Baseline Assessment Study on Wastewater Management Belize

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title of the Project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at Selected Water Bodies of Murshidabad District

REPORT ON THE PROJECT 2020 Title of the project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at selected water bodies of Murshidabad district Submitted by Santi Ranjan Dey Department of Zoology, Rammohan College, 102/1, Raja Rammohan Sarani, Kolkata 09 2020 REPORT ON THE PROJECT Title of the project: Monitoring of Migratory Birds at selected water bodies of Murshidabad District: Introduction: The avian world has always been a fascination to the human world and has been a subject of our studies. Mythological documents hold a number of examples of birds being worshiped as goods with magical powers by the ancient civilizations. Even today winged wonders continue to be the subject of our astonishment primarily because of their ability to fly, their ability to build extraordinarily intricate nests, and of course, the brilliant colour of their plumage – features that no human being can replicate. Taxonomically birds are categorized in “Orders” “Families” and “Genera” and “species”. But overall they are divided into two groups: Passeriformes (or Passerines) and Non Passeriformes (non passerines). At least 60% of all bird species are Passeriformes or song birds, their distinguishing characteristics being their specialized leg structure, vocal structure and brain-wiring which allows them to produce complex songs. The non- passerine comprises 28 out of 29 orders of birds in the world. Throughout the world approximately 11,000 species are found. India is having 1301 species. West Bengal has 57.69% of the total avian fauna (750 species). Though there are many nomenclatures used by different people, we followed “Standardized common and scientific names of birds of Indian subcontinent by Manakadan and Pittie (2001).” Identification of bird is generally based on combination of various characteristics. -

HURRICANE KENNETH (EP132017) 18–23 August 2017

NATIONAL HURRICANE CENTER TROPICAL CYCLONE REPORT HURRICANE KENNETH (EP132017) 18–23 August 2017 Robbie Berg National Hurricane Center 26 January 2018 NASA-NOAA SUOMI NPP ENHANCED INFRARED SATELLITE IMAGE OF HURRICANE KENNETH AT 1034 UTC 21 AUGUST 2017 WHILE AT PEAK INTENSITY Kenneth was a category 4 hurricane (on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale) over the eastern North Pacific Ocean that did not affect land. Hurricane Kenneth 2 Hurricane Kenneth 18–23 AUGUST 2017 SYNOPTIC HISTORY Kenneth formed from the interaction of two tropical waves which moved off the west coast of Africa on 29 July and 2 August. The first wave moved across the Atlantic Ocean and northern South America at low latitudes and reached the eastern North Pacific Ocean on 8 August. At that point, the wave became more convectively active, but it moved only slowly westward for the next week due to its position south of Hurricane Franklin over the Bay of Campeche. In the meantime, the second tropical wave spawned Hurricane Gert over the western Atlantic, with the southern portion of the wave reaching the eastern North Pacific waters on 12 August. With the subtropical ridge rebuilding over the Gulf of Mexico, the second wave moved at a faster speed toward the west and reached the first tropical wave on 16 August (Fig. 1). The interaction of the two waves caused the development of a low by 1200 UTC 17 August about 530 n mi southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. Convective banding became more organized and persistent through the day, and the low was designated as a tropical depression by 0600 UTC 18 August about 585 n mi south- southwest of the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula. -

