Climate Novels Set in Junky

"Resurrected from its own sewers": Waste, landscape and the environment in JG Ballard's climate novels Set in junkyards, abandoned waysides and disaster zones, J.G. Ballard’s fiction assumes waste to be integral to the (material and symbolic) post-war landscape, and to reveal discomfiting truths about the ecological and social effects of mass production and consumption. Nowhere perhaps is this more evident than in his so- called climate novels, The Drowned World (1962), The Drought (1965), originally published as The Burning World, and The Crystal World (1966)—texts which Ballard himself described as “form[ing] a trilogy.” 1 In their forensic examination of the ecological effects of the Anthropocene era, these texts at least superficially fulfil the task environmental humanist Kate Rigby sees as paramount for eco-critics and writers of speculative fiction alike: that is, they tell the story of our volatile environment in ways that will productively inform our responses to it, and ultimately enable “new ways of being and dwelling” (147; 3). This article explores Ballard’s treatment of waste and material devastation in The Drowned World, The Drought, and The Crystal World, focussing specifically on their desistance from critiquing industrial modernity, and their exploitation, instead, of the narrative potential of its deleterious effects. I am especially interested in examining the relationship between the three novels, whose strikingly similar storylines approach ecological catastrophe from multiple angles. To this end, I refrain from discussing Ballard’s two other climate novels, The Wind from Nowhere (1962), which he himself dismissed outright as a “piece of hackwork” he wrote in the space of a day, and Hello America (1981), which departs from the 1960s texts in its thematic structure (Sellars and O’Hara, 88). -

The Atrocity Exhibition

The Atrocity Exhibition WITH AUTHOR'S ANNOTATIONS PUBLISHERS/EDITORS V. Vale and Andrea Juno BOOK DESIGN Andrea Juno PRODUCTION & PROOFREADING Elizabeth Amon, Laura Anders, Elizabeth Borowski, Curt Gardner, Mason Jones, Christine Sulewski CONSULTANT: Ken Werner Revised, expanded, annotated, illustrated edition. Copyright © 1990 by J. G. Ballard. Design and introduction copyright © 1990 by Re/Search Publications. Paperback: ISBN 0-940642-18-2 Limited edition of 300 autographed hardbacks: ISBN 0-940642-19-0 BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Consortium, 1045 Westgate Drive, Suite 90, Saint Paul, MN 55114-1065. TOLL FREE: 1-800-283-3572. TEL: 612-221-9035. FAX: 612-221-0124 NON-BOOKSTORE DISTRIBUTION: Last Gasp, 777 Florida Street, San Francisco, CA 94110. TEL: 415-824-6636. FAX: 415-824-1836 U.K. DISTRIBUTION: Airlift, 26 Eden Grove, London N7 8EL TEL: 071-607-5792. FAX: 071-607-6714 LETTERS, ORDERS & CATALOG REQUESTS TO: RE/SEARCH PUBLICATIONS SEND SASE 20ROMOLOST#B FOR SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94133 CATALOG PH (415) 362-1465 FAX (415) 362-0742 REQUESTS Printed in Hong Kong by Colorcraft Ltd. 10987654 Front Cover and all illustrations by Phoebe Gloeckner Back Cover and all photographs by Ana Barrado Endpapers: "Mucous and serous acini, sublingual gland" by Phoebe Gloeckner Phoebe Gloeckner (M.A. Biomedical Communication, Univ. Texas) is an award-winning medical illustrator whose work has been published internationally. She has also won awards for her independent films and comic art, and edited the most recent issue of Wimmin's Comix published by Last Gasp. Currently she resides in the San Francisco Bay Area. Ana Barrado is a photographer whose work has been exhibited in Italy, Mexico City, Japan the United States. -

