Development and Difference in Germanic Colour Semantics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

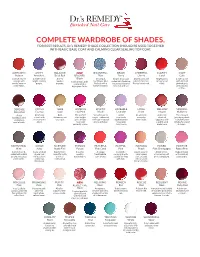

COMPLETE WARDROBE of SHADES. for BEST RESULTS, Dr.’S REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER with BASIC BASE COAT and CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT

COMPLETE WARDROBE OF SHADES. FOR BEST RESULTS, Dr.’s REMEDY SHADE COLLECTION SHOULD BE USED TOGETHER WITH BASIC BASE COAT AND CALMING CLEAR SEALING TOP COAT. ALTRUISTIC AMITY BALANCE NEW BOUNTIFUL BRAVE CHEERFUL CLARITY COZY Auburn Amethyst Brick Red BELOVED Blue Berry Cherry Coral Cafe A playful burnt A moderately A deep Blush A tranquil, Bright, fresh and A bold, juicy and Bright pinky A cafe au lait orange with bright, smokey modern Cool cotton candy cornflower blue undeniably feminine; upbeat shimmer- orangey and with hints of earthy, autumn purple. maroon. crème with a flecked with a the perfect blend of flecked candy red. matte. pinkish grey undertones. high-gloss finish. hint of shimmer. romance and fun. and a splash of lilac. DEFENSE FOCUS GLEE HOPEFUL KINETIC LOVEABLE LOYAL MELLOW MINDFUL Deep Red Fuchsia Gold Hot Pink Khaki Lavender Linen Mauve Mulberry A rich A hot pink Rich, The perfect Versatile warm A lilac An ultimate A delicate This renewed bordeaux with classic with shimmery and ultra bright taupe—enhanced that lends everyday shade of juicy berry shade a luxurious rich, romantic luxurious. pink, almost with cool tinges of sophistication sheer nude. eggplant, with is stylishly tart matte finish. allure. neon and green and gray. to springs a subtle pink yet playful sweet perfectly matte. flirty frocks. undertone. & classic. MOTIVATING NOBLE NURTURE PASSION PEACEFUL PLAYFUL PLEASING POISED POSITIVE Mink Navy Nude Pink Purple Pink Coral Pink Peach Pink Champagne Pastel Pink A muted mink, A sea-at-dusk Barely there A subtle, A poppy, A cheerful A pale, peachy- A high-shine, Baby girl pink spiked with subtle shade that beautiful with sparkly fresh bubble- candy pink with coral creme shimmering soft with swirls of purple and cocoa reflects light a hint of boysenberry. -

Pressure Ulcer Staging Cards and Skin Inspection Opportunities.Indd

Pressure Ulcer Staging Pressure Ulcer Staging Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1: Intact skin with non- Stage 1: Intact skin with non- blanchable redness of a localized blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ visible blanching; its color may differ from surrounding area. from surrounding area. Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum- an intact or open/ruptured serum- fi lled blister. fi lled blister. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. -

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary

ELOISE BUTLER WILDFLOWER GARDEN AND BIRD SANCTUARY WEEKLY GARDEN HIGHLIGHTS Phenology notes for the week of October 5th – 11th It’s been a relatively warm week here in Minneapolis, with daytime highs ranging from the mid-60s the low 80s. It’s been dry too; scant a drop of rain fell over the past week. The comfortable weather was pristine for viewing the Garden’s fantastic fall foliage. Having achieved peak color, the Garden showed shades of amber, auburn, beige, blond, brick, bronze, brown, buff, burgundy, canary, carob, castor, celadon, cherry, cinnabar, claret, clay, copper, coral, cream, crimson, ecru, filemont, fuchsia, gamboge, garnet, gold, greige, khaki, lavender, lilac, lime, magenta, maroon, mauve, meline, ochre, orange, peach, periwinkle, pewter, pink, plum, primrose, puce, purple, red, rose, roseate, rouge, rubious, ruby, ruddy, rufous, russet, rust, saffron, salmon, scarlet, sepia, tangerine, taup, tawny, terra-cotta, titian, umber, violet, yellow, and xanthic, to name a few. According to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the northern two thirds of the state reached peak color earlier in 2020 than it did in both 2019 and 2018, likely due to a relatively cool and dry September. Many garter snakes have been seen slithering through the Garden’s boundless leaf litter. Particularly active this time of year, snakes must carefully prepare for winter. Not only do the serpents need to locate an adequate hibernaculum to pass the winter, but they must also make sure they’ve eaten just the right amount of food. Should they eat too little, they won’t have enough energy to make it through the winter. -

