11. Fatimah Chuchu & Najib Noorashid.Cdr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating the Field: Fieldwork Strategies in Observation in Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia*

Navigating the Field: Fieldwork Strategies in Observation in Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia* Azizi Fakhri and Farah Purwaningrum Abstract The paper examines the kinds of fieldwork strategies in observation that can be mobilised to reduce time and secure access to the field, yet at the same time keeping depth and breadth in ethnographic research. Observation, as a research method, has been one of the ‘core techniques’ profoundly used by sociologists particularly in ‘focused ethnography’ (Knoblauch, 2005). The ‘inside-outside’ (Merton 1972, as cited in Laberee, 2002: 100) and ‘emic-ethic’ dichotomies have always been associated with observation. However, issues like ‘cultural disparity’ (Ezeh, 2003), ‘accessibility’ (Brown-Saracino, 2014); ‘dual-identity’ (Watts, 2011) and ‘local languages’ (Shtaltova and Purwaningrum, 2016) would have limited one’s observation in his/her fieldwork. To date, literature on the issue of time-restriction is under- researched. Thus, the focus of this paper is two-fold; first, it examines how observation and its related fieldwork strategies were used in fieldworks conducted by the authors in two Southeast Asian countries: Tutong, Brunei Darussalam in 2014-2015 and Bekasi, Indonesia in 2010-2011. The paper also examines how observation can be utilised to gain an in-depth understanding in an emic research. Based on our study, we contend that observation holds key importance in an ethnographic research. Although a researcher has an emic standpoint, due to his or her ethnicity or nationality, accessibility is not automatic. As a method, observation needs to be used altogether with other methods, such as audio-visual, drawing being made by respondents, pictures or visuals. -

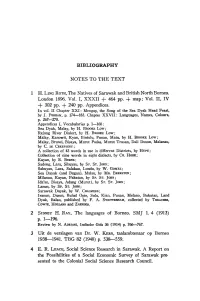

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

PMW Tutong District

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for December, 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Bukit Udal, Mukim Tanjong Maya 1 Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Bukit Udal Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 2 Kampong Long Mayan, Mukim Ukong Tutong Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Long Mayan Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar, Mukim Tanjong Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Penapar, Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar and 3 Maya Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm surrounding area. Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau, Pertanian Birau Office and surrounding 4 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm area. Monday Perumahan Baitul Mal Keriam, Mukim Keriam A whole of Perumahan Baitul Mal, a part of Kampong Keriam and 5 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. 3rd Dec 2018 Tutong. surrounding area. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Serambangun, Mukim Tanjong Maya A whole Spg 333-37-39-16 Kampong Serambangun and 6 Wayleave Clearing 4th Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong. surrounding areas. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau and Pertanian Birau Office and 7 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. -

