TROPICAL STORM BETA (AL222020) 17–22 September 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast

Improving Tornado Warnings: from Observation to Forecast John T. Snow Regents’ Professor of Meteorology Dean Emeritus, College of Atmospheric and Geographic Sciences, The University of Oklahoma Major contributions from: Dr. Russel Schneider –NOAA Storm Prediction Center Dr. David Stensrud – NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Dr. Ming Xue –Center for Analysis and Prediction of Storms, University of Oklahoma Dr. Lou Wicker –NOAA National Severe Storms Laboratory Hazards Caucus Alliance Briefing Tornadoes: Understanding how they develop and providing early warning 10:30 am – 11:30 am, Wednesday, 21 July 2010 Senate Capitol Visitors Center 212 Each Year: ~1,500 tornadoes touch down in the United States, causing over 80 deaths, 100s of injuries, and an estimated $1.1 billion in damages Statistics from NOAA Storm Prediction Center Supercell –A long‐lived rotating thunderstorm the primary type of thunderstorm producing strong and violent tornadoes Present Warning System: Warn on Detection • A Warning is the culmination of information developed and distributed over the preceding days sequence of day‐by‐day forecasts identifies an area of high threat •On the day, storm spotters deployed; radars monitor formation, growth of thunderstorms • Appearance of distinct cloud or radar echo features tornado has formed or is about to do so Warning is generated, distributed Present Warning System: Warn on Detection Radar at 2100 CST Radar at 2130 CST with Warning Thunderstorms are monitored using radar A warning is issued based on the detected and -

14B.6 ESTIMATED CONVECTIVE WINDS: RELIABILITY and EFFECTS on SEVERE-STORM CLIMATOLOGY

14B.6 ESTIMATED CONVECTIVE WINDS: RELIABILITY and EFFECTS on SEVERE-STORM CLIMATOLOGY Roger Edwards1 NWS Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK Gregory W. Carbin NWS Weather Prediction Center, College Park, MD 1. BACKGROUND In 2006, NCDC (now NCEI) Storm Data, from By definition, convectively produced surface winds which the SPC database is directly derived, began to ≥50 kt (58 mph, 26m s–1) in the U.S. are classified as record whether gust reports were measured by an severe, whether measured or estimated. Other wind instrument or estimated. Formats before and after reports that can verify warnings and appear in the this change are exemplified in Fig. 1. Storm Data Storm Prediction Center (SPC) severe-weather contains default entries of “Thunderstorm Wind” database (Schaefer and Edwards 1999) include followed by values in parentheses with an acronym assorted forms of convective wind damage to specifying whether a gust was measured (MG) or structures and trees. Though the “wind” portion of the estimated (EG), along with the measured and SPC dataset includes both damage reports and estimated “sustained” convective wind categories (MS specific gust values, this study only encompasses the and ES respectively). MGs from standard ASOS and latter (whether or not damage was documented to AWOS observation sites are available independently accompany any given gust). For clarity, “convective prior to 2006 and have been analyzed in previous gusts” refer to all gusts in the database, regardless of studies [e.g., the Smith et al. (2013) climatology and whether thunder specifically was associated with any mapping]; however specific categorization of EGs and given report. -

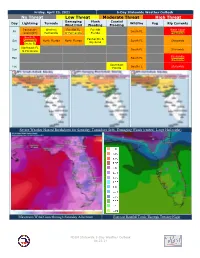

5-Day Weather Outlook 04.23.21

Friday, April 23, 2021 5-Day Statewide Weather Outlook No Threat Low Threat Moderate Threat High Threat Damaging Flash Coastal Day Lightning Tornado Wildfire Fog Rip Currents Wind/Hail Flooding Flooding Panhandle Western Far NW FL Far NW West Coast Fri South FL (overnight) Panhandle W Panhandle Florida Elsewhere North FL Panhandle & Sat Central FL North Florida North Florida South FL Statewide Big Bend South FL Northeast FL Sun South FL Statewide & Peninsula Panhandle Mon South FL Elsewhere Southeast Tue South FL Statewide Florida Severe Weather Hazard Breakdown for Saturday: Tornadoes (left), Damaging Winds (center), Large Hail (right) Maximum Wind Gusts through Saturday Afternoon Forecast Rainfall Totals Through Tuesday Night FDEM Statewide 5-Day Weather Outlook 04.23.21 …Potentially Significant Severe Weather Event for North Florida on Saturday…Two Rounds of Severe Weather Possible Across North Florida…Windy Outside of Storms in North Florida…Hot with Isolated Showers and Storms in the Peninsula this Weekend…Minor Coastal Flooding Possible in Southeast Florida Next Week… Friday - Saturday: A warm front over the Gulf of Mexico tonight will lift northward through the Panhandle and Big Bend Saturday morning. This brings the first round of thunderstorms into the Panhandle late tonight. The Storm Prediction Center has outlined the western Panhandle in a Marginal to Slight Risk of severe weather tonight (level 1-2 of 5). Damaging winds up to 60 mph and isolated tornadoes will be the main threat, mainly after 2 AM CT. On Saturday, the first complex of storms will be rolling across southern Alabama and southern Georgia in the morning and afternoon hours, clipping areas north of I-10 in Florida. -

NWS Storm Prediction Center SPC 24X7 Operations

3/6/2019 NWS Storm Prediction Center FACETs will enable ... • Robust quantification of the weather hazard risk Initial realizations of the FACETs Vision: Real- • Better individual and group decision making • Based on individual needs …through both NWS & the private sector time tools and information for severe weather • Consistent communication and DSS, commensurate to decision making risk • Rigorous quantification of potential impacts Dr. Russell S. Schneider Director, NOAA-NWS Storm Prediction Center 3 March 2019 National Tornado Summit – Public Sheltering Workshop NOAA NWS Storm Prediction Center www.spc.noaa.gov • Forecast tornadoes, thunderstorms, and wildfires nationwide • Forecast information from 8 days to a few minutes in advance • World class team engaged with the research community • Partner with over 120 local National Weather Service offices Current: Forecast & Warning Continuum SPC 24x7 Operations Information Void(s) Outlooks Watches Warnings Event Time Days Hours Minutes Space Regional State Local Uncertainty FACETs: Toward a true continuum optimal for the pace of emergency decision making 1 3/6/2019 Tornado Watch SPC Severe Weather Outlooks Alerting messages issued to the public through media partners SPC Forecaster collaborating on watch characteristics with local NWS offices to communicate the forecast tornado threat to the Public Issued since the early 1950’s SPC Lead Forecaster SPC Lead Forecaster National Experience Average National Experience: 10 years as Lead; almost 20 overall NWS Local Forecast Office Partners -

John Hart Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK

John Hart Storm Prediction Center, Norman, OK 7th European Conference on Severe Storms, Helsinki, Finland – Friday June 7th, 2013 SPC Overview: US Naonal Weather Service 122 Local Weather Forecast Offices Ususally about 12 meteoroloGists who work rotating shifts. Very busy with daily forecast tasks (public/aviation forecasts, etc). Limited severe weather experience, even if they work in an active office. Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group SPC Overview: US Storm Predic/on Center • Focus on severe storms. • Second set of eyes for the local offices. • Consistent overview of severe storm threat. • HIGH EXPERIENCE LEVELS Forecasts for entire US • Very competitive to join staff (except Alaska and Hawaii) • Stable staff • Few people leave before retirement • No competition with local offices • SPC does not issue warnings • Easy collaboration with local offices Our job is to help the local offices, not compete or overshadow. Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group SPC Overview: US Storm Predic/on Center • Usually four forecasters on shift • Lead Forecaster • 2 mesoscale forecasters • 1 outlook forecaster • Lead Forecaster • Shift supervisor • Makes final call on all products • Issues watches • Promoted from mesoscale/outlook forecaster ranks • Mesoscale Forecaster • Focuses on 0-6 hour forecasts • Writes mesoscale discussions • Outlook Forecaster • Focuses on longer ranges and larger scales • Days 1-8 • Write convective outlooks Image source: Steve M., Minnesota ClimatoloGy Working Group My Background -

The Birth and Early Years of the Storm Prediction Center

AUGUST 1999 CORFIDI 507 The Birth and Early Years of the Storm Prediction Center STEPHEN F. C ORFIDI NOAA/NWS/NCEP/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma (Manuscript received 12 August 1998, in ®nal form 15 January 1999) ABSTRACT An overview of the birth and development of the National Weather Service's Storm Prediction Center, formerly known as the National Severe Storms Forecast Center, is presented. While the center's immediate history dates to the middle of the twentieth century, the nation's ®rst centralized severe weather forecast effort actually appeared much earlier with the pioneering work of Army Signal Corps of®cer J. P. Finley in the 1870s. Little progress was made in the understanding or forecasting of severe convective weather after Finley until the nascent aviation industry fostered an interest in meteorology in the 1920s. Despite the increased attention, forecasts for tornadoes remained a rarity until Air Force forecasters E. J. Fawbush and R. C. Miller gained notoriety by correctly forecasting the second tornado to strike Tinker Air Force Base in one week on 25 March 1948. The success of this and later Fawbush and Miller efforts led the Weather Bureau (predecessor to the National Weather Service) to establish its own severe weather unit on a temporary basis in the Weather Bureau± Army±Navy (WBAN) Analysis Center Washington, D.C., in March 1952. The WBAN severe weather unit became a permanent, ®ve-man operation under the direction of K. M. Barnett on 21 May 1952. The group was responsible for the issuance of ``bulletins'' (watches) for tornadoes, high winds, and/or damaging hail; outlooks for severe convective weather were inaugurated in January 1953. -

U.S. Violent Tornadoes Relative to the Position of the 850-Mb

U.S. VIOLENT TORNADOES RELATIVE TO THE POSITION OF THE 850 MB JET Chris Broyles1, Corey K. Potvin 2, Casey Crosbie3, Robert M. Rabin4, Patrick Skinner5 1 NOAA/NWS/NCEP/Storm Prediction Center, Norman, Oklahoma 2 Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, and School of Meteorology, University of Oklahoma, and NOAA/OAR National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma 3 NOAA/NWS/CWSU, Indianapolis, Indiana 4 National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma 5 Cooperative Institute for Mesoscale Meteorological Studies, and NOAA/OAR National Severe Storms Laboratory, Norman, Oklahoma Abstract The Violent Tornado Webpage from the Storm Prediction Center has been used to obtain data for 182 events (404 violent tornadoes) in which an F4-F5 or EF4-EF5 tornado occurred in the United States from 1950 to 2014. The position of each violent tornado was recorded on a gridded plot compared to the 850 mb jet center within 90 minutes of the violent tornado. The position of each 850 mb jet was determined using the North American Regional Reanalysis (NARR) from 1979 to 2014 and NCEP/NCAR Reanalysis from 1950 to 1978. Plots are shown of the position of each violent tornado relative to the center of the 850 mb low-level jet. The United States was divided into four parts and the plots are available for the southern Plains, northern Plains, northeastern U.S. and southeastern U.S with a division between east and west at the Mississippi River. Great Plains violent tornadoes clustered around a center about 130 statute miles to the left and slightly ahead of the low-level jet center while eastern U.S. -

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms

Glossary of Severe Weather Terms -A- Anvil The flat, spreading top of a cloud, often shaped like an anvil. Thunderstorm anvils may spread hundreds of miles downwind from the thunderstorm itself, and sometimes may spread upwind. Anvil Dome A large overshooting top or penetrating top. -B- Back-building Thunderstorm A thunderstorm in which new development takes place on the upwind side (usually the west or southwest side), such that the storm seems to remain stationary or propagate in a backward direction. Back-sheared Anvil [Slang], a thunderstorm anvil which spreads upwind, against the flow aloft. A back-sheared anvil often implies a very strong updraft and a high severe weather potential. Beaver ('s) Tail [Slang], a particular type of inflow band with a relatively broad, flat appearance suggestive of a beaver's tail. It is attached to a supercell's general updraft and is oriented roughly parallel to the pseudo-warm front, i.e., usually east to west or southeast to northwest. As with any inflow band, cloud elements move toward the updraft, i.e., toward the west or northwest. Its size and shape change as the strength of the inflow changes. Spotters should note the distinction between a beaver tail and a tail cloud. A "true" tail cloud typically is attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same level as the wall cloud itself. A beaver tail, on the other hand, is not attached to the wall cloud and has a cloud base at about the same height as the updraft base (which by definition is higher than the wall cloud). -

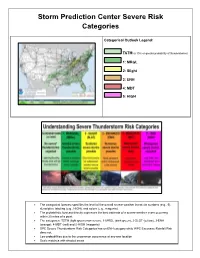

Storm Prediction Center Severe Risk Categories

Storm Prediction Center Severe Risk Categories Categorical Outlook Legend: TSTM (a 10% or greater probability of thunderstorms) 1: MRGL 2: Slight 3: ENH 4: MDT 5: HIGH • The categorical forecast specifies the level of the overall severe weather threat via numbers (e.g., 5), descriptive labeling (e.g., HIGH), and colors (e.g., magenta). • The probabilistic forecast directly expresses the best estimate of a severe weather event occurring within 25 miles of a point. • The categories: TSTM (light green) non-severe, 1-MRGL (dark green), 2-SLGT (yellow), 3-ENH (orange), 4-MDT (red) and 5-HIGH (magenta) • SPC Severe Thunderstorm Risk Categories has an ENH category while WPC Excessive Rainfall Risk does not. • Low probabilities due to the uncommon occurrence at any one location. • Scale matches with shaded areas Weather Prediction Center Excessive Rain Risk Categories Category Outlook legend: 1. 2. 3. 4. • The Weather Prediction Center (WPC) forecasts the probability that rainfall will exceed flash flood guidance (FFG) within 40 kilometers (25 miles) of a point. • Gridded FFG is provided by the twelve NWS River Forecast Centers (RFCs) whose service areas cover the lower 48 states. • WPC creates a national mosaic of FFG, whose 1, 3, and 6-hour values represent the amount of rainfall over those short durations which it is estimated would bring rivers and streams up to bankfull conditions. • WPC uses a variety of deterministic and ensemble-based numerical model tools that get at both the meteorological and hydrologic factors associated with flash flooding. • WPC ER Risk Categories are similar to SPC, however probability/percentages are very different. -

Investigating the Interpretation of the Storm Prediction Center’S Convective Outlook by Broadcast Meteorologists and the Us Public

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE COLORFUL LANGUAGE: INVESTIGATING THE INTERPRETATION OF THE STORM PREDICTION CENTER’S CONVECTIVE OUTLOOK BY BROADCAST METEOROLOGISTS AND THE US PUBLIC A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE IN METEOROLOGY By SEAN R. ERNST Norman, Oklahoma 2020 COLORFUL LANGUAGE: INVESTIGATING THE INTERPRETATION OF THE STORM PREDICTION CENTER’S CONVECTIVE OUTLOOK BY BROADCAST METEOROLOGISTS AND THE US PUBLIC A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF METEOROLOGY BY THE COMMITTEE CONSISTING OF Dr. Harold Brooks, Chair Dr. Elinor Martin Dr. Scott Salesky Dr. Naoko Sakaeda Dr. Joseph Ripberger Dr. Kodi Berry © Copyright by SEAN R. ERNST 2020 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my lead advisors, Dr. Joe Ripberger and Dr. Harold Brooks, for providing me guidance, opportunity, and funding to perform this research, without them I would not have been able to perform any of the research presented in this paper. I would also like to thank Dr. Kodi Berry and Holly Obermeier, who welcomed me into their CTA broadcaster study with open arms and helped me organize and record interviews with broadcasters from across the nation. As part of that effort, I would like to thank Joseph Trujillo and Emma Landeros for assisting with note-taking and moderation during the focus group and CTA interviews, both helped me keep track of all the information flying around so that I could focus on grilling the broadcasters! I’d be remiss without thanking Dr. Patrick Marsh for his assistance in outlining the development of the 5-tier SPC outlook and for encouraging my work on this project, having the ability to share my results and learn about future SPC product development was invaluable to this project. -

Mesoscale and Stormscale Ingredients of Tornadic Supercells Producing Long-Track Tornadoes in the 2011 Alabama Super Outbreak

MESOSCALE AND STORMSCALE INGREDIENTS OF TORNADIC SUPERCELLS PRODUCING LONG-TRACK TORNADOES IN THE 2011 ALABAMA SUPER OUTBREAK BY SAMANTHA L. CHIU THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Atmospheric Science in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Advisers: Professor Emeritus Robert B. Wilhelmson Dr. Brian F. Jewett ABSTRACT This study focuses on the environmental and stormscale dynamics of supercells that produce long-track tornadoes, with modeling emphasis on the central Alabama storms from April 27, 2011 - part of the 2011 Super Outbreak. While most of the 204 tornadoes produced on this day were weaker and short-lived, this outbreak produced 5 tornadoes in Alabama alone whose path-length exceeded 50 documented miles. The results of numerical simulations have been inspected for both environmental and stormscale contributions that make possible the formation and maintenance of such long–track tornadoes. A two-pronged approach has been undertaken, utilizing both ideal and case study simulations with the Weather Research and Forecasting [WRF] Model. Ideal simulations are designed to isolate the role of the local storm environment, such as instability and shear, to long-track tornadic storm structure. Properties of simulated soundings, for instance hodograph length and curvature, 0-1km storm relative helicity [SRH], 0-3km SRH and convective available potential energy [CAPE] properties are compared to idealized soundings described by Adlerman and Droegemeier (2005) in an effort to identify properties conducive to storms with non-cycling (sustained) mesocyclones. 200m horizontal grid spacing simulations have been initialized with the 18 UTC Birmingham/Alabaster, Alabama [KBMX] soundings, taken from an area directly hit by the day’s storms. -

The Storm Prediction Center's New Severe Thunderstorm Risk

NOAA’s National Weather Service December 2015 Inside CoCoRaHS Members The Storm Prediction Center’s New Severe Provide Vital Climate Information Thunderstorm Risk Categories Graphic 2 By Jim Reynolds, Meteorologist-in-Charge NWS Brownsville, TX NWS Now Provides Real-Time Mesoscale Pilots now have a new way to more accurately understand the severity of Analysis (RTMA): thunderstorms forecasted for an intended route of flight. Alternative Temperature In April, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC) released the graphic that you see Report in Figure 2 (see Page 2), which concisely describes the areal extent and weather 4 hazards associated with five increasing levels of severe thunderstorm risk. The new severe thunderstorm risk graphic is a big step forward in aviation Strong El Niño Expected safety. It was designed to help pilots make “go/no go” decisions when there is to Continue Through the potential for thunderstorm development. While few pilots should probably Winter 2015-16 attempt to fly through “3—Enhanced (ENH)” areas of severe thunderstorms 5 or greater, more skilled pilots might consider flying in areas labeled “1 – Marginal (MRGL)” or “2 – Slight (SLGT).” Figure 1, below, displays an SPC When’s the Next Front? Subscribe or unsubscribe Program Manager: Michael Graf Managing Editor: Melody Magnus Editor: Nancy Lee Mission Statement To enhance aviation safety by increasing the pilot’s knowledge of weather systems and processes and National Weather Service products and services. Figure 1 Figure 2 Convective Outlook/Severe Thunderstorm Risk graphic over portions of the north central Plains, east Texas, and showing how the different levels of risk look on a map Washington, D.C.