The ISCC-NBS Method of Designating Colors and a Dictionary of Color Names

Uc 8 , .Department of Commerce Na Canal Bureau of Standards Circular UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE • Sinclair Weeks, Secretary NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS • A. V. Astin, Director The ISCC-NBS Method of Designating Colors and a Dictionary of Color Names National Bureau of Standards Circular 553 Issued November 1, 1955 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office, Washington 25, D. C. Price 32 7 1 National Bureau of Standards NOV 1 1955 8 (0*118 QC 00 U555 Cop. 1 Preface I^Ever since the language of man began to develop, words or expressions have been used first to indicate and then to describe colors. Some of these have per- sisted throughout the centuries and are those which refer to the simple colors or ranges such as red or yellow. As the language developed, more and more color names were invented to describe the colors used by art and industry and in late years in the rapidly expanding field of sales promotion. Some of these refer to the pigment or dye used, as Ochre Red or Cochineal, or a geographical location of its source such as Naples Yellow or Byzantium. Later when it became clear that most colors are bought by or for women, many color names indicative of the beauties and wiles of the fan- sex were introduced, as French Nude, Heart’s Desire, Intimate Mood, or Vamp. Fanciful color names came into vogue such as Dream Fluff, Happy Day, Pearly Gates, and Wafted Feather. Do not suppose that these names are without economic importance for a dark reddish gray hat for Milady might be a best seller ; if advertised as Mauve Wine whereas it probably would not if the color were called Paris Mud. -

Color Names Across Languages: Salient Colors and Term Translation in Multilingual Color Naming Models

EUROVIS 2019/ J. Johansson, F. Sadlo, and G. E. Marai Short Paper Color Names Across Languages: Salient Colors and Term Translation in Multilingual Color Naming Models Younghoon Kim, Kyle Thayer, Gabriella Silva Gorsky and Jeffrey Heer University of Washington orange brown red yellow green pink English gray black purple blue 갈 빨강 노랑 주황 연두 자주 초록 회 분홍 Korean 청록 보라 하늘 검정 남 연보라 파랑 Figure 1: Maximum probability maps of English and Korean color terms. Each point represents a 10 × 10 × 10 bin in CIELAB color space. Larger points have a greater likelihood of agreement on a single term. Each bin is colored using the average color of the most probable name term. Bins with insufficient data (< 4 terms) are left blank. English has 10 clusters corresponding to basic English color terms [BK69], whereas Korean exhibits additional clusters for ¨ ( ), ] ( ), 자주 ( ), X늘 ( ), 연P ( ), and 연보| ( ). Abstract Color names facilitate the identification and communication of colors, but may vary across languages. We contribute a set of human color name judgments across 14 common written languages and build probabilistic models that find different sets of nameable (salient) colors across languages. For example, we observe that unlike English and Chinese, Russian and Korean have more than one nameable blue color among fully-saturated RGB colors. In addition, we extend these probabilistic models to translate color terms from one language to another via a shared perceptual color space. We compare Korean-English trans- lations from our model to those from online translation tools and find that our method better preserves perceptual similarity of the colors corresponding to the source and target terms. -

Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Centre for Textile Research Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD 2017 Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker University of Michigan Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons, Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Classical Literature and Philology Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Indo-European Linguistics and Philology Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, and the Other History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Galliker, Julia, "Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204)" (2017). Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD. 27. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/texterm/27 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Centre for Textile Research at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Terminology Associated with Silk in the Middle Byzantine Period (AD 843-1204) Julia Galliker, University of Michigan In Textile Terminologies from the Orient to the Mediterranean and Europe, 1000 BC to 1000 AD, ed. Salvatore Gaspa, Cécile Michel, & Marie-Louise Nosch (Lincoln, NE: Zea Books, 2017), pp. 346-373. -

Pink-To-Red Coral: a Guide to Determining Origin of Color

PINK-TO-RED CORAL: AGUIDE TO DETERMINING ORIGIN OF COLOR Christopher P. Smith, Shane F. McClure, Sally Eaton-Magaña, and David M. Kondo Pink-to-red coral has a long history as an ornamental gem material in jewelry, carvings, and sculptures. However, due to a variety of environmental and legal factors, the supply of high- quality, natural-color coral in this color range has dramatically decreased in recent years— and the quantity of dyed coral on the market has increased. From a study of more than 1,000 natural- and treated-color samples, this article summarizes the procedures that are useful to identify the color origin of pink-to-red coral. A variety of techniques—including magnifica- tion, exposure to acetone, and Raman analysis—can determine if the color of a piece of such coral is dyed. Although there are limitations to the use of magnification and acetone, Raman analysis can establish conclusively that the color is natural. oral is an organic gem material that has been This limitation has led to the practice of dyeing used for ornamental purposes (figure 1) for pale-colored and white coral into the more highly C several thousand years (see, e.g., Walton, valued shades of pink to red. Commonly, the coral 1959). Amulets of red coral dating back to 8000 BC is bleached prior to the dyeing process so that better were uncovered in Neolithic graves in Switzerland, penetration and more homogeneous coloration may coral jewelry was made in Sumeria and Egypt around be achieved (figure 3). Additionally, polymer 3000 BC, and Chinese cultures have valued coral high- impregnation—with or without a coloring agent— ly since about 1000 BC (Liverino, 1989). -

