Incarnation of the National Identity Or Ethnic Affirmation ? Creoles of Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize National Sustainable Development Report

UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report Belize National Sustainable Development Report Ministry of Forestry, Fisheries, and Sustainable Development, Belize United Nations Department of Social and Economic Affairs (UNDESA) United Nations Development Program (UNDP) ____________________________________ INSTITUTIONAL DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS – www.idcbz.net Page | 1 UNCSD – Belize National Sustainable Development Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Acronyms Acknowledgements 1.0. Belize Context……………………………………………………………………………………5 1.1 Geographical Location………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Climate………………………………………………………………………………………..5 1.3 Hydrology……………………………………………………………………………………..6 1.4 Population…………………………………………………………………………………….6 1.5 Political Context……………………………………………………………………………...7 1.6 Economy……………………………………………………………………………………...7 2.0 Background and Approach………………………………………………………………………….7 3.0 Policy and Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development………………………………8 3.1 National Level………………………………………………………………………………..8 3.2 Multi-Lateral Agreements…………………………………………………………………...9 4.0 Progress to Date in Sustainable Development…………………………………………………..10 5.0 Challenges to Sustainable Development…………………………………………………………23 5.1 Environmental and Social Vulnerabilities………………………………………………..23 5.2 Natural Disasters…………………………………………………………………………...23 5.3 Climate Change…………………………………………………………………………….23 5.4 Economic Vulnerability…………………………………………………………………….24 5.5 Policy and Institutional Challenges……………………………………………………….24 6.0 Opportunities for Sustainable Development……………………………………………………..26 -

A Study of the Garifuna of Belize's Toledo District Alexander Gough

Indigenous identity in a contested land: A study of the Garifuna of Belize’s Toledo district Alexander Gough This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2018 Lancaster University Law School 1 Declaration This thesis has not been submitted in support of an application for another degree at this or any other university. It is the result of my own work and includes nothing that is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated. Many of the ideas in this thesis were the product of discussion with my supervisors. Alexander Gough, Lancaster University 21st September 2018 2 Abstract The past fifty years has seen a significant shift in the recognition of indigenous peoples within international law. Once conceptualised as the antithesis to European identity, which in turn facilitated colonial ambitions, the recognition of indigenous identity and responding to indigenous peoples’ demands is now a well-established norm within the international legal system. Furthermore, the recognition of this identity can lead to benefits, such as a stake in controlling valuable resources. However, gaining tangible indigenous recognition remains inherently complex. A key reason for this complexity is that gaining successful recognition as being indigenous is highly dependent upon specific regional, national and local circumstances. Belize is an example of a State whose colonial and post-colonial geographies continue to collide, most notably in its southernmost Toledo district. Aside from remaining the subject of a continued territorial claim from the Republic of Guatemala, in recent years Toledo has also been the battleground for the globally renowned indigenous Maya land rights case. -

“I'm Not a Bloody Pop Star!”

Andy Palacio (in white) and the Garifuna Collective onstage in Dangriga, Belize, last November, and with admirers (below) the voice of thPHOTOGRAPHYe p BYe ZACH oSTOVALLple BY DAVE HERNDON Andy Palacio was more than a world-music star. “I’m not a bloody pop star!” He was a cultural hero who insisted Andy Palacio after an outdoor gig in Hopkins, Belize, that revived the hopes of a was so incendiary, a sudden rainstorm only added sizzle. But if it Caribbean people whose was true that Palacio wasn’t a pop star, you couldn’t tell it from the heritage was slipping away. royal treatment he got everywhere he went last November upon 80 CARIBBEANTRAVELMAG.COM APRIL 2008 81 THE EVENTS OF THAT NOVEMBER TOUR WILL HAVE TO GO DOWN AS PALACIO’S LAST LAP, AND FOR ALL WHO WITNESSED ANY PART OF IT, THE STUFF OF HIS LEGEND. Palacio with his role model, the singer and spirit healer Paul Nabor, at Nabor’s home in Punta Gorda (left). The women of Barranco celebrated with their favorite son on the day he was named a UNESCO Artist for Peace (below left and right). for me as an artist, and for the Belizean people which had not been seen before in those parts. There was no as an audience.” The Minister of Tourism Belizean roots music scene or industry besides what they them- thanked Palacio for putting Belize on the map selves had generated over more than a dozen years of collabora- in Europe, UNESCO named him an Artist tion. To make Watina, they started with traditional themes and for Peace, and the Garifuna celebrated him motifs and added songcraft, contemporary production values as their world champion. -

