Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

Web-Book Catalog 2021-05-10

Lehigh Gap Nature Center Library Book Catalog Title Year Author(s) Publisher Keywords Keywords Catalog No. National Geographic, Washington, 100 best pictures. 2001 National Geogrpahic. Photographs. 779 DC Miller, Jeffrey C., and Daniel H. 100 butterflies and moths : portraits from Belknap Press of Harvard University Butterflies - Costa 2007 Janzen, and Winifred Moths - Costa Rica 595.789097286 th tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA rica Hallwachs. Miller, Jeffery C., and Daniel H. 100 caterpillars : portraits from the Belknap Press of Harvard University Caterpillars - Costa 2006 Janzen, and Winifred 595.781 tropical forests of Costa Rica Press, Cambridge, MA Rica Hallwachs 100 plants to feed the bees : provide a 2016 Lee-Mader, Eric, et al. Storey Publishing, North Adams, MA Bees. Pollination 635.9676 healthy habitat to help pollinators thrive Klots, Alexander B., and Elsie 1001 answers to questions about insects 1961 Grosset & Dunlap, New York, NY Insects 595.7 B. Klots Cruickshank, Allan D., and Dodd, Mead, and Company, New 1001 questions answered about birds 1958 Birds 598 Helen Cruickshank York, NY Currie, Philip J. and Eva B. 101 Questions About Dinosaurs 1996 Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, NY Reptiles Dinosaurs 567.91 Koppelhus Dover Publications, Inc., Mineola, N. 101 Questions About the Seashore 1997 Barlowe, Sy Seashore 577.51 Y. Gardening to attract 101 ways to help birds 2006 Erickson, Laura. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA Birds - Conservation. 639.978 birds. Sharpe, Grant, and Wenonah University of Wisconsin Press, 101 wildflowers of Arcadia National Park 1963 581.769909741 Sharpe Madison, WI 1300 real and fanciful animals : from Animals, Mythical in 1998 Merian, Matthaus Dover Publications, Mineola, NY Animals in art 769.432 seventeenth-century engravings. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

224 Mavis C. Campbell Assad Shoman

224 book reviews Mavis C. Campbell Becoming Belize: A History of an Outpost of Empire Searching for Identity, 1528–1823. Kingston: University of the West Indies Press, 2011. xxii + 425 pp. (Paper US$50.00) Assad Shoman A History of Belize in Thirteen Chapters. 2nd edition. Belize City: The Angelus Press, 2011. xvii + 461 pp. (Paper US$30.00) Modern Belize is commonly referred to as a Caribbean nation in Central Amer- ica. Geographically part of Central America, its English language use and polit- ical history make it part of the Anglophone Caribbean, which may explain in part its relative neglect by scholars of both regions. While Mavis Campbell is not correct to state that Narda Dodson’s A History of Belize (1973) is “the only comprehensive history of Belize written by a trained historian” (p. xiv), she is certainly right to assert that Belizean history “deserves more attention” (p. 4). The enlarged edition of Assad Shoman’s 1994 history is a new contribution aimed at filling the gap. Becoming Belize adds significantly to our understanding of Belize’s begin- nings. Although Campbell did not investigate Spanish primary sources in Ma- drid and Seville, she consulted archives in Belize and Jamaica, at British insti- tutions, and, briefly, in Mérida. The book’s first section examines Spanish at- tempts at settling Belize, from about 1528 to 1708. Campbell explores why Belize became British, given the region’s history, and revisits early Spanish exploration, including Columbus’s 1502 voyage to the Bay Islands of modernity, when he came closest to Belize, and the 1511 shipwreck that left two Spaniards, Gerónimo de Aguilar and Gonzalo Guerrero, in the Yucatán. -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

Geographical and Historical Variation in Hurricanes Across the Yucatán Peninsula

Chapter 27 Geographical and Historical Variation in Hurricanes Across the Yucatán Peninsula Emery R. Boose David R. Foster Audrey Barker Plotkin Brian Hall INTRODUCTION Disturbance is a continual though varying theme in the history of the Yucatán Peninsula. Ancient Maya civilizations cleared and modified much of the forested landscape for millennia, and then abruptly abandoned large areas nearly 1,000 years ago, allowing forests of native species to reestablish and mature (Turner 1974; Hodell, Curtis, and Brenner 1995). More recently, late twentieth century population growth has fueled a resurgence of land-use activity including logging, slash-and-burn agriculture, large mechanized agricultural projects, tourism, and urban expansion (Turner et al. 2001; Turner, Geoghegan, and Foster 2002). Throughout this lengthy history, fires have affected the region—ignited purposefully or accidentally by humans, and occasionally by lightning (Lundell 1940; Snook 1998). And, as indicated by ancient Maya records, historical accounts, and contemporary observations, intense winds associated with hurricanes have repeatedly damaged forests and human settlements (Wilson 1980; Morales 1993). Despite the generally acknowledged importance of natural and human disturbance in the Yucatán Peninsula, there has been little attempt to quantify This research was supported by grants from the National Aeronautics and Space Agency (Land Cover Land-Use Change Program), the National Science Foundation (DEB-9318552, DEB-9411975), and the A. W. Mellon Foundation, and is a contribution from the Harvard Forest Long-Term Ecological Research Program. 495 496 THE LOWLAND MAYA AREA the spatial and temporal distribution of this activity, or to interpret its relationship to modern vegetation patterns (cf. Lundell 1937, 1938; Cairns et al. -