Aspects of St Anna's Cult in Byzantium

ASPECTS OF ST ANNA’S CULT IN BYZANTIUM by EIRINI PANOU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham January 2011 Acknowledgments It is said that a PhD is a lonely work. However, this thesis, like any other one, would not have become reality without the contribution of a number of individuals and institutions. First of all of my academical mother, Leslie Brubaker, whose constant support, guidance and encouragement accompanied me through all the years of research. Of the National Scholarship Foundation of Greece ( I.K.Y.) with its financial help for the greatest part of my postgraduate studies. Of my father George, my mother Angeliki and my bother Nick for their psychological and financial support, and of my friends in Greece (Lily Athanatou, Maria Sourlatzi, Kanela Oikonomaki, Maria Lemoni) for being by my side in all my years of absence. Special thanks should also be addressed to Mary Cunningham for her comments on an early draft of this thesis and for providing me with unpublished material of her work. I would like also to express my gratitude to Marka Tomic Djuric who allowed me to use unpublished photographic material from her doctoral thesis. Special thanks should also be addressed to Kanela Oikonomaki whose expertise in Medieval Greek smoothened the translation of a number of texts, my brother Nick Panou for polishing my English, and to my colleagues (Polyvios Konis, Frouke Schrijver and Vera Andriopoulou) and my friends in Birmingham (especially Jane Myhre Trejo and Ola Pawlik) for the wonderful time we have had all these years. -

148 Colour Chart

148 colour chart IVORY PRIMROSE BUTTERCUP SOFT LIME TULIP YELLOW LEMON YELLOW CANARY SUNFLOWER ALMOND BLUSH SAFFRON Y418 Y919 Y417 Y828 Y337 Y747 Y657 Y367 Y156 O819 O729 O739 VANILLA PASTEL YELLOW MUSTARD OATMEAL APRICOT HONEYCOMB GOLD AMBER PUMPKIN GINGER BRIGHT ORANGE MANDARIN O929 O949 O948 O628 O538 O547 O555 O567 O467 O136 O177 O277 ORANGE SPICE BURNT ORANGE SATIN DUSKY PINK PUTTY SUNKISSED PINK CORAL SOFT PEACH PEACH MANGO PASTEL PINK R866 O346 R946 Y129 O518 O618 O228 R937 O138 O148 O248 R738 COCKTAIL PINK SALMON PINK ANTIQUE PINK LIPSTICK RED RED BERRY RED RUBY POPPY CRIMSON CARDINAL RED BURGUNDY MAROON R438 R547 R346 R576 R666 R665 R455 R565 R445 R244 R424 M544 PALE PINK BABY PINK ROSE PINK CERISE HOT PINK MAGENTA CARMINE DUSKY ROSE BLOSSOM PINK CARNATION FUCHSIA PINK SLATE R519 R228 M727 M647 R365 M865 R156 R327 M428 M328 M137 V715 AMETHYST PURPLE MULBERRY PLUM AUBERGINE LAVENDER ORCHID LILAC BLUEBELL VIOLET PRUSSIAN BLUE PEARL V626 V546 V865 V735 V524 V518 V528 V327 V127 V245 V464 B528 CORNFLOWER COBALT BLUE CHINA BLUE MIDNIGHT BLUE INDIGO BLUE ROYAL BLUE TRUE BLUE AZURE SKY BLUE CYAN PASTEL BLUE POWDER BLUE B617 B637 B736 B624 V234 V264 B555 B346 B137 C847 C719 B119 ARCTIC BLUE DENIM BLUE AEGEAN FRENCH NAVY COOL AQUA DUCK EGG TURQUOISE MARINE PETROL BLUE HOLLY PINE EMERALD B138 C917 B146 B445 C429 C528 C247 C446 C824 G724 G635 G657 GREEN LUSH GREEN PASTEL GREEN SOFT GREEN MINT GREEN GRASS FOREST GREEN TEA GREEN GREY GREEN MEADOW GREEN APPLE LEAF GREEN G847 G756 G829 G817 G637 G457 G356 G619 G917 G339 G338 G258 BRIGHT GREEN -

