The Case of Dusun in Brunei Darussalam

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Navigating the Field: Fieldwork Strategies in Observation in Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia*

Navigating the Field: Fieldwork Strategies in Observation in Brunei Darussalam and Indonesia* Azizi Fakhri and Farah Purwaningrum Abstract The paper examines the kinds of fieldwork strategies in observation that can be mobilised to reduce time and secure access to the field, yet at the same time keeping depth and breadth in ethnographic research. Observation, as a research method, has been one of the ‘core techniques’ profoundly used by sociologists particularly in ‘focused ethnography’ (Knoblauch, 2005). The ‘inside-outside’ (Merton 1972, as cited in Laberee, 2002: 100) and ‘emic-ethic’ dichotomies have always been associated with observation. However, issues like ‘cultural disparity’ (Ezeh, 2003), ‘accessibility’ (Brown-Saracino, 2014); ‘dual-identity’ (Watts, 2011) and ‘local languages’ (Shtaltova and Purwaningrum, 2016) would have limited one’s observation in his/her fieldwork. To date, literature on the issue of time-restriction is under- researched. Thus, the focus of this paper is two-fold; first, it examines how observation and its related fieldwork strategies were used in fieldworks conducted by the authors in two Southeast Asian countries: Tutong, Brunei Darussalam in 2014-2015 and Bekasi, Indonesia in 2010-2011. The paper also examines how observation can be utilised to gain an in-depth understanding in an emic research. Based on our study, we contend that observation holds key importance in an ethnographic research. Although a researcher has an emic standpoint, due to his or her ethnicity or nationality, accessibility is not automatic. As a method, observation needs to be used altogether with other methods, such as audio-visual, drawing being made by respondents, pictures or visuals. -

Belait District

BELAIT DISTRICT His Majesty Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam ..................................................................................... Kebawah Duli Yang Maha Mulia Paduka Seri Baginda Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah Mu’izzaddin Waddaulah ibni Al-Marhum Sultan Haji Omar ‘Ali Saifuddien Sa’adul Khairi Waddien Sultan dan Yang Di-Pertuan Negara Brunei Darussalam BELAIT DISTRICT Published by English News Division Information Department Prime Minister’s Office Brunei Darussalam BB3510 The contents, generally, are based on information available in Brunei Darussalam Newsletter and Brunei Today First Edition 1988 Second Edition 2011 Editoriol Advisory Board/Sidang Redaksi Dr. Haji Muhammad Hadi bin Muhammad Melayong (hadi.melayong@ information.gov.bn) Hajah Noorashidah binti Haji Aliomar ([email protected]) Editor/Penyunting Sastra Sarini Haji Julaini ([email protected]) Sub Editor/Penolong Penyunting Hajah Noorhijrah Haji Idris (noorhijrah.idris @information.gov.bn) Text & Translation/Teks & Terjemahan Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan ([email protected]) Layout/Reka Letak Hajah Apsah Haji Sahdan Proof reader/Penyemak Hajah Norpisah Md. Salleh ([email protected]) Map of Brunei/Peta Brunei Haji Roslan bin Haji Md. Daud ([email protected]) Photos/Foto Photography & Audio Visual Division of Information Department / Bahagian Fotografi -

Preliminary Report of BPP 2011

! ! ! Kerajaan!Kebawah!Duli!Yang!Maha!Mulia!Paduka!Seri!Baginda!Sultan!dan!Yang!Di8Pertuan! Negara! Brunei! Darussalam! melalui! Jabatan! Perancangan! dan! Kemajuan! Ekonomi! (JPKE),! Jabatan!Perdana!Menteri,!telah!mengendalikan!Banci!Penduduk!dan!Perumahan!(BPP)!pada! tahun! 2011.! BPP! 2011! merupakan! banci! kelima! seumpamanya! dikendalikan! di! negara! ini.! Banci!terdahulu!telah!dijalankan!pada!tahun!1971,!1981,!1991!dan!2001.! ! Laporan! Awal! Banci! Penduduk! dan! Perumahan! 2011! ini! merupakan! penerbitan! pertama! dalam! siri! laporan8laporan! banci! yang! akan! dikeluarkan! secara! berperingkat8peringkat.! Laporan! ini! memberikan! data! awal! mengenai! jumlah! penduduk,! isi! rumah! dan! tempat! kediaman!serta!taburan!dan!pertumbuhan!mengikut!daerah.!! ! Saya! berharap! penerbitan! ini! dan! laporan8laporan! seterusnya! akan! dapat! memenuhi! keperluan! pelbagai! pengguna! di! negara! ini! bagi! maksud! perancangan,! penyelidikan,! penyediaan!dasar!dan!sebagai!bahan!rujukan!awam.! ! Saya! sukacita! merakamkan! setinggi8tinggi! penghargaan! dan! terima! kasih! kepada! Penerusi! dan! ahli8ahli! Komiti! Penyelarasan! Kebangsaan! BPP! 2011,! kementerian8kementerian,! jabatan8jabatan! dan! sektor! swasta! yang! telah! memberikan! bantuan! dan! kerjasama! yang! diperlukan! kepada! Jabatan! ini! semasa! banci! dijalankan.! Seterusnya! saya! juga! sukacita! mengucapkan! terima! kasih! kepada! rakyat! dan! penduduk! di! negara! ini! di! atas! kerjasama! dalam! memberikan! maklumat! yang! dikehendaki! kepada! pegawai8pegawai! banci! -

