EDUCATION and MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

A Time Bomb Lies Buried: Fiji's Road to Independence

1. Introduction In his Christmas message to the people of Fiji, Governor Sir Kenneth Maddocks described 1961 as a year of `peaceful progress'.1 The memory of industrial disturbance and a brief period of rioting and looting in Suva in 1959 was fading rapidly.2 The nascent trade union movement, multi-ethnic in character, which had precipitated the strike, was beginning to fracture along racial lines. The leading Fijian chiefs, stunned by the unexpectedly unruly behaviour of their people, warned them against associating with people of other races, emphasising the importance of loyalty to the Crown and respect for law and order.3 The strike in the sugar industry, too, was over. Though not violent in character, the strike had caused much damage to an economy dependent on sugar, it bitterly split the Indo-Fijian community and polarised the political atmosphere.4 A commission of inquiry headed by Sir Malcolm Trustram Eve (later Lord Silsoe) was appointed to investigate the causes of the dispute and to recommend a new contract between the growers, predominantly Indo-Fijians, and the monopoly miller, the Australian Colonial Sugar Refining Company (CSR). The recommendations of the Burns Commission Ð as it came to be known, after its chairman, the former governor of the Gold Coast (Ghana), Sir Alan Burns Ð into the natural resources and population of Fiji were being scrutinised by the government.5 The construction of roads, bridges, wharves, schools, hospital buildings and water supply schemes was moving apace. The governor had good reason to hope for `peaceful progress'. Rather more difficult was the issue of political reform, but the governor's message announced that constitutional changes would be introduced. -

Sir Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture.Pub

The Sir Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture Third Annual Aviation Industry Conference Week July 2010 W R Tannock BSc (Hons), CEng, FRAeS To be offered the opportunity to deliver the first Sir ber of the New Zealand Territorial Force, left these Geoffrey Roberts Memorial Lecture is indeed an shores for UK, at his own expense, to join the Royal honour and I thank The Guild of Air Pilots and Air Air Force. Although he failed his first medical ex- Navigators, The Royal New Zealand Air Force, The amination - his health was "rundown" after seven Royal Aeronautical Society and The Aviation Indus- weeks at sea - he was soon accepted into the RAF on try Association for inviting me to do so. a short service commission with the rank of Acting Pilot Officer – just as well since he had less than 10 The founding organisations determined that the shillings in its pocket. After the mandatory period of subject of the lecture would be “on any significant " square bashing" and a short period of, as Des Lyn- civilian or military aviation topic, this can include skey used to call it, " knife and fork school", he was design, testing of significant aircraft, significant off to flying training, passing successfully as an technical or safety initiatives or the contributions of "above-average" student graduating with a major civilian or military aviation personnel”. I feel "distinguished pass". it is entirely appropriate that this inaugural lecture should commemorate the life and times of Sir Geof- Geoffrey Roberts was posted to India to fly light- frey himself considering the significant contribution day bombers on the Northwest frontier where he was he made to both military and civil aviation. -

The Effects of Teacher Certification and Experience on Student

THE EFFECTS OF TEACHER CERTIFICATION AND EXPERIENCE ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT ON PRIMARY SCHOOL EXAMINATION IN BELIZEAN PRIMARY SCHOOLS By CARMEN JANE LOPEZ Bachelor of Science in Biology Education University College of Belize Belize City, Belize 1997 Master of Arts in Educational Leadership University of North Florida Jacksonville, Florida 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION July, 2012 THE EFFECTS OF TEACHER CERTIFICATION AND EXPERIENCE ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT ON PRIMARY SCHOOL EXAMINATION IN BELIZEAN PRIMARY SCHOOLS Dissertation Approved: Dissertation Adviser’s Dr. Ed Harris Dissertation Adviser Committee Member Dr. Mwarumba Mwavita Committee Member Dr. Stephen Wanger Committee Member Dr. Jesse Mendez Committee Member Dr. Pasha Antonenko Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 History of Teacher Education in Belize ...................................................................3 Problem Statement ...................................................................................................4 Purpose of Study ......................................................................................................5 Research Questions and Hypotheses………………………………………………5 Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................7 -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 18 February 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Fifth session Geneva, 4-15 May 2009 NATIONAL REPORT SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH PARAGRAPH 15 (A) OF THE ANNEX TO HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL RESOLUTION 5/1 * Belize _________________________ * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.09- A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1. Belize is firmly committed to the protection and promotion of human rights as evidenced by its Constitution, domestic legislation, adherence to international treaties and existing national agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). 2. Belizean culture, democratic history and legal tradition has infused in Belizean society and government a deep respect for those fundamental human rights articulated in Part II of the Belize Constitution. Such fundamental freedoms as the right to assembly, the right to free speech and the right to due process are vigilantly guarded by Belizeans themselves. 3. As a developing country Belize views development as inextricably bound to the fulfilment of human rights making the right to development a fundamental right itself as asserted by the Declaration on the Right to Development. Thus, the Government of Belize has consistently adopted a human rights based approach in development planning, social services and general policy formulation and execution. 4. Belize’s national report for the Universal Periodic Review has been prepared in accordance with the General Guidelines for the Preparation of Information under the Universal Periodic Review, decision 6/102, as circulated adopted by the Human Rights Council on 27 September 2007. -

