Popular Memories of the Mao Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide

08 Investment.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 14/9/16 12:21 pm Page 81 Week in China China’s Tycoons Investment Lu Zhiqiang China Oceanwide Oceanwide Holdings, its Shenzhen-listed property unit, had a total asset value of Rmb118 billion in 2015. Hurun’s China Rich List He is the key ranked Lu as China’s 8th richest man in 2015 investor behind with a net worth of Rmb83 billlion. Minsheng Bank and Legend Guanxi Holdings A long-term ally of Liu Chuanzhi, who is known as the ‘godfather of Chinese entrepreneurs’, Oceanwide acquired a 29% stake in Legend Holdings (the parent firm of Lenovo) in 2009 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences for Rmb2.7 billion. The transaction was symbolic as it marked the dismantling of Legend’s SOE status. Lu and Liu also collaborated to establish the exclusive Taishan Club in 1993, an unofficial association of entrepreneurs named after the most famous mountain in Shandong. Born in Shandong province in 1951, Lu In fact, according to NetEase Finance, it was graduated from the elite Shanghai university during the Taishan Club’s inaugural meeting – Fudan. His first job was as a technician with hosted by Lu in Shandong – that the idea of the Shandong Weifang Diesel Engine Factory. setting up a non-SOE bank was hatched and the proposal was thereafter sent to Zhu Getting started Rongji. The result was the establishment of Lu left the state sector to become an China Minsheng Bank in 1996. entrepreneur and set up China Oceanwide. Initially it focused on education and training, Minsheng takeover? but when the government initiated housing Oceanwide was one of the 59 private sector reform in 1988, Lu moved into real estate. -

WIC Template 13/9/16 11:52 Am Page IFC1

In a little over 35 years China’s economy has been transformed Week in China from an inefficient backwater to the second largest in the world. If you want to understand how that happened, you need to understand the people who helped reshape the Chinese business landscape. china’s tycoons China’s Tycoons is a book about highly successful Chinese profiles of entrepreneurs. In 150 easy-to- digest profiles, we tell their stories: where they came from, how they started, the big break that earned them their first millions, and why they came to dominate their industries and make billions. These are tales of entrepreneurship, risk-taking and hard work that differ greatly from anything you’ll top business have read before. 150 leaders fourth Edition Week in China “THIS IS STILL THE ASIAN CENTURY AND CHINA IS STILL THE KEY PLAYER.” Peter Wong – Deputy Chairman and Chief Executive, Asia-Pacific, HSBC Does your bank really understand China Growth? With over 150 years of on-the-ground experience, HSBC has the depth of knowledge and expertise to help your business realise the opportunity. Tap into China’s potential at www.hsbc.com/rmb Issued by HSBC Holdings plc. Cyan 611469_6006571 HSBC 280.00 x 170.00 mm Magenta Yellow HSBC RMB Press Ads 280.00 x 170.00 mm Black xpath_unresolved Tom Fryer 16/06/2016 18:41 [email protected] ${Market} ${Revision Number} 0 Title Page.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 6:36 pm Page 1 china’s tycoons profiles of 150top business leaders fourth Edition Week in China 0 Welcome Note.FIN.qxp_Layout 1 13/9/16 3:10 pm Page 2 Week in China China’s Tycoons Foreword By Stuart Gulliver, Group Chief Executive, HSBC Holdings alking around the streets of Chengdu on a balmy evening in the mid-1980s, it quickly became apparent that the people of this city had an energy and drive Wthat jarred with the West’s perception of work and life in China. -