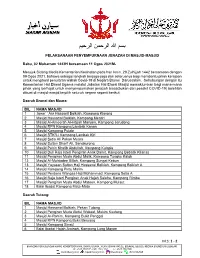

Perlaksanaan Pengurusan Jenazah Di

مﺳﺑ ﷲ نﻣﺣرﻟا مﯾﺣرﻟا PELAKSANAAN PENYEMPURNAAN JENAZAH DI MASJID-MASJID Rabu, 02 Muharram 1443H bersamaan 11 Ogos 2021M- Merujuk Sidang Media Kementerian Kesihatan pada hari Isnin, 29 Zulhijjah 1442 bersamaan dengan 09 Ogos 2021, bahawa sebagai langkah berjaga-jaga dan seterusnya bagi membantu pihak kerajaan untuk mengawal penularan wabak Covid-19 di Negara Brunei Darussalam. Sehubungan dengan itu Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama melalui Jabatan Hal Ehwal Masjid memaklumkan bagi mana-mana pihak yang berhajat untuk menyempurnakan jenazah biasa(bukan dari pesakit COVID-19) bolehlah dibuat di masjid-masjid terpilih seluruh negara seperti berikut; Daerah Brunei dan Muara: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Jame’ ‘ Asr Hassanil Bolkiah, Kampong Kiarong 2 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Mentiri 3 Masjid Al-Ameerah Al-Hajjah Maryam, Kampong Jerudong 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Lambak Kanan 5 Masjid Kampong Pulaie 6 Masjid STKRJ Kampong Lambak Kiri 7 Masjid Setia Ali Pekan Muara 8 Masjid Sultan Sharif Ali, Sengkurong 9 Masjid Pehin Khatib Abdullah, Kampong Kulapis 10 Masjid Duli Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Damit, Kampong Bebatik Kilanas 11 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Malik, Kampong Tungku Katok 12 Masjid Al-Muhtadee Billah, Kampong Sungai Kebun 13 Masjid Yayasan Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Bolkiah A 14 Masjid Kampong Pintu Malim 15 Masjid Perdana Wangsa Haji Mohammad, Kampong Setia A 16 Masjid Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajah Saleha, Kampong Rimba 17 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Mateen, Kampong Mulaut 18 Balai Ibadat Kampong Mata-Mata Daerah Tutong: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Pekan Tutong 2 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Wakeel, Mukim Kiudang 3 Masjid Ar-Rahim, Kampong Bukit Penggal 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Bukit Beruang 5 Masjid Kampong Sinaut 6 Balai Ibadat Hajah Aminah, Kampong Long Mayan M.S: 1 - 2 _ BAHAGIAN PERHUBUNGAN AWAM, KEMENTERIAN HAL EHWAL UGAMA, JALAN DEWAN MAJLIS, BERAKAS, BB3910, NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM. -

8/14/2010 Pelitabrunei Nama-Nama Amil Keluaran 14 Ogos Pelita1

2 HARI SABTU 14 OGOS 2010 ZAKAT FITRAH BAGI TAHUN 1431H BERSAMAAN 2010M SENARAI NAMA-NAMA AMIL BAGI SELURUH NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BAGI TAHUN 1431-1432H / 2010-2011M BIL KAWASAN NAMA AMIL TEMPAT MEMBAYAR KERAMAIAN AMIL-AMIL DAN KAWASAN-KAWASAN BAGI SELURUH 31. Jalan Tasek Lama hingga NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM BAGI TAHUN 1431 - 1432H / 2010 - 2011M Terrace Hotel 32. Jalan Stoney Yang Mulia, Mudim Awang KERAMAIAN AMIL 33. Jalan Dato Ibrahim Haji Amran bin Haji Mohd. JABATAN / DAERAH KAWASAN 34. Jalan Istana Darussalam Salleh JABATAN MAJLIS UGAMA ISLAM 29 ORANG 4 35. Kg. Pengiran Pemanca Lama 36. Kg. Sungai Kedayan A dan B Masjid Omar 163 ORANG BRUNEI / MUARA 75 37. Kg. Kianggeh dan Sekitarnya 'Ali Saifuddien BELAIT 27 ORANG 15 38. Kg. Ujong Tanjong 39. Kg. Kuala Sg. Peminyak Yang Mulia, Mudim Awang TUTONG 55 ORANG 30 40. Kg. Ujong Bukit Haji Ahmad Kasra bin Haji 41. Kg. Limbongan Ibrahim TEMBURONG 17 ORANG 12 42. Kg. Bukit Salat JUMLAH 291 ORANG 136 43. Kg. Sumbiling Lama Yang Mulia Ustaz Haji Adanan Surau Ibu Pejabat SENARAI NAMA-NAMA AMIL JABATAN MAJLIS UGAMA ISLAM Balai Bomba Bandar Seri Begawan bin Haji Ahmad Perkhidmatan Bomba 2. Brunei (Khas untuk Pegawai dan (Ketua Guru Agama Jabatan dan Penyelamat, BAGI TAHUN 1431-1432H / 2010-2011M Kakitangan serta keluarganya) Perkhidmatan Bomba dan Lapangan Terbang Penyelamat) Lama Berakas, Brunei BIL LANTIKAN ATAS NAMA JAWATAN BIL LANTIKAN ATAS NAMA BATANG TUBUH 2. BANDAR SERI BEGAWAN 'B' mengandungi: BIL KAWASAN NAMA AMIL TEMPAT MEMBAYAR 1. Setiausaha Majlis Ugama Islam, Brunei 1. Awang Haji Abd. Wahab bin Haji Sapar (Awang Haji Harun bin Haji Junid) (Pegawai Ugama Kanan Kumpulan 2) Awang Haji Ahmad bin Haji 2. -