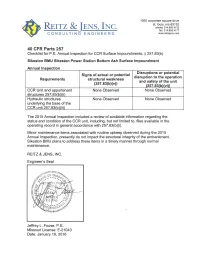

Inspection Report Checklist

SIKESTON POWER STATI ON Date October 6, 2015 Bottom Ash Pond Inspector Jeffrey Fouse, P.E. Annual Inspection Check Sheet Pool Level Estimated el. 315.9 Temperature 60ºs Weather Partly cloudy, dry Date of Previous Annual Inspection: Not Applicable (First Annual Inspection under §257.83(b).) Date of Previous Periodic Inspection: Not Applicable. Description of Emergency (EC) or Immediate Maintenance (IM) conditions observed since the last annual inspection: None Describe any action taken to restore or improve safety and integrity of impounding structure: None Describe any modifications to the geometry of the impounding structure since the previous annual inspection: None Describe any modifications to the operation of the impounding structure since the previous annual inspection: None (Scrubber sludge has not been placed in the Pond since 1998. The Water Recirculation Structure (NE corner) is no longer operational.) The emergency outfall is not operational. Impounded fly ash is blocking the outlet of the emergency outfall. List the approximate remaining storage capacity (Cubic Yards) of the impounding structure: Estimated available storage is 342,000 CY below el. 320 (allowing 2 feet of freeboard) List the approximate maximum, minimum and present depth and elevation of the impounded water since the previous annual inspection: Estimated from inspection reports since Oct. 2015: Max. Elev. 319.0 (Depth 17.0’); Min. Elev. 315.9 (Depth 13.9’); Avg. Elev. 318.5 (Depth 16.5’) List the approximate maximum, minimum and present depth and elevation of the impounded CCR since the previous annual inspection: CCR occupies approximately 41 acres at an approx. Max. Elev. 325.0 (Depth 23.0’). -

(CCR) Pond Capping

GEOSYNTHETICS High-Performance Geosynthetics PLAN VIEW for Ash (CCR) Pond Capping TenCate, the world’s leading provider of geosynthetics and industrial fabrics, offers TENCATE PANEL SEAMS new, quick and safe ways to treat waste FILL materials produced by industrial facilities. High-performance geosynthetics are used to stabilize soft/wet ash ponds, allowing the placement of the top cover system Fill soil is placed over the sludge/ash pond. and compacted fill. TENCATE HIGH-PERFORMANCE GEOTEXTILE PANEL Pond capping with TenCate’s geotextiles has become a viable alternative due to HIGH TENSION IN PORE WATER PRESSURE SLUDGE SLUDGE many advantages: SEAMS DEVELOPS POND LIMIT • Engineered seams allow for efficient installation of large geotextile panels with When fill is placed over the geotextile panel, the sludge/ash will increase in extremely high seam strengths to create shear strength as pore water pressures dissipate through the panels. a stable capping system. • Quickly and safely facilitates the complete closure of storage basins and ponds. • Allows water to pass through to relieve pore pressure. • Contains the fine-grained sludge material below, and separates sludge from clean fill above. Without high-performance geotextiles, High seam strengths are critical to the field performance of the panels to pond capping would be extremely difficult prevent rupture during fill placement over the low-bearing capacity sludge/ash. or impossible to perform. With expert Geotextile advantages engineering knowledge, the right tools and include excellent separation, experience, TenCate has successfully higher tensile strength and large seaming panels for designed numerous pond capping and quicker installation. closure projects all over the world. -

Plant Branch Electricity While Minimizing the Company’S Environmental Impact

Environment – A Balanced Approach At Georgia Power, we strive to provide our customers with reliable and affordable Plant Branch electricity while minimizing the company’s environmental impact. To meet the needs of 2.5 million customers, Georgia Power has created a diverse energy portfolio Ash pond closure and dewatering that delivers sustainable power. Georgia Power is permanently closing its 29 ash ponds at At Georgia Power, compliance with federal and state environmental requirements 11 coal-fired power plants across the state and has committed is only the beginning of our environmental commitment. In addition to compliance, we emphasize conservation and recycling, and help our customers make efficient that all ash ponds will stop receiving coal ash within three years. use of energy. We challenge ourselves every day to preserve the environment and strengthen the communities in which we live, work and serve. Additionally, the company is completely removing the ash from 19 ponds located adjacent to lakes or rivers where advanced Cornerstones of Our Commitment engineering methods designed to enhance the protection of Three principles serve as the cornerstones of our environmental commitment: groundwater around the closed pond may not be feasible. The Solutions ash from these ponds will either be relocated to a permitted Our environmental record is a top priority and we are taking steps in the communities we serve to improve the environment, including investing more than $5 billion landfill, consolidated with other closing ash ponds or recycled for in environmental controls at our power plants in Georgia. beneficial use. More than 60 percent of the coal ash Georgia Power Balance We strive to maintain a balance that furthers environmental stewardship while produces today is recycled for various uses such as Portland providing for growing energy needs and the economy. -

