A Textual Analysis and Comparison of the Taketori Monogatari and Cupid

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

Jomon: 11Th to 3Rd Century BCE Yayoi

Outline Lecture Sixteen—Early Japanese Mythology and Shinto Ethics General Chronology: Jomon: 11th to 3rd century B.C.E. Yayoi: 3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E. Tomb: 3rd to 6th C.E. Yamato: 6th to 7th C.E. I) Prehistoric Origins a) Early Japanese history shrouded in obscurity i) Writing did not develop in Japan until 6th century C.E. ii) No remains of cities or other large scale settlements iii) Theories of origins of earliest settlers b) Jomon (Roughly 11th to 3rd century B.C.E.) i) “Rope-pattern” pottery ii) Hunter-gathering settlements iii) Lack of social stratification? c) Yayoi (3rd B.C.E. to 3rd C.E.) i) Simultaneous introduction of irrigation, bronze, and iron contributing to revolutionary changes (1) Impact of change in continental civilizations tend to be more gradual (2) In Japan, effect of changes are more dramatic due to its isolation (a) Foreign elements trickle in, then blend with indigenous elements (b) Creating a distinctive synthesis in “petri-dish” (pea-tree) environment ii) Increasing signs of specialization and social stratification (1) Objects of art—less primitive, more self-conscious (2) Late Yayoi burial practices d) Tomb or Kofun Period (3rd to 7th) i) Large and extravagant tombs in modern day Osaka ii) What beliefs about the afterlife do they reflect? (1) Two strains in Japanese religious cosmology iii) Emergence of a powerful mounted warrior class iv) Regional aristocracies each with its clan name (1) Uji vs. Be (2) Dramatic increase in social stratification e) Yamato State (6th to 8th C.E.) II) Yamato’s Constructions -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

Artful Adventures JAPAN an Interactive Guide for Families 56

Artful Adventures JAPAN An interactive guide for families 56 Your Japanese Adventure Awaits You! f See inside for details JAPAN Japan is a country located on the other side of the world from the United States. It is a group of islands, called an archipelago. Japan is a very old country and the Japanese people have been making beautiful artwork for thousands of years. Today we are going to look at ancient objects from Japan as well as more recent works of Japanese art. Go down the stairs to the lower level of the Museum. At the bottom of the steps, turn left and walk through the Chinese gallery to the Japanese gallery. Find a clay pot with swirling patterns on it (see picture to the left). This pot was made between 2,500 and 1,000 b.c., during the Late Jōmon period—it is between 3,000 and 4,500 years old! The people who lived in Japan at this time were hunter-gatherers, which means that they hunted wild animals and gathered roots and plants for food. The Jomon people started forming small communities, and began to make objects that were both beautiful and useful— like this pot which is decorated with an interesting pattern and was used for storage. Take a close look at the designs on this pot. Can you think of some words to describe these designs? Japanese, Middle to Late Jōmon period, ca. 3500–ca. 1000 B.C.: jar. Earthenware, h. 26.0 cm. 1. ............................................................................................................. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund (2002-297). -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

Matrix: a Journal for Matricultural Studies “In the Beginning, Woman

Volume 02, Issue 1 March 2021 Pg. 13-33 Matrix: A Journal for Matricultural Studies M https://www.networkonculture.ca/activities/matrix “In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun”: Takamure Itsue’s Historical Reconstructions as Matricultural Explorations YASUKO SATO, PhD Abstract Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), the most distinguished pioneer of feminist historiography in Japan, identified Japan’s antiquity as a matricultural society with the use of the phrase ‘women-centered culture’ (josei chūshin no bunka). The ancient classics of Japan informed her about the maternalistic values embodied in matrilocal residence patterns, and in women’s beauty, intelligence, and radiance. Her scholarship provided the first strictly empirical verification of the famous line from Hiratsuka Raichō (1886-1971), “In the beginning, woman was the sun.” Takamure recognized matricentric structures as the socioeconomic conditions necessary for women to express their inner genius, participate fully in public life, and live like goddesses. This paper explores Takamure’s reconstruction of the marriage rules of ancient Japanese society and her pursuit of the underlying principles of matriculture. Like Hiratsuka, Takamure was a maternalist feminist who advocated the centrality of women’s identity as mothers in feminist struggles and upheld maternal empowerment as the ultimate basis of women’s empowerment. This epochal insight into the ‘woman question’ merits serious analytic attention because the principle of formal equality still visibly disadvantages women with children. Keywords Japanese women, Ancient Japan, matriculture, Takamure Itsue, Hiratsuka Raicho ***** Takamure Itsue (1894-1964), pionière éminente de l'historiographie feministe au Japon, a découvert dans l'antiquité japonaise une société matricuturelle qu'elle a identifiée comme: une 'société centrée sur les femmes' (josei chūshin no bunka) ou société gynocentrique. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

