Diagnosing the Binding Constraints on Economic Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Baseline Assessment Study on Wastewater Management Belize

Caribbean Regional Fund for Wastewater Management Baseline Assessment Study on Wastewater Management Belize December 2013 Revised January 2015 Baseline Assessment Study for the GEF CReW Project: Belize December 2013 Prepared by Dr. Homero Silva Revised January 2015 CONTENTS List of Acronyms....................................................................................................................................................iii 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. The National Context ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of the Country .................................................................................................................. 4 Geographic Characteristics ................................................................................................................. 6 Economy by Sectors ............................................................................................................................ 9 The Environment .............................................................................................................................. 13 Land Use, Land Use Changes and Forestry (LULUCF) ....................................................................... 20 Disasters .......................................................................................................................................... -

Hurricanes and the Forests of Belize, Jon Friesner, 1993. Pdf 218Kb

Hurricanes and the Forests Of Belize Forest Department April 1993 Jon Friesner 1.0 Introduction Belize is situated within the hurricane belt of the tropics. It is periodically subject to hurricanes and tropical storms, particularly during the period June to July (figure 1). This report is presented in three sections. - A list of hurricanes known to have struck Belize. Several lists documenting cyclones passing across Belize have been produced. These have been supplemented where possible from archive material, concentrating on the location and degree of damage as it relates to forestry. - A map of hurricane paths across Belize. This has been produced on the GIS mapping system from data supplied by the National Climatic Data Centre, North Carolina, USA. Some additional sketch maps of hurricane paths were available from archive material. - A general discussion of matters relating to a hurricane prone forest resource. In order to most easily quote sources, and so as not to interfere with the flow of text, references are given as a number in brackets and expanded upon in the reference section. Summary of Hurricanes in Belize This report lists a total of 32 hurricanes. 1.1 On Hurricanes and Cyclones (from C.J.Neumann et al) Any closed circulation, in which the winds rotate anticlockwise in the Northern Hemisphere or clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere, is called a cyclone. Tropical cyclones refer to those circulations which develop over tropical waters, the tropical cyclone basins. The Caribbean Sea is included in the Atlantic tropical cyclone basin, one of six such basins. The others in the Northern Hemisphere are the western North Pacific (where such storms are called Typhoons), the eastern North Pacific and the northern Indian Ocean. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 256 CAYS of the BELIZE

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 256 CAYS OF THE BELIZE BARRIER REEF AND LAGOON by D . R. Stoddart, F. R. Fosberg and D. L. Spellman Issued by THE SMlTHSONlAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. April 1982 CONTENTS List of Figures List of Plates i i Abstract 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Structure and environment 5 3. Sand cays of the northern barrier reef 9 St George's East Cay Paunch Cay Sergeant' s Cay Curlew Cay Go£ f ' s Cay Seal Cay English Cay Sandbore south of English Cay Samphire Spot Rendezvous Cay Jack's Cays Skiff Sand Cay Glory Tobacco Cay South Water Cay Carrie Bow Cay Curlew Cay 5. Sand cays of the southern barrier reef 23 Silk or Queen Cays North Silk Cay Middle Silk Cay Sauth Silk Cay Samphire Cay Round Cay Pompion Cay Ranguana Cay North Spot Tom Owen's Cay Tom Owen's East Cay Tom Owen's West Cay Cays between Tom Owen's Cays and Northeast Sapodilla Cay The Sapodilla Cays Northeast Sapodilla Cay Frank 's Cays Nicolas Cay Hunting Cay Lime Cay Ragged Cay Seal Cays 5. Cays of the barrier reef lagoon A. The northern lagoon Ambergris Cay Cay Caulker Cay Chapel St George ' s Cay Cays between Cay Chapel and Belize ~ohocay Stake Bank Spanish Lookout Cay Water Cay B. The Southern Triangles Robinson Point Cay Robinson Island Spanish Cay C. Cays of the central lagoon Tobacco Range Coco Plum Cay Man-o '-War Cay Water Range Weewee Cay Cat Cay Lagoon cays between Stewart Cay and Baker's Rendezvous Jack's Cay Buttonwood Cay Trapp 's Cay Cary Cay Bugle Cay Owen Cay Scipio Cay Colson Cay Hatchet Cay Little Water Cay Laughing Bird Cay Placentia Cay Harvest Cay iii D. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