Membaca Masa Silam Kadazandusun Berasaskan Mitos Dan Legenda

.,. MEMBACA MASA SILAM KADAZANDUSUN BERASASKAN MITOS DAN LEGENDA Oleh: . LOW KOK ON Tesis diserahkan untuk memenuhi keperluan bagi , Ijazah Doktor Falsafah November 2003 PENGHARGAAN Penulis ingin mengambil kesempatan ini merakamkan setinggi-tinggi terima kasih kepada Profesor Madya Dr. Noriah Taslim, Penyelia Utama, dan Dr. Jelani Harun, Penyelia Kedua penulis. Tanpa titik peluh, bimbingan dan galakan daripada mereka yang tidak terhingga buat selama beberapa tahun, tesis ini tidak mungkin terbentuk ---. sebagaimana yang ada pada sekarang. Penulis juga ingin merakamkan ribuan terima kasih kepada semua pemberi maklumat, yang tersenarai di Lampiran 1 dan Lampiran 2, pihak Perpustakaan Universiti ------· ·~ 5ain~ Malaysia, Perpustakaan Universiti Malaysia Sa bah, Perpustakaan Penyelidikan Tun Fuad Stephen (Sabah), Perpustakaan Muzium Negeri Sabah dan Arkib Negeri Sabah kerana telah memberikan bantuan dari segi pembekalan maklumat untuk membolehkan penyelidikan ini dilaksanakan. Penulis turut terhutang budi ~epada beberapa individu dan rakan karib seperti Profesor Dr. Ahmat Adam, Dr. Jason Lim Miin Hwa, Ismail Ibrahim, Saidatul Nornis, Asmiaty Amat, Veronica Petrus Atin, Benedict Topin, Rita Lasimbang, Misterin Radin, Mary Ellen Gidah, Pamela Petrus, Ooi Beng Keong, Ch'ng Kim San, Ong Giak Siang, Samsurina Mohamad Sham, Geoffrey Tanakinjal dan beberapa orang individu lain yang telah memberikan sokongan moral dan bantuan kepada penulis. 11 Kepada isteri tersayang Goh Moi Hui, dan anak-anak yang dikasihi, iaitu Low Wei Shang dan Low Wei Ying, kalianlah yang menjadi ubat penawar dan pemberi semangat, tatkala penulis sedang bergelut dengan ombak besar dan terpijak ranjau dalam proses menyiapkan tesis ini. Tanpa pengorbanan kalian sedemikian rupa, penghasilan tesis ini pasti tidak akan menjadi kenyataan. LOW KOK ON UNIVERSffi SAINS MALAYSIA PULAU PINANG 18 NOVEMBER 2003 iii _KANDUNGAN PENGHARGAAN ........................... -

PMW Tutong District (Press Release) Memo25

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for October and November , 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Kampong Lubuk Ubar, Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 1 Jln Kuru-Benutan, Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Lubuk Ubar and surrounding area. 16th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.00 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong Tuesday Kampong Sebakit Atas, Mukim Tanjong Maya 2 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. Spg 49 Kampong Sebakit Atas and surrounding area. 16th Oct 2018 tutong Wednesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 3 Wayleave Clearing 17th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong area. Wednesday Kampong Sulap Samat, Jalan Panchong, Mukim A part of Kampong Sulap Samat, Jln Panchong and surrounding 4 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. 17th Oct 2018 Lamunin area. Thursday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 5 Wayleave Clearing 18th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Mukim Rambai, Tutong area. Thursday 6 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Kampong Penabai, Mukim Pekan Tutong Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. A part of Kampong Penabai and surrounding area. 18th Oct 2018 Kampong Benutan and Kampong kerancing, Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Benutan,Kampong kerancing and surrounding 7 Mukim Rambai, Tutong Wayleave Clearing 20th Oct 2018 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm area. -