Berlin and Kay Theory

Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-27851-8_62-2 # Springer Science+Business Media New York 2013 Berlin and Kay Theory C.L. Hardin* Department of Philosophy, Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY, USA Definition The Berlin-Kay theory of basic color terms maintains that the world’s languages share all or part of a common stock of color concepts and that terms for these concepts evolve in a constrained order. Basic Color Terms In 1969 Brent Berlin and Paul Kay advanced a theory of cross-cultural color concepts centered on the notion of a basic color term [1]. A basic color term (BCT) is a color word that is applicable to a wide class of objects (unlike blonde), is monolexemic (unlike light blue), and is reliably used by most native speakers (unlike chartreuse). The languages of modern industrial societies have thousands of color words, but only a very slender stock of basic color terms. English has 11: red, yellow, green, blue, black, white, gray, orange, brown, pink, and purple. Slavic languages have 12, with separate basic terms for light blue and dark blue. In unwritten and tribal languages the number of BCTs can be substantially smaller, perhaps as few as two or three, with denotations that span much larger regions of color space than the BCT denotations of major modern languages. Furthermore, reconstructions of the earlier vocabularies of modern languages show that they gain BCTs over time. These typically begin as terms referring to a narrow range of objects and properties, many of them noncolor properties, such as succulence, and gradually take on a more general and abstract meaning, with a pure color sense. -

Factors Affecting Soil Color, Progress Report No. 2

ACADBIIY OJ' SCIBNCII J'OR IM1 II, FACfORS AFFECTING SOIL COLOR: . PROGRESS REPORT No. 2 .. I. PLICE, OlJalao.... Agrleultual ExperbaeDt Statio., Stillwater In a previous report (PUce 1943) the mechanism of coloration of red. red-and-yellow. gray mineral. and dark organic soUs was dtacusaed. Trull' red colors were described as being due to red·hematite crystals of luftlclent size. translucency. and degree of agglomeration to produce the red color. Since hematite is known to exist In a gamut of colors-from black throuah grays and browns to scarlet and vermiUon-the variety or type that caUla redness in solls must be distinguished from other forms. The lighter red dish and yellowish colors in soUs were explained as being due to leaer degrees of agglomeration and to decreases in crystal size of the hematite. Gray colors were ascribed to a rather short range In the ratio of ferric' to ferrous Iron. The dark colors in so-called "fertile" soils or In soUs in poorly drained depressional areas were found to be due to complex mineral organic pigments. These are of a polyhydroxyphenoUc nature hooked UP with ferric and ferrous Iron; they act not only as acld·base Indicators. but alao as redox Indicators. Subsequent study of soil color phenomena has thrown additional 111ht on the development of grays, browns. and purples, and on their oxygen moisture-base relationships to the metallo-organlc redox pigment colora. In the case of gray colors. where the preponderant color effect Is cauaecl by ferric-ferrous Iron complexes, It Is now found that the Umlts of propor tions of ferric to (errous Iron can evidently be greater than the 8: 2 to J:a ratio previously reported. -

An Appetite for Love and Devotion in Celestial Landscapes - the New York Times

9/10/2019 An Appetite for Love and Devotion in Celestial Landscapes - The New York Times ARCHIVES | 2006 An Appetite for Love and Devotion in Celestial Landscapes By HOLLAND COTTER SEPT. 22, 2006 BOSTON, Sept. 18 - God, love, death and dessert are the menu in "Domains of Wonder: Selected Masterworks of Indian Painting" at the Museum of Fine Arts here, a meal of avid moods and intense sensations. With the first bite your palate is soothed; with the next you break a sweat; by the end you float on a sugar high. Indian artists have spoken of art in gustatory terms for centuries, through an aesthetics based on the concept of "rasa," meaning the emotional taste or savor -- sad, erotic, surly -- evoked by art. If you are evolved enough to discern its presence and qualities, you are called a rasika, a connoisseur, an aesthetic gourmet. And this exhibition of 126 miniature paintings from the Edwin Binney III collection at the San Diego Museum of Art could make instant epicures of us all. As to the order of courses, God is the appetizer, in the form of an early-15th- century Jain devotional mandala done in opaque watercolor on cloth. In effect the image is a flattened aerial map of a highly congested celestial city of apartment blocks and pocket parks, with a Jain savior-deity presiding at its center. A temple floats over his head. Monkeys leap about. And here and there the figures of other green-skinned saviors pop up like olives in a tossed salad. India itself is sometimes envisioned as a spiritual geography, a grand chart of pilgrimage sites and empyreal encampments.