EDUCATION and MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 By

EDUCATION AND MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 by PETER RONALD HITCHEN BA (Hons) History For the award of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE April 2002 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the British neglect of education in Belize and the emergence of increased tensions between church and state, from the twin catalysts for social change of the 1931 hurricane and economic depression until independence in 1981. This conflict has revealed a contradictory web of power structures and their influence, through the medium of schools, on multi-cultural development. The fundamental argument is that despite a rhetoric- of-difference, a cohesive society was created in Belize rooted in the cultural values propagated through an often-contradictory church-state education system, and that Jesuit supremacy of Belizean education came too late to unsettle or exploit the grass-root forces of cultural synthesis. Racial conflict in Belize is more a matter of habitual rhetoric and superficial. The historiography of Belize falls broadly into two categories: Diplomatic and labour, nevertheless cultural and educational studies have developed most notably from Social Anthropology. An extensive literature review revealed that notwithstanding the emergence of a substantial historiography of education on the British Caribbean similar research has been neglected on Belize. Therefore, my own thesis fills a significant gap in the historiography of British Caribbean education. The PhD discusses the relationship between conflicting hierarchies within education and multi-cultural cohesion, not yet been fully attempted in any of the secondary literature. This is a proposition argued through substantial and original primary research, employing a mix of comparative empirical research and theoretical Sights influenced by historical sociologist Nigel Bolland to analyse the interactions of people at community level, the ubiquitous presence of the denominations, and political and hierarchical activities. -

Chapter 3 Principles, Materials and Methods Used When Reconstructing

‘Under the shade I flourish’: An environmental history of northern Belize over the last three thousand five hundred years Elizabeth Anne Cecilia Rushton BMus BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ABSTRACT Environmental histories are multi-dimensional accounts of human interaction with the environment over time. They observe how and when the environment changes (material environmental histories), and the effects of human activities upon the environment (political environmental histories). Environmental histories also consider the thoughts and feelings that humans have had towards the environment (cultural/ intellectual environmental histories). Using the methodological framework of environmental history this research, located in sub-tropical northern Belize, brings together palaeoecological records (pollen and charcoal) with archival documentary sources. This has created an interdisciplinary account which considers how the vegetation of northern Belize has changed over the last 3,500 years and, in particular, how forest resources have been used during the British Colonial period (c. AD 1800 – 1950). The palaeoecological records are derived from lake sediment cores extracted from the New River Lagoon, adjacent to the archaeological site of Lamanai. For over 3,000 years Lamanai was a Maya settlement, and then, more recently, the site of two 16th century Spanish churches and a 19th century British sugar mill. The British archival records emanate from a wide variety of sources including: 19th century import and export records, 19th century missionary letters and 19th and 20th century meteorological records and newspaper articles. The integration of these two types of record has established a temporal range of 1500 BC to the present. -

The Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1968

March 1969 225 UDC 551.515.2(261.1)"1968" THE ATLANTICHURRICANE SEASON OF 1968 ARNOLD L. SUGG and PAUL J. HEBERT' National Hurricane Center, Weather Bureau, ESSA, Miami, Fla. ABSTRACT The 1968 hurricane season in the North Atlantic area, considered in its entirety, and synoptic and statistical aspects of individual storms are discussed. 1. GENERAL SUMMARY TABLE1.-Hurricane days, 1954-1968 The two hurricanes and onetropical storm inJune Year Jan. Feb. Mar. Apr. May June July Aug. Sept. Dec. Total Nov. Oct. equaled a record established in 1886.2 While there were __-_________ two other years, 1959 and 1936, with a total of three June 1954 ___.__.__.___._..... _____ ..-.-..... 1 ..". 5 8 16 ___._1 31 tropical cyclones, each is not unique as there were two I955 ___.___...4 ..". .____ _____ ..... ._.._..". 22 28 2 .." ~ _____ 56 1956___._..__. ..-....". ___._ ..... ..". ..-.- 1 9 2 ___..3 ____ ._ 15 storms and one hurricane in those years. Two hurricanes 1957__.____.._ _._._..... ..". __.__..". 3 ..... _.___19 _._._ .._.______ 22 occurring inJune are noteworthy when one considers 1958__.___..._ _.___..... ..". _____ .".. _____ .__._14 16 5 ..____.___ 35 1959 __._....._..... __.._ .-..._.___ ..". 1 2 ..___10 11 .._______. 24 there have only been 20 since 1886. This is approximately 1960___......_ ..-.._._._ .".. .____..___4 2 ____.13 ~ ____ .____ ____. 10 one every 4 yr, rather than two for any one June. In spite 1961 ___......_..... ..-.- ..". ___.._____ .... -

Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present

DISASTER HISTORY Signi ficant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900 - Present Prepared for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Developnent Washington, D.C. 20523 Labat-Anderson Incorporated Arlington, Virginia 22201 Under Contract AID/PDC-0000-C-00-8153 INTRODUCTION The OFDA Disaster History provides information on major disasters uhich have occurred around the world since 1900. Informtion is mare complete on events since 1964 - the year the Office of Fore8jn Disaster Assistance was created - and includes details on all disasters to nhich the Office responded with assistance. No records are kept on disasters uhich occurred within the United States and its territories.* All OFDA 'declared' disasters are included - i.e., all those in uhich the Chief of the U.S. Diplmtic Mission in an affected country determined that a disaster exfsted uhich warranted U.S. govermnt response. OFDA is charged with responsibility for coordinating all USG foreign disaster relief. Significant anon-declared' disasters are also included in the History based on the following criteria: o Earthquake and volcano disasters are included if tbe mmber of people killed is at least six, or the total nmber uilled and injured is 25 or more, or at least 1,000 people art affect&, or damage is $1 million or more. o mather disasters except draught (flood, storm, cyclone, typhoon, landslide, heat wave, cold wave, etc.) are included if the drof people killed and injured totals at least 50, or 1,000 or mre are homeless or affected, or damage Is at least S1 mi 1l ion. o Drought disasters are included if the nunber affected is substantial. -

19730013840.Pdf

SATELLITE&MESOMETEOROLOQGY RESEARCH PROJECT \ \ -Department of the Geophysical Sciences 'kXXThe University of Chicago I I TORNADO OCCURRENCES RELATED TO OVERSHOOTING CLOUD-TOP HEIG-'T AS DETERMINED FROM ATS PICTURES : n M z ~~~~I~~~~~~~~~~~~- .- J It by w i ti O ·1 T. Theodore Fujita - la o ra -4 W tz z I ·,.--3 0 c :VI -.-. .. April 1972 ' o MESOLTEOtOLOGY PROJECT --- RESEARCH PAPERS 1. Report on the Chicago Tornado of March 4, 1961 - Rodger A. Brown and Tetsuya Fujita 2. ' Index to the NSSP Surface Network - Tetsuya Fujita 3.* Outline of a Technique for Precise Rectif:cation of Satellite Cloud Photographs - Tetsuya Fujita 4. Horizontal Structure of Mountain Winds - Henry A. Brown 5.* An Investigation of Developmental Processes of the Wake Depression Through Excess Pressure Analysis of Nocturnal Showers - Joseph L. Goldman 6. * Precipitation in the 1960 Flagstaff Mesometeorological Network - Kenneth A. Styber 7. ** On a Method of Single- and Dual-Image Photogrammetry of Panoramic Aerial Photographs - Tetsuya Fujita 8. A Review of Researches on Analytical Mesometeorology - Tetsuya Fujita 9. * Meteorological Interpretations of Convective Nephsystems Appearing in TIROS Cloud Photographs - Tetsuya Fujita, Toshimitsu Ushijima, William A. Hass, and George T. Dellert, Jr. 10. Study of the Development of Prefrontal Squall-Systems Using NSSP Network Data - Joseph L. Goldman 11. Analysis of Selected Aircraft Data from NSSP Operation, 1962 - Tetsuya Fujita 12. Study of a Long Condensation Trail Photographed by TIROS I - Toshimitsu Ushijima 13. A Technique for Precise Analysis of Satellite Data; Volume I - Photogrammetry (Published as MSL Report No. 14) - Tetsuya Fujita 14. Investigation of a Summer Jet Stream Using TIROS and Aerological Data - Kozo Ninomiya 15. -