PMW Tutong District

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for October , 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Maintenance works for low voltage overhead 1 08th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kampong Padnunuk, Mukim Kiudang, Tutong lines. A part of Jln Kecil Padnunuk , Jln Andaru and surrounding area. Monday Hospital Pengiran Muda Mahkota Pengiran Muda Maintenance works for Distribution 2 08th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah, Tutong Transformer#3. A part of Hospital Building and the surrrounding area. Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 3 08th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kg Ukong, Mukim Ukong Wayleave Clearing for overhead lines A part of Kg Ukong and the surrrounding area. Tuesday Maintenance works for Distribution 4 09th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Earth Satellite, Telisai, Tutong. Transformer#1. Earth satellite Building and the surrounding area. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Maintenance works for low voltage overhead 5 09th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kampong Padnunuk, Mukim Kiudang, Tutong, lines. Jln Andaru, a part of Jln Kecil Padnunuk and surrounding areas. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 6 09th Oct 2018 2.00pm to 4.30 pm Kg Ukong, Mukim Ukong Wayleave Clearing for overhead lines A part of Kg Ukong and the surrrounding area. Wednesday Maintenance works for Distribution 7 10th Oct 2018 8.30 am to 04.30 pm Earth Satellite, Telisai, Tutong. -

Uhm Ma 3222 R.Pdf

Ui\i1VEi~.'3!TY OF HA\/VAI'I LIBRARY PLANNING KADAZANDUSUN (SABAH, MALAYSIA): LABELS, IDENTITY, AND LANGUAGE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LINGUISTICS MAY 2005 By Trixie M. Tangit Thesis Committee: AndrewD. W. Wong, Chairperson Kenneth L. Rehg Michael L. Fonnan © 2005, Trixie M. Tangit 111 For the Kadazandusun community in Sabah, Malaysia and for the beloved mother tongue IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to take this opportunity to record my gratitude and heartfelt thanks to all those who have helped. me to accomplish my study goals throughout the M.A. program. Firstly, my thanks and appreciation to the participants who have contributed to this study on the Kadazandusun language: In particular, I thank Dr. Benedict Topin (from the Kadazan Dusun Cultural Association (KDCA», Ms. Evelyn Annol (from the Jabatan Pendidikan Negeri Sabab/ Sabah state education department (JPNS», and Ms. Rita Lasimbang (from the Kadazandusun Language Foundation (KLF». I also take this opportunity to thank Mr. Joe Kinajil, ex-JPNS coordinator (retired) ofthe Kadazandusun language program in schools, for sharing his experiences in the early planning days ofthe Kadazandusun language and for checking language data. I also wish to record my sincere thanks to Ms. Pamela Petrus Purser and Mr. Wendell Gingging for their kind assistance in checking the language data in this thesis. Next, my sincere thanks and appreciation to the academic community at the Department ofLinguistics, University ofHawai'i at Manoa: In particular, mahalo nui loa to my thesis committee for their feedback, support, and advice. -

Persidangan Dewan Majlis

PAGI HARI KHAMIS, 2 RABIULAKHIR 1431 / 18 MAC 2010 206 DEWAN MAJLIS Khamis, 2 Rabiulakhir 1431 / 18 Mac 2010 YANG DI-PERTUA Duli Yang Teramat Mulia DAN AHLI-AHLI MAJLIS Paduka Seri Pengiran Muda Mahkota MESYUARAT NEGARA Pengiran Muda Haji Al-Muhtadee Billah ibni Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri HADIR: Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah, DKMB., DPKT., YANG DI-PERTUA: King Abdul Aziz Ribbon, First Class (Saudi Arabia), The Order of the Renaissance (First Yang Amat Mulia Degree) (Jordan), Medal of Honour (Lao), Pengiran Indera Mahkota Pengiran Anak DSO (Singapore), Order of Lakandula with (Dr.) Kemaludin Al-Haj ibni Al-Marhum the Rank of Grand Cross (Philippines), DSO Pengiran Bendahara Pengiran Anak Haji (Military) (Singapore), PHBS., Mohd. Yassin, PSLJ., SPMB., POAS., Menteri Kanan di Jabatan Perdana Menteri, PHBS., PBLI., PJK., PKL., Negara Brunei Darussalam. Yang Di-Pertua , Negara Brunei Darussalam. Duli Yang Teramat Mulia Paduka Seri Pengiran Perdana Wazir AHLI-AHLI RASMI KERANA JAWATAN Sahibul Himmah Wal-Waqar Pengiran (PERDANA MENTERI DAN MENTERI- Muda Mohamed Bolkiah ibni Al-Marhum MENTERI): Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien, DKMB., DK., PHBS., PBLI., Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia PJK., Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Menteri Hal Ehwal Luar Negeri dan Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Perdagangan, Negara Brunei Darussalam. Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien, Sultan dan Yang Yang Berhormat Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam, Pehin Orang Kaya Seri Lela Dato Seri Setia Perdana Menteri, Menteri Pertahanan dan Haji Awang Abdul Rahman bin Dato Setia Menteri Kewangan, Negara Brunei Haji Mohamed Taib, PSNB., SLJ., PHBS., Darussalam. -