Educating Belize: Challenges and Opportunities for the Future

The University of Texas at Austin IC2 Institute Madison Weigand Dr. David Gibson UT Bridging Disciplines http://ic2.utexas.edu/ z EDUCATING BELIZE: CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE FUTURE August 2015 BELIZE IC2 2 “Belize is paying a lot for education but getting little. More youth are outside the school system than in it and many fail to make the transition to the workforce. … Action is needed if Belize is not to lose a whole generation of youth.” - Inter-American Development Bank, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Belize Education Sector”, 2013 Belize: why we’re here Belize is a small nation in Central America, bordered to the north by Mexico, by Guatemala to the west and south, and by the Caribbean Sea to the east. Estimates of the national population vary from 340,000 – 360,0001, with population density averaging at 15 people per square kilometer2. In consideration of these low figures, Belize is often the forgotten nation of the Caribbean region. The small country, approximately the size of the state of Massachusetts, is occasionally omitted on regional maps and periodically has its sovereignty threatened by threats of invasion from the neighboring Guatemalan government (Rodriguez-Boetsch 6). In spite of its status as a sidelined nation, Belize is a haven of natural resources that have long been underestimated and underutilized. The country contains a broad spectrum of ecosystems and environments that lend themselves well to agricultural, fishing, and logging industries, as well as tourism—particularly ecotourism—contributing to the Belizean economy’s heavy dependence upon primary resource extraction and international tourism and trade. -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

Lopez Niu 0162D 12061.Pdf (3.188Mb)

ABSTRACT BECOMING WHO WE ARE: INFORMAL LEARNING AND IDENTITY FORMATION AMONG THE GARINAGU OF WESTERN BELIZE Harold Anthony Lopez, Ed.D. Department of Counseling, Adult, and Higher Education Northern Illinois University, 2014 Gene Roth and Jorge Jeria, Co-Directors This ethnography explores the wholesome contexts of informal learning and identity formation among an ethnic minority group in Belize. The central research question of the study was: How is informal learning manifested among the Garinagu of Western Belize. Snowball sampling technique was used to recruit 20 participants aged between 36 and 82 years. The group’s ways of learning were examined through the lens of Sociocultural learning theory. In the conduct of the maintenance of culture, learning is centered on their resiliency as examined through the various experiences that they acquired as a result of their movements, disruption and setbacks, the concept of Garifunaduaü, the meet and greet process, and the roles of rituals and ancestry. The Garinagu display remarkable resiliency in their quest to maintain their cultural identity. Their resiliency is demonstrated through the ways in which they navigate their world that constantly changes through the many moves, disruptions and setbacks that they experience and share. Garifunaduaü pays homage to the principles of caring, daring, sharing and family. Rituals and ancestry provides for connection and continuity. Connection with traditional Garifuna communities as maintained through regular or extended visits to traditional communities helped participants retain key cultural habits and artifacts including fluency in the Garifuna language, participation in the rituals, and regular preparation of traditional foods. Smaller family sizes and a shrinking of the extended family are threatening cultural practice. -

