Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

The Effects of Teacher Certification and Experience on Student

THE EFFECTS OF TEACHER CERTIFICATION AND EXPERIENCE ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT ON PRIMARY SCHOOL EXAMINATION IN BELIZEAN PRIMARY SCHOOLS By CARMEN JANE LOPEZ Bachelor of Science in Biology Education University College of Belize Belize City, Belize 1997 Master of Arts in Educational Leadership University of North Florida Jacksonville, Florida 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION July, 2012 THE EFFECTS OF TEACHER CERTIFICATION AND EXPERIENCE ON STUDENT ACHIEVEMENT ON PRIMARY SCHOOL EXAMINATION IN BELIZEAN PRIMARY SCHOOLS Dissertation Approved: Dissertation Adviser’s Dr. Ed Harris Dissertation Adviser Committee Member Dr. Mwarumba Mwavita Committee Member Dr. Stephen Wanger Committee Member Dr. Jesse Mendez Committee Member Dr. Pasha Antonenko Dr. Sheryl A. Tucker Dean of the Graduate College ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................1 History of Teacher Education in Belize ...................................................................3 Problem Statement ...................................................................................................4 Purpose of Study ......................................................................................................5 Research Questions and Hypotheses………………………………………………5 Theoretical Framework ............................................................................................7 -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 18 February 2009 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review Fifth session Geneva, 4-15 May 2009 NATIONAL REPORT SUBMITTED IN ACCORDANCE WITH PARAGRAPH 15 (A) OF THE ANNEX TO HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL RESOLUTION 5/1 * Belize _________________________ * The present document was not edited before being sent to the United Nations translation services. GE.09- A/HRC/WG.6/5/BLZ/1 Page 2 I. INTRODUCTION AND METHODOLOGY 1. Belize is firmly committed to the protection and promotion of human rights as evidenced by its Constitution, domestic legislation, adherence to international treaties and existing national agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). 2. Belizean culture, democratic history and legal tradition has infused in Belizean society and government a deep respect for those fundamental human rights articulated in Part II of the Belize Constitution. Such fundamental freedoms as the right to assembly, the right to free speech and the right to due process are vigilantly guarded by Belizeans themselves. 3. As a developing country Belize views development as inextricably bound to the fulfilment of human rights making the right to development a fundamental right itself as asserted by the Declaration on the Right to Development. Thus, the Government of Belize has consistently adopted a human rights based approach in development planning, social services and general policy formulation and execution. 4. Belize’s national report for the Universal Periodic Review has been prepared in accordance with the General Guidelines for the Preparation of Information under the Universal Periodic Review, decision 6/102, as circulated adopted by the Human Rights Council on 27 September 2007. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

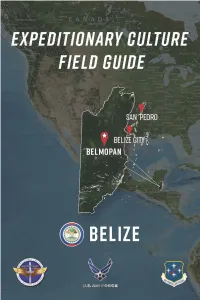

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

In the Supreme Court of Belize, A.D

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF BELIZE, A.D. 2004 ACTION NO. 132 ( MARIA ROCHES Applicant ( ( BETWEEN ( AND ( ( ( CLEMENT WADE ( as and representing the Managing ( Authority of Catholic Public Schools Respondent __ BEFORE the Honourable Abdulai Conteh, Chief Justice. Mr. Dean Barrow S.C. with Mrs. Magali Marin Young for the Applicant. Mr. Philip Zuniga S.C. for the Respondent. __ JUDGMENT The applicant in these proceedings, Ms. Maria Roches, who will be 25 years in May, is a teacher by profession and has taught in Roman Catholic Schools mainly in the Toledo District. She began to teach in 1999, first at the Silver Creek Roman Catholic School, then at the San Pedro Columbia Roman Catholic School and finally at the Santa Cruz Roman Catholic School. It was while a teacher at the latter school that she received a letter dated 26 June 2003 from Mr. Benjamin Juarez, who is the Assistant Local Manager of the Toledo Public Catholic Schools. This letter in effect, Ms. Roches claims, dismissed her from her position as a teacher. 2. This letter is, I think, central to this case. It states as follows: 1 “June 26, 2003 Dear Miss Maria Roches, In view of the fact that you are not complying with the contract you made with the Toledo Catholic Schools Management to live according to Jesus’ teaching on marriage and sex, this management is hereby informing you that you will be released from your duties as a teacher in this management effective August 31st, 2003. Thank you for the services rendered over the past years. -

