Religion and Politics in Contemporary Lebanon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Druze: Culture, History and Mission

The Druze A New Cultural and Historical Appreciation Abbas Halabi 2013 www.garnetpublishing.co.uk 1 The Druze Published by Garnet Publishing Limited 8 Southern Court South Street Reading RG1 4QS UK www.garnetpublishing.co.uk www.twitter.com/Garnetpub www.facebook.com/Garnetpub blog.garnetpublishing.co.uk Copyright © Abbas Halabi, 2013 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. First Edition 2013 ISBN: 9781859643532 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Jacket design by Garnet Publishing Typeset by Samantha Barden Printed and bound in Lebanon by International Press: [email protected] 2 To Karl-Abbas, my first grandson And the future generation of my family 3 Preface Foreword Introduction Chapter 1 Human geography Chapter 2 The history of the Druze, 1017–1943 Chapter 3 Communal and social organization Chapter 4 Traditional culture and the meaning of al-Adhā feast Chapter 5 Civil status law Chapter 6 The diaspora and cultural expansion Chapter 7 The political role of the Druze from independence to the present time Chapter 8 The Druze message: plurality and unity Summary and conclusion Appendix 1 The impact of European influences on the Druze community: “The new look” Appendix 2 Sheikh Halīm Taqī al-Dīn: a man of knowledge, -

Genetic Heterogeneity of Beta Thalassemia in Lebanon Reflects

doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2004.00138.x Genetic Heterogeneity of Beta Thalassemia in Lebanon Reflects Historic and Recent Population Migration N. J. Makhoul1,R.S.Wells2,H.Kaspar1,3,H.Shbaklo3,A.Taher1,4,N.Chakar1 and P. A. Zalloua1,5∗ 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon 2Oxford University, London, UK 3Genetics Research Laboratory, Chronic Care Center, Beirut, Lebanon 4Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon 5Program for Population Genetics, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, USA Summary Beta thalassemia is an autosomal recessive disorder characterized by reduced (β+)orabsent (β0) beta-globin chain synthesis. In Lebanon it is the most predominant genetic defect. In this study we investigated the religious and geographic distribution of the β-thalassemia mutations identified in Lebanon, and traced their precise origins. A total of 520 β-globin chromosomes from patients of different religious and regional backgrounds was studied. Beta thalassemia mutations were identified using Amplification Refractory Mutation System (ARMS) PCR or direct gene sequencing. Six (IVS-I-110, IVS-I-1, IVS-I-6, IVS-II-1, cd 5 and the C>T substitution at cd 29) out of 20 β-globin defects identified accounted for more than 86% of the total β-thalassemia chromosomes. Sunni Muslims had the highest β-thalassemia carrier rate and presented the greatest heterogeneity, with 16 different mutations. Shiite Muslims followed closely with 13 mutations, whereas Maronites represented 11.9% of all β-thalassemic subjects and carried 7 different mutations. RFLP haplotype analysis showed that the observed genetic diversity originated from both new mutational events and gene flow from population migration. -

The Mardinite Community in Lebanon: Migration of Mardin’S People

Report No: 208, March 2017 THE MARDINITE COMMUNITY IN LEBANON: MIGRATION OF MARDIN’S PEOPLE ORTADOĞU STRATEJİK ARAŞTIRMALAR MERKEZİ CENTER FOR MIDDLE EASTERN STRATEGIC STUDIES ORSAM Süleyman Nazif Sokak No: 12-B Çankaya / Ankara Tel: 0 (312) 430 26 09 Fax: 0 (312) 430 39 48 www.orsam.org.tr, [email protected] THE MARDINITE COMMUNITY IN LEBANON: MIGRATION OF MARDIN’S PEOPLE ORSAM Report No: 208 March 2017 ISBN: 978-605-9157-17-9 Ankara - TURKEY ORSAM © 2017 Content of this report is copyrighted to ORSAM. Except reasonable and partial quotation and use under the Act No. 5846, Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works, via proper citation, the content may not be used or republished without prior permission by ORSAM. The views expressed in this report reflect only the opinions of its authors and do not represent the institutional opinion of ORSAM. By: Ayşe Selcan ÖZDEMİRCİ, Middle East Instutute Sakarya University ORSAM 2 Report No: 208, March 2017 İçindekiler Preface ................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 10 1. THE MARDINITES AS A SUBALTERN GROUP .............................................................................. -

Reconstructing Druze Population History Scarlett Marshall1, Ranajit Das2, Mehdi Pirooznia3 & Eran Elhaik4

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Reconstructing Druze population history Scarlett Marshall1, Ranajit Das2, Mehdi Pirooznia3 & Eran Elhaik4 The Druze are an aggregate of communities in the Levant and Near East living almost exclusively in Received: 27 April 2016 the mountains of Syria, Lebanon and Israel whose ~1000 year old religion formally opposes mixed Accepted: 05 October 2016 marriages and conversions. Despite increasing interest in genetics of the population structure of the Published: 16 November 2016 Druze, their population history remains unknown. We investigated the genetic relationships between Israeli Druze and both modern and ancient populations. We evaluated our findings in light of three hypotheses purporting to explain Druze history that posit Arabian, Persian or mixed Near Eastern- Levantine roots. The biogeographical analysis localised proto-Druze to the mountainous regions of southeastern Turkey, northern Iraq and southeast Syria and their descendants clustered along a trajectory between these two regions. The mixed Near Eastern–Middle Eastern localisation of the Druze, shown using both modern and ancient DNA data, is distinct from that of neighbouring Syrians, Palestinians and most of the Lebanese, who exhibit a high affinity to the Levant. Druze biogeographic affinity, migration patterns, time of emergence and genetic similarity to Near Eastern populations are highly suggestive of Armenian-Turkish ancestries for the proto-Druze. The population history of the Druze people, who accepted Druzism around the 11th century A.D., remains a fascinating question in history, cultural anthropology and genetics. Contemporary Druze comprise an aggre- gate of Levantine and Near Eastern communities residing almost exclusively in the mountain regions of Syria (500,000), Lebanon (215,000), Israel (136,000) and Jordan (20,000), although with an increasingly large diaspora in the USA1–3. -

Lebanon's Political Dynamics

Lebanon’s political dynamics: population, religion and the region Salma Mahmood * As the Lebanese political crisis deepens, it becomes imperative to examine its roots and find out if there is a pattern to the present predicament, in examination of the past. Upon tracing the historical background, it becomes evident that the Lebanese socio-political system has been influenced by three major factors: the population demographic, regional atmosphere and sub-national identity politics. Though not an anomaly, Lebanon is one of the few remaining consociational democracies1 in the world. However, with the current political deadlock in the country, it is questionable how long this system will sustain. This article will take a thematic approach and begin with the historical precedent in each context linking it to the current situation for a better comprehension of the multifaceted nuclei shaping the country‟s turbulent course. Population Demographics Majority of the causal explanations cited to comprehend the contemporary religio-political problems confronting the Middle East have their roots in the imperialist games. Hence, it is in the post First World War French mandate that we find the foundations of the Lebanese paradigm. In 1919, the French decision was taken to concede the Maronite demands and grant the state of a Greater Lebanon. Previously, under the Ottoman rule, there existed an autonomous district of Lebanon consisting solely of Mount Lebanon and a 1914 population of about 400,000; four-fifth Christian and one-fifth Muslim. Amongst -

Proquest Dissertations

Reincarnation, marriage, and memory: Negotiating sectarian identity among the Druze of Syria Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bennett, Marjorie Anne, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 10:45:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/283987 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