The Case for a Belizean Pan-Africanism

The Case for a Belizean Pan-Africanism by Kurt B. Young, Ph.D. Assistant Professor, Political Science & African American Studies University of Central Florida, Orlando, Florida [email protected] Abstract This essay is an analysis of Pan-Africanism in the Central American country of Belize. One of the many significant products of W.E.B. DuBois’s now famous utterance that “The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line” has been the unending commitment to document the reality of the color line throughout the various regions of the African Diaspora. Thus, nearly a century after his speech at the First Pan-African Congress, this effort has produced a corpus of works on Pan-Africanism that capture the global dimensions of the Pan- African Movement. However, the literature on Pan-Africanism since has been and remains fixed on the Caribbean Islands, North America and most certainly Africa. This tendency is justifiable given the famous contributions of the many Pan-African freedom fighters and the formations hailing from these regions. But this has been at a cost. There remains significant portions of the African Diaspora whose place in and contributions to the advancement of Pan-Africanism has been glossed over or fully neglected. The subject of this paper is to introduce Belize as one of the neglected yet prolific fronts in the Pan-African phenomenon. Thus this essay utilizes a Pan- African nationalist theoretical framework that captures the place of Belize in the African Diaspora, with an emphasis on 1) identifying elements of Pan-Africanism based on a redefinition of the concept and 2) applying them in a way that illustrates the Pan-African tradition in Belize. -

Download PDF File

Friday, May 21, 2021 AMANDALABelize Page 1 NO. 3462 BELIZE CITY, FRIDAY, MAY 21, 2021 (36 PAGES) $1.50 Borders Gruesome daylight opened for city murder tourists only BELIZE CITY, Thurs. May of less than 24 hours. Last night, 20, 2021 Marquin Drury was fatally wounded At high noon today, a 19- in a drive-by shooting. year-old was shot multiple Unconfirmed reports are that times and left for dead in the Castillo was pursued by his assailant, Fabers Road Extension area. then executed in cold blood near a Stephan Castillo, the mechanic shop on Fabers Road, not victim of this most recent far from the police sub-station in that Belize City murder, is the area. second person to be shot to death in the city within a span Please turn toPage 29 Unions stage funeral procession for corruption BELIZE CITY, Wed. May 19, 2021 On Tuesday, May 18, members of the Belize National Teachers Union (BNTU) and the Public Service Union (PSU) staged mock funeral BELIZE CITY, Thurs. May 20, 2021 processions — a symbolic form of Today Cabinet released an update protest that is a marked departure on matters that were discussed and from the blockades that had been set decisions that were made during its up on the previous day to prevent the regular session meeting, which took flow of traffic on roads and highways place on May 18, 2021. In that press countrywide. They marched along the release, the public was informed that streets, carrying a coffin, as they pretended to engage in funeral rites Please turn toPage 30 Please turn toPage 31 PM replies PGIA employees Belize seeks extension to unions stage walkout for bond payment BELIZE CITY. -

Anthropology / Anthropologie/ Antropología

Bibliographical collection on the garifuna people The word garifuna comes from Karina in Arawak language which means “yucca eaters”. ANTHROPOLOGY / ANTHROPOLOGIE/ ANTROPOLOGÍA Acosta Saignes, Miguel (1950). Tlacaxipeualiztli, Un Complejo Mesoamericano Entre los Caribes. Caracas: Instituto de Antropología y Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Central. Adams, Richard N. (1956). «Cultural Components of Central America». American Anthropologist, 58, 881- 907. Adams, Sharon Wilcox (2001). The Garifuna of Belize: Strategies of Representation. B.A. Honors Thesis, Mary Washington College. Adams, Sharon Wilcox (2006). Reconstructing Identity: Representational Strategies in the Garifuna Community of Dangriga, Belize. M. A. Thesis, University of Texas, Austin. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). “Qu’est-ce qui vient après la reconnaissance ? Multiculturalisme et populations noires en Amérique latine» in Christian Gros et David Dumoulin Kervran (eds.) Le multiculturalisme au concret. Un modèle latino américain?. Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, pp. 267-277. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). «The afro-guatemalan Political Mobilization: Between Identity, Construction Process, Global Influences and Institutionalization» in Jean Rahier (ed) Black Social Movements in Latin America. From Monocultural Mestizaje to Multiculturalism. Miami: Palgrave Macmillan. Agudelo, Carlos (2012). “Los garifunas, identidades y reivindicaciones de un pueblo afrodescendiente de América Central” in CINU-Centro de información de las Naciones Unidas (ed.) Afrodescendencia: aproximaciones contemporáneas desde América Latina y el Caribe, pp. 59-66. http://www.cinu.mx/AFRODESCENDENCIA.pdf viewed 06.04.2012. Agudelo, Carlos (2010). “Génesis de redes transnacionales. Movimientos afrolatinoamericanos en América Central» in Odile Hoffmann (ed.) Política e Identidad. Afrodescendientes en México y América Central. México: INAH, UNAM, CEMCA, IRD, pp. 65-92. Agudelo, Carlos (2011). “Les Garifuna. -