Contents PROOF

PROOF Contents Acknowledgements vii Notes on Contributors viii Introduction 1 Jeannette Baxter and Rowland Wymer Part I ‘Fictions of Every Kind’: Form and Narrative 1 Ballard’s Story of O: ‘The Voices of Time’ and the Quest for (Non)Identity 19 Rowland Wymer 2 Ballard/Atrocity/Conner/Exhibition/Assemblage 35 Roger Luckhurst 3 Uncanny Forms: Reading Ballard’s ‘Non-Fiction’ 50 Jeannette Baxter Part II ‘The Angle Between Two Walls’: Sex, Geometry and the Body 4 Pornographic Geometries: The Spectacle as Pathology and as Therapy in The Atrocity Exhibition 71 Jen Hui Bon Hoa 5 Disaffection and Abjection in J. G. Ballard’s The Atrocity Exhibition and Crash 88 Emma Whiting 6 Reading Posture and Gesture in Ballard’s Novels 105 Dan O’Hara Part III ‘Babylon Revisited’: Ballard’s Londons 7 The Texture of Modernity in J. G. Ballard’s Crash, Concrete Island and High-Rise 123 Sebastian Groes v September 30, 2011 17:22 MAC/BAXI Page-v 9780230_278127_01_prex PROOF vi Contents 8 J. G. Ballard and William Blake: Historicizing the Reprobate Imagination 142 Alistair Cormack 9 Late Ballard 160 David James Part IV ‘The Personal is Political’: Psychology and Sociopathology 10 Empires of the Mind: Autobiography and Anti-imperialism in the Work of J. G. Ballard 179 David Ian Paddy 11 ‘Going mad is their only way of staying sane’: Norbert Elias and the Civilized Violence of J. G. Ballard 198 J. Carter Wood 12 The Madness of Crowds: Ballard’s Experimental Communities 215 Jake Huntley 13 ‘Zones of Transition’: Micronationalism in the Work of J. G. -

Science Fictional the Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre

Science Fictional The Aesthetics of Science Fiction Beyond the Limits of Genre Andrew Frost University of NSW | College of Fine Arts PhD Media Arts 2013 4 PLEASE TYPE Tl<E UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES Tht:tltiDittorUdon Sht•t Surname or Fenily name: Frost FIRI neme; Andrew OCher namels: Abbr&Yia~lon fof" dcgrco as given in the Unlverslty caltn<S:ar. PhD tCOde: 1289) Sd'IOOI; Seh.ool Of Media Arts Faculty; Coll999 of A ne Am Title: Science Fletfonar.: The AestheUes or SF Beyond the Limit:t of Gcnt'O. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) ScMtnce Flcdonal: The Anthetics of SF Beyond the Umlts of Genre proposes that oonte~my eufture 1$ * $pallal e)Cl>ertence dom1nS'ed by an aesane(IC or science liction and its qua,;.genefic form, the ·$dence ficdonal', The study explores the connective lines between cultural objects suet! as film, video art. painting, illustration, advertising, music, and children's television in a variety ofmediums and media coupled with research that conflates aspects of ctitical theory, art history a nd cuttural studies into a unique d iscourse. The study argues thai three types of C\lltural e ffeets reverberation. densi'ly and resonanoe- affect cultural space altering ood changing the 1ntel'l)totation and influeooe of a cuUural object Through an account of the nature of the science fictional, this thesis argues that science fiction as wo uncJersland It, a.nd how 11 has beon oooventionally concefved, is in fact the counter of its apparent function within wider culture. While terms such as ·genre~ and ·maln-stream• suggest a binary of oentre and periphery, this lh-&&is demonstrates that the quasi-generic is in fact the dominant partner in the process of cultural production, Ocelamlon ,.~ lo disposition or projoct thnlsJdtuen.tlon I htrOby grltlt t<> I~ Ul'll\IOI'IiiY Of Now SOUIJ'I WaltS or i&& agents the rlg:tlllo ard'llve anct to INike available my ttwrsl9 or di$sertabon '" whole or in 1»Jt il'lllle \Jtlivetsay lbrsrles., at IOtmS Of tnedb, rtOW or hero <~~Ot kncwn, 5tAijod:.lo lho Jl«Mdonll ol lho Co9yrlghlt Act 1968.