Children's Understanding of the Universal Quantifier WH+Mo In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

AIX Globalization

AIX Version 7.1 AIX globalization IBM Note Before using this information and the product it supports, read the information in “Notices” on page 233 . This edition applies to AIX Version 7.1 and to all subsequent releases and modifications until otherwise indicated in new editions. © Copyright International Business Machines Corporation 2010, 2018. US Government Users Restricted Rights – Use, duplication or disclosure restricted by GSA ADP Schedule Contract with IBM Corp. Contents About this document............................................................................................vii Highlighting.................................................................................................................................................vii Case-sensitivity in AIX................................................................................................................................vii ISO 9000.....................................................................................................................................................vii AIX globalization...................................................................................................1 What's new...................................................................................................................................................1 Separation of messages from programs..................................................................................................... 1 Conversion between code sets............................................................................................................. -

Katakana Back

321“u” as in you “i” as in easy “a” as in father ウ イ アAAAaaa! “Oooo!” The water balloon was An easel holds your picture “AAAaaa!” cried the critter as cold as it splashed on his back! while you work on it or display it. he fell off the edge of the cliff. 654“ka” as in car “o” as in oak “e” as in red カか Katakana “ka” カ and オ hiragana “ka” か look a bit alike. an Olympic figure skater elevator doors 987“ke” as in Kevin “ku” as in cuckoo “ki” as in key ク キき ケ Katakana “ki” キ and a kangaroo a cool way to write7 seven (7) hiragana “ki” き look a bit alike. 12“shi” as in she 11“sa” as in saw 10 “ko” as in cocoa シ サ A sawhorse holds She tilted her head and smiled. wood while you cut it. コa cup of hot cocoa 15“so” as in so 14“se” as in set 13 “su” as in super セ When other kids said, せ “You only have one eye,” Katakana “se” and hiragana “se” he said, “So!” look a little alike. スIt’s Superman... er, super-critter. 18“tsu” as in cats 17“chi” as in cheer 16 “ta” as in tall チ タ Tw o children are the leaning tower of Pisa sliding down a slide. (In Japanese “tower” is pronounced (“ts” like cats and “u” like you) a cheerleader with a “ta” as in tall). 21“na” as in not 20“to” as in totem 19 “te” as in telephone ト テ a knife a totem pole a telephone pole and wires 24“ne” as in nest 23“nu” as in new 22 “ni” as in need ネ a nest on top of a tree a new way to write seven (7) The Japanese word for “two” is ni. -

Beginning Japanese for Professionals: Book 1

BEGINNING JAPANESE FOR PROFESSIONALS: BOOK 1 Emiko Konomi Beginning Japanese for Professionals: Book 1 Emiko Konomi Portland State University 2015 ii © 2018 Emiko Konomi This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License You are free to: • Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format • Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following terms: • Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. • NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes Published by Portland State University Library Portland, OR 97207-1151 Cover photo: courtesy of Katharine Ross iii Accessibility Statement PDXScholar supports the creation, use, and remixing of open educational resources (OER). Portland State University (PSU) Library acknowledges that many open educational resources are not created with accessibility in mind, which creates barriers to teaching and learning. PDXScholar is actively committed to increasing the accessibility and usability of the works we produce and/or host. We welcome feedback about accessibility issues our users encounter so that we can work to mitigate them. Please email us with your questions and comments at [email protected]. “Accessibility Statement” is a derivative of Accessibility Statement by BCcampus, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Accessibility of Beginning Japanese I A prior version of this document contained multiple accessibility issues. -

Haitian Creole – English Dictionary

+ + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary with Basic English – Haitian Creole Appendix Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo dp Dunwoody Press Kensington, Maryland, U.S.A. + + + + Haitian Creole – English Dictionary Copyright ©1993 by Jean Targète and Raphael G. Urciolo All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the Authors. All inquiries should be directed to: Dunwoody Press, P.O. Box 400, Kensington, MD, 20895 U.S.A. ISBN: 0-931745-75-6 Library of Congress Catalog Number: 93-71725 Compiled, edited, printed and bound in the United States of America Second Printing + + Introduction A variety of glossaries of Haitian Creole have been published either as appendices to descriptions of Haitian Creole or as booklets. As far as full- fledged Haitian Creole-English dictionaries are concerned, only one has been published and it is now more than ten years old. It is the compilers’ hope that this new dictionary will go a long way toward filling the vacuum existing in modern Creole lexicography. Innovations The following new features have been incorporated in this Haitian Creole- English dictionary. 1. The definite article that usually accompanies a noun is indicated. We urge the user to take note of the definite article singular ( a, la, an or lan ) which is shown for each noun. Lan has one variant: nan. -

