The Tale of Genji” and Its Selected Adaptations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Aesthetics and the Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] T

Japanese Aesthetics and The Tale of Genji Liya Li Department of English SUNY/Rockland Community College [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Themes and Uses 2. Instructor’s Introduction 3. Student Readings 4. Discussion Questions 5. Sample Writing Assignments 6. Further Reading and Resources 1. Themes and Uses Using an excerpt from the chapter “The Sacred Tree,” this unit offers a guide to a close examination of Japanese aesthetics in The Tale of Genji (ca.1010). This two-session lesson plan can be used in World Literature courses or any course that teaches components of Zen Buddhism or Japanese aesthetics (e.g. Introduction to Buddhism, the History of Buddhism, Philosophy, Japanese History, Asian Literature, or World Religion). Specifically, the lesson plan aims at helping students develop a deeper appreciation for both the novel and important concepts of Japanese aesthetics. Over the centuries since its composition, Genji has been read through the lenses of some of the following terms, which are explored in this unit: • miyabi (“courtly elegance”; refers to the aristocracy’s privileging of a refined aesthetic sensibility and an indirectness of expression) • mono no aware (the “poignant beauty of things;” describes a cultivated sensitivity to the ineluctable transience of the world) • wabi-sabi (wabi can be translated as “rustic beauty” and sabi as “desolate beauty;” the qualities usually associated with wabi and sabi are austerity, imperfection, and a palpable sense of the passage of time. • yûgen (an emotion, a sentiment, or a mood so subtle and profoundly elegant that it is beyond what words can describe) For further explanation of these concepts, see the unit “Buddhism and Japanese Aesthetics” (forthcoming on the ExEAS website.) 2. -

Noh and Kyogen

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ NOH AND KYOGEN The world’s oldest living theater Noh performance Scene of Hirota Yukitoshi in the noh drama Kagetsu (Flowers and Moon) performed at the 49th Commemorative Noh event. (Photo courtesy of The Nohgaku Performers’ Association) Noh and kyogen are two of Japan’s four variety of centuries-old theatrical traditions forms of classical theater, the other two being were touring and performing at temples, kabuki and bunraku. Noh, which in its shrines, and festivals, often with the broadest sense includes the comic theater patronage of the nobility. The performing kyogen, developed as a distinctive theatrical genre called sarugaku was one of these form in the 14th century, making it the oldest traditions. The brilliant playwrights and actors extant professional theater in the world. Kan’ami (1333–1384) and his son Zeami Although noh and kyogen developed together (1363–1443) transformed sarugaku into noh and are inseparable, they are in many ways in basically the same form as it is still exact opposites. Noh is fundamentally a performed today. Kan’ami introduced the symbolic theater with primary importance music and dance elements of the popular attached to ritual and suggestion in a rarefied entertainment kuse-mai into sarugaku, and he aesthetic atmosphere. In kyogen, on the other attracted the attention and patronage of hand, primary importance is attached to Muromachi shogun Ashikaga Yoshimitsu making people laugh. (1358–1408). After Kan’ami’s death, Zeami became head of the Kanze troupe. The continued patronage of Yoshimitsu gave him the chance History of the Noh to further refine the noh aesthetic principles of Theater monomane (the imitation of things) and yugen, a Zen-influenced aesthetic ideal emphasizing In the early 14th century, acting troupes in a the suggestion of mystery and depth. -

Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/2: 269–296 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture R. Keller Kimbrough Tourists in Paradise Writing the Pure Land in Medieval Japanese Fiction Late-medieval Japanese fiction contains numerous accounts of lay and monastic travelers to the Pure Land and other extra-human realms. In many cases, the “tourists” are granted guided tours, after which they are returned to the mun- dane world in order to tell of their unusual experiences. This article explores several of these stories from around the sixteenth century, including, most prominently, Fuji no hitoana sōshi, Tengu no dairi, and a section of Seiganji engi. I discuss the plots and conventions of these and other narratives, most of which appear to be based upon earlier oral tales employed in preaching and fund-raising, in order to illuminate their implications for our understanding of Pure Land-oriented Buddhism in late-medieval Japan. I also seek to demon- strate the diversity and subjectivity of Pure Land religious experience, and the sometimes startling gap between orthodox doctrinal and popular vernacular representations of Pure Land practices and beliefs. keywords: otogizōshi – jisha engi – shaji engi – Fuji no hitoana sōshi – Bishamon no honji – Tengu no dairi – Seiganji engi – hell – travel R. Keller Kimbrough is an assistant professor of Japanese Literature at the University of Colorado at Boulder. 269 ccording to an anonymous work of fifteenth- or early sixteenth- century Japanese fiction by the name of Chōhōji yomigaeri no sōshi 長宝 寺よみがへりの草紙 [Back from the dead at Chōhōji Temple], the Japa- Anese Buddhist nun Keishin dropped dead on the sixth day of the sixth month of Eikyō 11 (1439), made her way to the court of King Enma, ruler of the under- world, and there received the King’s personal religious instruction and a trau- matic tour of hell. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bk827db Author Chudnow, Matthew Thomas Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. -

