State of the Belize Coastal Zone Report 2003–2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Belize Factsheet IV – Maritime and Coastal Tourism

Evidence-based and policy coherent Oceans Economy and Trade Strategies1. Sector data factsheet2: Belize Maritime and coastal tourism 1. INTRODUCTION The project “Evidence-based and policy coherent Oceans Economy and Trade Strategies” aims to support developing countries such as Barbados, Belize and Costa Rica, in realizing trade and economic benefits from the sustainable use of marine resources within the framework of the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This data factsheet presents detailed sectorial information of one (of the four) ocean sectors selected in Belize to facilitate the identification and informed selection of key sectors to be considered for the next phase of the project: Sector 1 Sector 2 Sector 3 Sector 4 Marine fisheries Aquaculture Seafood manufacturing Tourism 1.1. THE MARITIME TOURISM SECTOR Tourism is the largest of all ocean economic sectors, generating more than a USD 1.6 trillion globally in 2017. International tourist arrivals grew by 7% reaching a record of 1,323 million arrivals in 2017. It is expected that international arrivals will reach to 1.8 trillion by 2030 (UNWTO, 2018), outperforming all other services sectors with perhaps the exception of financial services. Tourism is also the sector that contributes the most to the GDP of Small Island Developing States (SIDS), but also of coastal developing countries. These countries enjoy a special geographical situation, outstanding natural endowments and cultural heritage richness that make them unique for visitors. At the same time, they confront several challenges and vulnerabilities including remoteness, low connectivity, limited economic diversification, small internal markets, as well as adverse, perhaps recurrent climate events. -

International Narcotics Control Strategy Report

United States Department of State Bureau for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs International Narcotics Control Strategy Report Volume I Drug and Chemical Control March 2017 INCSR 2017 Volume 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents Common Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. iii International Agreements .......................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................... 1 Policy and Program Developments ......................................................................................................... 17 Overview ................................................................................................................................................. 18 Methodology for U.S. Government Estimates of Illegal Drug Production ............................................... 24 (with dates ratified/acceded) ................................................................................................................... 30 USG Assistance ..................................................................................................................................... 36 International Training ............................................................................................................................. -

Belize), and Distribution in Yucatan

University of Neuchâtel, Switzerland Institut of Zoology Ecology of the Black Catbird, Melanoptila glabrirostris, at Shipstern Nature Reserve (Belize), and distribution in Yucatan. J.Laesser Annick Morgenthaler May 2003 Master thesis supervised by Prof. Claude Mermod and Dr. Louis-Félix Bersier CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1. Aim and description of the study 2. Geographic setting 2.1. Yucatan peninsula 2.2. Belize 2.3. Shipstern Nature Reserve 2.3.1. History and previous studies 2.3.2. Climate 2.3.3. Geology and soils 2.3.4. Vegetation 2.3.5. Fauna 3. The Black Catbird 3.1. Taxonomy 3.2. Description 3.3. Breeding 3.4. Ecology and biology 3.5. Distribution and threats 3.6. Current protection measures FIRST PART: BIOLOGY, HABITAT AND DENSITY AT SHIPSTERN 4. Materials and methods 4.1. Census 4.1.1. Territory mapping 4.1.2. Transect point-count 4.2. Sizing and ringing 4.3. Nest survey (from hide) 5. Results 5.1. Biology 5.1.1. Morphometry 5.1.2. Nesting 5.1.3. Diet 5.1.4. Competition and predation 5.2. Habitat use and population density 5.2.1. Population density 5.2.2. Habitat use 5.2.3. Banded individuals monitoring 5.2.4. Distribution through the Reserve 6. Discussion 6.1. Biology 6.2. Habitat use and population density SECOND PART: DISTRIBUTION AND HABITATS THROUGHOUT THE RANGE 7. Materials and methods 7.1. Data collection 7.2. Visit to others sites 8. Results 8.1. Data compilation 8.2. Visited places 8.2.1. Corozalito (south of Shipstern lagoon) 8.2.2. -