Andreas Schmid Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT ANDREAS SCHMID Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise, Anthony Yung Date: 27 Apr 2008 Duration: about 2 hours Location: Asia Art Archive, Hong Kong Question (Q): Why did you go to China? Where you and what were you doing? Who are some of the artists that you encountered and what do you think about them? What were the artists reading and what are your comments on those materials? Andreas Schmid (AS): I graduated from the Art Academy in Stuttgart in 1981, studying painting. My paintings were, at that time, very different from German painters like Kiefer in that they always have free space, and transparency of layers of space in them. I painted with oil and acrylic, and it was different from my colleagues/contemporaries. I became interested in the idea of space, of Chinese Art, classical Chinese art, like Ni Zan [倪赞] in the fourteenth century. Then I went to Cologne and saw a collection of Japanese Buddhist writings collected by Seiko Kono , abbot of the Daian-ji temple in Nara City , Japan. I would like to know the line from another side, because lines played the most important role graphically in my paintings. So I tried contacting organizations that would support me, and they informed me there was only one woman who went to China as an artist from Germany with the support of the German exchange service. I went to see her, and she had studied in Hangzhou one year ago at that time (1980). She studied birds and flowers painting. She told me, if you want to do this, you should go to China, it is interesting. -

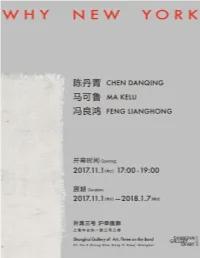

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center Presents

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Asia Society Hong Kong Center presents Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974-1985 On view at Asia Society Gallery (Former Magazine A) May 15 - September 1, 2013 (Hong Kong, May 13, 2013) Asia Society Hong Kong Center today announced that Light Before Dawn: Unofficial Chinese Art 1974 – 1985, will be unveiled to audiences at Asia Society Hong Kong Center from May 15-September 1. The exhibition offers a revealing look into the spectrum of work created by three of China’s most influential contemporary art groups: Wuming (No Name), Xingxing (Stars), and Caocao (Grass Society). Light Before Dawn presents the works of twenty-two artists from the three art groups of Wuming, Xingxing and Caocao, emerged from the Cultural Revolution, who sought artistic truth in the authenticity of human desire, pain and dreams, explored the personal meaning of creativity, and asserted the value of the individuals. Crossing the boundaries of subject matter and style, they questioned, re-evaluated and redefined the forms, the nature of beauty and the art of China. Distinctive in their art approaches, the Wuming group retained an interest in representations of nature, the Xingxing group explored historically Western modes of modernism, absorbing anew, progressive styles developed in Europe and America during the early twentieth century, including surrealism, cubism, and abstract expressionism while the Caocao group, trained in the native medium of ink and color on paper, attempted to shed both the legacy of socialist realism and the burdens of tradition by turning to new forms of abstract ink painting. Although each movement took a distinctly different artistic approach, they were united in their commitment to pushing Chinese art beyond the borders of Socialist Realism. -

The Arts of Making Do and Working out in Beijing, China

What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Michelle Yang Zhang All Rights Reserved Abstract What are friends for?: The arts of making do and working out in Beijing, China Michelle Yang Zhang Through a second look at the now twenty-five-year-old literature on guanxi, a form of reciprocal relationship making and using in China, I examine how the kinds of opportunities and challenges possible for young people intersect with who they know and how this has changed (with its own set of reflections on and consequences for a still-rapidly changing China) since China’s rural to urban transition. My dissertation project examines how young people in contemporary urban China form and produce guanxi ties (resource-full relationships) through the theoretical lens of practice and possibility, inspired by de Certeau’s conceptualization of practice, productive consumption, and strategies versus tactics (1984). Drawing on qualitative data gathered through participant observation and unstructured interviews, I sought to both describe and analyze when, where, and how social networks became consequential. Central to my methodology is an emphasis on people and their practices rather than the common sense categories used to describe them. The people in my field research were predominantly aged 18- 30 and came from a range of ethnic, professional, and education backgrounds. In so doing, I was able to examine the moments and contexts within which some people have opportunities and others do not, as well as when some are vulnerable while others are less so. -

From" Morning Sun" To" Though I Was Dead": the Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident"

