The Art and Artists of Hong Kong

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booxter Export Page 1

Cover Title Authors Edition Volume Genre Format ISBN Keywords The Museum of Found Mirjam, LINSCHOOTEN Exhibition Soft cover 9780968546819 Objects: Toronto (ed.), Sameer, FAROOQ Catalogue (Maharaja and - ) (ed.), Haema, SIVANESAN (Da bao)(Takeout) Anik, GLAUDE (ed.), Meg, Exhibition Soft cover 9780973589689 Chinese, TAYLOR (ed.), Ruth, Catalogue Canadian art, GASKILL (ed.), Jing Yuan, multimedia, 21st HUANG (trans.), Xiao, century, Ontario, OUYANG (trans.), Mark, Markham TIMMINGS Piercing Brightness Shezad, DAWOOD. (ill.), Exhibition Hard 9783863351465 film Gerrie, van NOORD. (ed.), Catalogue cover Malenie, POCOCK (ed.), Abake 52nd International Art Ming-Liang, TSAI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover film, mixed Exhibition - La Biennale Huang-Chen, TANG (ill.), Catalogue media, print, di Venezia - Atopia Kuo Min, LEE (ill.), Shih performance art Chieh, HUANG (ill.), VIVA (ill.), Hongjohn, LIN (ed.) Passage Osvaldo, YERO (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover 9780978241995 Sculpture, mixed Charo, NEVILLE (ed.), Catalogue media, ceramic, Scott, WATSON (ed.) Installaion China International Arata, ISOZAKI (ill.), Exhibition Soft cover architecture, Practical Exhibition of Jiakun, LIU (ill.), Jiang, XU Catalogue design, China Architecture (ill.), Xiaoshan, LI (ill.), Steven, HOLL (ill.), Kai, ZHOU (ill.), Mathias, KLOTZ (ill.), Qingyun, MA (ill.), Hrvoje, NJIRIC (ill.), Kazuyo, SEJIMA (ill.), Ryue, NISHIZAWA (ill.), David, ADJAYE (ill.), Ettore, SOTTSASS (ill.), Lei, ZHANG (ill.), Luis M. MANSILLA (ill.), Sean, GODSELL (ill.), Gabor, BACHMAN (ill.), Yung -

General Interest

GENERAL INTEREST GeneralInterest 4 FALL HIGHLIGHTS Art 60 ArtHistory 66 Art 72 Photography 88 Writings&GroupExhibitions 104 Architecture&Design 116 Journals&Annuals 124 MORE NEW BOOKS ON ART & CULTURE Art 130 Writings&GroupExhibitions 153 Photography 160 Architecture&Design 168 Catalogue Editor Thomas Evans Art Direction Stacy Wakefield Forte Image Production BacklistHighlights 170 Nicole Lee Index 175 Data Production Alexa Forosty Copy Writing Cameron Shaw Printing R.R. Donnelley Front cover image: Marcel Broodthaers,“Picture Alphabet,” used as material for the projection “ABC-ABC Image” (1974). Photo: Philippe De Gobert. From Marcel Broodthaers: Works and Collected Writings, published by Poligrafa. See page 62. Back cover image: Allan McCollum,“Visible Markers,” 1997–2002. Photo © Andrea Hopf. From Allan McCollum, published by JRP|Ringier. See page 84. Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, “TP 35.” See Toilet Paper issue 2, page 127. GENERAL INTEREST THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART,NEW YORK De Kooning: A Retrospective Edited and with text by John Elderfield. Text by Jim Coddington, Jennifer Field, Delphine Huisinga, Susan Lake. Published in conjunction with the first large-scale, multi-medium, posthumous retrospective of Willem de Kooning’s career, this publication offers an unparalleled opportunity to appreciate the development of the artist’s work as it unfolded over nearly seven decades, beginning with his early academic works, made in Holland before he moved to the United States in 1926, and concluding with his final, sparely abstract paintings of the late 1980s. The volume presents approximately 200 paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints, covering the full diversity of de Kooning’s art and placing his many masterpieces in the context of a complex and fascinating pictorial practice. -