Baseline Assessment Study on Wastewater Management Belize

Caribbean Regional Fund for Wastewater Management Baseline Assessment Study on Wastewater Management Belize December 2013 Revised January 2015 Baseline Assessment Study for the GEF CReW Project: Belize December 2013 Prepared by Dr. Homero Silva Revised January 2015 CONTENTS List of Acronyms....................................................................................................................................................iii 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 2. The National Context ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Description of the Country .................................................................................................................. 4 Geographic Characteristics ................................................................................................................. 6 Economy by Sectors ............................................................................................................................ 9 The Environment .............................................................................................................................. 13 Land Use, Land Use Changes and Forestry (LULUCF) ....................................................................... 20 Disasters .......................................................................................................................................... -

El Salvador Belize Population Estimate: 377,968 Surface Area: 8,867 Sq

Kim Bautista Vector Control Chief of Operations RCM Meeting 29– 31 May 2018, San Salvador – El Salvador Belize Population Estimate: 377,968 Surface Area: 8,867 sq. miles/ 22,966 sq. km 6 administrative divisions (districts) Vector Control • Dengue, Zika, Chikungunya, Chagas, Malaria • 62 personnel Malaria 10 Year Trend 2017 Malaria 2017 Malaria by District and Species District SPECIES FALCIP VIVAX MIXED Total Corozal 0 0 0 0 Orange Walk 0 0 0 0 Belize 1 1 0 2 Cayo 0 1 0 1 Stann Creek 0 4 2 6 Toledo 0 0 0 0 Total 1 6 2 9 2018 Malaria Cases 2018 Imported Cases Stann Creek District – • 1 case – Peten, Guatemala • 1 case – Managua, Nicaragua Belize District – • 1 case – Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua • 1 case – Paramaribo, Suriname 2018 Local Cases • NONE Current Malaria Situation Priority Locations (2018) District Population Status Active and Residual Non-Active Foci Benque Viejo Del Carmen Town Cayo District 6780 Active Corozal Town Corozal District 12334 Residual Non-Active Patchakan Village Corozal District 1506 Residual Non-Active San Pedro Vilage Corozal District 596 Residual Non-Active San Victor Village Corozal District 938 Residual Non-Active San Estevan Village Orange Walk District 1821 Residual Non-Active San Jose Orange Village Orange Walk District 2800 Residual Non-Active Silk Grass Village Stann Creek District 1096 Active Conejo Village Toledo District 161 Residual Non-Active Trio Village Toledo District 1521 Active • Active Foci – 3 • Residual Non-Active - 7 Current Malaria Situation • The primary target areas are villages in the -

2-1 CHAPTER 2 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 2.1 Topography

CHAPTER 2 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 2.1 Topography The general topography of the area is essentially a hilly terrain with lots of tributaries meandering throughout the landscape of the Spanish Lookout Area. The higher altitudes of the terrain are found more northwards of the Spanish Lookout Area with elevations reaching the 280 meters above mean sea level (MSL). This area is also known as the Yalbac Hills. This ridge extends in a semicircular direction towards the northwestern portion of the Spanish Lookout area. The lower areas of Spanish Lookout are formed by the creeks and its tributaries that have carved the mountainous terrain as a result of surface runoffs. The Belize River, which meanders in the area, captures the surface water runoffs. The proposed San Marcos development wells will be located on a hilly ridge formed by the undulating landscape. These rolling ridges undulate right through the country side and decreases towards the Iguana Creek’s tributaries. The higher elevation of the area is found just north of the proposed site and this ridge gradually decreases towards the northeast. The topographical contour of the area is about 80 meters above mean sea level (MSL), see figure 2.1. As for the proposed Spanish Lookout wells, they are also located on an elevated ridge carved out by the numerous tributaries of the area. The proposed sites are on a hilly crest that extends northwards and gently slopes downwards towards the south eventually extending to the river. The contouring of the area is about 80 meters above mean sea level (MSL).The gradual cultivation of the land, loss of vegetation and community development has slowly eroded the topography of the Spanish Lookout area. -

Mangrove Conserva and Preserves Change Adaptation Belize, Central Ame Mangrove Conservation and Preserves As Climate Change Adap

