The Meaning of Difference and Women in Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

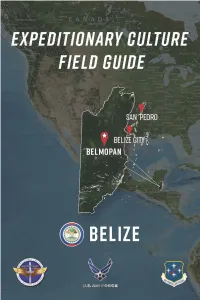

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. -

1 Language Use, Language Change and Innovation In

LANGUAGE USE, LANGUAGE CHANGE AND INNOVATION IN NORTHERN BELIZE CONTACT SPANISH By OSMER EDER BALAM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2016 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the guidance and support from many people, who have been instrumental since the inception of this seminal project on contact Spanish outcomes in Northern Belize. First and foremost, I am thankful to Dr. Mary Montavon and Prof. Usha Lakshmanan, who were of great inspiration to me at Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. Thank you for always believing in me and motivating me to pursue a PhD. This achievement is in many ways also yours, as your educational ideologies have profoundly influenced me as a researcher and educator. I am indebted to my committee members, whose guidance and feedback were integral to this project. In particular, I am thankful to my adviser Dr. Gillian Lord, whose energy and investment in my education and research were vital for the completion of this dissertation. I am also grateful to Dr. Ana de Prada Pérez, whose assistance in the statistical analyses was invaluable to this project. I am thankful to my other committee members, Dr. Benjamin Hebblethwaite, Dr. Ratree Wayland, and Dr. Brent Henderson, for their valuable and insighful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to scholars who have directly or indirectly contributed to or inspired my work in Northern Belize. These researchers include: Usha Lakshmanan, Ad Backus, Jacqueline Toribio, Mark Sebba, Pieter Muysken, Penelope Gardner- Chloros, and Naomi Lapidus Shin. -

EDUCATION and MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 By

EDUCATION AND MULTI CULTURAL COHESION INBELIZE, 1931-1981 by PETER RONALD HITCHEN BA (Hons) History For the award of DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY of the UNIVERSITY OF CENTRAL LANCASHIRE April 2002 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the British neglect of education in Belize and the emergence of increased tensions between church and state, from the twin catalysts for social change of the 1931 hurricane and economic depression until independence in 1981. This conflict has revealed a contradictory web of power structures and their influence, through the medium of schools, on multi-cultural development. The fundamental argument is that despite a rhetoric- of-difference, a cohesive society was created in Belize rooted in the cultural values propagated through an often-contradictory church-state education system, and that Jesuit supremacy of Belizean education came too late to unsettle or exploit the grass-root forces of cultural synthesis. Racial conflict in Belize is more a matter of habitual rhetoric and superficial. The historiography of Belize falls broadly into two categories: Diplomatic and labour, nevertheless cultural and educational studies have developed most notably from Social Anthropology. An extensive literature review revealed that notwithstanding the emergence of a substantial historiography of education on the British Caribbean similar research has been neglected on Belize. Therefore, my own thesis fills a significant gap in the historiography of British Caribbean education. The PhD discusses the relationship between conflicting hierarchies within education and multi-cultural cohesion, not yet been fully attempted in any of the secondary literature. This is a proposition argued through substantial and original primary research, employing a mix of comparative empirical research and theoretical Sights influenced by historical sociologist Nigel Bolland to analyse the interactions of people at community level, the ubiquitous presence of the denominations, and political and hierarchical activities. -

Chapter 3 Principles, Materials and Methods Used When Reconstructing

‘Under the shade I flourish’: An environmental history of northern Belize over the last three thousand five hundred years Elizabeth Anne Cecilia Rushton BMus BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ABSTRACT Environmental histories are multi-dimensional accounts of human interaction with the environment over time. They observe how and when the environment changes (material environmental histories), and the effects of human activities upon the environment (political environmental histories). Environmental histories also consider the thoughts and feelings that humans have had towards the environment (cultural/ intellectual environmental histories). Using the methodological framework of environmental history this research, located in sub-tropical northern Belize, brings together palaeoecological records (pollen and charcoal) with archival documentary sources. This has created an interdisciplinary account which considers how the vegetation of northern Belize has changed over the last 3,500 years and, in particular, how forest resources have been used during the British Colonial period (c. AD 1800 – 1950). The palaeoecological records are derived from lake sediment cores extracted from the New River Lagoon, adjacent to the archaeological site of Lamanai. For over 3,000 years Lamanai was a Maya settlement, and then, more recently, the site of two 16th century Spanish churches and a 19th century British sugar mill. The British archival records emanate from a wide variety of sources including: 19th century import and export records, 19th century missionary letters and 19th and 20th century meteorological records and newspaper articles. The integration of these two types of record has established a temporal range of 1500 BC to the present. -