Shaping Darkness in Hyakki Yagyō Emaki

Asian Studies III (XIX), 1 (2015), pp.9–27 Shaping Darkness in hyakki yagyō emaki Raluca NICOLAE* Abstract In Japanese culture, the yōkai, the numinous creatures inhabiting the other world and, sometimes, the boundary between our world and the other, are obvious manifestations of the feeling of fear, “translated” into text and image. Among the numerous emaki in which the yōkai appear, there is a specific type, called hyakki yagyō (the night parade of one hundred demons), where all sorts and sizes of monsters flock together to enjoy themselves at night, but, in the end, are scattered away by the first beams of light or by the mysterious darani no hi, the fire produced by a powerful magical invocation, used in the Buddhist sect Shingon. The nexus of this emakimono is their great number, hyakki, (one hundred demons being a generic term which encompasses a large variety of yōkai and oni) as well as the night––the very time when darkness becomes flesh and blood and starts marching on the streets. Keywords: yōkai, night, parade, painted scrolls, fear Izvleček Yōkai (prikazni, demoni) so v japonski kulturi nadnaravna bitja, ki naseljuje drug svet in včasih tudi mejo med našim in drugim svetom ter so očitno manifestacija občutka strahu “prevedena” v besedila in podobe. Med številnimi slikami na zvitkih (emaki), kjer se prikazni pojavljajo, obstaja poseben tip, ki se imenuje hyakki yagyō (nočna parade stotih demonov), kjer se zberejo pošasti različne vrste in velikosti, da bi uživali v noči, vendar jih na koncu preženejo prvi žarki svetlobe ali skrivnosten darani no hi, ogenj, ki se pojavi z močnim magičnim zaklinjanje in se uporablja pri budistični sekti Shingon. -

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Reading and Re-Envisioning the Tale of Genji Through the Ages

Symbols of each chapters of The Tale of Genji Thematic Exhibition Ⅳ Dissemination of the Genji Tale from the Genji-kō Incense Game Reading and Re-envisioning The Tale of Genji attracted many readers, irrespective of gender, through "Genji-kō" is a name of the kumikō incense game which is tasting different the beauty of the text and its thorough depictions fragrances and guessing the name, developed in Edo period. Participants The Tale of Genji of every aspect of classical court culture, its skillful would taste 5 different fragrances and draw a horizontal line to connect the psychological portrayals of the characters, and same fragrance. Thus drawn, figures appear in 52 different shapes, matching through the Ages its diverse world view based on Japanese the number of chapters of The Tale of Genji except the first and the last ones, and Chinese literature, various arts, and and they are called "Genji-kō" design. The "Genji-kō" design often appears in Buddhism. Not only did it have a significant impact on various traditional craft works as well as design of Japanese confectionery later literary works, but its influence can also be seen in associated with the story of The Tale of Genji. Japanese performing arts, such as Noh theater, and cultural arts, such as incense ceremony (kōdō), and tea ceremony (sadō), as well as the arts and crafts that accompany them. 46 37 28 1 9 1 0 1 “The Tale of Genji,” written Shiigamoto Yokobue Nowaki Usugumo Sakaki Kiritsubo At the same time, as a narrative that features Art Museum & The Tokugawa 2020 / By Hōsa Library, City of Nagoya Nov. -

The Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2013 Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation Allan Persinger University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Persinger, Allan, "Foxfire: the Selected Poems of Yosa Buson, a Translation" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 748. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/748 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee May 2013 ABSTRACT FOXFIRE: THE SELECTED POEMS OF YOSA BUSON A TRANSLATION By Allan Persinger The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, 2013 Under the Supervision of Professor Kimberly M. Blaeser My dissertation is a creative translation from Japanese into English of the poetry of Yosa Buson, an 18th century (1716 – 1783) poet. Buson is considered to be one of the most important of the Edo Era poets and is still influential in modern Japanese literature. By taking account of Japanese culture, identity and aesthetics the dissertation project bridges the gap between American and Japanese poetics, while at the same time revealing the complexity of thought in Buson's poetry and bringing the target audience closer to the text of a powerful and mov- ing writer. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Soteriology in the Female-Spirit Noh Plays of Konparu Zenchiku DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in East Asian Languages and Literatures by Matthew Chudnow Dissertation Committee: Associate Professor Susan Blakeley Klein, Chair Professor Emerita Anne Walthall Professor Michael Fuller 2017 © 2017 Matthew Chudnow DEDICATION To my Grandmother and my friend Kristen オンバサラダルマキリソワカ Windows rattle with contempt, Peeling back a ring of dead roses. Soon it will rain blue landscapes, Leading us to suffocation. The walls structured high in a circle of oiled brick And legs of tin- Stonehenge tumbles. Rozz Williams Electra Descending ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iv CURRICULUM VITAE v ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION vi INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: Soteriological Conflict and 14 Defining Female-Spirit Noh Plays CHAPTER 2: Combinatory Religious Systems and 32 Their Influence on Female-Spirit Noh CHAPTER 3: The Kōfukuji-Kasuga Complex- Institutional 61 History, the Daijōin Political Dispute and Its Impact on Zenchiku’s Patronage and Worldview CHAPTER 4: Stasis, Realization, and Ambiguity: The Dynamics 95 of Nyonin Jōbutsu in Yōkihi, Tamakazura, and Nonomiya CONCLUSION 155 BIBLIOGRAPHY 163 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is the culmination of years of research supported by the department of East Asian Languages & Literatures at the University of California, Irvine. It would not have been possible without the support and dedication of a group of tireless individuals. I would like to acknowledge the University of California, Irvine’s School of Humanities support for my research through a Summer Dissertation Fellowship. I would also like to extend a special thanks to Professor Joan Piggot of the University of Southern California for facilitating my enrollment in sessions of her Summer Kanbun Workshop, which provided me with linguistic and research skills towards the completion of my dissertation. -

Introduction This Exhibition Celebrates the Spectacular Artistic Tradition

Introduction This exhibition celebrates the spectacular artistic tradition inspired by The Tale of Genji, a monument of world literature created in the early eleventh century, and traces the evolution and reception of its imagery through the following ten centuries. The author, the noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu, centered her narrative on the “radiant Genji” (hikaru Genji), the son of an emperor who is demoted to commoner status and is therefore disqualified from ever ascending the throne. With an insatiable desire to recover his lost standing, Genji seeks out countless amorous encounters with women who might help him revive his imperial lineage. Readers have long reveled in the amusing accounts of Genji’s romantic liaisons and in the dazzling descriptions of the courtly splendor of the Heian period (794–1185). The tale has been equally appreciated, however, as social and political commentary, aesthetic theory, Buddhist philosophy, a behavioral guide, and a source of insight into human nature. Offering much more than romance, The Tale of Genji proved meaningful not only for men and women of the aristocracy but also for Buddhist adherents and institutions, military leaders and their families, and merchants and townspeople. The galleries that follow present the full spectrum of Genji-related works of art created for diverse patrons by the most accomplished Japanese artists of the past millennium. The exhibition also sheds new light on the tale’s author and her female characters, and on the women readers, artists, calligraphers, and commentators who played a crucial role in ensuring the continued relevance of this classic text. The manuscripts, paintings, calligraphy, and decorative arts on display demonstrate sophisticated and surprising interpretations of the story that promise to enrich our understanding of Murasaki’s tale today. -

Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Laura Nuffer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Studies Commons, and the Medieval Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nuffer, Laura, "Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1389. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1389 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Of Mice and Maidens: Ideologies of Interspecies Romance in Late Medieval and Early Modern Japan Abstract Interspecies marriage (irui kon'in) has long been a central theme in Japanese literature and folklore. Frequently dismissed as fairytales, stories of interspecies marriage illuminate contemporaneous conceptions of the animal-human boundary and the anxieties surrounding it. This dissertation contributes to the emerging field of animal studies yb examining otogizoshi (Muromachi/early Edo illustrated narrative fiction) concerning elationshipsr between human women and male mice. The earliest of these is Nezumi no soshi ("The Tale of the Mouse"), a fifteenth century ko-e ("small scroll") attributed to court painter Tosa Mitsunobu. Nezumi no soshi was followed roughly a century later by a group of tales collectively named after their protagonist, the mouse Gon no Kami. Unlike Nezumi no soshi, which focuses on the grief of the woman who has unwittingly married a mouse, the Gon no Kami tales contain pronounced comic elements and devote attention to the mouse-groom's perspective. -

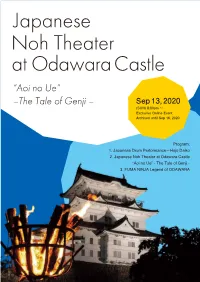

Aoi No Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00Pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived Until Sep 16, 2020

Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” –The Tale of Genji – Sep 13, 2020 (SUN) 8:00pm ~ Exclusive Online Event Archived until Sep 16, 2020 Program: 1. Japanese Drum Performance—Hojo Daiko 2. Japanese Noh Theater at Odawara Castle “Aoi no Ue” - The Tale of Genji - 3. FUMA NINJA Legend of ODAWARA The Tale of Genji is a classic work of Japanese literature dating back to the 11th century and is considered one of the first novels ever written. It was written by Murasaki Shikibu, a poet, What is Noh? novelist, and lady-in-waiting in the imperial court of Japan. During the Heian period women were discouraged from furthering their education, but Murasaki Shikibu showed great aptitude Noh is a Japanese traditional performing art born in the 14th being raised in her father’s household that had more of a progressive attitude towards the century. Since then, Noh has been performed continuously until education of women. today. It is Japan’s oldest form of theatrical performance still in existence. The word“Noh” is derived from the Japanese word The overall story of The Tale of Genji follows different storylines in the imperial Heian court. for“skill” or“talent”. The Program The themes of love, lust, friendship, loyalty, and family bonds are all examined in the novel. The The use of Noh masks convey human emotions and historical and Highlights basic story follows Genji, who is the son of the emperor and is left out of succession talks for heroes and heroines. Noh plays typically last from 2-3 hours and political reasons.