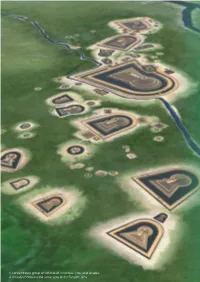

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262 -

Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1992 19/2-3 Rites and Rituals of the Kofun Period I s h in o H ironobu 石野博信 The rituals of the Kofun period were closely connected with both daily life and political affairs. The chieftain presided over the principal rites, whether in the mountains, on the rivers, or along the roadsides. The chieftain’s funeral was the preeminent rite, with a tomb mound, or kofun, constructed as its finale. The many and varied kofun rituals have been discussed elsewhere;1 here I shall concentrate on other kami rites and their departure from Yayoi practices. A Ritual Revolution Around AD 190, following a period of warfare called the “Wa Unrest,” the overall leadership of Wa was assumed by Himiko [Pimiko], female ruler of the petty kingdom of Yamatai. Beginning in 239 she opened diplomatic relations with the Wei court in China as the monarch of Wa, and she died around 248. Makimuku 1 type pottery appeared around 190; in 220 or so it was followed by Makimuku 2,and then by Makimuku 3, in about 250. The 92-meter-long keyhole-shaped Makimuku Ishizuka tomb in Sakurai City, Nara, was constructed in the first half of the third century; in the latter half of the same century the Hashihaka tomb was built. Hence the reign of Himiko, circa 190 to 248,corresponds to the appearance of key hole-shaped tombs. It was the dawn of the Kofun period and a formative time in Kofun-period ritual. In the Initial Kofun, by which I mean the period traditionally assigned to the very end of the Yayoi, bronze ritual objects were smashed, dis * This article is a partial translation of the introductory essay to volume 3 of Ish in o et al. -

Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals

Kokugakuin Univercity Museum Origin of Shinto : Ancient Japanese Rituals 14 September (Sat.) - 10 December (Sun.) , 2017 № Title Provenance Date Collection ■ Introduction 1 Mirror with Design of Seven arcs Okinoshima site, Munakata city, Fukuoka pref. Kofun period, 4th century Owned by Kokugakuin University Museum ■ ChapterⅠ: What is "Sinto " ? 1:Views of "Shinto " in the "Nihon Shyoki " : "Shinto " as the state religion Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.21 Edited in 720, Nara period 2 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Yomei " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 3 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Kotoku " Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.20 Edited in 720, Nara period 4 Edited by Prince Toneri and others Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "The record before the enthronement of Emperor Bidatsu" Published in Edo period Edited in 779, Nara period 5 To Daiwajo Toseiden (Eastern Expedition of the Great Tang Monk) Edited by Omi Mifune Owned by Kokugakuin University Library Published in Edo period Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan), vol.25 Edited in 720, Nara period 6 Edited by Prince Toneri Owned by Kokugakuin University Library "October, the 3rd year of Taika (647)" Published in Edo period 2:The word of "Shinto " : The Shinto view of the spirit Nihon shoki (Chronicles of Japan) vol.19 -

Japanese Demon Lore Noriko T

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 1-1-2010 Japanese Demon Lore Noriko T. Reider [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Reider, N. T. (2010). Japanese demon lore: Oni, from ancient times to the present. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Japanese Demon Lore Oni from Ancient Times to the Present Japanese Demon Lore Oni from Ancient Times to the Present Noriko T. Reider U S U P L, U Copyright © 2010 Utah State University Press All rights reserved Utah State University Press Logan, Utah 84322 Cover: Artist Unknown, Japanese; Minister Kibi’s Adventures in China, Scroll 2 (detail); Japanese, Heian period, 12th century; Handscroll; ink, color, and gold on paper; 32.04 x 458.7 cm (12 5/8 x 180 9/16 in.); Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; William Sturgis Bigelow Collection, by exchange, 32.131.2. ISBN: 978-0-87421-793-3 (cloth) IISBN: 978-0-87421-794-0 (e-book) Manufactured in the United States of America Printed on acid-free, recycled paper Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Reider, Noriko T. Japanese demon lore : oni from ancient times to the present / Noriko T. Reider.