Of Writing Systems in Terms of Typological and Other Criteria: Cross-Linguistic Observations from the German and Japanese Writing Systems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ALPHA CHI OMEGA Accreditation Report 2014-2015

ALPHA CHI OMEGA Accreditation Report 2014-2015 Intellectual Development Alpha Chi Omega was ranked second out of nine Panhellenic Sororities in the fall 2014 semester with a GPA of 3.4475, a decrease of .01306 from the spring 2014 semester. The 3.4475 GPA placed the chapter above the All Sorority and All Greek average. Alpha Chi Omega was ranked first out of nine Panhellenic Sororities in the spring 2015 semester with a GPA of 3.48402, an increase of .03652 from the fall 2014 semester. The 3.48402 GPA placed the chapter above the All Sorority and All Greek average. Alpha Chi Omega’s spring 2015 new member class GPA was 3.383, ranking first out of nine Panhellenic Sororities. Alpha Chi Omega had 46.6% of the chapter on the Dean’s List in the fall 2014 semester and 28.2% on the Dean’s List in the spring 2015 semester. Alpha Chi Omega requires a minimum 2.6 GPA for membership. This standard is higher than the Inter/National Headquarters and University requirements. Alpha Chi Omega fosters an environment for strong academic performance. The chapter provides in-house tutoring, peer mentoring, and regular study hours. The chapter also connects members to the Center for Academic Success, the Writing and Math Center, and other on-campus resources. Alpha Chi Omega maintains a designated study space frequently used by members as well as tutors, teaching assistants, and professors leading study sessions. This space is complete with a study buddy desk fully stocked with office and study supplies. Alpha Chi Omega’s academic plan—incorporating individualization and positive incentives—is consistently recognized as a best practice. -

Man'yogana.Pdf (574.0Kb)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO Additional services for Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here The origin of man'yogana John R. BENTLEY Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies / Volume 64 / Issue 01 / February 2001, pp 59 73 DOI: 10.1017/S0041977X01000040, Published online: 18 April 2001 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0041977X01000040 How to cite this article: John R. BENTLEY (2001). The origin of man'yogana. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, 64, pp 5973 doi:10.1017/S0041977X01000040 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/BSO, IP address: 131.156.159.213 on 05 Mar 2013 The origin of man'yo:gana1 . Northern Illinois University 1. Introduction2 The origin of man'yo:gana, the phonetic writing system used by the Japanese who originally had no script, is shrouded in mystery and myth. There is even a tradition that prior to the importation of Chinese script, the Japanese had a native script of their own, known as jindai moji ( , age of the gods script). Christopher Seeley (1991: 3) suggests that by the late thirteenth century, Shoku nihongi, a compilation of various earlier commentaries on Nihon shoki (Japan's first official historical record, 720 ..), circulated the idea that Yamato3 had written script from the age of the gods, a mythical period when the deity Susanoo was believed by the Japanese court to have composed Japan's first poem, and the Sun goddess declared her son would rule the land below. -

Nzila Ye Isa Kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli

NzilaYeIsakwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli Kana Mu I Fumani? ULIMU YA M’ATA OTE ki yena Mubusi wa pupo kamukana. Bupilo bwa luna M bwa cwale ni bwa kwapili bu itingile ku yena. U na ni m’ata a ku fa mupuzonim’ataakufakoto.Unanim’ataakufabupilonim’ataakubu felisa.Haibalutabelwakiyena,likalikalubelahande;haibah’alutabeli,lika ha li na ku lu bela hande. Ki kwa butokwa luli kuli bulapeli bwa luna ibe b’o a amuhela! ˜ Batubalapelakalinzilazenata. Haiba bulapeli bu swana ni nzila, kana Mulimu wa amuhela linzila kaufela za bulapeli? Kutokwa. Jesu, yena mupolofita wa Mulimu, n’a bonisize kuli ku na ni linzila ze peli fela. N’a ize: ˜ “Munyako wa Sinyeho u atami, mi nzila ye ya mwateniiatami,mibabakena ˜ ˜ mwateni ki ba banata. Kakuli munyako wa bupilo wa kumbana, nzila ye ya ˜ mwatenikiyesisani,mikibabanyinyanibabaifumana.”—Mateu7:13,14. ˜ Ku na ni mifuta ye mibeli fela ya bulapeli: bo bunwi bo bu isa kwa ˜ bupilo ni bo bunwibobuisakwasinyeho.Mulelowa broshuwa ye ki ku mi tusa ku fumana nzila ye isa kwa bupilo bo bu sa feli. Mukoloko wa ze Mwahali NzilaYeIsakwa 1 Kana Bulapeli Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli KaufelaBuLutaNiti? ......... 4 2 MuKonakuItuta ˜ Kana Mu I Fumani? CwaniNitikazaMulimu? ..... 5 ˜ 3KiBomani Ba Ba Pila mwaLilukolaMoya? ......... 8 4 Bokukululu ba Luna Ba Kai? . 12 5 NitikazaMabiboniBuloi .... 15 6 Kana Mulimu Wa Amuhela BulapeliKaufela?............ 19 ˜ 7KiBomani Ba Ba Na niBulapelibwaNiti? ........ 22 8 Mu Hane Bulapeli bwa Buhata; Mu Swalisane niBulapelibwaNiti ......... 25 9 Bulapeli bwa Niti Bwa Kona kuMiTusaKuYaKuIle!...... 29 2002 Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania Nzila Ye Isa kwa Bupilo Bo Bu Sa Feli—Kana Mu I Fumani? Bahasanyi Printed by Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of South Africa NPC 1 Robert Broom Drive East, Rangeview, Krugersdorp, 1739, R.S.A. -