Frog King: Totem: an Evolution

Valerie C. Doran Frog King: Totem: An Evolution n inimitable force unto himself, Frog King (a.k.a. Kwok Mang Ho) is a pioneering conceptual and performance artist who A has been breaking boundaries in Hong Kong and beyond since the late 1960s. Frog King’s artistic awareness is marked by a deeply integrated hybridity derived from dual roots based in two very different aesthetic-philosophical systems. One root draws from elements of Chinese cosmological philosophy that underlie all Chinese traditional art forms, in particular the connective mutability of the five elements of water, earth, fire, metal, and wood. In different manifestations these elements and their transmutations are present physically throughout Frog King’s work. The other root draws from the contemporary “art is life” philosophy of influential artists like Alan Kaprow and Fluxus artist Naim Jun Paik, early exponents of the happening and of the dissolution of the divide between artist and audience/art and daily life. In Frog King, the creative and philosophical DNA of these seemingly disparate and even incongruous sources of influence have mutated into a being of enormous creative vitality and a kind of all-embracing, life-affirming anarchy. Left: Korean video artist Nam Jun Paik wearing "froggie sunglasses" for One Second Live Body Performance, 1994, New York City. Right: Mother and son wearing "froggie sunglasses" for One Second Live Body Performance, À}Ì«>ÊUÊ Hongkornucopia, Venice Biennale, 2011. Courtesy of the artist. This quality of hybridity is represented in the amphibious nature of the frog and captured in Frog King’s seal or emblem of the abstracted frog face, whose two triangular eyes also imply a bridge or a pair of sails as symbols of connectivity. -

Branch List English

Telephone Name of Branch Address Fax No. No. Central District Branch 2A Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2160 8888 2545 0950 Des Voeux Road West Branch 111-119 Des Voeux Road West, Hong Kong 2546 1134 2549 5068 Shek Tong Tsui Branch 534 Queen's Road West, Shek Tong Tsui, Hong Kong 2819 7277 2855 0240 Happy Valley Branch 11 King Kwong Street, Happy Valley, Hong Kong 2838 6668 2573 3662 Connaught Road Central Branch 13-14 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2841 0410 2525 8756 409 Hennessy Road Branch 409-415 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2835 6118 2591 6168 Sheung Wan Branch 252 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2541 1601 2545 4896 Wan Chai (China Overseas Building) Branch 139 Hennessy Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2529 0866 2866 1550 Johnston Road Branch 152-158 Johnston Road, Wan Chai, Hong Kong 2574 8257 2838 4039 Gilman Street Branch 136 Des Voeux Road Central, Hong Kong 2135 1123 2544 8013 Wyndham Street Branch 1-3 Wyndham Street, Central, Hong Kong 2843 2888 2521 1339 Queen’s Road Central Branch 81-83 Queen’s Road Central, Hong Kong 2588 1288 2598 1081 First Street Branch 55A First Street, Sai Ying Pun, Hong Kong 2517 3399 2517 3366 United Centre Branch Shop 1021, United Centre, 95 Queensway, Hong Kong 2861 1889 2861 0828 Shun Tak Centre Branch Shop 225, 2/F, Shun Tak Centre, 200 Connaught Road Central, Hong Kong 2291 6081 2291 6306 Causeway Bay Branch 18 Percival Street, Causeway Bay, Hong Kong 2572 4273 2573 1233 Bank of China Tower Branch 1 Garden Road, Hong Kong 2826 6888 2804 6370 Harbour Road Branch Shop 4, G/F, Causeway Centre, -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Sep-2018

WWF - DDC Location Plan Sep-2018 Mon Tue Wed Thu Fri Sat Sun 1 2 Team A King Man Street, Sai Kung (Near Sai Kung Library) Day-Off Team B Chong Yip Shopping Centre Chong Yip Shopping Centre Team C Quarry Bay MTR Station Exit B Bridge Quarry Bay MTR Station Exit B Bridge Team D Tsim Sha Tsui East (Near footbridge) Tsim Sha Tsui East (Near footbridge) Team E Citic Tower, Admiralty (Near footbridge) Citic Tower, Admiralty (Near footbridge) Team F Wanchai Sports Centre (Near footbridge) Wanchai Sports Centre (Near footbridge) Team G Kwai Hing MTR Station (Near footbridge) Kwai Hing MTR Station (Near footbridge) Team H Mong Kok East MTR Station Mong Kok East MTR Station Team I V City, Tuen Mun V City, Tuen Mun Team J Ngau Tau Kok MTR Exit B (Near tunnel) Ngau Tau Kok MTR Exit B (Near tunnel) Team K Kwun Chung Sports Centre Kwun Chung Sports Centre Team L Tai Yau Building, Wan Chai Tai Yau Building, Wan Chai Team M Hiu Kwong Street Sports Centre, Kwun Tong Hiu Kwong Street Sports Centre, Kwun Tong Team N Tiu Keng Leng MTR Station Exit B Tiu Keng Leng MTR Station Exit B Team O Lockhart Road Public Library, Wan Chai Lockhart Road Public Library, Wan Chai Team P Leighton Centre, Causeway Bay Leighton Centre, Causeway Bay Team Q AIA Tower, Fortress Hill AIA Tower, Fortress Hill Team R Chai Wan Sports Centre Front door Chai Wan Sports Centre Front door Team S 21 Shan Mei Street, Fo Tan 21 Shan Mei Street, Fo Tan 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Cheung Sha Wan Road (near Cheung Sha Wan Tsing Hoi Circuit, Tuen Mun Team A Russell Street, Causeway Bay Castle Peak Road, -