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs

CHAPTER 6 English for the Indigenous People of Sarawak: Focus on the Bidayuhs Patricia Nora Riget and Xiaomei Wang Introduction Sarawak covers a vast land area of 124,450 km2 and is the largest state in Malaysia. Despite its size, its population of 2.4 million people constitutes less than one tenth of the country’s population of 30 million people (as of 2015). In terms of its ethnic composition, besides the Malays and Chinese, there are at least 10 main indigenous groups living within the state’s border, namely the Iban, Bidayuh, Melanau, Bisaya, Kelabit, Lun Bawang, Penan, Kayan, Kenyah and Kajang, the last three being collectively known as the Orang Ulu (lit. ‘upriver people’), a term that also includes other smaller groups (Hood, 2006). The Bidayuh (formerly known as the Land Dayaks) population is 198,473 (State Planning Unit, 2010), which constitutes roughly 8% of the total popula- tion of Sarawak. The Bidayuhs form the fourth largest ethnic group after the Ibans, the Chinese and the Malays. In terms of their distribution and density, the Bidayuhs are mostly found living in the Lundu, Bau and Kuching districts (Kuching Division) and in the Serian district (Samarahan Division), situated at the western end of Sarawak (Rensch et al., 2006). However, due to the lack of employment opportunities in their native districts, many Bidayuhs, especially youths, have migrated to other parts of the state, such as Miri in the east, for job opportunities and many have moved to parts of Peninsula Malaysia, espe- cially Kuala Lumpur, to seek greener pastures. Traditionally, the Bidayuhs lived in longhouses along the hills and were involved primarily in hill paddy planting. -

PMW Tutong District

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for December, 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Bukit Udal, Mukim Tanjong Maya 1 Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Bukit Udal Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong Saturday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon 2 Kampong Long Mayan, Mukim Ukong Tutong Wayleave Clearing A part of Kampong Long Mayan Tutong and surrounding areas. 1st Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar, Mukim Tanjong Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Penapar, Jalan Sekolah Rendah Penapar and 3 Maya Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm surrounding area. Monday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau, Pertanian Birau Office and surrounding 4 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. Wayleave Clearing 3rd Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm area. Monday Perumahan Baitul Mal Keriam, Mukim Keriam A whole of Perumahan Baitul Mal, a part of Kampong Keriam and 5 8.00 am to 4.30 pm Maintenance works for Distribution Transformer. 3rd Dec 2018 Tutong. surrounding area. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon Kampong Serambangun, Mukim Tanjong Maya A whole Spg 333-37-39-16 Kampong Serambangun and 6 Wayleave Clearing 4th Dec 2018 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Tutong. surrounding areas. Tuesday 8.00 am to 12.00 noon A part of Kampong Birau and Pertanian Birau Office and 7 Pertanian Birau, Mukim Kiudang Tutong. -