International Language Environments Guide for Oracle® Solaris 11.4

International Language Environments ® Guide for Oracle Solaris 11.4 Part No: E61001 November 2020 International Language Environments Guide for Oracle Solaris 11.4 Part No: E61001 Copyright © 2011, 2020, Oracle and/or its affiliates. License Restrictions Warranty/Consequential Damages Disclaimer This software and related documentation are provided under a license agreement containing restrictions on use and disclosure and are protected by intellectual property laws. Except as expressly permitted in your license agreement or allowed by law, you may not use, copy, reproduce, translate, broadcast, modify, license, transmit, distribute, exhibit, perform, publish, or display any part, in any form, or by any means. Reverse engineering, disassembly, or decompilation of this software, unless required by law for interoperability, is prohibited. Warranty Disclaimer The information contained herein is subject to change without notice and is not warranted to be error-free. If you find any errors, please report them to us in writing. Restricted Rights Notice If this is software or related documentation that is delivered to the U.S. Government or anyone licensing it on behalf of the U.S. Government, then the following notice is applicable: U.S. GOVERNMENT END USERS: Oracle programs (including any operating system, integrated software, any programs embedded, installed or activated on delivered hardware, and modifications of such programs) and Oracle computer documentation or other Oracle data delivered to or accessed by U.S. Government end users are -

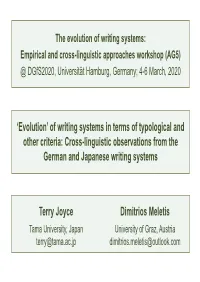

Of Writing Systems in Terms of Typological and Other Criteria: Cross-Linguistic Observations from the German and Japanese Writing Systems

The evolution of writing systems: Empirical and cross-linguistic approaches workshop (AG5) @ DGfS2020, Universität Hamburg, Germany; 4-6 March, 2020 ‘Evolution’ of writing systems in terms of typological and other criteria: Cross-linguistic observations from the German and Japanese writing systems Terry Joyce Dimitrios Meletis Tama University, Japan University of Graz, Austria [email protected] [email protected] Overview Opening remarks Selective sample of writing system (WS) typologies Alternative criteria for evaluating WSs Observations from German (GWS) + Japanese (JWS) Closing remarks Opening remarks 1: Chaos over basic terminology! Erring towards understatement, Gnanadesikan (2017: 15) notes, [t]here is, in general, significant variation in the basic terminology used in the study of writing systems. Indeed, as Meletis (2018: 73) observes regarding the differences between the concepts of WS and orthography, [t]hese terms are often shockingly misused as synonyms, or writing system is not used at all and orthography is employed instead. Similarly, Joyce and Masuda (in press) seek to differentiate between the elusive trinity of terms at heart of WS research; namely, script, WS, and orthography, with particular reference to the JWS. Opening remarks 2: Our working definitions WS1 [Schrifttyp]: Abstract relations (i.e., morphographic, syllabographic, + phonemic), as focus of typologies. WS2 [Schriftsystem]: Common usage for signs + conventions of given language, such as GWS + JWS. Script [Schrift]: Set of material signs for specific language. Orthography [Orthographie]: Mediation between script + WS, but often with prescriptive connotations of correct writing. Graphematic representation: Emerging from grapholinguistic approach, a neutral (ego preferable) alternative to orthography. GWS: Use of extended alphabetic set, as used to represent written German language. -

Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera U Osijeku Filozofski Fakultet U Osijeku Odsjek Za Engleski Jezik I Književnost Uroš Ba

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet u Osijeku Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Uroš Barjaktarević Japanese-English Language Contact / Japansko-engleski jezični kontakt Diplomski rad Kolegij: Engleski jezik u kontaktu Mentor: doc. dr. sc. Dubravka Vidaković Erdeljić Osijek, 2015. 1 Summary JAPANESE-ENGLISH LANGUAGE CONTACT The paper examines the language contact between Japanese and English. The first section of the paper defines language contact and the most common contact-induced language phenomena with an emphasis on linguistic borrowing as the dominant contact-induced phenomenon. The classification of linguistic borrowing thereby follows Haugen's distinction between morphemic importation and substitution. The second section of the paper presents the features of the Japanese language in terms of origin, phonology, syntax, morphology, and writing. The third section looks at the history of language contact of the Japanese with the Europeans, starting with the Portuguese and Spaniards, followed by the Dutch, and finally the English. The same section examines three different borrowing routes from English, and contact-induced language phenomena other than linguistic borrowing – bilingualism , code alternation, code-switching, negotiation, and language shift – present in Japanese-English language contact to varying degrees. This section also includes a survey of the motivation and reasons for borrowing from English, as well as the attitudes of native Japanese speakers to these borrowings. The fourth and the central section of the paper looks at the phenomenon of linguistic borrowing, its scope and the various adaptations that occur upon morphemic importation on the phonological, morphological, orthographic, semantic and syntactic levels. -