L/St68/4 L/St66/1 L/St72/1 L/St41a/1A L/St14b/3 L/St7/1B L

TAI PO KAU CENTRE ISLAND New Village fi”· U¤J |ÅA» Seaview ( A CHAU ) Emerald Palace Ha Wun Yiu Villas Qflt flK W⁄¶ EAST RAIL LINE Wu Kwai Sha Tsui J¸ Lai Chi Shan Pottery Kilns …P Sheung Wong Yi Au FªK W¤J Fan Sin Temple t 100 ‹pfi Ser Res Sheung Wun Yiu j¤H®] “‚” 100 The Paramount Golf Course Tai Po Kau B»A» ” Lo Wai i±Î Savanna Garden Constellation Cove j¤H®] «‰fi ¥¥ Cheung Uk Tei s·Î s¤ Tai Po Kau Villa Costa JC Castle San Wai Whitehead 200 San Uk Ka 282 t Headland flK Ser Res · L/ST111/4 Lai Chi Hang ⁄Ɖ 65 200 s·A» To Tau Providence Bay 300 Villa Castell QªJ WU KAI SHA Tsung Tsai Yuen 100 ‡fl L/ST110/3 400 s¤»³ b¥s DeerHill Bay Hilltop Garden Pun Shan Chau “ dª Double Cove «^ 200 øª è¦ Nai Chung ¼¿ Cheung SAI SHA ROAD Symphony Bay TOLO HIGHWAY Q¯Ë Sai O 500 Tsiu Hang Kang C Q¯Ë· Wu Kai Sha 100 300 ' L/ST100/3 A` Q¯Ë·F¨C Wu Kai Sha ¨»·E … Pumping x© Lookout Wu Kwai Sha Village Lake Silver Station Kwun Hang Ø¿⁄ 408 aª Youth Village Cheung Muk Tau … ¥ Sw P ¤bs fi A» Cheung Shue Pak Shek Kok Ma On Shan o´ ¸¤[ Villa Oceania Monte Vista Water Treatment fi Tan Park As »›· Villa Athena fi¶ Yuen Tun Ha ƒB Kon Hang Kam Lung Q§w 100 Works Hong Kong Science Park fił Lo Lau Uk Bayshore Towers Court Lee On Pipeline 300 ¶d Estate Water Tunnel “ I´_Ä Wong Nai Fai Marbella ¤b Saddle Ridge Ma On Shan Garden t P¿ |¹w s• Ser Res Yin Ngam Y© A Sunshine City ´¥K Po Min A^ L/ST108/2 400 Ta Tit Yan 438 MA LIU SHUI Ʊ 200 j⁄Hfi]ƒM@¯z† 100 Chung On ¤b Kam Ying Pai Mun Kam Fung 200 300 Estate Court Court t TAI PO KAU NATURE RESERVE j¤H MA ON SHAN Ser Res 500 Tai Po -