SUPPORTING the CHINESE, JAPANESE, and KOREAN LANGUAGES in the OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM by Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT the Asian L

SUPPORTING THE CHINESE, JAPANESE, AND KOREAN LANGUAGES IN THE OPENVMS OPERATING SYSTEM By Michael M. T. Yau ABSTRACT The Asian language versions of the OpenVMS operating system allow Asian-speaking users to interact with the OpenVMS system in their native languages and provide a platform for developing Asian applications. Since the OpenVMS variants must be able to handle multibyte character sets, the requirements for the internal representation, input, and output differ considerably from those for the standard English version. A review of the Japanese, Chinese, and Korean writing systems and character set standards provides the context for a discussion of the features of the Asian OpenVMS variants. The localization approach adopted in developing these Asian variants was shaped by business and engineering constraints; issues related to this approach are presented. INTRODUCTION The OpenVMS operating system was designed in an era when English was the only language supported in computer systems. The Digital Command Language (DCL) commands and utilities, system help and message texts, run-time libraries and system services, and names of system objects such as file names and user names all assume English text encoded in the 7-bit American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) character set. As Digital's business began to expand into markets where common end users are non-English speaking, the requirement for the OpenVMS system to support languages other than English became inevitable. In contrast to the migration to support single-byte, 8-bit European characters, OpenVMS localization efforts to support the Asian languages, namely Japanese, Chinese, and Korean, must deal with a more complex issue, i.e., the handling of multibyte character sets. -

A Ruse Secluded Character Set for the Source

Mukt Shabd Journal Issn No : 2347-3150 A Ruse Secluded character set for the Source Mr. J Purna Prakash1, Assistant Professor Mr. M. Rama Raju 2, Assistant Professor Christu Jyothi Institute of Technology & Science Abstract We are rich in data, but information is poor, typically world wide web and data streams. The effective and efficient analysis of data in which is different forms becomes a challenging task. Searching for knowledge to match the exact keyword is big task in Internet such as search engine. Now a days using Unicode Transform Format (UTF) is extended to UTF-16 and UTF-32. With helps to create more special characters how we want. China has GB 18030-character set. Less number of website are using ASCII format in china, recently. While searching some keyword we are unable get the exact webpage in search engine in top place. Issues in certain we face this problem in results announcement, notifications, latest news, latest products released. Mainly on government websites are not shown in the front page. To avoid this trap from common people, we require special character set to match the exact unique keyword. Most of the keywords are encoded with the ASCII format. While searching keyword called cbse net results thousands of websites will have the common keyword as cbse net results. Matching the keyword, it is already encoded in all website as ASCII format. Most of the government websites will not offer search engine optimization. Match a unique keyword in government, banking, Institutes, Online exam purpose. Proposals is to create a character set from A to Z and a to z, for the purpose of data cleaning. -