Annual Groundwater Monitoring and Corrective Action Report Ash Pond Ab

www.haleyaldrich.com REPORT ON ANNUAL GROUNDWATER MONITORING AND CORRECTIVE ACTION REPORT ASH POND A.B. BROWN GENERATING STATION POSEY COUNTY, INDIANA by Haley & Aldrich, Inc. Greenville, South Carolina for Southern Indiana Gas and Electric Company Evansville, Indiana File No. 129420 January 2019 Table of Contents Page List of Tables i List of Figures i 1. 40 CFR § 257.90 Applicability 1 1.1 40 CFR § 257.90(a) 1 1.2 40 CFR § 257.90(e) - SUMMARY 1 1.2.1 Status of the Groundwater Monitoring Program 1 1.2.2 Key Actions Completed 1 1.2.3 Problems Encountered 2 1.2.4 Actions to Resolve Problems 2 1.2.5 Project Key Activities for Upcoming Year 2 1.3 40 CFR § 257.90(e) - INFORMATION 2 1.3.1 40 CFR § 257.90(e)(1) 2 1.3.2 40 CFR § 257.90(e)(2) 3 1.3.3 40 CFR § 257.90(e)(3) 3 1.3.4 40 CFR § 257.90(e)(4) 3 1.3.5 40 CFR § 257.90(e)(5) 3 Tables Figures Appendix A – Alternate Source Demonstration List of Tables Table No. Title I Groundwater Monitoring Well Location and Construction Details II Summary of Groundwater Quality Data List of Figures Figure No. Title 1 Ash Pond Monitoring Well Location Map i 1. 40 CFR § 257.90 Applicability 1.1 40 CFR § 257.90(a) Except as provided for in § 257.100 for inactive CCR surface impoundments, all CCR landfills, CCR surface impoundments, and lateral expansions of CCR units are subject to the groundwater monitoring and corrective action requirements under § 257.90 through § 257.98. -

Chetumal Bay, Mexico ______

_____________________________________________________________________________ Cross Sectoral Initiatives in Democracy and Environment: Chetumal Bay, Mexico _____________________________________________________________________________ Rubinoff, P., R. Romero, and O. Chavez 2001 Citation: Narragansett, Rhode Island USA, Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island InterCoast Newsletter 40 For more information contact: Pamela Rubinoff, Coastal Resources Center, Graduate School of Oceanography, University of Rhode Island. 220 South Ferry Road, Narragansett, RI 02882 Telephone: 401.874.6224 Fax: 401.789.4670 Email: [email protected] This five year project aims to conserve critical coastal resources in Mexico by building capacity of NGOs, Universities, communities and other key public and private stakeholders to promote an integrated approach to participatory coastal management and enhanced decision-making. This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Office of Environment and Natural Resources Bureau for Economic Growth, Agriculture and Trade under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. PCE-A-00-95-0030-05. Cross Sectoral Initiatives in Democracy and Environment:Chetumal Bay, Mexico By Pamela Rubinoff, Rafael Romero, and Octavio grated management initiative in Chetumal Bay.” One of the key Chavez goals was to have a well-attended meeting (later called the he environment/democracy linkage has recently been initiat- Chetumal Bay Summit) of key stakeholders to discuss the -