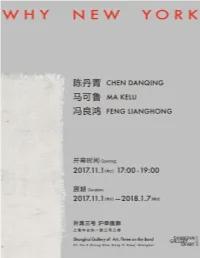

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

Missing the Trend. Hong Kong As a Latecomer in Creativity-Led Urban Development

Corso di Laurea magistrale Lingue e Istituzioni Economiche e Giuridiche dell'Asia e dell'Africa Mediterranea Tesi di Laurea Missing the trend. Hong Kong as a latecomer in creativity-led urban development. Cultural and Creative Industries (CCI) in Hong Kong. Relatore Prof. Fabrizio Panozzo Laureando Benedetta Tavecchia Matricola 987023 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 1 To Maria Giulia 2 I am enormously grateful to my Family for supporting me, to my thesis supervisor Fabrizio Panozzo for the great opportunity which was offered to me and to a number of people who supported my research in Shenzhen, China. I am particularly thankful to Xiaodu Liu, Yan Meng, Tat Lam, Travis Bunt, Jason, Camilla Costa, Anna Laura Govoni for inspiring me during many discussion in the office. My work has greatly benefited from the collaboration with all Urban Research Bureau staff that I would like to thank for their encouragement, this thesis would not have happened without your help in translations, interviews, graphics and materials. A special thanks goes to my family and friends, thank you for being able to stay close despite many years spent travelling: Gianluca, Silvana, Giulia, Federica, Maria Luisa, Stefania, Claudia, Roberto, Paolo, Kikki and Fiammetta. Thank you very much Judith for the great life lesson you gave me and also for giving me children's classrooms to study during summer nights spent at Caef. Finally, a special thank to my sister Maria Giulia for being an incomparable sister and also best friend and mother. A better sister I could not have deserve. I dedicate this degree to my family, from this moment I start my own life. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center Presents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center presents Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974-1985 On view at Asia Society Gallery (Former Magazine A) May 15 - September 1, 2013 (Hong Kong, May 13, 2013) Asia Society Hong Kong Center today announced that Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974 – 1985, will be unveiled to audiences at Asia Society Hong Kong Center from May 15-September 1. The exhibition offers a revealing look into the spectrum of work created by three of China’s most influential contemporary art groups: Wuming (No Name), Xingxing (Stars), and Caocao (Grass Society). Light Before Dawn presents the works of twenty-two artists from the three art groups of Wuming, Xingxing and Caocao, emerged from the Cultural Revolution, who sought artistic truth in the authenticity of human desire, pain and dreams, explored the personal meaning of creativity, and asserted the value of the individuals. Crossing the boundaries of subject matter and style, they questioned, re-evaluated and redefined the forms, the nature of beauty and the art of China. Distinctive in their art approaches, the Wuming group retained an interest in representations of nature, the Xingxing group explored historically Western modes of modernism, absorbing anew, progressive styles developed in Europe and America during the early twentieth century, including surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism while the Caocao group, trained in the native medium of ink and color on paper, attempted to shed both the legacy of socialist realism and the burdens of tradition by turning to new forms of abstract ink painting. Although each movement took a distinctly different artistic approach, they were united in their commitment to pushing Chinese art beyond the borders of Socialist Realism. -

Nameless Art in the Mao Era

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Nameless Art in the Mao Era Tianchu Gao College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Gao, Tianchu, "Nameless Art in the Mao Era" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1091. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1091 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nameless Art in the Mao Era A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Department of Art and Art History from The College of William and Mary by Tianchu (Jane) Gao 高天楚 Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, Non-Honors) ________________________________________ Xin Wu, Director ________________________________________ Sibel Zandi-Sayek ________________________________________ Charles Palermo ________________________________________ Michael Gibbs Hill Williamsburg, VA May 2, 2017 ABSTRACT This research project focuses on the first generation of No Name (wuming 無名), an underground art group in the Cultural Revolution which secretly practiced art countering the official Socialist Realism because of its non-realist visual language and art-for-art’s-sake philosophy. These artists took advantage of their worker status to learn and practice art legitimately in the Mass Art System of the time. They developed their particular style and vision of art from their amateur art training, forbidden visual and textual sources in the underground cultural sphere, and official theoretical debates on art. -

“China” on Display for European Audiences? the Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993)

66 “China” on Display for European Audiences? “China” on Display for European Audiences? The Making of an Early Travelling Exhibition of Contemporary Chinese Art–China Avantgarde (Berlin/1993) Franziska Koch, Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Contemporary Chinese Art–Phenomenon and Discursive Category Mediated by Exhibitions Exhibitions have always been at the heart of the modern art world and its latest developments. They are contested sites where the joint forces of art objects, their social agents, and institutional spaces intersect temporarily and provide a visual arrangement for specific audiences, whose interpretations themselves feed back into the discourse on art. Viewed from this perspective, contemporary Chinese art–as a phenomenon and as a discursive category that refer to specific dimensions of artistic production in post-1979 China– was mediated through various exhibitions that took place in the People’s Republic of China (hereafter, People’s Republic). In 1989, art from the People’s Republic also began to appear in European and North American exhibitions significantly expanding Western knowledge of this artistic production. Since then, national and international exhibitions have multiplied, while simultaneously becoming increasingly entangled: the sheer number of artworks that circulate between Chinese urban art scenes and Western art metropolises has risen steeply, as have the often overlapping circles of contemporary artists, art critics, art historians, gallery owners, and collectors who successfully engage across both sides of the field. To a certain degree these agents govern exhibition-making and act as important mediators or “cultural brokers”1 globalizing the discursive category of contemporary 1 For a recent study that explores the notion of the “cultural broker” from a transcultural perspective see Rudolf G.