Mission to Care for the Sick EN

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

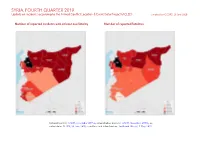

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

Allocation Strategy Syria Humanitarian Fund 2019 1St Standard Allocation

Allocation Strategy Syria Humanitarian Fund 2019 1st Standard Allocation I. Allocation Overview Project Proposal Deadline: 15 September 2019 23:59, Damascus Time A) Introduction / Humanitarian situation 1. The Syria Humanitarian Fund (SHF) is a Country-Based Pooled Fund (CBPF) managed by the Humanitarian Financing Unit (HFU) of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) based in Damascus. Established in 2014, under the leadership of the Humanitarian Coordinator a.i. for Syria, its role is to support life-saving, protection, and life-sustaining activities by filling critical funding gaps; promote the needs-based delivery of assistance in accordance with humanitarian principles; improve the relevance and coherence of humanitarian response by strategically funding priorities as identified in the HRP; and expand the rapid delivery of assistance to underserved, high severity and hard-to-reach areas by partnering with the best placed actors.1 2. On 20 June, the SHF Advisory Board agreed to allocate US $25 million under the First Standard Allocation to support life-saving activities and service delivery in underserved areas of southern Syria – specifically, Dar’a, Quneitra and Rural Damascus (with a focus on eastern Ghouta) – where severe humanitarian needs persist. The decision came following a detailed prioritization exercise undertaken by the Inter Sector Coordination (ISC) group in Syria which involved a multi-factor analysis of levels of need (with an emphasis on highest severity need areas); accessibility (both in terms of newly-accessible and access-restricted locations); population movement (focusing on those locations where there is a high concentration of both IDPs and returnees); presence and functionality of basic services (including health and education facilities), and coverage (in terms of people reached). -

RSCAS 2019/06 from Rebel Rule to a Post-Capitulation Era in Daraa

RSCAS 2019/06 Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Middle East Directions Programme Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria From Rebel Rule to a Post-Capitulation Era in Daraa Southern Syria: The Impacts and Outcomes of Rebel Behaviour During Negotiations Abdullah Al-Jabassini European University Institute Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Middle East Directions Programm Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria From Rebel Rule to a Post-Capitulation Era in Daraa Southern Syria: The Impacts and Outcomes of Rebel Behaviour During Negotiations Abdullah Al-Jabassini From Rebel Rule to a Post-Capitulation Era in Daraa Southern Syria: The Impacts and Outcomes of Rebel Behaviour During Negotiations EUI Working Paper RSCAS 2019/06 This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper, or other series, the year and the publisher. ISSN 1028-3625 © Abdullah Al-Jabassini, 2019 Printed in Italy, January 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies The Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, created in 1992 and currently directed by Professor Brigid Laffan, aims to develop inter-disciplinary and comparative research on the major issues facing the process of European integration, European societies and Europe’s place in 21st century global politics. -

Syria: a Million-Year Culture

SYRIA: A MILLION-YEAR CULTURE By Dr. Ali al-Qayyem Translated by: M. Allam Khoudr SYRIA: A MILLION-YEAR CULTURE Preface Syria: A Million-Year Culture Syrian Antiquities Antiquities & Museums Cultural Centers Cultural Directorates Theater Plastic Arts Culture Palace – Mahaba Festival Cinema Syria, its Civilizational and Cultural Achievements By Dr. Riadh Na'san Agha Minister of Culture Located between the Mediterranean, Mesopotamia, Asia Minor and the Arabian Peninsula, Syria has been since prehistoric times a natural and advanced civilizational, cultural, intellectual and artistic junction for these regions. Syria has, therefore, become a bridge and a meeting point for the most important of world thoughts, creativities and ingenuities, illuminating regions of the Ancient Orient with the glamour of its indigenous development and strongly and actively influencing the course of their civilizations. Throughout history Syria has fully realized its civilizational, intellectual and cultural mission, which reflects the most outstanding development of its civilization and turns its heritage into a multifarious and multifaceted human heritage, marked by openness, tolerance, marriage of thoughts and exchange of knowledge, sciences and cultures. Syria has long been a scene for development of inventions and human settlement along the banks of its big rivers, including the North Great River, the Orontes Basin, the Euphrates and Khabur Rivers as well as the Syrian steppe. Not only did the "Acheulean" culture emerge in Syria, but also agriculture, domestication of animals, prototype of roundhouses and villages were first born. It is here, in Syria, where civilization first evolved and people began trading agricultural products, developing pottery, shaping metals and producing bronze. -