Review of Available Technologies for the Removal of Selenium from Water

Final Report Review of Available Technologies for the Removal of Selenium from Water Prepared for North American Metals Council June 2010 Tom Sandy, P.E. CH2M HILL 11301 Carmel Commons Blvd. Suite 304 Charlotte, NC 28226 Cindy DiSante, P.E. CH2M HILL 1100 112th Avenue NE, Suite 400 Bellevue, WA 98004 I Acknowledgements The North American Metals Council – Selenium Work Group and CH2M HILL would like to thank its members who contributed their experiences in management of selenium documented within this report. The Council and CH2M HILL also thanks the following sector leads for their time and contribution to this report: Alan Prouty (mining and agriculture), Keith Finley (power generation), and Sarah Armstrong (oil and gas). CH2M HILL also thanks Ron Jones, William Adams, and Peter Chapman for their guidance and contribution to this report. The following CH2M HILL technologists contributed to this review: Harry Ohlendorf, Kar Munirathinam, Thomas Higgins, Jim Jordahl, Jim Bays, Dennis Fink, and Jamal Shamas. COPYRIGHT 2010 BY CH2M HILL, INC. III Executive Summary This document describes industry-specific approaches to prevention, control and removal of selenium in water, with a focus on water treatment approaches for selenium removal. Industries represented in the North American Metals Council - Selenium Work Group (NAMC-SWG) are faced with managing selenium in water from processes that include the mining, agriculture, power generation, and oil and gas industry sectors. Case studies of pilot-scale and full-scale treatment technologies for selenium removal are presented for each industry sector. The development of low cost, reliable technologies to remove selenium from water is a priority for the industry sectors as environmental standards and criteria applicable to their surface water discharges are currently very low with a potential for them to be even lower given pending guidance by regulatory agencies in North America. -

Changes in the Fish Community of a Western Caribbean Estuary After the Expansion of an Artificial Channel to the Sea

water Article Changes in the Fish Community of a Western Caribbean Estuary after the Expansion of an Artificial Channel to the Sea Juan J. Schmitter-Soto * and Roberto L. Herrera-Pavón El Colegio de la Frontera Sur, Av. Centenario km 5.5, Chetumal 77014, Quintana Roo, Mexico; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +52-983-835-0440 (ext. 4302) Received: 30 October 2019; Accepted: 2 December 2019; Published: 6 December 2019 Abstract: Increased connectivity between coastal lagoons and the sea is expected to entail a greater proportion of marine species in the former. Chetumal Bay, estuary of the Hondo river into the Caribbean, had a limited access to the sea until the opening of the Zaragoza Canal. We sought changes in the fish community from 1999–2001 (just after an expansion of the canal) to 2015–2018. The same fishing gear was used, in the same localities, during all seasons. Total fish abundance and mean local richness decreased, although total abundance increased in the polyhaline zone. Diversity was greater in the oligohaline zone in 1999–2001, and in the mesohaline zone in 2015–2018. Three guilds were absent in 2015–2018: Medium-sized herbivores, large piscivores, and medium-sized planktivores. Abundance of small benthivores decreased by decade; medium-sized piscivores and small planktivores became more abundant in 2015–2018 in the polyhaline zone. These changes may be due to the opening of the channel, but illegal fishing outside the bay may explain the decrease in juveniles of large piscivores, and erosion in the innermost part may be destroying important habitats. -