Kiraz 2019 a Functional Approach to Garshunography

Intellectual History of the Islamicate World 7 (2019) 264–277 brill.com/ihiw A Functional Approach to Garshunography A Case Study of Syro-X and X-Syriac Writing Systems George A. Kiraz Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton and Beth Mardutho: The Syriac Institute, Piscataway [email protected] Abstract It is argued here that functionalism lies at the heart of garshunographic writing systems (where one language is written in a script that is sociolinguistically associated with another language). Giving historical accounts of such systems that began as early as the eighth century, it will be demonstrated that garshunographic systems grew organ- ically because of necessity and that they offered a certain degree of simplicity rather than complexity.While the paper discusses mostly Syriac-based systems, its arguments can probably be expanded to other garshunographic systems. Keywords Garshuni – garshunography – allography – writing systems It has long been suggested that cultural identity may have been the cause for the emergence of Garshuni systems. (In the strictest sense of the term, ‘Garshuni’ refers to Arabic texts written in the Syriac script but the term’s semantics were drastically extended to other systems, sometimes ones that have little to do with Syriac—for which see below.) This paper argues for an alterna- tive origin, one that is rooted in functional theory. At its most fundamental level, Garshuni—as a system—is nothing but a tool and as such it ought to be understood with respect to the function it performs. To achieve this, one must take into consideration the social contexts—plural, as there are many—under which each Garshuni system appeared. -

The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing Writing Systems Using Orthography Profiles

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Moran, Steven ; Cysouw, Michael DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-135400 Monograph The following work is licensed under a Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License. Originally published at: Moran, Steven; Cysouw, Michael (2017). The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists: Managing writing systems using orthography profiles. CERN Data Centre: Zenodo. DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.290662 The Unicode Cookbook for Linguists Managing writing systems using orthography profiles Steven Moran & Michael Cysouw Change dedication in localmetadata.tex Preface This text is meant as a practical guide for linguists, and programmers, whowork with data in multilingual computational environments. We introduce the basic concepts needed to understand how writing systems and character encodings function, and how they work together. The intersection of the Unicode Standard and the International Phonetic Al- phabet is often not met without frustration by users. Nevertheless, thetwo standards have provided language researchers with a consistent computational architecture needed to process, publish and analyze data from many different languages. We bring to light common, but not always transparent, pitfalls that researchers face when working with Unicode and IPA. Our research uses quantitative methods to compare languages and uncover and clarify their phylogenetic relations. However, the majority of lexical data available from the world’s languages is in author- or document-specific orthogra- phies. -

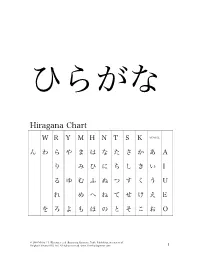

Hiragana Chart

ひらがな Hiragana Chart W R Y M H N T S K VOWEL ん わ ら や ま は な た さ か あ A り み ひ に ち し き い I る ゆ む ふ ぬ つ す く う U れ め へ ね て せ け え E を ろ よ も ほ の と そ こ お O © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 1 Beginning Japanese 名前: ________________________ 1-1 Hiragana Activity Book 日付: ___月 ___日 一、 Practice: あいうえお かきくけこ がぎぐげご O E U I A お え う い あ あ お え う い あ お う あ え い あ お え う い お う い あ お え あ KO KE KU KI KA こ け く き か か こ け く き か こ け く く き か か こ き き か こ こ け か け く く き き こ け か © 2010 Michael L. Kluemper et al. Beginning Japanese, Tuttle Publishing, an imprint of Periplus Editions (HK) Ltd. All rights reserved. www.TimeForJapanese.com. 2 GO GE GU GI GA ご げ ぐ ぎ が が ご げ ぐ ぎ が ご ご げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ が が ご げ ぎ が ご ご げ が げ ぐ ぐ ぎ ぎ ご げ が 二、 Fill in each blank with the correct HIRAGANA. SE N SE I KI A RA NA MA E 1. -

Handy Katakana Workbook.Pdf

First Edition HANDY KATAKANA WORKBOOK An Introduction to Japanese Writing: KANA THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT FOR BEGINNING LEVEL JAPANESE LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION. \ FrF!' '---~---- , - Y. M. Shimazu, Ed.D. -----~---- TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENlS vii STUDYSHEET#l 1 A,I,U,E, 0, KA,I<I, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #1 2 PRACTICE: A, I,U, E, 0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU, GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #2 3 MORE PRACTICE: A, I, U, E,0, KA,KI,KU, KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N WORKSHEET #~3 4 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: A,I,U, E,0, KA,KI, KU,KE, KO, GA,GI,GU,GE,GO, N STUDYSHEET #2 5 SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI,ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #4 6 PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI, 'lSU,TE,TO, OA, DE,DO WORI<SHEEI' #5 7 MORE PRACTICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE,SO, ZA,II, ZU,ZE, W, TA, CHI, TSU, TE,TO, DA, DE,DO WORKSHEET #6 8 ADDmONAL PRACI'ICE: SA,SHI,SU,SE, SO, ZA,JI, ZU,ZE,ZO, TA, CHI,TSU,TE,TO, DA, DE,DO STUDYSHEET #3 9 NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE, HO, BA, BI,BU,BE,BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #7 10 PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI,FU,HE,HO, BA,BI, BU,BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #8 11 MORE PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU,NE,NO, HA,HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,BU,BE, BO, PA,PI,PU,PE,PO WORKSHEET #9 12 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: NA,NI, NU, NE,NO, HA, HI, FU,HE, HO, BA,BI,3U, BE, BO, PA, PI,PU,PE,PO STUDYSHEET #4 13 MA, MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET#10 14 PRACTICE: MA,MI, MU,ME, MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #11 15 MORE PRACTICE: MA, MI,MU,ME,MO, YA, W, YO WORKSHEET #12 16 ADDmONAL PRACTICE: MA,MI,MU, ME, MO, YA, W, YO STUDYSHEET #5 17 -