ETANA Hezbollah + Druze.Indd

DIVIDE AND CONQUER THE GROWING HEZBOLLAH THREAT TO THE DRUZE A COLLABORATION BETWEEN THE MIDDLE EAST INSTITUTE AND ETANA SYRIA OCTOBER 2019 POLICY PAPER 2019-20 CONTENTS * 3 SUMMARY * 4 KEY POINTS * 6 INTRODUCTION * 6 SYRIA * 8 LEBANON * 10 GOLAN HEIGHTS * 13 CONCLUSION Cover photo: Druze men in the Israeli-annexed Golan Heights look out © The Middle East Institute across the southwestern Syrian province of Quneitra, visible across the border on July 7, 2018. (Photo by JALAA MAREY/AFP/Getty Images) The Middle East Institute Contents photos: Hezbollah fighters carry flags as they parade in a southern suburb of Beirut to mark al-Quds Day on May 31, 2019. (Photo by 1763 N Street NW ANWAR AMRO/AFP/Getty Images) Washington, D.C. 20036 SUMMARY Deep political, familial, and religious ties have allowed Druze communities across the Levant to remain largely unified against external threats, but eight years of vio- lence in Syria and a coordinated campaign by the re- gime and its allies now threaten to destabilize regional Druze politics and erode the sect’s political and military power. An Iranian-backed campaign by Hezbollah to incite inter-Druze violence in Lebanon has curtailed this unity, laying the groundwork for Hezbollah to expand into Syria’s Suwayda province with impunity. Hezbollah’s push to create inter-sect strife has extend- ed from Beirut to the occupied Golan Heights to Su- wayda, placing the region’s Druze in a greatly weakened position. This risk is particularly pronounced in Suwayda province, where attempts by Hezbollah and the regime to change the military and political reality on the ground have led to a major shift in power dynamics there, with Hezbollah now affiliated with 60% of armed groups in the province. -

The Blacklist

THE BLACKLIST Violations committed by the most prominent Syrian regime figures and how to bring them to justice The Blacklist violations committed by the most prominent Syrian Regime figures and how to bring them to justice The Blacklist, violations committed by the most prominent Syrian Re- gime figures and how to bring them to justice First published in the US 2019 by Pro-Justice 8725 Ginger Snap Lane, San Diego, CA 92129 Email. [email protected] Tel. +18588886410 ISBN: 978-605-7896-11-7 Copyright © Pro-justice All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of Pro-justice Pro-justice is a non-profit that seeks to maintain the principle of accountabil- ity and preclude impunity for major war criminal and human rights violators in societies that suffer from or have just exited civil wars and natural disasters, with special focus on the Middles East and Syria. Visit www.pro-justice.org to read more about pro-justice activities and pub- lications The Blacklist violations committed by the most prominent Syrian Regime figures and how to bring them to justice Foreword More than eight years have passed since Syrians took to the streets as part of a peaceful movement demanding freedom and human dignity. Since then, the Syrian government has continued to resist the laws of inevitable transformation, trying in vain to stop the process of political development and reform through its levers of killing and repression. -