Hiragana and Katakana Worksheets Free

201608 Hiragana and Katakana worksheets ひらがな カタカナ 1. Three types of letters ··········································· 1 _ 2. Roma-ji, Hiragana and Katakana ·························· 2 3. Hiragana worksheets and quizzes ························ 3-9 4. The rules in Hiragana···································· 10-11 5. The rules in Katakana ········································ 12 6. Katakana worksheets and quizzes ··················· 12-22 Japanese Language School, Tokyo, Japan Meguro Language Center TEL.: 03-3493-3727 Email: [email protected] http://www.mlcjapanese.co.jp Meguro Language Center There are three types of letters in Japanese. 1. Hiragana (phonetic sounds) are basically used for particles, words and parts of words. 2. Katakana (phonetic sounds) are basically used for foreign/loan words. 3. Kanji (Chinese characters) are used for the stem of words and convey the meaning as well as sound. Hiragana is basically used to express 46 different sounds used in the Japanese language. We suggest you start learning Hiragana, then Katakana and then Kanji. If you learn Hiragana first, it will be easier to learn Katakana next. Hiragana will help you learn Japanese pronunciation properly, read Japanese beginners' textbooks and write sentences in Japanese. Japanese will become a lot easier to study after having learned Hiragana. Also, as you will be able to write sentences in Japanese, you will be able to write E-mails in Hiragana. Katakana will help you read Japanese menus at restaurants. Hiragana and Katakana will be a good help to your Japanese study and confortable living in Japan. To master Hiragana, it is important to practice writing Hiragana. Revision is also very important - please go over what you have learned several times. -

Hasegawasoliloquych2.Pdf

ne yo Sentence-final particles ne yo ne Yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne yo ne ne yo ne yo Yoku furu ne/yo. Ne yo ne ne yo yo yo ne ne yo yo ne yo Sonna koto wa atarimae da ne/yo. Kimi no imooto-san, uta ga umai ne. ne Kushiro wa samui yo. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne ne Ne Ee, soo desu. Ii tenki da nee. Kyoo wa kinyoobi desu ne. ne Soo desu ne. Yatto isshuukan owarimashita ne. ne ne yo Juubun ja nai desu ka. Watashi to shite wa, mitomeraremasen ne. Chotto yuubinkyoku e itte kimasu ne. Ee, boku wa rikugun no shichootai, ima no yusoobutai da. Ashita wa hareru deshoo nee. shichootai yusoobutai Koshiji-san wa meshiagaru no mo osuki ne. ne affective common ground ne Daisuki. Oshokuji no toki ni mama shikaritaku nai kedo nee. Hitoshi no sono tabekata ni wa moo Denwa desu kedo/yo. ne yo yone Ashita irasshaimasu ka/ne. yo yone ne yo the coordination of dialogue ne Yo ne A soonan desu ka. Soo yo. Ikebe-san wa rikugun nandesu yone. ne yo ne yo ne yo ne Ja, kono zasshi o yonde-miyoo. Yo Kore itsu no zasshi daroo. A, nihon no anime da. procedural encoding anime ne yo A, kono Tooshiba no soojiki shitteru. Hanasu koto ga nakunatchatta. A, jisho wa okutta. Kono hon zuibun furui. Kyoo wa suupaa ni ikanakute ii. ka Kore mo tabemono. wa Dansu kurabu ja nakute shiataa. wa↓ wa wa↑ na Shikakui kuruma-tte suki janai. -

Proper Name Machine Translation from Japanese to Japanese Sign Language

Proper Name Machine Translation from Japanese to Japanese Sign Language Taro Miyazaki, Naoto Kato, Seiki Inoue, Yuji Nagashima Shuichi Umeda, Makiko Azuma, Nobuyuki Hiruma NHK Science & Technology Research Laboratories Faculty of Information, Tokyo, Japan Kogakuin University miyazaki.t-jw, katou.n-ga, inoue.s-li, Tokyo, japan umeda.s-hg,{ azuma.m-ia, hiruma.n-dy @nhk.or.jp [email protected] } Abstract face, and lips. For deaf people, sign language is easier to understand than spoken language because This paper describes machine transla- it is their mother tongue. To convey the meaning tion of proper names from Japanese to of sentences in spoken language to deaf people, Japanese Sign Language (JSL). “Proper the sentences need to be translated into sign lan- name transliteration” is a kind of machine guage. translation of proper names between spo- To provide more information with sign lan- ken languages and involves character-to- guage, we have been studying machine translation character conversion based on pronunci- from Japanese to Japanese Sign Language (JSL). ation. However, transliteration methods As shown in Figure 1, our translation system au- cannot be applied to Japanese-JSL ma- tomatically translates Japanese text into JSL com- chine translation because proper names puter graphics (CG) animations. The system con- in JSL are composed of words rather sists of two major processes: text translation and than characters. Our method involves CG synthesis. Text translation translates word se- not only pronunciation-based translation, quences in Japanese into word sequences in JSL. but also sense-based translation, because CG synthesis generates seamless motion transi- kanji, which are ideograms that compose tions between each sign word motion by using a most Japanese proper names, are closely motion interpolation technique.