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 256 CAYS of the BELIZE

ATOLL RESEARCH BULLETIN No. 256 CAYS OF THE BELIZE BARRIER REEF AND LAGOON by D . R. Stoddart, F. R. Fosberg and D. L. Spellman Issued by THE SMlTHSONlAN INSTITUTION Washington, D. C., U.S.A. April 1982 CONTENTS List of Figures List of Plates i i Abstract 1 1. Introduction 2 2. Structure and environment 5 3. Sand cays of the northern barrier reef 9 St George's East Cay Paunch Cay Sergeant' s Cay Curlew Cay Go£ f ' s Cay Seal Cay English Cay Sandbore south of English Cay Samphire Spot Rendezvous Cay Jack's Cays Skiff Sand Cay Glory Tobacco Cay South Water Cay Carrie Bow Cay Curlew Cay 5. Sand cays of the southern barrier reef 23 Silk or Queen Cays North Silk Cay Middle Silk Cay Sauth Silk Cay Samphire Cay Round Cay Pompion Cay Ranguana Cay North Spot Tom Owen's Cay Tom Owen's East Cay Tom Owen's West Cay Cays between Tom Owen's Cays and Northeast Sapodilla Cay The Sapodilla Cays Northeast Sapodilla Cay Frank 's Cays Nicolas Cay Hunting Cay Lime Cay Ragged Cay Seal Cays 5. Cays of the barrier reef lagoon A. The northern lagoon Ambergris Cay Cay Caulker Cay Chapel St George ' s Cay Cays between Cay Chapel and Belize ~ohocay Stake Bank Spanish Lookout Cay Water Cay B. The Southern Triangles Robinson Point Cay Robinson Island Spanish Cay C. Cays of the central lagoon Tobacco Range Coco Plum Cay Man-o '-War Cay Water Range Weewee Cay Cat Cay Lagoon cays between Stewart Cay and Baker's Rendezvous Jack's Cay Buttonwood Cay Trapp 's Cay Cary Cay Bugle Cay Owen Cay Scipio Cay Colson Cay Hatchet Cay Little Water Cay Laughing Bird Cay Placentia Cay Harvest Cay iii D. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO Diploma Thesis

MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský MASARYK UNIVERSITY BRNO FACULTY OF EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LITERATURE Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Declaration I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. I agree with the placing of this thesis in the library of the Faculty of Education at the Masaryk University and with the access for academic purposes. Brno, 30th March 2018 …………………………………………. Bc. Lukáš Opavský Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor, doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. for his kind help and constant guidance throughout my work. Bc. Lukáš Opavský OPAVSKÝ, Lukáš. Presentation Sentences in Wikipedia: FSP Analysis; Diploma Thesis. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, English Language and Literature Department, 2018. XX p. Supervisor: doc. Mgr. Martin Adam, Ph.D. Annotation The purpose of this thesis is an analysis of a corpus comprising of opening sentences of articles collected from the online encyclopaedia Wikipedia. Four different quality categories from Wikipedia were chosen, from the total amount of eight, to ensure gathering of a representative sample, for each category there are fifty sentences, the total amount of the sentences altogether is, therefore, two hundred. The sentences will be analysed according to the Firabsian theory of functional sentence perspective in order to discriminate differences both between the quality categories and also within the categories. -

Preparedness and Mitigation in the Americas

PREPAREDNESS AND MITIGATION IN THE AMERICAS Issue No. 79 News and Information for the International Disaster Community January 2000 Inappropriate Relief Donations: What is the Problem? f recent disasters worldwide are any indication, Unsolicited clothing, canned foods and, to a lesser the donation of inappropriate supplies remains extent, pharmaceuticals and medical supplies, I a serious problem for the affected countries. continue to clog the overburdened distribution networks during the immediate aftermath of highly-publicized tragedies. This issue per- sists in spite of health guidelines issued by the World Health Organization, a regional policy adopted by the Ministries of Health of Latin America and the Caribbean, and the educational lobbying efforts of a consortium of primarily European NGOs w w w. wemos.nl). I N S I D E Now the Harvard School of Public Health has partially addressed the issue in a com- prehensive study of U.S. pharmaceutical News from d o n a t i o n s (w w w. h s p h . h a r v a r d . e d u / f a c u l t y / PAHO/WHO r e i c h / d o n a t i o n s / i n d e x . h t m). Although the 2 study correctly concluded that the "problem A sports complex in Valencia, Venezuela, which served as the main temporary shel- Other ter for the population displaced by the disaster, illustrates what happens when an may be more serious in disaster relief situa- Organizations enormous amount of humanitarian aid arrives suddenly in a country.