From" Morning Sun" to" Though I Was Dead": The Image of Song Binbin in the "August Fifth Incident" Wei-li Wu, Taipei College of Maritime Technology, Taiwan The Asian Conference on Film & Documentary 2016 Official Conference Proceedings Abstract This year is the fiftieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. On August 5, 1966, Bian Zhongyun, the deputy principal at the girls High School Attached to Beijing Normal University, was beaten to death by the students struggling against her. She was the first teacher killed in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and her death had established the “violence” nature of the Cultural Revolution. After the Cultural Revolution, the reminiscences, papers, and comments related to the “August Fifth Incident” were gradually introduced, but with all blames pointing to the student leader of that school, Song Binbin – the one who had pinned a red band on Mao Zedong's arm. It was not until 2003 when the American director, Carma Hinton filmed the Morning Sun that Song Binbin broke her silence to defend herself. However, voices of attacks came hot on the heels of her defense. In 2006, in Though I Am Gone, a documentary filmed by the Chinese director Hu Jie, the responsibility was once again laid on Song Binbin through the use of images. Due to the differences in perception between the two sides, this paper subjects these two documentaries to textual analysis, supplementing it with relevant literature and other information, to objectively outline the two different images of Song Binbin in the “August Fifth Incident” as perceived by people and their justice. -

The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan

THE HISTORY OF GYALTHANG UNDER CHINESE RULE: MEMORY, IDENTITY, AND CONTESTED CONTROL IN A TIBETAN REGION OF NORTHWEST YUNNAN Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Michael Tsin Michelle T. King Ralph A. Litzinger W. Miles Fletcher Donald M. Reid © 2016 Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii! ! ABSTRACT Dá!a Pejchar Mortensen: The History of Gyalthang Under Chinese Rule: Memory, Identity, and Contested Control in a Tibetan Region of Northwest Yunnan (Under the direction of Michael Tsin) This dissertation analyzes how the Chinese Communist Party attempted to politically, economically, and culturally integrate Gyalthang (Zhongdian/Shangri-la), a predominately ethnically Tibetan county in Yunnan Province, into the People’s Republic of China. Drawing from county and prefectural gazetteers, unpublished Party histories of the area, and interviews conducted with Gyalthang residents, this study argues that Tibetans participated in Communist Party campaigns in Gyalthang in the 1950s and 1960s for a variety of ideological, social, and personal reasons. The ways that Tibetans responded to revolutionary activists’ calls for political action shed light on the difficult decisions they made under particularly complex and coercive conditions. Political calculations, revolutionary ideology, youthful enthusiasm, fear, and mob mentality all played roles in motivating Tibetan participants in Mao-era campaigns. The diversity of these Tibetan experiences and the extent of local involvement in state-sponsored attacks on religious leaders and institutions in Gyalthang during the Cultural Revolution have been largely left out of the historiographical record. -

Nameless Art in the Mao Era

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2017 Nameless Art in the Mao Era Tianchu Gao College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, and the Modern Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Gao, Tianchu, "Nameless Art in the Mao Era" (2017). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1091. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1091 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Nameless Art in the Mao Era A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in Department of Art and Art History from The College of William and Mary by Tianchu (Jane) Gao 高天楚 Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, Non-Honors) ________________________________________ Xin Wu, Director ________________________________________ Sibel Zandi-Sayek ________________________________________ Charles Palermo ________________________________________ Michael Gibbs Hill Williamsburg, VA May 2, 2017 ABSTRACT This research project focuses on the first generation of No Name (wuming 無名), an underground art group in the Cultural Revolution which secretly practiced art countering the official Socialist Realism because of its non-realist visual language and art-for-art’s-sake philosophy. These artists took advantage of their worker status to learn and practice art legitimately in the Mass Art System of the time. They developed their particular style and vision of art from their amateur art training, forbidden visual and textual sources in the underground cultural sphere, and official theoretical debates on art. -

