An Appetite for Love and Devotion in Celestial Landscapes - the New York Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eloise Butler Wildflower Garden and Bird Sanctuary

ELOISE BUTLER WILDFLOWER GARDEN AND BIRD SANCTUARY WEEKLY GARDEN HIGHLIGHTS Phenology notes for the week of October 5th – 11th It’s been a relatively warm week here in Minneapolis, with daytime highs ranging from the mid-60s the low 80s. It’s been dry too; scant a drop of rain fell over the past week. The comfortable weather was pristine for viewing the Garden’s fantastic fall foliage. Having achieved peak color, the Garden showed shades of amber, auburn, beige, blond, brick, bronze, brown, buff, burgundy, canary, carob, castor, celadon, cherry, cinnabar, claret, clay, copper, coral, cream, crimson, ecru, filemont, fuchsia, gamboge, garnet, gold, greige, khaki, lavender, lilac, lime, magenta, maroon, mauve, meline, ochre, orange, peach, periwinkle, pewter, pink, plum, primrose, puce, purple, red, rose, roseate, rouge, rubious, ruby, ruddy, rufous, russet, rust, saffron, salmon, scarlet, sepia, tangerine, taup, tawny, terra-cotta, titian, umber, violet, yellow, and xanthic, to name a few. According to the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, the northern two thirds of the state reached peak color earlier in 2020 than it did in both 2019 and 2018, likely due to a relatively cool and dry September. Many garter snakes have been seen slithering through the Garden’s boundless leaf litter. Particularly active this time of year, snakes must carefully prepare for winter. Not only do the serpents need to locate an adequate hibernaculum to pass the winter, but they must also make sure they’ve eaten just the right amount of food. Should they eat too little, they won’t have enough energy to make it through the winter. -

Development and Difference in Germanic Colour Semantics

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264981573 Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics ARTICLE in LANGUAGE SCIENCES · AUGUST 2014 Impact Factor: 0.44 · DOI: 10.1016/j.langsci.2014.07.007 CITATIONS READS 3 87 8 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Cornelia van Scherpenberg Þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Mun… University of Iceland 3 PUBLICATIONS 4 CITATIONS 5 PUBLICATIONS 5 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Linnaea Stockall Matthew Whelpton Queen Mary, University of London University of Iceland 18 PUBLICATIONS 137 CITATIONS 13 PUBLICATIONS 29 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Available from: Linnaea Stockall Retrieved on: 03 March 2016 Language Sciences xxx (2014) 1–16 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Language Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/langsci Two kinds of pink: development and difference in Germanic colour semantics Susanne Vejdemo a,*, Carsten Levisen b, Cornelia van Scherpenberg c, þórhalla Guðmundsdóttir Beck d, Åshild Næss e, Martina Zimmermann f, Linnaea Stockall g, Matthew Whelpton h a Stockholm University, Department of Linguistics, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden b Linguistics and Semiotics, Department of Aesthetics and Communication, Aarhus University, Jens Chr. Skous Vej 2, Bygning 1485-335, 8000 Aarhus C, Denmark c Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Geschwister-Scholl-Platz 1, 80539 München, Germany d University of Iceland, Háskóli Íslands, Sæmundargötu 2, 101 Reykjavík, Iceland -

Factors Affecting Soil Color, Progress Report No. 2

ACADBIIY OJ' SCIBNCII J'OR IM1 II, FACfORS AFFECTING SOIL COLOR: . PROGRESS REPORT No. 2 .. I. PLICE, OlJalao.... Agrleultual ExperbaeDt Statio., Stillwater In a previous report (PUce 1943) the mechanism of coloration of red. red-and-yellow. gray mineral. and dark organic soUs was dtacusaed. Trull' red colors were described as being due to red·hematite crystals of luftlclent size. translucency. and degree of agglomeration to produce the red color. Since hematite is known to exist In a gamut of colors-from black throuah grays and browns to scarlet and vermiUon-the variety or type that caUla redness in solls must be distinguished from other forms. The lighter red dish and yellowish colors in soUs were explained as being due to leaer degrees of agglomeration and to decreases in crystal size of the hematite. Gray colors were ascribed to a rather short range In the ratio of ferric' to ferrous Iron. The dark colors in so-called "fertile" soils or In soUs in poorly drained depressional areas were found to be due to complex mineral organic pigments. These are of a polyhydroxyphenoUc nature hooked UP with ferric and ferrous Iron; they act not only as acld·base Indicators. but alao as redox Indicators. Subsequent study of soil color phenomena has thrown additional 111ht on the development of grays, browns. and purples, and on their oxygen moisture-base relationships to the metallo-organlc redox pigment colora. In the case of gray colors. where the preponderant color effect Is cauaecl by ferric-ferrous Iron complexes, It Is now found that the Umlts of propor tions of ferric to (errous Iron can evidently be greater than the 8: 2 to J:a ratio previously reported. -