Festering Grievances and the Return to Arms in Southern Syria

Festering Grievances and the Return to Arms in Southern Syria Abdullah Al-Jabassini Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 07 April 2020 2020/06 © European University Institute 2020 Content and individual chapters © Abdullah Al-Jabassini, 2020 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2020/06 07 April 2020 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu Festering Grievances and the Return to Arms in Southern Syria Abdullah Al-Jabassini* * Abdullah Al-Jabassini is a PhD candidate in International Relations at the University of Kent. His doctoral research investigates the relationship between tribalism, rebel governance and civil resistance to rebel organisations with a focus on Daraa governorate, southern Syria. He is also a researcher for the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project at the Middle East Directions Programme of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 2 1. -

Landforms of Al Kraa and Al Lajat Basaltic Sheets Between Om Al Zeton and Majadel Towns, Shahba District

Damascus University Journal, Vol.33 No.1 ,2017 Ghazwan Salloum Landforms of Al Kraa and Al Lajat Basaltic Sheets between Om Al Zeton and Majadel Towns, Shahba District Dr. Ghazwan Salloum* Abstract The area chosen for study is characterized by many typical emerging phenomenon related to basaltic sheets. The newest phenomena (B4Q4) can be described as having a rough surface and an angular landscape. They belong to type A a. They have messy morphological scene like hummock scoria, lava, cumulonimbus, subsiding, basaltic domes and scoria. The prominent rocks are formed from mixed hard substances. They correspond spatially with Al Akraa. Its source is Cone Shehan. The older phenomena (B5Q4) has comparatively a smooth surface, it belongs to (Pa hoe hoe). It source cones is hills of Majadel. Their surface is characterized by ropy lava, cracking convex hills or Lava –rise hills. They are separated by elongate paths (drops below it several meters). Both phenomena belong to Holocene from the Quaternary. Surface form creation is related to Lava nature and its physical and chemical characteristics: like viscosity, acidity, topographic old surface, geomorphic process (cooling – solid – interflow – surface cracking). Although both phenomena have the same chemical substances but they formed quite different scenes. This can be explained by the content of Si, the initial cooling degree, and viscosity of substances. The morphological characteristics of Al Kraa sheet was more viscous and variable (basalt and scoria) compared to that of Al Lajat sheet where basalt is dominant. * Department of Geographic - Faculty of Arts and Human Sciences- University of Damascus For the paper in Arabic see pages (173-204). -

To Read and Download, Click Here

INVESTMENT IN INTRASTATE CONFLICTS )1( “Assad’s Authorities” and “ISIS” in Sweida Governorate INVESTMENT IN INTRASTATE CONFLICTS )1(“Assad’s Authorities” and “ISIS” in Sweida Governorate Book Title: INVESTMENT IN INTRASTATE CONFLICTS (1) “Assad’s Authorities” and “ISIS” in Sweida Governorate Researchers: Yousef Fakher Eddin & Homam Al- Khateeb Legal Revision by: Lawyer: Anwar Al-Bonni Translated by: Ruba Khadamaljamei First Edition: May 2020 ) 1( Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Researches - Democratic Republic Studies Center All rights reserved for Syrian Center for Legal Studies and Researches www.sl-center.org and Democratic Republic Studies Center www.drsc-sy.org (2( INVESTMENT IN INTRASTATE CONFLICTS )1( “Assad’s Authorities” and “ISIS” in Sweida Governorate As we share with whom we thank the same concept that justice stands as the fine line separating between to be or not to be principle; therefore, our thankfulness is just an opportunity to assert this shared concept. We extend our thanks to who reviewed this study and added significant remarks and notes to clarify the objectivity as a base in it, who is the lawyer Anwar Al-Bonni and the researcher: “Haditha Amer”. Thanks to the journalist Rayan Marouf for cooperating with us, as our conversation with him was so useful. Thanks to all witnesses whose circumstances hinder them from telling their names openly, and for whoever helped us in this regard. Certainly, readership should keep in mind that the two scholars who authored this study are the only responsible ones for any error, mistake or shortcoming that might occur in it and they hope their study might be useful for anyone. -