Education and Training Act Chapter 36:01

BELIZE EDUCATION AND TRAINING ACT CHAPTER 36:01 REVISED EDITION 2011 SHOWING THE SUBSTANTIVE LAWS AS AT 31ST DECEMBER, 2011 This is a revised edition of the Substantive Laws, prepared by the Law Revision Commissioner under the authority of the Law Revision Act, Chapter 3 of the Substantive Laws of Belize, Revised Edition 2011. Education And Training [CAP. 36:01 3 CHAPTER 36:01 EDUCATION AND TRAINING ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I Preliminary 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. PART II Ministry of Education 3. General functions of the Ministry of Education. 4. Appointment of Chief Education Officer. 5. Appointment of other officers and employees. 6. Annual Report. PART III National Council for Education 7. National Council for Education. 8. Composition of the Education Council. THE SUBSTANTIVE LAWS OF BELIZE REVISED EDITION 2011 Printed by Authority of the Government of Belize 4 [CAP. 36:01 Education And Training 9. General functions of the Education Council. 10. Constitution of the Education Council. PART IV National Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training 11. National Council for Technical and Vocational Education and Training. 12. Composition of the TVET Council. 13. General functions of the TVET Council. 14. Constitution of the TVET Council. PART V Belize Teaching Service Commission 15. Belize Teaching Service Commission. 16. Belize Teaching Service Commission Secretariat. 17. Power and functions of the Belize Teaching Service Commission. 18. Constitution of the Commission. THE SUBSTANTIVE LAWS OF BELIZE REVISED EDITION 2011 Printed by Authority of the Government of Belize Education And Training [CAP. 36:01 5 PART VI Teaching Service Appeals Tribunal 19. -

2019 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor: Belize

Belize MODERATE ADVANCEMENT In 2019, Belize made a moderate advancement in efforts to eliminate the worst forms of child labor. The government established a Child Labor Secretariat and Inspectorate to identify, coordinate, and report on child labor cases, and created a program to conduct targeted child labor inspections. During the reporting period, the National Child Labor Committee met regularly and began updating their 2009 National Child Labor Policy by adding additional protections for children. The government also continued to fund a cash assistance program to prevent the commercial sexual exploitation of children. However, children in Belize engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also perform dangerous tasks in agriculture and construction. The country’s minimum age for work is 12 and does not meet international standards. In addition, the country lacks prohibitions against the use of children in illicit activities and does not appear to have programs to address child labor in agriculture, except in the sugar industry. I. PREVALENCE AND SECTORAL DISTRIBUTION OF CHILD LABOR Children in Belize engage in the worst forms of child labor, including in commercial sexual exploitation, sometimes as a result of human trafficking. Children also perform dangerous tasks in agriculture and construction. (1-3) Table 1 provides key indicators on children’s work and education in Belize. Table 1. Statistics on Children’s Work and Figure 1. Working Children by Sector, Education Ages 5-14 Children Age Percent Working (% and population) 5 to 14 1.6 (1,405) Attending School (%) 5 to 14 94.5 Agriculture Combining Work and School (%) 7 to 14 1.2 24.6% Primary Completion Rate (%) N/A 104.5 Source for primary completion rate: Data from 2018, published by UNESCO Services Industry Institute for Statistics, 2020. -

Orthography Development for Creole Languages Decker, Ken

University of Groningen Orthography Development for Creole Languages Decker, Ken IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2014 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Decker, K. (2014). Orthography Development for Creole Languages. [S.n.]. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). The publication may also be distributed here under the terms of Article 25fa of the Dutch Copyright Act, indicated by the “Taverne” license. More information can be found on the University of Groningen website: https://www.rug.nl/library/open-access/self-archiving-pure/taverne- amendment. Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 01-10-2021 ORTHOGRAPHY DEVELOPMENT FOR CREOLE LANGUAGES KENDALL DON DECKER The work in this thesis has been carried out under the auspices of SIL International® in collaboration with the National Kriol Council of Belize. -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

EDUCATION and MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 By

EDUCATION AND MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 by PETER RONALD HITCHEN BA (Hons) History For the award of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE April 2002 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the British neglect of education in Belize and the emergence of increased tensions between church and state, from the twin catalysts for social change of the 1931 hurricane and economic depression until independence in 1981. This conflict has revealed a contradictory web of power structures and their influence, through the medium of schools, on multi-cultural development. The fundamental argument is that despite a rhetoric- of-difference, a cohesive society was created in Belize rooted in the cultural values propagated through an often-contradictory church-state education system, and that Jesuit supremacy of Belizean education came too late to unsettle or exploit the grass-root forces of cultural synthesis. Racial conflict in Belize is more a matter of habitual rhetoric and superficial. The historiography of Belize falls broadly into two categories: Diplomatic and labour, nevertheless cultural and educational studies have developed most notably from Social Anthropology. An extensive literature review revealed that notwithstanding the emergence of a substantial historiography of education on the British Caribbean similar research has been neglected on Belize. Therefore, my own thesis fills a significant gap in the historiography of British Caribbean education. The PhD discusses the relationship between conflicting hierarchies within education and multi-cultural cohesion, not yet been fully attempted in any of the secondary literature. This is a proposition argued through substantial and original primary research, employing a mix of comparative empirical research and theoretical Sights influenced by historical sociologist Nigel Bolland to analyse the interactions of people at community level, the ubiquitous presence of the denominations, and political and hierarchical activities.