Globalization, Tourism and Livelihoods in Placencia, Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Support for the Implementation of the National Sustainable Tourism Master Plan (NSTMP) BL-T1054

Destination Development Plan & Small Scale Investment Project Plan Specific Focus on the Toledo District, Belize 2016 - 2020 Prepared for: Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Table of Tables.............................................................................................................................................. 5 Table of Annexes .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Glossary: ....................................................................................................................................................... 6 FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Executive Summary: ..................................................................................................................................... 8 Introduction: ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Background: ........................................................................................................................................ 10 Community Engagement: .................................................................................................................. -

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

Mangrove Conserva and Preserves Change Adaptation Belize, Central Ame Mangrove Conservation and Preserves As Climate Change Adap

Brooksmith Consulting Mangrove Conservation and Preserves as Climate Change Adaptation in Belize, Central America A case study 6/30/2011 Mangrove Conservation as Climate Change Adaptation in Belize Central America: A Case Study Table of Contents Execut ive Summary 2 Introduction 4 Mangrove conservation and climate change 4 Status of mangrove habitat 5 Climate change in Belize 6 Placencia Village 6 Threats to mangrove habitat 10 Coastal residential development 10 Agriculture and aquaculture 11 A programmatic response to climate change 12 The progression of mangrove conservation activities 13 Mangrove Challenge Contest 16 Mangrove Reserves 21 Bibliography 31 2 Mangrove Conservation as Climate Change Adaptation in Placencia, Belize: A case study Executive Summary The effects of climate change present growing challenges to low-lying developing nations in the Caribbean Basin. Sea level rise, increasing frequency of large tropical cyclones, loss of reef-building corals and other effects are projected to result in direct economic losses consuming over one-fifth of the gross domestic product of nations in the region by 2100. Resilient mangroves shorelines provide multiple buffers against climate change effects. In addition to serving as habitat for marine species and wildlife, mangroves also provide storm protection for coastal communities, a buffer against coastal erosion, carbon sinks, and additional resiliency for economically important habitat such as coral reef. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in Belize has initiated community-based adaptation projects to educate local populations and stakeholders about these emerging problems and to implement “no regrets” adaptation to climate change effects. Understanding of climate change science varies among demographics and opinion leaders within Belize but the value of mangrove habitat for storm protection and fish habitat is generally accepted. -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

Placencia Lagoon Management Plan Management Plan

Placencia Lagoon – Management Plan, 2015-2020 Placencia Lagoon Management Plan Management Plan 2015 – 2020 Wildtracks, 2015 1 Placencia Lagoon – Management Plan, 2015-2020 Acknowledgments We would like to thank Financial support towards this management planning process was provided by the World Wildlife Fund Southern Environmental Association Placencia Village Stann Creek District Belize, Central America Phone: (501) 523-3377 Fax: (501) 523-3395 Email: [email protected] Prepared By: Wildtracks, Belize [email protected] Wildtracks, 2015 2 Placencia Lagoon – Management Plan, 2015-2020 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 Background and Context ......................................................................................................... 5 Purpose and Scope of Plan ....................................................................................................... 7 1. Current Status ......................................................................................................... 8 1.1 Location ............................................................................................................................. 8 1.2 Regional Context .............................................................................................................. 13 1.3 National Context .............................................................................................................. 15 1.3.1 Legal and Policy -

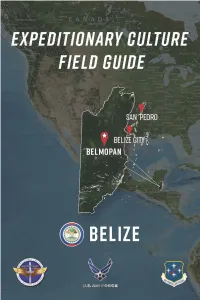

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

EDUCATION and MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 By

EDUCATION AND MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 by PETER RONALD HITCHEN BA (Hons) History For the award of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE April 2002 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the British neglect of education in Belize and the emergence of increased tensions between church and state, from the twin catalysts for social change of the 1931 hurricane and economic depression until independence in 1981. This conflict has revealed a contradictory web of power structures and their influence, through the medium of schools, on multi-cultural development. The fundamental argument is that despite a rhetoric- of-difference, a cohesive society was created in Belize rooted in the cultural values propagated through an often-contradictory church-state education system, and that Jesuit supremacy of Belizean education came too late to unsettle or exploit the grass-root forces of cultural synthesis. Racial conflict in Belize is more a matter of habitual rhetoric and superficial. The historiography of Belize falls broadly into two categories: Diplomatic and labour, nevertheless cultural and educational studies have developed most notably from Social Anthropology. An extensive literature review revealed that notwithstanding the emergence of a substantial historiography of education on the British Caribbean similar research has been neglected on Belize. Therefore, my own thesis fills a significant gap in the historiography of British Caribbean education. The PhD discusses the relationship between conflicting hierarchies within education and multi-cultural cohesion, not yet been fully attempted in any of the secondary literature. This is a proposition argued through substantial and original primary research, employing a mix of comparative empirical research and theoretical Sights influenced by historical sociologist Nigel Bolland to analyse the interactions of people at community level, the ubiquitous presence of the denominations, and political and hierarchical activities. -

Chapter 3 Principles, Materials and Methods Used When Reconstructing

‘Under the shade I flourish’: An environmental history of northern Belize over the last three thousand five hundred years Elizabeth Anne Cecilia Rushton BMus BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ABSTRACT Environmental histories are multi-dimensional accounts of human interaction with the environment over time. They observe how and when the environment changes (material environmental histories), and the effects of human activities upon the environment (political environmental histories). Environmental histories also consider the thoughts and feelings that humans have had towards the environment (cultural/ intellectual environmental histories). Using the methodological framework of environmental history this research, located in sub-tropical northern Belize, brings together palaeoecological records (pollen and charcoal) with archival documentary sources. This has created an interdisciplinary account which considers how the vegetation of northern Belize has changed over the last 3,500 years and, in particular, how forest resources have been used during the British Colonial period (c. AD 1800 – 1950). The palaeoecological records are derived from lake sediment cores extracted from the New River Lagoon, adjacent to the archaeological site of Lamanai. For over 3,000 years Lamanai was a Maya settlement, and then, more recently, the site of two 16th century Spanish churches and a 19th century British sugar mill. The British archival records emanate from a wide variety of sources including: 19th century import and export records, 19th century missionary letters and 19th and 20th century meteorological records and newspaper articles. The integration of these two types of record has established a temporal range of 1500 BC to the present.