Master for Quark6

Special feature s e Finding a Place for v i a t c n i the Victims e h p s c The Problem in Writing the History of the Cultural Revolution r e p YOUQIN WANG This paper argues that acknowledging individual victims had been a crucial problem in writing the history of the Cultural Revolution and represents the major division between the official history and the parallel history. The author discusses the victims in the history of the Cultural Revolution from factual, interpretational and methodological aspects. Prologue: A Blocked Web topic “official history and parallel history” of the Cultural Memorial Revolution. In this paper I will argue that acknowledging individual vic - n October of 2000, I launched a website, www.chinese- tims has been a crucial problem in writing the history of the memorial.org , to record the names of the people who Cultural Revolution and represents the major division be - Idied from persecution during the Cultural Revolution. tween the official history that the Chinese government has Through years of research, involving over a thousand inter - allowed to be published and the parallel history that cannot views, I had compiled the stories of hundreds of victims, and pass the censorship on publications in China. As of today, placed them on the website. By clicking on the alphabeti - no published scholarly papers have analyzed the difference cally-listed names, a user could access a victim’s personal in - between the two resulting branches in historical writings on formation, such as age, job, date and location of death, and the Cultural Revolution. -

© 2020 Thomson Reuters. No Claim to Original U.S. Government Works. 1 AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, V...., Not Reported in Atl

AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/Counterclaim-Defendant, v...., Not Reported in Atl.... 2020 WL 7024929 Only the Westlaw citation is currently available. MEMORANDUM OPINION UNPUBLISHED OPINION. CHECK *1 AB Stable VIII LLC (“Seller”) is an indirect subsidiary COURT RULES BEFORE CITING. of Dajia Insurance Group, Ltd. (“Dajia”), a corporation organized under the law of the People's Republic of China. Court of Chancery of Delaware. Dajia is the successor to Anbang Insurance Group., Ltd. (“Anbang”), which was also a corporation organized under AB STABLE VIII LLC, Plaintiff/ the law of the People's Republic of China. For simplicity, Counterclaim-Defendant, and because Anbang was the pertinent entity for much of v. the relevant period, this decision refers to both companies as MAPS HOTELS AND RESORTS ONE LLC, “Anbang.” MIRAE ASSET CAPITAL CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET DAEWOO CO., LTD., MIRAE ASSET Through Seller, Anbang owns all of the member interests in GLOBAL INVESTMENTS, CO., LTD., and Strategic Hotels & Resorts LLC (“Strategic,” “SHR,” or the MIRAE ASSET LIFE INSURANCE CO., “Company”), a Delaware limited liability company. Strategic in turn owns all of the member interests in fifteen limited LTD., Defendants/Counterclaim-Plaintiffs. liability companies, each of which owns a luxury hotel. C.A. No. 2020-0310-JTL | Under a Sale and Purchase Agreement dated September 10, Date Submitted: October 28, 2020 2019 (the “Sale Agreement” or “SA”), Seller agreed to sell | all of the member interests in Strategic to MAPS Hotel and Date Decided: November 30, 2020 Resorts One LLC (“Buyer”) for a total purchase price of $5.8 billion (the “Transaction”). -

The Beijing University Student Movement in the Hundred Flowers

The Beijing University Student Movement in the Hundred Flowers Campaign in 1957 Yidi Wu Senior Honors, History Department, Oberlin College April 29, 2011 Advisor: David E. Kelley Wu‐Beijing University Student Movement in 1957 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................. 4 Chapter 1: The Hundred Flowers Movement in Historical Perspective..................... 6 Domestic Background.......................................................................................... 6 International Crises and Mao’s Response............................................................ 9 Fragrant Flowers or Poisonous Weeds ............................................................... 13 Chapter 2: May 19th Student Movement at Beijing University ............................... 20 Beijing University before the Movement .......................................................... 20 Repertoires of the Movement.............................................................................. 23 Student Organizations......................................................................................... 36 Different Framings.............................................................................................. 38 Political Opportunities and Constraints ............................................................. 42 A Tragic Ending ................................................................................................. 46 Chapter 3: Reflections on