Pacific Entomologist 1925-1966

RECOLLEcnONS OF A Pacific Entomologist 1925-1966 WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY THE AUTHOR R.W. Paine Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research Canberra 1994 The Australian Centre for Intemational Agricultural Research (ACIAR) was established in June 1982 by an Act of Ihe Australian Parliament. lis primary mandate is 10 help identify agricultural problems in developing countries and to commission collaborative research between Australian and developing country researchers in fields where Australia has special competence. Where trade names ore used this does not constitute endorsement of nar discrimination against any product by the Centre. This peer-reviewed series contains the results of original research supported by ACIAR, or malerial deemed relevant 10 ACIAR's research and development objectives. The series is distributed intemationally, with an emphasis on developing countries. © Australian Centre for Intemational Agricultural Research GPO Box 157 t Conberra, Australia 2601 . Paine, R.w. 1994. Recollections of a Pacific Entomologist 1925 - 1966. ACIAR Monograph No 27. 120pp. ISBN 1 86320 106 8 Technical editing and production: Arowang Information Bureau Ply Ltd. Canberra Cover: BPD Graphic Associates, Canberra in association with Arawang Information Bureau Ply Lld Printed by The Craftsman Press Ply Ltd. Burwood, Victoria. ACIAR acknowledges the generous support of tihe Paine family in the compilation of this book. Long before agricultural 1920s was already at the Foreword sustainability entered forefront of world biological common parlance, or hazards control activities. Many of the associated with misuse of projects studied by Ron Paine pesticides captured headlines, and his colleagues are touched environmentally friendly on in his delightful and biological control of introduced evocative reminiscences. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

Colonial Administration Records (Migrated Archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021

Colonial administration records (migrated archives): Basutoland (Lesotho) FCO 141/293 to 141/1021 Most of these files date from the late 1940s participation of Basotho soldiers in the Second Constitutional development and politics to the early 1960s, as the British government World War. There is included a large group of considered the future constitution of Basutoland, files concerning the medicine murders/liretlo FCO 141/294-295: Constitutional reform in although there is also some earlier material. Many which occurred in Basutoland during the late Basutoland (1953-59) – of them concern constitutional developments 1940s and 1950s, and their relation to political concerns the development of during the 1950s, including the establishment and administrative change. For research already representative government of a legislative assembly in the late 1950s and undertaken on this area see: Colin Murray and through the establishment of a the legislative election in 1960. Many of the files Peter Sanders, Medicine Murder in Colonial Lesotho legislative assembly. concern constitutional development. There is (Edinburgh UP 2005). also substantial material on the Chief designate FCO 141/318: Basutoland Constitutional Constantine Bereng Seeiso and the role of the http://www.history.ukzn.ac.za/files/sempapers/ Commission; attitude of Basutoland British authorities in his education and their Murray2004.pdf Congress Party (1962); concerns promotion of him as Chief designate. relations with South Africa. The Resident Commisioners of Basutoland from At the same time, the British government 1945 to 1966 were: Charles Arden-Clarke (1942-46), FCO 141/320: Constitutional Review Commission considered the incorporation of Basutoland into Aubrey Thompson (1947-51), Edwin Arrowsmith (1961-1962); discussion of form South Africa, a position which became increasingly (1951-55), Alan Chaplin (1955-61) and Alexander of constitution leading up to less tenable as the Nationalist Party consolidated Giles (1961-66). -

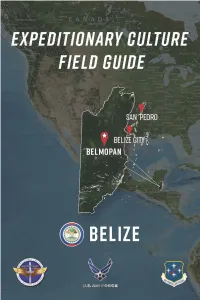

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

Hurricanes and the Forests of Belize, Jon Friesner, 1993. Pdf 218Kb

Hurricanes and the Forests Of Belize Forest Department April 1993 Jon Friesner 1.0 Introduction Belize is situated within the hurricane belt of the tropics. It is periodically subject to hurricanes and tropical storms, particularly during the period June to July (figure 1). This report is presented in three sections. - A list of hurricanes known to have struck Belize. Several lists documenting cyclones passing across Belize have been produced. These have been supplemented where possible from archive material, concentrating on the location and degree of damage as it relates to forestry. - A map of hurricane paths across Belize. This has been produced on the GIS mapping system from data supplied by the National Climatic Data Centre, North Carolina, USA. Some additional sketch maps of hurricane paths were available from archive material. - A general discussion of matters relating to a hurricane prone forest resource. In order to most easily quote sources, and so as not to interfere with the flow of text, references are given as a number in brackets and expanded upon in the reference section. Summary of Hurricanes in Belize This report lists a total of 32 hurricanes. 1.1 On Hurricanes and Cyclones (from C.J.Neumann et al) Any closed circulation, in which the winds rotate anticlockwise in the Northern Hemisphere or clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere, is called a cyclone. Tropical cyclones refer to those circulations which develop over tropical waters, the tropical cyclone basins. The Caribbean Sea is included in the Atlantic tropical cyclone basin, one of six such basins. The others in the Northern Hemisphere are the western North Pacific (where such storms are called Typhoons), the eastern North Pacific and the northern Indian Ocean.