Na Kana Magiti Kei Na Lotu

1 NA KANA MAGITI KEI NA LOTU (Vola Tabu : Maciu 22:1-10; Luke 14:12-24) Vola ko Rev. Dr. Ilaitia S. Tuwere. Sa inaki ni vunau oqo me taroga ka sauma talega na taro : A cava na Lotu? Ni da tekivu edaidai ena noda solevu vakalotu, sa na yaga meda taroga ka tovolea talega me sauma na taro oqori. Ia, ena levu na kena isau eda na solia, me vaka na: gumatuataki ni masu kei na vulici ni Vola Tabu, bula vakayalo, muria na ivakarau se lawa ni lotu ka vuqa tale. Na veika oqori era ka dina ka tu kina eso na isau ni taro : A Cava na Lotu. Na i Vola Tabu e sega ni tuvalaka vakavosa vei keda na ibalebale ni lotu. E vakavuqa me boroya vei keda na iyaloyalo me vakadewataka kina na veika eso e vinakata me tukuna. E sega talega ni solia e duabulu ga na iyaloyalo me baleta na lotu. E vuqa sara e solia vei keda. Oqori me vaka na Qele ni Sipi kei na i Vakatawa Vinaka; na Vuni Vaini kei na Tabana; na i Vakavuvuli kei iratou na nona Gonevuli se Tisaipeli, na Masima se Rarama kei Vuravura, na Ulu kei na Vo ni Yago taucoko, ka vuqa tale. Ena mataka edaidai, meda raica vata yani na iyaloyalo ni kana magiti. E rua na kena ivakamacala eda rogoca, mai na Kosipeli i Maciu kei na nei Luke. Na kana magiti se na solevu edua na ivakarau vakaitaukei. Eda soqoni vata kina vakaveiwekani ena noda veikidavaki kei na marau, kena veitalanoa, kena sere kei na meke, kena salusalu kei na kumuni iyau. -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion

Implementing Cross-Locale CJKV Code Conversion Ken Lunde CJKV Type Development Adobe Systems Incorporated bc ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-paper.pdf ftp://ftp.oreilly.com/pub/examples/nutshell/ujip/unicode/iuc13-c2-slides.pdf Code Conversion Basics dc • Algorithmic code conversion — Within a single locale: Shift-JIS, EUC-JP, and ISO-2022-JP — A purely mathematical process • Table-driven code conversion — Required across locales: Chinese ↔ Japanese — Required when dealing with Unicode — Mapping tables are required — Can sometimes be faster than algorithmic code conversion— depends on the implementation September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Code Conversion Basics (Cont’d) dc • CJKV character set differences — Different number of characters — Different ordering of characters — Different characters September 10, 1998 Copyright © 1998 Adobe Systems Incorporated Character Sets Versus Encodings dc • Common CJKV character set standards — China: GB 1988-89, GB 2312-80; GB 1988-89, GBK — Taiwan: ASCII, Big Five; CNS 5205-1989, CNS 11643-1992 — Hong Kong: ASCII, Big Five with Hong Kong extension — Japan: JIS X 0201-1997, JIS X 0208:1997, JIS X 0212-1990 — South Korea: KS X 1003:1993, KS X 1001:1992, KS X 1002:1991 — North Korea: ASCII (?), KPS 9566-97 — Vietnam: TCVN 5712:1993, TCVN 5773:1993, TCVN 6056:1995 • Common CJKV encodings — Locale-independent: EUC-*, ISO-2022-* — Locale-specific: GBK, Big Five, Big Five Plus, Shift-JIS, Johab, Unified Hangul Code — Other: UCS-2, UCS-4, UTF-7, UTF-8,