Essays on Colour

Essays on Colour ESSAYS ON COLOUR A collection of columns from Cabinet Magazine Eleanor Maclure Introduction For every issue the editors of Cabinet Magazine, an American quarterly arts and culture journal, ask one of their regular contributors to write about a specific colour. The essays are printed as Cabinet’s regular Colours Column. To date, forty-two different colours have been the subject of discussion, beginning with Bice in their first ever issue. I first encountered Cabinet magazine when I stumbled upon Darren Wershler-Henry’s piece about Ruby, on the internet. I have since been able to collect all of the published columns and they have provided a wealth of knowledge, information and invaluable research about colour and colour names. Collectively, the writings represent a varied and engaging body of work, with approaches ranging from the highly factual to the deeply personal. From the birth of his niece in Matthew Klam’s Purple, to a timeline of the history of Lapis Lazuli mining in Ultramarine by Matthew Buckingham, the essays have provided fascinating insights into a whole range of colours, from basic terms such as black and red, to the more obscure: porphyry and puce. While some focus very much on the colour in question, others diverge into intricate tales of history, chemistry or geopolitics. There are personal anecdotes, legends and conspiracies, but more than that, the essays demonstrate the sheer diversity of ways we can talk about colour. The essays gathered here have become far more than just the background reading they began as. The aim of this book is to bring together the works, as a unique representation of the different ways we relate to, experience and interpret colours. -

The Color Red Attracts Attention in an Emotional Context. an ERP Study

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 29 April 2015 doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00212 The color red attracts attention in an emotional context. An ERP study Michał Kuniecki 1*, Joanna Pilarczyk 1 and Szymon Wichary 2 1 Psychophysiology Laboratory, Institute of Psychology, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland, 2 Interdisciplinary Center for Applied Cognitive Studies, University of Social Sciences and Humanities, Warsaw, Poland The color red is known to influence psychological functioning, having both negative (e.g., blood, fire, danger), and positive (e.g., sex, food) connotations. The aim of our study was to assess the attentional capture by red-colored images, and to explore the modulatory role of the emotional valence in this process, as postulated by Elliot and Maier (2012) color-in-context theory. Participants completed a dot-probe task with each cue comprising two images of equal valence and arousal, one containing a prominent red object and the other an object of different coloration. Reaction times were measured, as well as the event-related lateralizations of the EEG. Modulation of the lateralized components revealed that the color red captured and later held the attention in both positive and negative conditions, but not in a neutral condition. An overt motor response to the target stimulus was affected mainly by attention lingering over the visual field where the red cue had been flashed. However, a weak influence of the valence could still be detected in reaction times. Therefore, red seems to guide attention, specifically in emotionally-valenced circumstances, indicating Edited by: that an emotional context can alter color’s impact both on attention and motor John J. -

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\Color{Airforceblueraf}\#5D8aa8