The Crisis in Lebanon: a Test of Consociational Theory

THE CRISIS IN LEBANON: A TEST OF CONSOCIATIONAL THEORY BY ROBERT G. CHALOUHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE COUNCIL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 1978 Copyright 1978 by Robert G. Chalouhi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my thanks to the members of my committee, especially to my adviser, Dr. Keith Legg, to whom I am deeply indebted for his invaluable assistance and guidance. This work is dedicated to my parents, brother, sister and families for continued encouragement and support and great confidence in me; to my parents-in-law for their kindness and concern; and especially to my wife Janie for her patient and skillful typing of this manuscript and for her much- needed energy and enthusiasm. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iii LIST OF TABLES vii ABSTRACT ix CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION 1 Applicability of the Model 5 Problems of System Change 8 Assumption of Subcultural Isolation and Uniformity 11 The Consociational Model Applied to Lebanon 12 Notes 22 CHAPTER II THE BEGINNINGS OF CONSOCIATIONALISM: LEBANON IN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE. 25 The Phoenicians 27 The Birth of Islam 29 The Crusaders 31 The Ottoman Empire 33 Bashir II and the Role of External Powers 38 The Qaim Maqamiya 41 The Mutasarrif iyah: Confessional Representation Institutionalized. 4 6 The French Mandate, 1918-1943: The Consolidation of Consociational Principles 52 Notes 63 CHAPTER III: THE OPERATION OF THE LEBANESE POLITICAL SYSTEM 72 Confessionalism and Proportionality: Nominal Actors and Formal Rules . 72 The National Pact 79 The Formal Institutions 82 Political Clientelism: "Real" Actors and Informal Rules The Politics of Preferment and Patronage 92 Notes 95 CHAPTER IV: CONSOCIATIONALISM PUT TO THE TEST: LEBANON IN THE FIFTIES AND SIXTIES. -

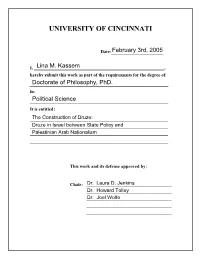

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ The Construction of Druze Ethnicity: Druze in Israel between State Policy and Palestinian Arab Nationalism A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTORATE OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science of the College of Arts and Sciences 2005 by Lina M. Kassem B.A. University of Cincinnati, 1991 M.A. University of Cincinnati, 1998 Committee Chair: Professor Laura Jenkins i ABSTRACT: Eric Hobsbawm argues that recently created nations in the Middle East, such as Israel or Jordan, must be novel. In most instances, these new nations and nationalism that goes along with them have been constructed through what Hobsbawm refers to as “invented traditions.” This thesis will build on Hobsbawm’s concept of “invented traditions,” as well as add one additional but essential national building tool especially in the Middle East, which is the military tradition. These traditions are used by the state of Israel to create a sense of shared identity. These “invented traditions” not only worked to cement together an Israeli Jewish sense of identity, they were also utilized to create a sub national identity for the Druze. The state of Israel, with the cooperation of the Druze elites, has attempted, with some success, to construct through its policies an ethnic identity for the Druze separate from their Arab identity. -

The Sweet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-6-2016 The weetS Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon Chad Kassem Radwan Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Scholar Commons Citation Radwan, Chad Kassem, "The wS eet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon" (2016). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/6132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Sweet Burden: Constructing and Contesting Druze Heritage and Identity in Lebanon by Chad Kassem Radwan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Kevin A. Yelvington, D.Phil Elizabeth Aranda, Ph.D. Abdelwahab Hechiche, Ph.D. Antoinette Jackson, Ph.D. John Napora, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 1, 2016 Keywords: preservation, discursive approach, educational resources, reincarnation Copyright © 2016, Chad Radwan Dedication Before having written a single word of this dissertation it was apparent that my success in this undertaking, as in any other, has always been the product of my parents, Kassem and Wafaa Radwan. Thank you for showing me the value of dedication, selflessness, and truly, truly hard work. I have always harbored a strong sense of compassion for each and every person I have had the opportunity to come across in my life and I have both of you to thank for understanding this most essential human sentiment. -

DIVORCE AS a LIVED EXPERIENCE AMONG the LEBANESE DRUZE: a STUDY of COURT RECORDS and PROCEEDINGS LUBNA TARABEY Background Family