“We Are Strong Women”: a Focused Ethnography Of

“WE ARE STRONG WOMEN”: A FOCUSED ETHNOGRAPHY OF THE REPRODUCTIVE LIVES OF WOMEN IN BELIZE Carrie S. Klima, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2002 Belize is a small country in Central America with a unique heritage. The cultural pluralism found in Belize provides an opportunity to explore the cultures of the Maya, Mestizo and the Caribbean. Women in Belize share this cultural heritage as well as the reproductive health issues common to women throughout the developing world. The experiences of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use and abortion were explored with women using a feminist ethnographic framework. Key informants, participant observations, secondary data sources and individual interviews provided rich sources of data to examine the impact of culture in Belize upon the reproductive lives of women. Data were collected over a two-year period and analyzed using QSRNudist qualitative data analysis software. Analysis revealed that regardless of age, ethnicity or educational background, women who found themselves pregnant prior to marriage experienced marriage as a fundamental cultural norm in Belize. Adolescent pregnancy often resulted in girls’ expulsion from school and an inability to continue with educational goals. Within marriage, unintended pregnancy was accepted but often resulted in more committed use of contraception. All women had some knowledge and experience with contraception, Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Carrie S. Klima-University of Connecticut, 2002 although some were more successful than others in planning their families. Couples usually made decisions together regarding when to use contraception, however misinformation regarding safety and efficacy was prevalent. While abortion is illegal, most women had knowledge of abortion practices and some had personal experiences with self induced abortions using traditional healing practices common in Belize. -

Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize

DEBORAH L. CROOKS / UNIVERSITY OF KENTUCKY Biocultural Factors in School Achievement for Mopan Children in Belize We were once much smarter people. into traditional statistical models of biological anthro- —Maya caretaker at archaeological site, Toledo District, Belize pological research is difficult because of the distinctly different nature of the two kinds of data produced. One MOPAN MAYA CHILDREN of San Antonio, Toledo, Be- approach to this problem is discussed by William lize, face a number of challenges to their success in Dressier (1995), who advocates using ethnography up school. Mayan ethnicity, language, and traditional eco- front in the research design to construct culturally nomic strategies are rendered disadvantageous for meaningful variables that can then be quantified for school achievement by historical, social, cultural, and testing. Resulting models are able to account for local economic forces. Statistics on poverty and child growth levels of meaning within the framework of "scientific" indicate that Mayan children are poorer and more research. poorly nourished than other Belizean children, and they Another approach is that taken by Thomas Leather- do less well on national achievement exams. In addi- man (in press) and Brooke Thomas (in press). This po- tion, they attend school structured on the British model litical-economic approach uses quantitative measures and taught in English. In the past, biocultural ap- of biological outcome but contextualizes the numbers proaches might model a causal pathway from poverty to by focusing "upstream" on conditions that produce nutritional status to cognitive development to school stress and either facilitate or constrain coping re- achievement. But the interrelationships among poverty, sponses. -

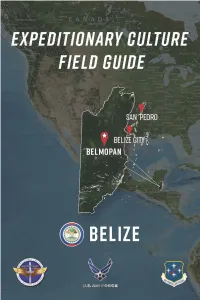

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.