The Druze of Sweida: the Return of the Regime Hinges on Regional and Local Conflicts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Foreign Policy Trends in the GCC States

Autumn 2017 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Foreign Policy Trends in the GCC States Featuring H.E. Sheikh Mohammed bin Abdulrahman Al-Thani Minister of Foreign Affairs State of Qatar H.E. Sayyid Badr bin Hamad Albusaidi Secretary General of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs Sultanate of Oman H.E. Ambassador Michele Cervone d’Urso Head of Delegation to Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman & Qatar European Union Foreword by Kristian Coates Ulrichsen OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Co-Editor: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Adam Rasmi Associate Editor: Rana AlMutawa Research Associate: Lolwah Al-Khater Research Associate: Jalal Imran Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Copyright © 2017 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2017 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication. -

On the Present-Day Veneration of Sacred Trees in the Holy Land

ON THE PRESENT-DAY VENERATION OF SACRED TREES IN THE HOLY LAND Amots Dafni Abstract: This article surveys the current pervasiveness of the phenomenon of sacred trees in the Holy Land, with special reference to the official attitudes of local religious leaders and the attitudes of Muslims in comparison with the Druze as well as in monotheism vs. polytheism. Field data regarding the rea- sons for the sanctification of trees and the common beliefs and rituals related to them are described, comparing the form which the phenomenon takes among different ethnic groups. In addition, I discuss the temporal and spatial changes in the magnitude of tree worship in Northern Israel, its syncretic aspects, and its future. Key words: Holy land, sacred tree, tree veneration INTRODUCTION Trees have always been regarded as the first temples of the gods, and sacred groves as their first place of worship and both were held in utmost reverence in the past (Pliny 1945: 12.2.3; Quantz 1898: 471; Porteous 1928: 190). Thus, it is not surprising that individual as well as groups of sacred trees have been a characteristic of almost every culture and religion that has existed in places where trees can grow (Philpot 1897: 4; Quantz 1898: 467; Chandran & Hughes 1997: 414). It is not uncommon to find traces of tree worship in the Middle East, as well. However, as William Robertson-Smith (1889: 187) noted, “there is no reason to think that any of the great Semitic cults developed out of tree worship”. It has already been recognized that trees are not worshipped for them- selves but for what is revealed through them, for what they imply and signify (Eliade 1958: 268; Zahan 1979: 28), and, especially, for various powers attrib- uted to them (Millar et al. -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

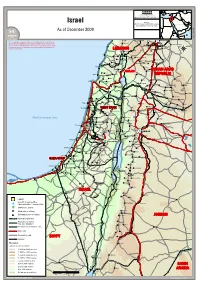

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral Report District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher '&# Aley Chouf Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 4 Electoral District: Aley and Chouf Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS’s work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, John McCabe, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report. 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary The Lebanese parliament agreed to hold parliamentary elections in 2018—nine years after the previous ones. Voters in Aley and Chouf showed strong loyalty toward their sectarian parties and high preferences for candidates of their own sectarian group. -

The New Lebanese Government

The New Lebanese Government Assessment Report by the Lebanese Information Center July 2011 www.licus.org cleared for public release /D1 Nearly five months after his appointment as Prime Minister, Najib Mikati finally formed the Lebanese Cabinet on June 13, 2011. The 30-member cabinet, in which Hezbollah and its allies hold a majority, was formed following arduous negotiations between the new majority, constituted of the March 8 parties, and their allies. The March 14 alliance had announced that it will not take part in the Mikati cabinet following the forced collapse of Hariri’s unity government. Furthermore, appointed Druze Minister of State, Talal Arslan, announced his immediate resignation from the government to protest not being given a portfolio. Despite clearly [and exclusively] representing the Pro-Syrian camp, Prime Minister Mikati announced that his government is “a government for all Lebanese, no matter what party they support, be it the majority or the opposition.” Contents The New Government – Statistics in Brief ..................................................................................................2 Cabinet Members .................................................................................................................................... 2 Composition by Party Affiliation ........................................................................................................... 3 Composition by Coalition ...................................................................................................................... -