Globalization, Tourism and Livelihoods in Placencia, Belize

The Belizean Conundrum: Globalization, Tourism and Livelihoods in Placencia, Belize by Myriam Theriault A Practicum Report submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in International Development Studies Saint Mary’s University September, 2007, Halifax, Nova Scotia © Myriam Theriault, 2007 Approved Dr. Anthony O’Malley Supervisor Approved Dr. Henry Veltmeyer Reader Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-35777-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-35777-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce,Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve,sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform,et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. -

Domestic Violence and the Implications For

ABSTRACT WITHIN AND BEYOND THE SCHOOL WALLS: DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOLING by Elizabeth Joan Cardenas Domestic violence complemented by gendered inequalities impact both women and children. Research shows that although domestic violence is a global, prevalent social phenomenon which transcends class, race, and educational levels, this social monster and its impact have been relatively ignored in the realm of schooling. In this study, I problematize the issue of domestic violence by interrogating: How do the family and folk culture educate/miseducate children and adults about their gendered roles and responsibilities? How do schools reinforce the education/miseducation of these gendered roles and responsibilities? What can we learn about the effects of this education/ miseducation? What can schools do differently to bridge the gap between children and families who are exposed to domestic violence? This study introduces CAREPraxis as a possible framework for schools to implement an emancipatory reform. CAREPraxis calls for a re/definition of school leadership, home-school relationship, community involvement, and curriculum in order to improve the deficiency of relationality and criticality skills identified from the data sources on the issue of domestic violence. This study is etiological as well as political and is grounded in critical theory, particularly postcolonial theory and black women’s discourses, to explore the themes of representation, power, resistance, agency and identity. I interviewed six women, between ages 20 and 50, who were living or have lived in abusive relationships for two or more years. The two major questions asked were: What was it like when you were growing up? What have been your experiences with your intimate male partner with whom you live/lived. -

Proquest Dissertations

The political ecology of peasant sugarcane farming in northern Belize Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Higgins, John Erwin, 1954- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 00:01:29 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/288803 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text direcdy from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter &ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely a£fect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. -

Incarnation of the National Identity Or Ethnic Affirmation ? Creoles of Belize

Chapter 2 Incarnation of the National Identity or Ethnic Affirmation? Creoles of Belize1 Elisabeth Cunin xyx h wahn no who seh Kriol no gat no kolcha” (“I want to know who said Creoles have no culture”). The title of this“A song by Lee Laa Vernon, famous Belizean artist, reveals the current transformations of the “Creole” status in this small Anglophone country of Central America. Until now, because it was considered the symbol of Belize, the “Creole culture” did not need to be defined, much less defended. This culture was considered to be precisely what bound together a society that was characterized by a multiplicity of groups, described in accordance with their specific origin, history, culture and language. This society was frequently shown as multiethnic, in which the Creoles were the guarantors of integration and “ethnic” labels were reserved for the rest, the “others.” Creoles recognized themselves better in their close relationship with power, symbolized by the British Crown and its representa- tives, colonial administrators and major traders, in a territory that was British Honduras for a long time. Does the fact that Blackness and mestizaje in Mexico and Central America Creoles wonder about their own culture now mean they have to be understood as an ethnic group just like the others? In the way this ethnicity is asserted, are the aspirations of the Creoles to embody the nation, in the way they are considered to have embodied the colony, thereby weakened? Being the dominant group, the Creoles did not define them- selves as an ethnic group; they reserved this label for the “others,” those who were not thought to incarnate the Colony, and then the Nation; those who, quoting the expression of Cedric Grant (1976, 19), are in the society, but are not from this society.