Tarabey, Divorce among Lebanese Druze DIVORCE AS A LIVED EXPERIENCE AMONG THE LEBANESE DRUZE: A STUDY OF COURT RECORDS AND PROCEEDINGS LUBNA TARABEY Abstract. The Druze community in Lebanon constitutes an esoteric religious community characterized by a rejection of any challenge to traditional family values. Research on family relations among this group is scant because of their refusal to disclose information to others. This article looks at one aspect of Druze family life – divorce through a study of court records, proceedings and mediation. The research revealed that consent is favored, even within conflict, with very few contested divorces appearing before the court. Druze women assert their legal rights to divorce, in court negotiations are exhaustive but very rare, and the aftermath of divorce continues to haunt women when it comes to child visiting rights. Change in the particularities of divorce are noticeable as perceived by the judge and mediator. Nevertheless, gender inequalities persist and legal systems that continue to discriminate against women dominate, although divorce laws have become more progressive. Key words. Divorce, Druze, Family Conflict, Gender, Mediation. Background Family life forms perhaps one of the most complex webs of relationships to be found within a single social group, involving a lot of caring, self-sacrifice, love and support. Yet, it also has a less bright side to it. Families can also become arenas for hate, violence, abuse and conflict. This murkier side of family life manifests itself in all its aspects in divorce, the lived and experienced reality that in one way or another pulls all family members and children into conflict. -

Conflict on Mount Lebanon: Collective Memory and the War of the Mountain

CONFLICT ON MOUNT LEBANON: COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND THE WAR OF THE MOUNTAIN A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Makram G Rabah, M.A. Washington, D.C. December 12, 2016 Copyright 2016 by Makram G Rabah All Rights Reserved ii CONFLICT ON MOUNT LEBANON COLLECTIVE MEMORY AND THE WAR OF THE MOUNTAIN Makram G Rabah, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Osama Abi-Mershed, Ph.D. ABSTRACT The Druze and Maronites, the founding communities of modern Lebanon, have clashed on more than one occasion over the past two centuries earning them the reputation of being primordial enemies. This study is an attempt to gauge the impact that collective memory had on determining the course and the nature of the conflict between these communities in Mount Lebanon in what came to be called the War of the Mountain in 1982. This dissertation will attempt to reconstruct, perhaps for the first time, the events of the 1982 war through the framework of collective remembrance. In doing so, the thesis hopes to achieve better understanding of the conflict as well as the consequences it had on the two communities and beyond, most importantly the post-war reconciliation process; which maybe applicable to other communal conflicts in the region. This dissertation extensively utilizes oral history, in some of its parts, to explore how collective memory has shaped the conflict between the two communities, by interviewing a number of informants from both (inside and outside) the Druze and Maronite communities who have been involved or were witnesses to the conflict. -

Massacres, Desecration, and Iconoclasm in Lebanon's Mountain

Crimes on Sacred Ground: Massacres, Desecration, and Iconoclasm in Lebanon’s Mountain War 1983-1984 Matthew Hinson Honors Thesis Submitted to the Department of History, Georgetown University Advisor: Professor Judith Tucker Honors Program Chair: Professor Amy Leonard 8 May 2017 Hinson 2 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to the victims of civil wars past and present in the hopes that they find sanctuary, sacred or otherwise. Hinson 3 Acknowledgements There are many people to whom I am grateful for their contributions to this thesis. First and foremost, this project would not be complete without the thoughtful comments and kindness of my faculty advisor, Professor Judith Tucker. I must thank Professor Amy Leonard and my fellow students in the History Honors Seminar. It has been an incredibly year, and your comments have been invaluable. Professor Tommaso Astarita and Dean Anthony Pirrotti have been more than helpful in my registration and participation in history courses throughout the years, including the History Honors Seminar. And of course, thank you to the special people out there (you know who you are) as well as the countless friends forced me to work on this thesis and accompanied me in the many long nights in Lauinger Library (you also know who you are). Hinson 4 I hereby grant to Georgetown University and its agents the non-exclusive, worldwide right to reproduce, distribute, display and transmit my thesis or dissertation in such tangible and electronic formats as may be in existence now or developed in the future. I retain all ownership rights to the copyright of the thesis or dissertation, including the right to use it in whole or in part in future works.