Landscapes of NE-Africa and W-Asia—Landscape Archaeology As a Tool for Socio-Economic History in Arid Landscapes

land Article ‘Un-Central’ Landscapes of NE-Africa and W-Asia—Landscape Archaeology as a Tool for Socio-Economic History in Arid Landscapes Anna-Katharina Rieger Institute of Ancient History and Classical Antiquities, University of Graz, A-8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected]; Tel.: +43-316-380-2391 Received: 6 November 2018; Accepted: 17 December 2018; Published: 22 December 2018 Abstract: Arid regions in the Old World Dry Belt are assumed to be marginal regions, not only in ecological terms, but also economically and socially. Such views in geography, archaeology, and sociology are—despite the real limits of living in arid landscapes—partly influenced by derivates of Central Place Theory as developed for European medieval city-based economies. For other historical time periods and regions, this narrative inhibited socio-economic research with data-based and non-biased approaches. This paper aims, in two arid Graeco-Roman landscapes, to show how far approaches from landscape archaeology and social network analysis combined with the “small world phenomenon” can help to overcome a dichotomic view on core places and their areas, and understand settlement patterns and economic practices in a nuanced way. With Hauran in Southern Syria and Marmarica in NW-Egypt, I revise the concept of marginality, and look for qualitatively and spatially defined relationships between settlements, for both resource management and social organization. This ‘un-central’ perspective on arid landscapes provides insights on how arid regions functioned economically and socially due to a particular spatial concept and connection with their (scarce) resources, mainly water. Keywords: aridity; marginality; landscape archaeology; Marmarica (NW-Egypt); Hauran (Syria/ Jordan); Graeco-Roman period; spatial scales in networks; network relationship qualities; interaction; resource management 1. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

The Druze: Culture, History and Mission

The Druze A New Cultural and Historical Appreciation Abbas Halabi 2013 www.garnetpublishing.co.uk 1 The Druze Published by Garnet Publishing Limited 8 Southern Court South Street Reading RG1 4QS UK www.garnetpublishing.co.uk www.twitter.com/Garnetpub www.facebook.com/Garnetpub blog.garnetpublishing.co.uk Copyright © Abbas Halabi, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. First Edition 2013 ISBN: 9781859643532 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Jacket design by Garnet Publishing Typeset by Samantha Barden Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected] 2 To Karl-Abbas, my first grandson And the future generation of my family 3 Preface Foreword Introduction Chapter 1 Human geography Chapter 2 The history of the Druze, 1017–1943 Chapter 3 Communal and social organization Chapter 4 Traditional culture and the meaning of al-Adhā feast Chapter 5 Civil status law Chapter 6 The diaspora and cultural expansion Chapter 7 The political role of the Druze from independence to the present time Chapter 8 The Druze message: plurality and unity Summary and conclusion Appendix 1 The impact of European influences on the Druze community: “The new look” Appendix 2 Sheikh Halīm Taqī al-Dīn: a man of knowledge, -

Genetic Heterogeneity of Beta Thalassemia in Lebanon Reflects

doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00138.x Genetic Heterogeneity of Beta Thalassemia in Lebanon Reflects Historic and Recent Population Migration N. J. Makhoul1,R.S.Wells2,H.Kaspar1,3,H.Shbaklo3,A.Taher1,4,N.Chakar1 and P. A. Zalloua1,5∗ 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon 2Oxford University, London, UK 3Genetics Research Laboratory, Chronic Care Center, Beirut, Lebanon 4Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon 5Program for Population Genetics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, USA Summary Beta thalassemia is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by reduced (β+)orabsent (β0) beta-globin chain synthesis. In Lebanon it is the most predominant genetic defect. In this study we investigated the religious and geographic distribution of the β-thalassemia mutations identified in Lebanon, and traced their precise origins. A total of 520 β-globin chromosomes from patients of different religious and regional backgrounds was studied. Beta thalassemia mutations were identified using Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS) PCR or direct gene sequencing. Six (IVS-I-110, IVS-I-1, IVS-I-6, IVS-II-1, cd 5 and the C>T substitution at cd 29) out of 20 β-globin defects identified accounted for more than 86% of the total β-thalassemia chromosomes. Sunni Muslims had the highest β-thalassemia carrier rate and presented the greatest heterogeneity, with 16 different mutations. Shiite Muslims followed closely with 13 mutations, whereas Maronites represented 11.9% of all β-thalassemic subjects and carried 7 different mutations. RFLP haplotype analysis showed that the observed genetic diversity originated from both new mutational events and gene flow from population migration. -

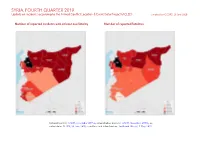

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on Incidents According to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) Compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020

SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) compiled by ACCORD, 23 June 2020 Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality Number of reported fatalities National borders: GADM, November 2015a; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015b; in- cident data: ACLED, 20 June 2020; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Contents Conflict incidents by category Number of Number of reported fatalities 1 Number of Number of Category incidents with at incidents fatalities Number of reported incidents with at least one fatality 1 least one fatality Explosions / Remote Conflict incidents by category 2 3058 397 1256 violence Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 2 Battles 1023 414 2211 Strategic developments 528 6 10 Methodology 3 Violence against civilians 327 210 305 Conflict incidents per province 4 Protests 169 1 9 Riots 8 1 1 Localization of conflict incidents 4 Total 5113 1029 3792 Disclaimer 8 This table is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). Development of conflict incidents from December 2017 to December 2019 This graph is based on data from ACLED (datasets used: ACLED, 20 June 2020). 2 SYRIA, FOURTH QUARTER 2019: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) COMPILED BY ACCORD, 23 JUNE 2020 Methodology GADM. Incidents that could not be located are ignored. The numbers included in this overview might therefore differ from the original ACLED data. -

1St-Baghdad-International-Water-Conference-Modern-Technologies-CA Lebanon-WO-Videos

th 13th -14 March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Modern Methods of Remote Data collection in Transboundary Rivers Yarmouk River study case Dr. Chadi Abdallah CNRS-L Lebanon Introduction WATER is a precious natural resource and at the same time complex to manage. 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE 24Font width Times New Roman Font type Take in consider the transparency of the color 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE • Difficulty to acquire in-situ data • Sensitivity in data exchange • Contradiction and gaps in data o Area of the watershed (varies from 6,700 Km2 to 8,378 Km2) o Length of the river (varies from 40 Km to 143 Km) o Flow data (variable, not always clear) • Unavailable major datasets o Long-term accurate precipitation o Flow gauging stations o Springs discharge o Wells extraction o Dams actual retention o Detailed LUC 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Digital Globe-ESRI- GeoEye (0.5m/2011& CORONA (2m/1966) SPOT (10m/2009) 2019) LUC 1966 CWR estimation LUC 2011& 2020 Landsat 5 to 8 (30m/1982- 2020) MODIS-MOD16 CHIRPS (5Km/1980-2015) 150 images (1Km/2000-2020) 493 images Dams actual retention 255 images Precipitation CWR estimation Evapotranspiration LST, NDVI, ET, SMI 13th -14th March 2021 1ST BAGHDAD INTERNATIONAL WATER CONFERENCE Jabal Al Qaly'a Yarmouk River Ash Shaykh .! Raqqad Area: 7,386 Km2 • Quneitra .! Jbab .! Length of Main Tributary from • Sanameyn -

Gulf Affairs

Autumn 2016 A Publication based at St Antony’s College Identity & Culture in the 21st Century Gulf Featuring H.E. Salah bin Ghanem Al Ali Minister of Culture and Sports State of Qatar H.E. Shaikha Mai Al-Khalifa President Bahrain Authority for Culture & Antiquities Ali Al-Youha Secretary General Kuwait National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters Nada Al Hassan Chief of Arab States Unit UNESCO Foreword by Abdulaziz Saud Al-Babtain OxGAPS | Oxford Gulf & Arabian Peninsula Studies Forum OxGAPS is a University of Oxford platform based at St Antony’s College promoting interdisciplinary research and dialogue on the pressing issues facing the region. Senior Member: Dr. Eugene Rogan Committee: Chairman & Managing Editor: Suliman Al-Atiqi Vice Chairman & Partnerships: Adel Hamaizia Editor: Jamie Etheridge Chief Copy Editor: Jack Hoover Arabic Content Lead: Lolwah Al-Khater Head of Outreach: Mohammed Al-Dubayan Communications Manager: Aisha Fakhroo Broadcasting & Archiving Officer: Oliver Ramsay Gray Research Assistant: Matthew Greene Copyright © 2016 OxGAPS Forum All rights reserved Autumn 2016 Gulf Affairs is an independent, non-partisan journal organized by OxGAPS, with the aim of bridging the voices of scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers to further knowledge and dialogue on pressing issues, challenges and opportunities facing the six member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessar- ily represent those of OxGAPS, St Antony’s College, or the University of Oxford. Contact Details: OxGAPS Forum 62 Woodstock Road Oxford, OX2 6JF, UK Fax: +44 (0)1865 595770 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oxgaps.org Design and Layout by B’s Graphic Communication.