Brooksmith Consulting Mangrove Conservation and Preserves as Climate Change Adaptation in Belize, Central America A case study 6/30/2011 Mangrove Conservation as Climate Change Adaptation in Belize Central America: A Case Study Table of Contents Execut ive Summary 2 Introduction 4 Mangrove conservation and climate change 4 Status of mangrove habitat 5 Climate change in Belize 6 Placencia Village 6 Threats to mangrove habitat 10 Coastal residential development 10 Agriculture and aquaculture 11 A programmatic response to climate change 12 The progression of mangrove conservation activities 13 Mangrove Challenge Contest 16 Mangrove Reserves 21 Bibliography 31 2 Mangrove Conservation as Climate Change Adaptation in Placencia, Belize: A case study Executive Summary The effects of climate change present growing challenges to low-lying developing nations in the Caribbean Basin. Sea level rise, increasing frequency of large tropical cyclones, loss of reef-building corals and other effects are projected to result in direct economic losses consuming over one-fifth of the gross domestic product of nations in the region by 2100. Resilient mangroves shorelines provide multiple buffers against climate change effects. In addition to serving as habitat for marine species and wildlife, mangroves also provide storm protection for coastal communities, a buffer against coastal erosion, carbon sinks, and additional resiliency for economically important habitat such as coral reef. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) in Belize has initiated community-based adaptation projects to educate local populations and stakeholders about these emerging problems and to implement “no regrets” adaptation to climate change effects. Understanding of climate change science varies among demographics and opinion leaders within Belize but the value of mangrove habitat for storm protection and fish habitat is generally accepted. -

Hol Chan Marine Reserve Belize

UNITED NATIONS EP United Nations Original: ENGLISH Environment Program Proposed areas for inclusion in the SPAW list ANNOTATED FORMAT FOR PRESENTATION REPORT FOR: Hol Chan Marine Reserve Belize Date when making the proposal : October 5th, 2010 CRITERIA SATISFIED : Ecological criteria Cultural and socio-economic criteria Representativeness Cultural and traditional use Conservation value Critical habitats Area name: Hol Chan Marine Reserve Country: Belize Contacts Last name: BELIZE First name: Belize MPA Focal Point Position: Focal point Email: [email protected] Phone: 0478000000 Last name: ALAMILLA First name: Miguel Manager Position: Manager Email: [email protected] Phone: 501 226 2247 SUMMARY Chapter 1 - IDENTIFICATION Chapter 2 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Chapter 3 - SITE DESCRIPTION Chapter 4 - ECOLOGICAL CRITERIA Chapter 5 - CULTURAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC CRITERIA Chapter 6 - MANAGEMENT Chapter 7 - MONITORING AND EVALUATION Chapter 8 - STAKEHOLDERS Chapter 9 - IMPLEMENTATION MECHANISM Chapter 10 - OTHER RELEVANT INFORMATION ANNEXED DOCUMENTS Chapter 1. IDENTIFICATION a - Country: Belize b - Name of the area: Hol Chan Marine Reserve c - Administrative region: Belize District d - Date of establishment: 7/1/87 e - If different, date of legal declaration: not specified f - Geographic location Longitude X: -88.020058 Latitude Y: 17.875184 g - Size: 55 sq. km h - Contacts Contact adress: Caribena Street - San Pedro Town - Belize Website: http://www.fisheries.gov.bz/ Email address: [email protected] i - Marine ecoregion 68. Western Caribbean Comment, optional none Chapter 2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Present briefly the proposed area and its principal characteristics, and specify the objectives that motivated its creation : The Hol Chan Marine Reserve (HCMR) was established in 1987 to conserve a small but representative portion of Belize's coastal ecosystem. -

302232 Travelguide

302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.1> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 INTRODUCTION 5 WELCOME 6 GENERAL VISITOR INFORMATION 8 GETTING TO BELIZE 9 TRAVELING WITHIN BELIZE 10 CALENDAR OF EVENTS 14 CRUISE PASSENGER ADVENTURES Half Day Cultural and Historical Tours Full Day Adventure Tours 16 SUGGESTED OVERNIGHT ADVENTURES Four-Day Itinerary Five-Day Itinerary Six-Day Itinerary Seven-Day Itinerary 25 ISLANDS, BEACHES AND REEF 32 MAYA CITIES AND MYSTIC CAVES 42 PEOPLE AND CULTURE 50 SPECIAL INTERESTS 57 NORTHERN BELIZE 65 NORTH ISLANDS 71 CENTRAL COAST 77 WESTERN BELIZE 87 SOUTHEAST COAST 93 SOUTHERN BELIZE 99 BELIZE REEF 104 HOTEL DIRECTORY 120 TOUR GUIDE DIRECTORY 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.2> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 302232 TRAVELGUIDE <P.3> (118*205) G5-15 DANIEL V2 The variety of activities is matched by the variety of our people. You will meet Belizeans from many cultural traditions: Mestizo, Creole, Maya and Garifuna. You can sample their varied cuisines and enjoy their music and Belize is one of the few unspoiled places left on Earth, their company. and has something to appeal to everyone. It offers rainforests, ancient Maya cities, tropical islands and the Since we are a small country you will be able to travel longest barrier reef in the Western Hemisphere. from East to West in just two hours. Or from North to South in only a little over that time. Imagine... your Visit our rainforest to see exotic plants, animals and birds, possible destinations are so accessible that you will get climb to the top of temples where the Maya celebrated the most out of your valuable vacation time. -