Air Force Blue (Raf) {\color{airforceblueraf}\#5d8aa8} #5d8aa8 Air Force Blue (Usaf) {\color{airforceblueusaf}\#00308f} #00308f Air Superiority Blue {\color{airsuperiorityblue}\#72a0c1} #72a0c1 Alabama Crimson {\color{alabamacrimson}\#a32638} #a32638 Alice Blue {\color{aliceblue}\#f0f8ff} #f0f8ff Alizarin Crimson {\color{alizarincrimson}\#e32636} #e32636 Alloy Orange {\color{alloyorange}\#c46210} #c46210 Almond {\color{almond}\#efdecd} #efdecd Amaranth {\color{amaranth}\#e52b50} #e52b50 Amber {\color{amber}\#ffbf00} #ffbf00 Amber (Sae/Ece) {\color{ambersaeece}\#ff7e00} #ff7e00 American Rose {\color{americanrose}\#ff033e} #ff033e Amethyst {\color{amethyst}\#9966cc} #9966cc Android Green {\color{androidgreen}\#a4c639} #a4c639 Anti-Flash White {\color{antiflashwhite}\#f2f3f4} #f2f3f4 Antique Brass {\color{antiquebrass}\#cd9575} #cd9575 Antique Fuchsia {\color{antiquefuchsia}\#915c83} #915c83 Antique Ruby {\color{antiqueruby}\#841b2d} #841b2d Antique White {\color{antiquewhite}\#faebd7} #faebd7 Ao (English) {\color{aoenglish}\#008000} #008000 Apple Green {\color{applegreen}\#8db600} #8db600 Apricot {\color{apricot}\#fbceb1} #fbceb1 Aqua {\color{aqua}\#00ffff} #00ffff Aquamarine {\color{aquamarine}\#7fffd4} #7fffd4 Army Green {\color{armygreen}\#4b5320} #4b5320 Arsenic {\color{arsenic}\#3b444b} #3b444b Arylide Yellow {\color{arylideyellow}\#e9d66b} #e9d66b Ash Grey {\color{ashgrey}\#b2beb5} #b2beb5 Asparagus {\color{asparagus}\#87a96b} #87a96b Atomic Tangerine {\color{atomictangerine}\#ff9966} #ff9966 Auburn {\color{auburn}\#a52a2a} #a52a2a Aureolin -

4 Colour Words in English and Italian

Connotative meaning in English and Italian Colour-Word Metaphors Gill Philip, Bologna ([email protected]) Abstract Colour words are loaded with attributive, connotative meanings, many of which are realised in conventional linguistic expressions such as to feel blue, to be in the pink, and to see red. The use of such phrases on an everyday basis reinforces the currency of the connotative meanings which they assume in particular cultural and linguistic settings, and the phrases themselves are often cited as evidence of the existence of colours’ connotative meanings. But how do the colour words in conventional linguistic expressions relate to the multitude of symbolic meanings that colours (in general) are said to represent? Based on data extracted from general reference corpora as well as traditional reference works, this article examines the use of colour-word metaphors in English and Italian. It pays particular attention to the ways in which colour words take on connotative meanings, how the meanings are fixed linguistically, and similarities and differences across the two languages under examination. Farbbezeichnungen enthalten viele attributive und konnotative Bedeutungen, wobei viele von ihnen in umgangssprachlichen Ausdrücken vorkommen, wie z.B. to feel blue, to be in the pink und to see red. Die Verwendung derartiger Ausdrücke im alltäglichen Umgang trägt zur weiteren Verbreitung der konnotativen Bedeutungen innerhalb eines bestimmten kulturellen und sprachlichen Umfeldes bei, und die Ausdrücke selber werden oft als Beweis für den offensichtlichen konnotativen Aspekt der Farbbegriffe angeführt. In welchem Verhältnis stehen aber die konventionellen Ausdrücke zur großen Anzahl symbolischer Bedeutungen, die doch Farben (im Allgemeinen) darstellen sollen? Ausgehend von Resultaten allgemeiner reference corpora wie auch herkömmlicher Studien wird hier der Umgang mit Farbbezeichnungsmetaphern (idiomatische Ausdrücke) im Englischen und Italienischen untersucht. -

The Chemistry of Purple Glass

THE CHEMISTRY OF PURPLE GLASS by Rick Baldwin, Brunswick, Ohio As newer collectors become involved in the hobbies of collecting glass bottles and insulators, curiosity develops about how different colors are achieved...particularly with respect to purple and amethyst glass. Questions about purple-colored glass collectibles are routinely posted to social media sites, primarily because of the influx of "irradiated" or "artificially-altered" purple-colored items into these hobbies over the past several decades. New collectors are increasingly wary about purchasing such colored items, especially if there are big prices associated with such, as they do not have the experience in differentiating between "legitimate" and "altered" items. Seasoned collectors can also have significant difficulty, as there are so many variables in the glass-making process that can influence the specific tint, shade, depth-of-color, etc. of the final product, whether color-altered or not. Besides being increasingly available at flea markets and on internet sales and auction sites, color-altered items are routinely observed on sales tables at bottle and insulator shows, despite attempts by show hosts to deter such. As we try to bring new and younger collectors into our "aging" hobbies, it would be self-defeating to turn them away due to their uncertainties in what they may be purchasing for their collection! The following article elucidating the chemistry associated with purple glass was written by the author and previously published in a major insulator hobby periodical. Although this article focuses on glass insulators, the technical content is applicable to any purple and/or "decolorized" bottles, insulators or other early glass collectibles. -

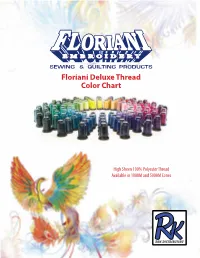

Floriani Thread Color Chart

Floriani Deluxe Thread Color Chart High Sheen 100% Polyester Thread Available in 1000M and 5000M Cones 1 Copper Black Cherry Begonia Light Pink Sangria Deep Violet PF0186 PMS 179C PF0197 PMS 195C PF1083 PMS 191C PF0102 PMS 1895C PF0139 PMS 229C PF0665 PMS 273C 2 Wildflower Old Roseleaf Shrimp Oyster Powder Puff Grape Juice PF0173 PMS 172C PF0196 PMS 506C PF1107 PMS 148C PF0100 PMS Cool Gray 1C PF0133 PMS 514C PF0696 PMS 2685 3 Burnt Orange Cabernet Grapefruit Pale Peach Roseleaf Grape Jam PF0755 PMS 166C PF1586 PMS 1815C PF0155 PMS 1925C PF0110 PMS 503C PF1902 PMS 687C PF0695 PMS 2685C 4 Orange Russet Rose Cerise Rosewater Pink Mist Tulip PF0172 PMS 165C PF0195 PMS 194C PF1082 PMS 190C PF0161 PMS 705C PF0123 PMS 2365C PF0694 PMS 2617C 5 Carrot Cherry Blush Soapstone Wisteria Amethyst PF0537 PMS 151C PF0193 PMS 194C PF0153 PMS 701C PF0163 PMS 488C PF0130 PMS 678C PF0672 PMS 2567C 6 Golden Poppy Scarlet Misty Pink Buff Bright Pink Lavender PF0535 PMS 164C PF0190 PMS 201C PF0117 PMS 701C PF1021 PMS 698C PF0125 PMS 223C PF0673 PMS 2577C 7 Bijol Burgundy Candy Pink Lace Light Lilac Light Mauve PF0526 PMS 1375C PF0194 PMS 202C PF0152 PMS 700C PF0116 PMS 496C PF0131 PMS 236C PF0674 PMS 2587C 8 Sorbet Deep Rust Champagne Light Coral Hot Pink Luxury PF0525 PMS 137C PF0192 PMS 207C PF1011 PMS 706C PF0140 PMS 169C PF0127 PMS 191C PF0675 PMS 526C 9 Apricot Hibiscus Dusty Rose Pink Rose Flamingo Royal Purple PF0533 PMS 137C PF1084 PMS 1925C PF1014 PMS 710C PF1081 PMS 707C PF0128 PMS 240C PF0676 PMS 2617C 10 Pumpkin Persimmon China Rose Pale Pink Deep -

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72

Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Absolute Zero 217° 36% 100% 0 72 186 #0048BA Acid green 65° 43% 76% 176 191 26 #B0BF1A Aero 206° 70% 70% 124 185 232 #7CB9E8 Aero blue 151° 89% 100% 201 255 229 #C9FFE5 African violet 288° 63% 31% 178 132 190 #B284BE Air superiority blue 205° 60% 39% 114 160 193 #72A0C1 Alabaster 46° 90% 27% 237 234 224 #EDEAE0 Alice blue 208° 97% 100% 240 248 255 #F0F8FF Alloy orange 27° 42% 85% 196 98 16 #C46210 Almond 30° 87% 52% 239 222 205 #EFDECD Amaranth 348° 53% 78% 229 43 80 #E52B50 Amaranth (M&P) 328° 40% 57% 159 43 104 #9F2B68 Amaranth pink 338° 78% 75% 241 156 187 #F19CBB Amaranth purple 342° 41% 63% 171 39 79 #AB274F Amaranth red 356° 48% 73% 211 33 45 #D3212D Amazon 147° 35% 35% 59 122 87 #3B7A57 Amber 45° 50% 100% 255 191 0 #FFBF00 Amber (SAE/ECE) 30° 50% 100% 255 126 0 #FF7E00 Amethyst 270° 60% 50% 153 102 204 #9966CC Android green 74° 50% 55% 164 198 57 #A4C639 Antique brass 22° 63% 47% 205 149 117 #CD9575 Antique bronze 52° 26% 55% 102 93 30 #665D1E Antique fuchsia 316° 46% 22% 145 92 131 #915C83 Antique ruby 350° 31% 66% 132 27 45 #841B2D Antique white 34° 91% 78% 250 235 215 #FAEBD7 Ao (English) 120° 25% 100% 0 128 0 #008000 Apple green 74° 36% 100% 141 182 0 #8DB600 Apricot 24° 84% 90% 251 206 177 #FBCEB1 Aqua 180° 50% 100% 0 255 255 #00FFFF Aquamarine 160° 75% 100% 127 255 212 #7FFFD4 Swatch Name HLS RGB HEX Arctic lime 72° 54% 100% 208 255 20 #D0FF14 Army green 69° 23% 44% 75 83 32 #4B5320 Artichoke 76° 53% 13% 143 151 121 #8F9779 Arylide yellow 51° 67% 74% 233 214 107 #E9D66B Ash gray 135° 72% 8% 178 190 -