Stone Structures in the Syrian Desert

Stone structures in the Syrian Desert Amelia Carolina Sparavigna Dipartimento di Fisica, Politecnico di Torino, Torino, Italy An arid land, known as the Syrian Desert, is covering a large part of the Middle East. In the past, this harsh environment, characterized by huge lava fields, the “harraat”, was considered as a barrier between Levant and Mesopotamia. When we observe this desert from space, we discover that it is crossed by some stone structures, the “desert kites”, which were the Neolithic traps for the game. Several stone circles are visible too, as many Stonehenge sites dispersed in the desert landscape. The Syrian Desert is an arid land of south-western Asia, extending from the northern Arabian Peninsula to the eastern Jordan, southern Syria, and western Iraq, largely covered by lava fields. Considered in the past as a barrier between Levant and Mesopotamia, it is now crossed by several routes and pipelines. This desert possesses two volcanic regions. One is the Jabal al-Druze, in the As-Suwayda Governorate. This volcanic field consists of a group of several basaltic volcanoes active from the lower-Pleistocene to the Holocene [1]. The other field is that of the Harrat Ash Shaam (in Arabic, the lava fields are the harraat, sing. harrah; before a name, harrat), including the Es-Safa volcano, in the South of Syria, south-east of Damascus. According to the Global Volcanism Program, the lava field contains several Holocene volcanic vents. The web site is telling that a boiling lava lake was also present in the mid 19th century [2]. When we observe this desert from space, we discover that this harsh environment was probably quite populated in ancient times. -

REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA Humanitarian Assistance in Syria

Humanitarian concerns: An estimated 9.3 million people are in need of REGIONAL ANALYSIS SYRIA humanitarian assistance in Syria. The 2014 Syrian Humanitarian Assistance Response Plan (SHARP) requested USD 2.28 billion for aid provided from 03 July 2014 Damascus. As of June, only 27% of this funding had been secured. Without Part I – Syria further donor commitment, lifesaving assistance to vulnerable communities is expected to be cut drastically. Furthermore, with the summer arriving, Water is Content Part I This Regional Analysis of the Syria conflict (RAS) becoming a serious problem in terms of availability and quality. This contributes is now produced quarterly, replacing the monthly Overview to health concerns, with a reported increase in waterborne diseases, such as RAS of 2013. It seeks to bring together information Timeline 2014 Q2 main events from all sources in the region and provide holistic acute diarrhoea in Damascus, Rural Damascus, Deir-ez-Zor and Al- Hasakeh. analysis of the overall Syria crisis. Operational constraints Protection continues to be a major issue in areas affected by violence, with a Humanitarian profile While Part I focuses on the situation within Syria, rise in indiscriminate attacks on civilians, including children. The number of Part II covers the impact of the crisis on Armed conflict children killed has increased disproportionately since mid-February, notably in neighbouring countries. Displacement profile Aleppo and Dar’a. Food remains an area of concern due to the lack of More information on how to use this document can Country sectoral analysis livelihoods, rising prices, population movements and constriction of aid. be found on page 69. -

The Druze of Sweida: the Return of the Regime Hinges on Regional and Local Conflicts

The Druze of Sweida: the Return of the Regime Hinges on Regional and Local Conflicts Mahmoud al-Lababidi Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria (WPCS) Research Project Report 28 August 2019 2019/12 © European University Institute 2019 Content and individual chapters © Mahmoud al-Lababidi, 2019 This work has been published by the European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the authors. If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. Requests should be addressed to [email protected]. Views expressed in this publication reflect the opinion of individual authors and not those of the European University Institute. Middle East Directions Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies Research Project Report RSCAS/Middle East Directions 2019/12 28 August 2019 European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ cadmus.eui.eu The Druze of Sweida: the Return of the Regime Hinges on Regional and Local Conflicts Mahmoud al-Lababidi* * Mahmoud al-Lababidi is a Syrian researcher working on the Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria project (WPCS) within the Middle East Directions Programme, which is supervised by the Robert Schuman Centre for Postgraduate Studies at the European University Institute in Florence. His work focuses on the war economy in Syria and the areas under regime control. This research paper was published in Arabic on 1 August 2019 (http://medirections.com/).