The Experience of Three Local Ngos in Marine

NEGOTIATING INFLUENCE: THE EXPERIENCE OE THREE LOCAL NCOS IN MARINE RESERVE CO MANAGEMENT IN SOUTHERN BELIZE by Jocelyn Rae Finch B. A. George Washington University 2002 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana May 2006 Approved by: Chairperson: Dean, Graduate School: Date: Finch, Jocelyn Rae M.S. May 2006 Forestry NEGOTIATING INFLUENCE: THE EXPERIENCE OE THREE LOCAL NCOS IN MARINE RESERVE CO-MANAGEMENT IN SOUTHERN BELIZE Chairperson: Dr. Steve Siebert Abstract Co- management has become an important tool in the management of Belize’s natural resources, including the world’s second largest barrier reef. There are many systems for co management.- Delegated co management,- where local NGOs serve as the decision making authority and community representative, is the most popular form for marine reserves in Belize. The use of co management offers a way to engage a diverse range of stakeholders in the decision making process. However, the success of marine reserve co management- is affected by a range of local, national and intemational factors. Through personal observations as a Peace Corps Volunteer working in southem Belize, interviews with key individuals involved in marine co management- and review of related literature, I explore how political and economic issues at the local, national and intemational level have influenced marine reserve co -management. Three Belizean non - govemmental organizations have signed co management- agreements with the Department of Fisheries for the management of marine reserves in southem Belize. My research indicates that there are a number of factors which influence co- management in this situation. -

Chetumal Bay, Mexico ______

_____________________________________________________________________________ Cross Sectoral Initiatives in Democracy and Environment: Chetumal Bay, Mexico _____________________________________________________________________________ Rubinoff, P., R. Romero, and O. Chavez 2001 Citation: Narragansett, Rhode Island USA, Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island InterCoast Newsletter 40 For more information contact: Pamela Rubinoff, Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island. 220 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, RI 02882 Telephone: 401.874.6224 Fax: 401.789.4670 Email: [email protected] This five year project aims to conserve critical coastal resources in Mexico by building capacity of NGOs, Universities, communities and other key public and private stakeholders to promote an integrated approach to participatory coastal management and enhanced decision-making. This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Office of Environment and Natural Resources Bureau for Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. PCE-A-00-95-0030-05. Cross Sectoral Initiatives in Democracy and Environment:Chetumal Bay, Mexico By Pamela Rubinoff, Rafael Romero, and Octavio grated management initiative in Chetumal Bay.” One of the key Chavez goals was to have a well-attended meeting (later called the he environment/democracy linkage has recently been initiat- Chetumal Bay Summit) of key stakeholders to discuss the -

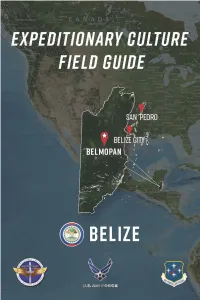

ECFG-Belize-2020R.Pdf

ECFG: Central America Central ECFG: About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: US Marine shows members of Belize Defense Force how to load ammunition into weapons). The guide consists of 2 E parts: CFG Part 1 “Culture General” provides the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment with a focus on Central America (CENTAM). Part 2 “Culture Specific” describes unique cultural features of Belize Belizean society. It applies culture-general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location. This section is designed to complement other pre- deployment training (Photo: USAF medic checks a Belizean patient’s vision during a medical readiness event). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact the AFCLC Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the express permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments.