An Overview of the Status Quo and Development of Chinglish

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinglish: an Emerging New Variety of English Language?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Vol 4. No. 1 Mar 2009 Journal of Cambridge Studies 28 provided by Apollo Chinglish: an Emerging New Variety of English Language? ∗ You WANG PhD Candidate, Centre for Language and Language Education, Central China Normal University School of Foreign Languages and Research Centre for Languages and Literature, Jianghan University ABSTRACT: English, as a global language, is learned and used in China to fulfil the needs of international communication. In the non-Anglo-American sociocultural context, English language is in constant contact with the local language, Chinese. The contact gives birth to Chinglish, which is based on and shares its core grammar and vocabulary with British English. This paper investigates and tries to offer answers to the following two questions: 1. To what extent can Chinglish be tolerated in China? 2. Could Chinglish be a new variety of English language? KEY WORDS: Chinglish, Standard varieties of English, Non-native varieties of English INTRODUCTION For a long time, studies and learning of English in China have been focused on native-speaker Englishes, especially British English, and little attention has been paid to non-native varieties of English. At the times when non-native varieties were mentioned, it was often for the purpose of pointing out their deviances from Standard English. However, the status of English language in the world today is no longer what it used to be like. It is a property of the world, not only belonging to native-speakers, but to all speakers of English worldwide. -

Researcher 2015;7(8)

Researcher 2015;7(8) http://www.sciencepub.net/researcher “JANGLISH” IS CHEMMOZHI?...(“RAMANUJAM LANGUAGE”) M. Arulmani, B.E.; V.R. Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M. Phil. M.Arulmani, B.E. V.R.Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M.Phil. (Engineer) (Biologist) [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: Presently there are thousands of languages exist across the world. “ENGLISH” is considered as dominant language of International business and global communication through influence of global media. If so who is the “linguistics Ancestor” of “ENGLISH?”...This scientific research focus that “ANGLISH” (universal language) shall be considered as the Divine and universal language originated from single origin. ANGLISH shall also be considered as Ethical language of “Devas populations” (Angel race) who lived in MARS PLANET (also called by author as EZHEM) in the early universe say 5,00,000 years ago. Janglish shall be considered as the SOUL (mother nature) of ANGLISH. [M. Arulmani, B.E.; V.R. Hema Latha, M.A., M.Sc., M. Phil. “JANGLISH” IS CHEMMOZHI?...(“RAMANUJAM LANGUAGE”). Researcher 2015;7(8):32-37]. (ISSN: 1553-9865). http://www.sciencepub.net/researcher. 7 Keywords: ENGLISH; dominant language; international business; global communication; global media; linguistics Ancestor; ANGLISH” (universal language) Presently there are thousands of languages exist and universal language originated from single origin. across the world. “ENGLISH” is considered as ANGLISH shall also be considered as Ethical dominant language of International business and global language of “Devas populations” (Angel race) who communication through influence of global media. If lived in MARS PLANET (also called by author as so who is the “linguistics Ancestor” of EZHEM) in the early universe say 5,00,000 years ago. -

Eurolanguages-2019: Innovations and Development

MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF UKRAINE DNIPRO UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY INSTITUTE OF POWER ENGINEERING TRANSLATION DEPARTMENT EUROLANGUAGES-2019: INNOVATIONS AND DEVELOPMENT 17th INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS’ CONFERENCE, DEVOTED TO THE EUROPEAN DAY OF LANGUAGES Collection of students’ scientific abstracts Digital Edition Dnipro 2019 МІНІСТЕРСТВО ОСВІТИ І НАУКИ УКРАЇНИ НТУ «ДНІПРОВСЬКА ПОЛІТЕХНІКА» ІНСТИТУТ ЕЛЕКТРОЕНЕРГЕТИКИ КАФЕДРА ПЕРЕКЛАДУ ЄВРОПЕЙСЬКІ МОВИ-2019: ІННОВАЦІЇ ТА РОЗВИТОК 17-a МІЖНАРОДНА СТУДЕНТСЬКА КОНФЕРЕНЦІЯ, ПРИСВЯЧЕНА ЄВРОПЕЙСЬКОМУ ДНЮ МОВ Збірник студентських наукових робіт Електронне видання Дніпро 2019 УДК 811.11 (043.2) ББК 81я43 Є22 Європейські мови – 2019: інновації та розвиток: за матеріалами 17-ї міжнародної студентської конференції. //Збірник наук.студ. робіт. – Електронне видання. – Дніпро, НТУ "Дніпровська політехніка", 2019. – 178 с. Збірник наукових студентських робіт призначено для широкого кола читачів, які цікавляться проблемами вивчення іноземних мов та перекладу в Україні та за кордоном. The collection of students’ abstracts is designed for a large circle of readers who are interested in the state of learning foreign languages and translation both in Ukraine and abroad. Редакційна колегія: Відповідальний редактор: канд. філол. наук, проф. Т.Ю. Введенська, Україна Члени редколегії: докт. філол. наук, проф. А.Я. Алєксєєв, Україна канд. філол. наук, доц. Л.В. Бердник, Україна магістр, ст. викладач О.В. Щуров, Україна Відповідальна за випуск: канд. філол. наук, проф. Т.Ю. Введенська, Україна УДК 811.11 (043.2) ©Державний вищий навчальний заклад ББК 81я43 «Національний гірничий університет»®, 2019 4 ЗМІСТ СЕКЦІЯ ПЕРША ФІЛОЛОГІЧНІ ДОСЛІДЖЕННЯ Ndiae Ibrahima. SENEGAL: CULTURAL AND GEOGRAPHIC PECULIARITIES…………………………………………………………………..10 Дрок Ю. ЛІНГВОСТИЛІСТИЧНІ ОСОБЛИВОСТІ ПОЕЗІЇ ЕДРІЕНН РІЧ “POWERS OF RECUPERATION”………………………………………………11 Кіяшко Д. ДЕЯКІ ОСОБЛИВОСТІ ПЕЙЗАЖНОГО ОПИСУ В РОМАНІ С. -

Pamapla 36 Acalpa 36

PAMAPLA 36 PAPERS FROM THE 36TH ANNUAL MEETING OF THE ATLANTIC PROVINCES LINGUISTIC ASSOCIATION Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia November 2-3, 2012 ACALPA 36 ACTES DU 36E COLLOQUE ANNUEL DE L’ASSOCIATION DE LINGUISTIQUE DES PROVINCES ATLANTIQUES Université Saint Mary’s, Halifax, Nouvelle-Écosse 2-3 novembre 2012 EDITED BY / RÉDACTION EGOR TSEDRYK © 2013 by individual authors of the papers © 2013 Auteures et auteurs des communications Papers from the 36th Annual Meeting of the Atlantic Provinces Linguistic Association, Volume 36 Actes du 36e Collogue annuel de l’association de linguistique des provinces atlantiques, v. 36 Legal deposit / Depôt legal: 2015 Library and Archives Canada Bibliothèque et Archives Canada ISSN: 2368-7215 TABLE OF CONTENTS / TABLE DES MATIÈRES EGOR TSEDRYK, Saint Mary’s University About APLA/ALPA 36..............................................................................................................1 PHILIP AGADAGBA, University of Regina La question de la motivation ambiguë dans la création de vocabulaires gastronomiques français .......................................................................................................................................3 PATRICIA BALCOM, Université de Moncton Les apprenants utilisent cet ordre souvent: Early stages in the acquisition of adverb placement and negation in L2 French ......................................................................................11 ELIZABETH COWPER, University of Toronto The rise of featural modality in English ..................................................................................23 -

Languages of New York State Is Designed As a Resource for All Education Professionals, but with Particular Consideration to Those Who Work with Bilingual1 Students

TTHE LLANGUAGES OF NNEW YYORK SSTATE:: A CUNY-NYSIEB GUIDE FOR EDUCATORS LUISANGELYN MOLINA, GRADE 9 ALEXANDER FFUNK This guide was developed by CUNY-NYSIEB, a collaborative project of the Research Institute for the Study of Language in Urban Society (RISLUS) and the Ph.D. Program in Urban Education at the Graduate Center, The City University of New York, and funded by the New York State Education Department. The guide was written under the direction of CUNY-NYSIEB's Project Director, Nelson Flores, and the Principal Investigators of the project: Ricardo Otheguy, Ofelia García and Kate Menken. For more information about CUNY-NYSIEB, visit www.cuny-nysieb.org. Published in 2012 by CUNY-NYSIEB, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, 365 Fifth Avenue, NY, NY 10016. [email protected]. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Alexander Funk has a Bachelor of Arts in music and English from Yale University, and is a doctoral student in linguistics at the CUNY Graduate Center, where his theoretical research focuses on the semantics and syntax of a phenomenon known as ‘non-intersective modification.’ He has taught for several years in the Department of English at Hunter College and the Department of Linguistics and Communications Disorders at Queens College, and has served on the research staff for the Long-Term English Language Learner Project headed by Kate Menken, as well as on the development team for CUNY’s nascent Institute for Language Education in Transcultural Context. Prior to his graduate studies, Mr. Funk worked for nearly a decade in education: as an ESL instructor and teacher trainer in New York City, and as a gym, math and English teacher in Barcelona. -

English Loanwords in Italian IT Terminology

English loanwords in Italian IT terminology Originally published as a comment to Denglisch, Franglais, Spanglish, Swenglist and the like, a guest post by Ivan Kanič in BIK Terminology. Licia Corbolante – Terminologia etc. The use of English words in Italian is variously described as itanglese, itangliano or anglitaliano. Unsurprisingly, assorted pundits regularly voice their concern about the “invasion” of English words, and bemoan the lack of an Italian language authority that might provide guidelines on neologisms and terminology standardization, yet, according to recent data, use of loanwords is not yet widespread in everyday speech (anglicisms amount to only about 0.7% of basic vocabulary) and it is mainly restricted to specialized domains, such as information technology, economics, finance, politics, sports and fashion. As an Italian terminologist working mainly in the IT field, when working with new concepts – and the Italian terminology that should be associated to it – I take into account different variables, such as end user (e.g. consumer or professional?), type of product and its penetration (influential market leader or newcomer, mainstream or niche?), origin of the term (IT-specific or transdisciplinary borrowing?), its usage (industry-wide or producer/product-specific?), users’ familiarity with the term (is it known only to early adopters and/or subject matter experts or also to standard users?). Additionally, there are some linguistic trends that help identify the type of words that are more likely to be borrowed from English. A few examples: . Semantic neologisms (cf BIK Terminology on terminologization) cannot always be reproduced easily in Italian; generally speaking, metaphors associated with living beings, their features or actions tend to be rejected by Italian speakers and loanwords are used instead (e.g. -

ALMEIDA JACQUELINE TORIBIO Professor of Linguistics the University of Texas at Austin Email: [email protected]

ALMEIDA JACQUELINE TORIBIO Professor of Linguistics The University of Texas at Austin Email: [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Linguistics, Cornell University, 1993 M.A., Linguistics & Cognitive Science, Brandeis University, 1987 B.A., French and Psychology, Cornell University, 1985 APPOINTMENTS Professor of Linguistics, Department of Spanish & Portuguese, The University of Texas at Austin, 2009-present Director, Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program, 2017-present Affiliated faculty: Lozano Long Institute for Latin American Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, 2009-present Affiliated faculty: Department of African and African Diaspora Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, 2011-present Affiliated faculty: Warfield Center for African and African-American Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, 2009-present Professor of Linguistics, Linguistic Society of America Summer Institute, 2011 Professor of Linguistics, The Department of Spanish, Italian, & Portuguese, The Pennsylvania State University, 1999-2009 Professor of Linguistics, Department of Spanish & Portuguese, The University of California at Santa Barbara, 1993-1999 Visiting Scholar, Department of Linguistics & Philosophy, Massachusetts Institute of Technology RESEARCH AREAS Disciplines: Linguistics Major fields: corpus linguistics; structural linguistics; sociolinguistics Interests: language contact; language and social identity I. RESEARCH AND SCHOLARLY PRODUCTS BOOKS AND WEB-BASED PRODUCTS 1. Bullock, Barbara E. & Toribio, Almeida Jacqueline. 2012. The Spanish in Texas Corpus Project. COERLL, The University of Texas at Austin. http://www.spanishintexas.org 2. Bullock, Barbara E. & Toribio, Almeida Jacqueline (eds.). 2009. The Cambridge Handbook of Linguistic Code-switching. Cambridge University Press. REFEREED JOURNAL PUBLICATIONS 1. Bullock, Barbara E.; Larsen Serigos, Jacqueline & Toribio, Almeida Jacqueline. Accepted. The use of loan translations and its consequences in an oral bilingual corpus. -

The Tolerance of English Instructors Towards the Thai-Accented English and Grammatical Errors

INDONESIAN JOURNAL OF APPLIED LINGUISTICS Vol. 9 No. 3, January 2020, pp. 685-694 Available online at: https://ejournal.upi.edu/index.php/IJAL/article/view/23219 doi: 10.17509/ijal.v9i3.23219 The tolerance of English instructors towards the Thai-accented English and grammatical errors Varisa Osatananda and Parichart Salarat* Department of English, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, Khlong Luang, Pathum Thani, Thailand Kasetsart University, 50 Thanon Ngamwongwan, Lat Yao, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900, Thailand ABSTRACT Although Thai English has emerged as one variety of World Englishes (Trakulkasemsuk 2012, Saraceni 2015), it has not been enthusiastically embraced by Thai educators, as evidenced in the frustration expressed by ELT practitioners over Thai learners’ difficulties with pronunciation (Noom-ura 2013; Sahatsathatsana, 2017) as well as grammar (Saengboon 2017a). In this study, we examine the perception English instructors have on the different degrees of grammar skills and Thai-oriented English accent. We investigated the acceptability and comprehensibility of both native-Thai and native-English instructors (ten of each), as these subjects listen to controlled passages produced by 4 Thai-English bilingual speakers and another 4 native-Thai speakers. There were 3 types of passage tokens: passages with correct grammar spoken in a near-native English accent, passages with several grammatical mistakes spoken in a near-native English accent, and the last being a Thai-influenced accent with correct grammar. We hypothesized that (1) native-Thai instructors would favor the near-native English accent over correct grammar, (2) native-English instructors would be more sensitive to grammar than a foreign accent, and (3) there is a correlation between acceptability and comprehensibility judgment. -

Anna Enarsson New Blends in the English Language Engelska C

Estetisk-filosofiska fakulteten Anna Enarsson New Blends in the English Language Engelska C-uppsats Termin: Höstterminen 2006 Handledare: Michael Wherrity Karlstads universitet 651 88 Karlstad Tfn 054-700 10 00 Fax 054-700 14 60 [email protected] www.kau.se Titel: New Blends in the English Language Författare: Anna Enarsson Antal sidor: 29 Abstract: The aim of this essay was to identify new blends that have entered the English language. Firstly six different word-formation processes, including blending, was described. Those were compounding, clipping, backformation, acronyming, derivation and blending. The investigation was done by using a list of blends from Wikipedia. The words were looked up in the Longman dictionary of 2005 and in a dictionary online. A google search and a corpus investigation were also conducted. The investigation suggested that most of the blends were made by clipping and the second most common form was clipping and overlapping. Blends with only overlapping was unusual and accounted for only three percent. The investigation also suggested that the most common way to create blends by clipping was to use the first part of the first word and the last part of the second word. The blends were not only investigated according to their structure but also according to the domains they occur in. This part of the investigation suggested that the blends were most frequent in the technical domain, but also in the domain of society. Table of contents 1. Introduction and aims..........................................................................................................1 -

Denglisch (=Deutsch+Englisch) : Wenn Sprachen Miteinander „Kollidieren“ Guido OEBEL

J. Fac. Edu. Saga Univ. Vol. 16, No. 1 (2011)Denglisch143〜148(= Deutsch + englisch) :Wenn Sprachen miteinander „kollidieren“ 143 Denglisch (=Deutsch+Englisch) : Wenn Sprachen miteinander „kollidieren“ Denglish (=German+English) : When Languages Collide Guido OEBEL Summary Denglisch - Denglish - Neudeutsch :Some people claim that the words aboveall mean the same thing, but they donʼt. even the term “Denglisch” alone hasseveral different meanings. Since the word “Denglis(c)h” is not found in German dictionaries (even recent ones), and “Neudeutsch” isvaguely defined as “die deutsche Sprache der neueren Zeit” (“the German language of more recent times”), it can be difficulttocome up with a gooddefinition. Key words : German - english - Anglicisms - Language Policy - Linguistics But here are five different definitions for Denglisch (or Denglish)1) : s Denglisch 1 : The useof english words in German,with an attempttoincorporate them into German grammar. Examples: downloaden - ich habe den File gedownloadet/downgeloadet. - Heute haben wir ein Meeting mit den Consultants.* s Denglisch 2 : The (excessive) useof english words, phrases, or slogans in German advertising. Example : A recent German magazine ad for the German airline Lufthansa prominently displays the slogan : “Thereʼs no better way to fly.” s Denglisch 3 : The (bad) influences of english spellingan dpunctuation on German spellingan d punctuation. One pervasiveexample : The incorrect useof an apostrophe in German possessive forms, as in Karlʼs Schnellimbiss. Thiscommon error can be seen even on signs andpainted on the sideof trucks.Itis even seen for plurals endingin s.Another exampleis agrowingten dency to drop the hyphen (English-style) in German compound words: Karl Marx Straße vs Karl-Marx-Straße. s Denglisch 4 : The mixingo f englishand German vocabulary (in sentences) by english-speaking expatswhose German skills are weak. -