Saint Lucia: a Case Study

Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Transport Infrastructure in the Caribbean: Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) Saint Lucia: A case study Climate Change Impacts on Coastal Transportation Infrastructure in the Caribbean: Enhancing the Adaptive Capacity of Small Island Developing States (SIDS) SAINT LUCIA: A case study © 2018, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations or its officials or Member States. The designation employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Photocopies and reproductions of excerpts are allowed with proper credits. This publication has not been formally edited. UNCTAD/DTL/TLB/2018/3 ii NOTE Please cite as UNCTAD (2017) Climate change impacts on coastal transport infrastructure in the Caribbean: enhancing the adaptive capacity of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), SAINT LUCIA: A case study. UNDA project 1415O. For further information about the project and relevant documentation, see SIDSport-ClimateAdapt.unctad.org. For further information about UNCTAD's related work, please contact the UNCTAD secretariat's Policy and Legislation Section at [email protected] or consult the website at unctad.org/ttl/legal. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by Isavela Monioudi (University of the Aegean) for UNCTAD, with contribution from Vasantha Chase, in support of UNCTAD’s technical assistance project "Climate change impacts on coastal transport infrastructure in the Caribbean: enhancing the adaptive capacity of Small Island Developing States (SIDS)", funded under the UN Development Account (UNDA project 1415O). -

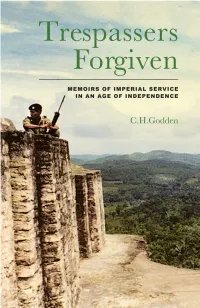

C-H-Godden-Trespassers-Forgiven

TRESPASSERS FORGIVEN Charles H. Godden led a long and interesting career in the Colonial Office and HM Diplomatic Service, beginning in 1950 following his military service in the Second World War. During that time he served abroad in Belize (formerly British Honduras) twice. He was also Secretary to a United Nations Mission to the High Commission Territories of Southern Africa, Private Secretary to FCO Ministers of State and held positions in Finland, Jamaica, Haiti and Anguilla, from which territory he retired as Governor in 1984. He was made CBE in 1981. TRESPASSERS FORGIVEN Memoirs of Imperial Service in an Age of Independence C. H. GODDEN The Radcliffe Press LONDON ⋅ NEW YORK Published in 2009 by The Radcliffe Press 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU Distributed in the United States and Canada Exclusively by Palgrave Macmillan 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © 2009 Charles H. Godden The right of Charles H. Godden to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN 978 1 84511 780 1 A full CIP record is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress Catalog card: available Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham Copy-edited and typeset by Oxford Publishing Services, Oxford DEDICATED, WITH LOVE, TO THE MEMORY OF FLORENCE WHO ALSO SERVED; FOR JAN AND SUE, WHO SHARED THE EXPERIENCE, AND LAURA AND JAMES – SUCCESSORS Contents Illustrations ix Acronyms and Abbreviations xi Acknowledgements xiii Extract from Aldous Huxley’s Beyond the Mexique Bay (1934) xv Map of British Settlements in the Eighteenth Century xvi Map of Belize (formerly British Honduras) xvii Prologue 1 1. -

1973 Variations of Hurricane Heat Potential in the Philippine Sea and the Gulf of Mexico

1973 VARIATIONS OF HURRICANE HEAT POTENTIAL IN THE PHILIPPINE SEA AND THE GULF OF MEXICO Paul Dennis Shuman NPS-58LR74031 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS 1973 VARIATIONS OF HURRICANE HEAT POTENTIAL IN THE PHILIPPINE SEA AND THE GULP 1 OF MEXICO by Paul Dennis Shuman March 1974 Thesis Advisor: D. F. LeiDDer Prepared for: Office of Naval Research NASA-Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Code 400P and Code 481 Zack H. Byrns, Code TF6 Arlington, VA 22217 Houston, TX 77058 AppAovzd fan. public neJLiLCUbz.; dUtAAJbution wnLbnittd. T160853 DUDLEY KiMUX LIBRARY NAVAL l-OSTGRADUATE SCHOOL iviONTEREY. CALIFORNIA 93940 1973 Variations of Hurricane Heat Potential in the Philippine Sea and the Gulf of Mexico by Paul Dennis Shuman Lieutenant Commander, United States Navy B.S., United States Naval Academy, 1965 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN OCEANOGRAPHY from the NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL March 197^ 7%esis a. i DUDLEY KNOX LIBRARY NAVAL POSTGRADUATE Si MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California Rear Admiral Mason Freeman Jack R. Borsting Superintendent Provost This thesis is prepared in conjunction with research supported in part by Office of Naval Research under Project Order No. PO-0121 and NASA-Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center under Project Order No. T-4650B. Reproduction of all or part of this report is authorized. Released as a Technical Report by: ABSTRACT The 1973 summer growth of hurricane heat potential (HHP) and its relation to tropical cyclones was studied in the Philippine Sea and the Gulf of Mexico on a monthly basis.