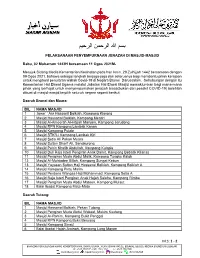

Perlaksanaan Pengurusan Jenazah Di

مﺳﺑ ﷲ نﻣﺣرﻟا مﯾﺣرﻟا PELAKSANAAN PENYEMPURNAAN JENAZAH DI MASJID-MASJID Rabu, 02 Muharram 1443H bersamaan 11 Ogos 2021M- Merujuk Sidang Media Kementerian Kesihatan pada hari Isnin, 29 Zulhijjah 1442 bersamaan dengan 09 Ogos 2021, bahawa sebagai langkah berjaga-jaga dan seterusnya bagi membantu pihak kerajaan untuk mengawal penularan wabak Covid-19 di Negara Brunei Darussalam. Sehubungan dengan itu Kementerian Hal Ehwal Ugama melalui Jabatan Hal Ehwal Masjid memaklumkan bagi mana-mana pihak yang berhajat untuk menyempurnakan jenazah biasa(bukan dari pesakit COVID-19) bolehlah dibuat di masjid-masjid terpilih seluruh negara seperti berikut; Daerah Brunei dan Muara: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Jame’ ‘ Asr Hassanil Bolkiah, Kampong Kiarong 2 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Mentiri 3 Masjid Al-Ameerah Al-Hajjah Maryam, Kampong Jerudong 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Lambak Kanan 5 Masjid Kampong Pulaie 6 Masjid STKRJ Kampong Lambak Kiri 7 Masjid Setia Ali Pekan Muara 8 Masjid Sultan Sharif Ali, Sengkurong 9 Masjid Pehin Khatib Abdullah, Kampong Kulapis 10 Masjid Duli Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Damit, Kampong Bebatik Kilanas 11 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Malik, Kampong Tungku Katok 12 Masjid Al-Muhtadee Billah, Kampong Sungai Kebun 13 Masjid Yayasan Sultan Haji Hassanal Bolkiah, Kampong Bolkiah A 14 Masjid Kampong Pintu Malim 15 Masjid Perdana Wangsa Haji Mohammad, Kampong Setia A 16 Masjid Raja Isteri Pengiran Anak Hajah Saleha, Kampong Rimba 17 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Mateen, Kampong Mulaut 18 Balai Ibadat Kampong Mata-Mata Daerah Tutong: BIL NAMA MASJID 1 Masjid Hassanal Bolkiah, Pekan Tutong 2 Masjid Pengiran Muda Abdul Wakeel, Mukim Kiudang 3 Masjid Ar-Rahim, Kampong Bukit Penggal 4 Masjid RPN Kampong Bukit Beruang 5 Masjid Kampong Sinaut 6 Balai Ibadat Hajah Aminah, Kampong Long Mayan M.S: 1 - 2 _ BAHAGIAN PERHUBUNGAN AWAM, KEMENTERIAN HAL EHWAL UGAMA, JALAN DEWAN MAJLIS, BERAKAS, BB3910, NEGARA BRUNEI DARUSSALAM. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Copy of PMW Tutong District (Press Release) 1Wk July18

English Section Listed below are the designated areas for the planned maintenance work as for July, 2018: No. Day & Date Time Location Work Description Affected Areas for Outages 08.30 am to 11.30 am Tuesday Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, 1 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Extension of 11kV network Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, Tutong 03rd July 2018 Tutong 08.30 am to 11.30 am Wednesday Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, 2 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Extension of 11kV network Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, Tutong 04th July 2018 Tutong 08.30 am to 11.30 am Thursday Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, 3 1.30 pm to 4.30 pm Extension of 11kV network Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, Tutong 05th July 2018 Tutong 08.30 am to 11.30 am Friday Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, 4 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Extension of 11kV network Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, Tutong 06th July 2018 Tutong Satuday 08.30 am to 11.30 am kampong Rambai and Kampong Kuala Maintenance works for Low voltage overhead A part of Kampong Rambai and 5 07th July 2018 Ungar, Mukim Rambai, Tutong lines Kampong Kuala Ungar, Tutong. 08.30 am to 11.30 am Satuday Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, 6 2.00 pm to 4.30 pm Extension of 11kV network Kampong Sulap Samat, Mukim Lamunin, Tutong 07th July 2018 Tutong Monday 08.30 am to 11.30 am Kampong Padnunok, Mukim Kiudang, Maintenance works for Low voltage overhead 7 A part of Kampong Padnunok, Tutong. -

Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M

Philippine Institute for Development Studies Surian sa mga Pag-aaral Pangkaunlaran ng Pilipinas Inequality of Opportunities Among Ethnic Groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES NO. 2017-42 The PIDS Discussion Paper Series constitutes studies that are preliminary and subject to further revisions. They are being circulated in a limited number of copies only for purposes of soliciting comments and suggestions for further refinements. The studies under the Series are unedited and unreviewed. The views and opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute. Not for quotation without permission from the author(s) and the Institute. December 2017 For comments, suggestions or further inquiries please contact: The Research Information Department, Philippine Institute for Development Studies 18th Floor, Three Cyberpod Centris – North Tower, EDSA corner Quezon Avenue, 1100 Quezon City, Philippines Tel Nos: (63-2) 3721291 and 3721292; E-mail: [email protected] Or visit our website at https://www.pids.gov.ph Inequality of opportunities among ethnic groups in the Philippines Celia M. Reyes, Christian D. Mina and Ronina D. Asis. Abstract This paper contributes to the scant body of literature on inequalities among and within ethnic groups in the Philippines by examining both the vertical and horizontal measures in terms of opportunities in accessing basic services such as education, electricity, safe water, and sanitation. The study also provides a glimpse of the patterns of inequality in Mindanao. The results show that there are significant inequalities in opportunities in accessing basic services within and among ethnic groups in the Philippines. -

Prayer Cards | Joshua Project

Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Abkhaz in Ukraine Abor in India Population: 1,500 Population: 1,700 World Popl: 307,600 World Popl: 1,700 Total Countries: 6 Total Countries: 1 People Cluster: Caucasus People Cluster: South Asia Tribal - other Main Language: Abkhaz Main Language: Adi Main Religion: Non-Religious Main Religion: Unknown Status: Minimally Reached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: Unknown % Chr Adherents: 20.00% Chr Adherents: 16.36% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: Complete Bible www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Apsuwara - Wikimedia "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Achuar Jivaro in Ecuador Achuar Jivaro in Peru Population: 7,200 Population: 400 World Popl: 7,600 World Popl: 7,600 Total Countries: 2 Total Countries: 2 People Cluster: South American Indigenous People Cluster: South American Indigenous Main Language: Achuar-Shiwiar Main Language: Achuar-Shiwiar Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Main Religion: Ethnic Religions Status: Minimally Reached Status: Minimally Reached Evangelicals: 1.00% Evangelicals: 2.00% Chr Adherents: 14.00% Chr Adherents: 15.00% Scripture: New Testament Scripture: New Testament www.joshuaproject.net www.joshuaproject.net Source: Gina De Leon Source: Gina De Leon "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 "Declare his glory among the nations." Psalm 96:3 Pray for the Nations Pray for the Nations Adi in India Adi Gallong in India -

Freedom of Religion and Belief in the Southeast Asia

FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND BELIEF IN THE SOUTHEAST ASIA: LEGAL FRAMEWORK, PRACTICES AND INTERNATIONAL CONCERN FREEDOM OF RELIGION AND BELIEF IN THE SOUTHEAST ASIA: LEGAL FRAMEWORK, PRACTICES AND INTERNATIONAL CONCERN Alamsyah Djafar Herlambang Perdana Wiratman Muhammad Hafiz Published by Human Rights Working Group (HRWG): Indonesia’s NGO Coalition for International Human Rights Advocacy 2012 1 Freedom of Religion and Belief in the Southeast Asia: ResearchLegal Framework, team Practices and International Concern : Alamsyah Djafar Herlambang Perdana Wiratman EditorMuhammad Hafiz Expert: readerMuhammad Hafiz : Ahmad Suaedy SupervisorYuyun Wahyuningrum : Rafendi Djamin FirstMuhammad edition Choirul Anam : Desember 2012 Published by: Human Rights Working Group (HRWG): Indonesia’s NGO Coalition for International Human Rights Advocacy Jiwasraya Building Lobby Floor Jl. R.P. Soeroso No. 41 Gondangdia, Jakarta Pusat, Indonesia Website: www.hrwg.org / email: [email protected] ISBN 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD INTRODUCTION BY EDITOR Chapter I Diversities in Southeast Asia and Religious Freedom A. Preface ChapterB.IIHumanASEAN Rights and and Guarantee Freedom for of ReligionFreedom of Religion A. ASEAN B. ASEAN Inter-governmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR) C. Constitutionalism, Constitutions and Religious Freedom ChapterD.IIIInternationalThe Portrait Human of Freedom Rights Instruments of Religion in in ASEAN Southeast StatesAsia A. Brunei Darussalam B. Indonesia C. Cambodia D. Lao PDR E. Malaysia F. Myanmar G. Philippines H. Singapore I. Thailand ChapterJ. IVVietnamThe Attention of the United Nations Concerning Religious Freedom in ASEAN: Review of Charter and Treaty Bodies A. Brunei Darussalam B. Indonesia C. Cambodia D. Lao PDR E. Malaysia F. Myanmar G. Philippines H. Singapore I. Thailand J. Vietnam 3 Chapter IV The Crucial Points of the Guarantee of Freedom of Religion in Southeast Asia A.