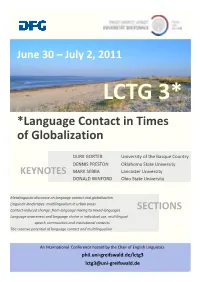

*Language Contact in Times of Globalization

June 30 –July 2, 2011 LCTG 3* *Language Contact in Times of Globalization DURK GORTER University of the Basque Country DENNIS PRESTON Oklahoma State University KEYNOTES MARK SEBBA Lancaster University DONALD WINFORD Ohio State University Metalinguistic discourse on language contact and globalization Linguistic landscapes: multilingualism in urban areas Contact‐induced change: from language mixing to mixed languages SECTIONS Language awareness and language choice in individual use, multilingual speech communities and institutional contexts The creative potential of language contact and multilingualism An International Conference hosted by the Chair of English Linguistics phil.uni‐greifswald.de/lctg3 lctg3@uni‐greifswald.de List of participants This list comprises the names, affiliations and email addresses of all participants which will actively contribute to our conference. Prof. Dr. Jannis University of Hamburg jannis.androutsopoulos@uni- Androutsopoulos hamburg.de Dr. Birte Arendt University of Greifswald [email protected] Dr. Mikko Bentlin University of Greifswald [email protected] Prof. Dr. Thomas G.Bever University of Arizona [email protected] Dr. Olga Bever University of Arizona [email protected] Prof. Dr. Hans Boas University of Texas [email protected] Petra Bucher University of Halle- [email protected] Wittenberg halle.de Melanie Burmeister University of Greifswald melanie.burmeister@uni- greifswald.de Lena Busse University of Potsdam [email protected] Viorica Condrat Alecu Russo State [email protected] University of Balti Dr. Jennifer Dailey- University of Alberta jennifer.dailey-o'[email protected] O’Cain Dr. Karin Ebeling University of Magdeburg [email protected] Dr. Martina Ebi University of Tuebingen [email protected] David Eugster University of Zurich [email protected] Konstantina Fotiou University of Essex [email protected] Matt Garley University of Illinois [email protected] Edward Gillian Gorzów Wielkopolski [email protected] Dr. -

Учебно-Методический Комплект Enjoy English / «Английский С

УДК 373.167.1:811.111 ББК 81.2Англ–92 Б59 Аудиоприложение доступно на сайте росучебник.рф/audio Учебно-методический комплект Enjoy English / «Английский с удовольствием» для 11 класса состоит из следующих компонентов: • учебника • книги для учителя • рабочей тетради • аудиоприложения Биболетова, М. З. Б59 Английский язык : базовый уровень : 11 класс : учебник для об- щеобразовательных организаций / М. З. Биболетова, Е. Е. Бабушис, Н. Д. Снежко. — 5-е изд., стереотип. — М. : Дрофа, 2020. — 214, [2] с. : ил. — (Российский учебник : Enjoy English /«Английский с удоволь- ствием»). ISBN 978-5-358-23134-4 Учебно-методический комплект Enjoy English / «Английский с удовольствием» (11 класс) является частью учебного курса Enjoy English / «Английский с удоволь- ствием» для 2—11 классов общеобразовательных организаций. Учебник состоит из четырех разделов, каждый из которых рассчитан на одну учебную четверть. Разделы завершаются проверочными заданиями (Progress Check), позволяющими оценить достигнутый школьниками уровень овладения языком. Учебник обеспечивает подготовку к итоговой аттестации по английскому языку, предусмотренной для выпускников средней школы. Учебник соответствует Федеральному государственному образовательному стандарту среднего общего образования. УДК 373.167.1:811.111 ББК 81.2Англ–92 © Биболетова М. З., Бабушис Е. Е., Снежко Н. Д., 2015 © ООО «ДРОФА», 2016 ISBN 978-5-358-23134-4 © ООО «ДРОФА», 2019, с изменениями CONTENTS UNIT 1 Section Grammar focus Function Vocabulary Young People 1 Varieties Irregular plural Expressing opinion