Revista 224.Indd

U CARIBBEAn TROPICAL STORMS Ecological Implications for Pre-Hispanic and Contemporary Maya Subsistence on the Yucatan Peninsula Herman W. Konrad ABSTRACT The ecological stress factor of hurricanes is examined as a dimension of pre-Hispanic Maya adaptation to a tropical forest habitat in the Yucatan peninsula. Pre-Hispanic, colonial and contemporary texts as well as climatic data from the Caribbean region support the thesis that the hurricane was an integral feature of the pre-Hispanic Maya cosmology and ecological paradigm. The author argues that destruction of forests by tropical storms and subsequent succession cycles mimic not only swidden —"slash- and-burn"— agriculture, but also slower, natural succession cycles. With varying degrees of success, flora and fauna adapt to periodic, radical ecosystem disruption in the most frequently hard-hit areas. While not ignoring more widely-discussed issues surrounding the longevity and decline of pre-Hispanic Maya civilization, such as political development, settlement patterns, migration, demographic stability, warfare and trade, the author suggests that effective adaptation to the ecological effects of tropical storms helped determine the success of pre-Hispanic Herman W. Konrad. university Maya subsistence strategies. of Calgary. Email: [email protected] gary.ca NÚMERO 224 • PRIMER TRIMESTRE DE 2003 • 99 Herman W. Konrad RESuMEn Los efectos ecológicos causados por los huracanes se analizan en el contexto de la adaptación de los mayas prehispánicos a la selva de la península de Yucatán. Textos prehispánicos, coloniales y contemporáneos, así como información climática sobre el Caribe en general, apoyan la hipótesis de que el huracán era un elemento central en la cosmovisión y el paradigma ecológico prehispánico. -

Hurricanes of 1955 Gordon E

DECEMBEB1955 MONTHLY WEATHER REVIEW 315 HURRICANES OF 1955 GORDON E. DUNN, WALTER R. DAVIS, AND PAUL L. MOORE Weather Bureau Offrce, Miami, Fla. 1. GENERAL SUMMARY grouping i,n theirpaths. Thethree hurricanes entering the United States all crossed the North Carolina coast There were 13 tropical storms in 1955, (fig. 9), of which within a 6-week period and three more crossed the Mexican 10 attained hurricane force, a number known to have been coast within 150 miles of Tampico within a period of 25 exceeded only once before when 11 hurricanes were re- days. corded in 1950. This compares with a normal of about The hurricane season of 1955 was the most disastrous 9.2 tropical storms and 5 of hurricane intensity. In con- in history and for the second consecutive year broke all trast to 1954, no hurricanes crossed the coastline north of previous records for damage. Hurricane Diane was Cape Hatteras andno hurricane winds were reported north undoubtedly the greatest natural catastrophe in the his- of that point. No tropical storm of hurricane intensity tory of the United Statesand earned the unenviable affected any portion of the United States coastline along distinction of “the first billion dollar hurricane”. While the Gulf of Mexico or in Florida for the second consecutive the WeatherBureau has conservatively estimated the year. Only one hurricane has affected Florida since 1950 direct damage from Diane at between $700,000,000 and and it was of little consequence. However, similar hurri- $800,000,000, indirect losses of wages, business earnings, cane-free periods have occurred before. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

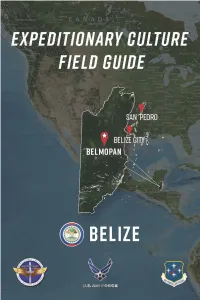

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

By (Under the Direction of Elois Ann Berlin) Knowledge of The

CHILDREN’S ETHNOECOLOGICAL KNOWLEDGE: SITUATED LEARNING AND THE CULTURAL TRANSMISSION OF SUBSISTENCE KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS AMONG Q’EQCHI’ MAYA by REBECCA KRISTYN ZARGER (Under the Direction of Elois Ann Berlin) ABSTRACT Knowledge of the biophysical environment is acquired through participation in cultural routines and immersion in a local human ecosystem. Presented here are the results of a study of the cultural transmission of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) in Q’eqchi’ Maya communities of southern Belize. Qualitative and quantitative methods provided means to describe learning pathways and distribution of subsistence knowledge and skills among children and adults. Data collection focused on situated learning and teaching of TEK during childhood, as very little research of this type exists. Subsistence strategies and local cognitive categories of flora and fauna were documented using methodological approaches from ethnobiology. Food production and preparation, harvesting of herbs, fruits, and medicines, hunting and fishing activities, and construction of household items were included in the domain of subsistence. Systematic behavioral observation, ethnographic interviews, and participant observation provided data about formal and indigenous educational systems. Learning and teaching processes are shaped by cultural belief systems, ecology, socioeconomic institutions, and gender roles. Methods for describing development of expertise in TEK during childhood included pile sorts, freelists, child-guided home garden surveys, and a plant trail in the primary research site. Children develop extensive knowledge early in life. By the time children are 9 years of age, they know 85% of Q’eqchi’ names for plants near the household and 50% of plants elsewhere. Younger children categorize plants based primarily on morphology, and as they gain experience, utility and cultural salience are integrated.