Buku Poskod Edisi Ke 2 (Kemaskini 26122018).Pdf

Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pada bahgian hadapan sampul surat:- RAJAH PERTAMA PENGGUNAAN MUKA HADAPAN SAMPUL SURAT 74 MM 40 MM Ruangan untuk kegunaan pengirim Ruangan untuk alamat penerima Ruangan 20 MM untuk kegunaan Pejabat Pos 20 MM 140 MM Lebar Panjang Ukuran minimum 90 mm 140 mm Ukuran maksimum 144 mm 264 mm Bagi surat yang dikirim melalui pos, alamat pengirim hendaklah ditulis pada bahagian penutup belakang sampul surat. Ini membolehkan surat berkenaan dapat dikembalikan kepada pengirim sekiranya surat tersebut tidak dapat diserahkan kepada si penerima seperti yang dikehendaki. Disamping itu. ianya juga menolong penerima mengenal pasti alamat dan poskod awda yang betul. Dengan cara ini penerima akan dapat membalas surat awda dengan alamat dan poskod yang betul. Berikut adalah contoh menulis alamat pengirim pada bahagian penutup sampul surat:- RAJAH DUA Jabatan Perkhidmatan Pos berhasrat memberi perkhidmatan yang efesien kepada awda. Oleh itu, kerjasama awda sangat-sangat diperlukan. Adalah menjadi tugas awda mempastikan ketepatan maklumat-maklumat alamat dan poskod awda kerana ianya merupakan kunci bagi kecepatan penyerahan surat awda GARIS PANDU SKIM POSKOD NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM Y Z 0 0 0 0 Kod Daerah Kod Mukim Kod Kampong / Kod Pejabat Kawasan Penyerahan Contoh: Y Menunjukan Kod Daerah Z Menunjukan Kod Mukim 00 Menunjukan Kod Kampong/Kawasan 00 Menunjukan Kod Pejabat Penyerahan KOD DAERAH BIL Daerah KOD 1. Daerah Brunei Muara B 2. Daerah Belait K 3. Daerah Tutong T 4. Daerah Temburong P POSKOD BAGI KEMENTERIAN- KEMENTERIAN -

Learning Kadazan for Kids

UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI PETRONAS (UTP) Learning Kadazan For Kids by LORENZO HARDY HADYMOND 12636 Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Technology (Hons) (Information & Communication Technology) DECEMBER 2012 UniversitiTeknologi PETRONAS Bandar Seri Iskandar, 31750 Tronoh Perak Darul Ridzuan CERTIFICATION OF APPROVAL Learning Kadazan For Kids By Lorenzo Hardy Hadymond A project dissertation submitted to the Information Technology Programme Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the BACHELOR OF TECHNOLOGY (Hons) (INFORMATION & COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGY) Approved by, _________________________________________ (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dayang Rohaya Bt. Awang Rambli) UNIVERSITI TEKNOLOGI PETRONAS TRONOH, PERAK December 2012 ii December 2012 CERTIFICATION OF ORIGINALITY This is to certify that I am responsible for the work submitted in this project, that the original work is my own except as specified in the reference and acknowledgements, and that the original work contained herein has not been undertaken or done by unspecified sources or persons. _______________________________ (LORENZO HARDY HADYMOND) iii ABSTRACT Learning Kadazan for Children is a mobile application on Android smart phones that is aimed as an alternative to books as learning tools where children can widen their vocabularies and improve their spellings on Kadazan words. This is an effort to counter the declining rate of this language usage in Sabah especially of the Kadazan- borned children. The development platform of this application is the Android operating system. The target users are the children of the Kadazan community from the age of seven to twelve years old. Parents who own Android smart phone may assist their children in using the application and in learning as well.