The Sarah Belk Gambrell Collection of European Porcelain

THE SARAH BELK GAMBRELL COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PORCELAIN Thursday, June 24, 2021 DOYLE.COM THE SARAH BELK GAMBRELL COLLECTION OF EUROPEAN PORCELAIN AUCTION Thursday, June 24, 2021 at 10am Eastern EXHIBITION Friday, June 18, Noon – 5pm Saturday, June 19, Noon – 5pm Sunday, June 20, Noon – 5pm Monday, June 21, 10am – 6pm And by Appointment at other times Safety protocols will be in place with limited capacity. Please maintain social distance during your visit. LOCATION Doyle Auctioneers & Appraisers 175 East 87th Street New York, NY 10128 212-427-2730 This Gallery Guide was created on (date) Please see addendum for any changes The most up to date information is available On DOYLE.COM Sale Info View Lots and Place Bids Doyle New York 1 2 Elizabeth I Silver-Mounted Rhenish Böttger Red Stoneware Coffee Pot and Cover Saltglazed 'Tigerware' Jug Circa 1710-15, designed by J.J. Irminger Circa 1580, the silver mount inscribed on the Of squared pear form, the conforming domed hinge 'PETER ELY, OBT. 1684', on the cover cover with pagoda knop, the scroll handle with 'GEO. GUNNING 1815 WATERLOO' and on the channeled sides and a studded exterior, the underside of the foot 'GIVEN BY KING squared curved spout issuing from the gaping CHARLES THE SECOND' and 'G.G. TO M.G. jaws of a scaly serpent, a double-scroll bridge 1834' support above, each side of the body lightly Globular with cylindrical neck and loop handle polished, on a flaring stepped square foot. mottled in brown, the repoussé cover caste with Height 7 3/4 inches, width 6 1/2 inches. -

Graphics = Light = Color = Memory

Graphics = Light = Color = Memory • Light-emitting media CRT: cathode ray tube — phosphors excited by electrons LCD: liquid crystal display — liquid crystals in a grid; current controls polarization and thus controls what colors can be seen Projected LCD: LCD image is magnified before it reaches the viewer Plasma: noble gas in between two glass sheets, also affiliated with an electrode grid; current excites the gas to emit light • Light-emitting media use an additive approach to color: add a color by adding light in that color (i.e., white = light in all colors) • Light-reflecting media (print) Ink-jet: fine spray of pigment onto display medium (most of the time, paper) Thermal transfer: heat changes pigment on special paper Laser: laser beam “etches” image on a drum coated with toner • Light-reflecting media use a subtractive approach to color: pigments absorb unwanted colors until only the desired color reflects back (i.e., white = no pigment) Vector Displays • Line-based: Electron gun traces lines directly from point A to point B • Based on oscilloscope technology — so pretty much restricted to CRT technology • Made a lot of sense back when memory was expensive… … but what does memory have to do with graphics anyway? Raster Displays • Grid-based: Display is a two-dimensional raster (array) of individual picture elements (pixels) in memory This memory block goes by many names: frame buffer, graphics memory, VRAM • Display devices transfer or map this 2D grid onto their specific type of display • CRT: electron gun scans the entire screen horizontally