Lucy S. Dawidowicz and the Restitution of Jewish Cultural Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues

Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues Dr. Jonathan Petropoulos PROFESSOR, DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, LOYOLA COLLEGE, MD UNITED STATES Art Looting during the Third Reich: An Overview with Recommendations for Further Research Plenary Session on Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues It is an honor to be here to speak to you today. In many respects it is the highpoint of the over fifteen years I have spent working on this issue of artworks looted by the Nazis. This is a vast topic, too much for any one book, or even any one person to cover. Put simply, the Nazis plundered so many objects over such a large geographical area that it requires a collaborative effort to reconstruct this history. The project of determining what was plundered and what subsequently happened to these objects must be a team effort. And in fact, this is the way the work has proceeded. Many scholars have added pieces to the puzzle, and we are just now starting to assemble a complete picture. In my work I have focused on the Nazi plundering agencies1; Lynn Nicholas and Michael Kurtz have worked on the restitution process2; Hector Feliciano concentrated on specific collections in Western Europe which were 1 Jonathan Petropoulos, Art as Politics in the Third Reich (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press). Also, The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany (New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press, forthcoming, 1999). 2 Lynn Nicholas, The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1994); and Michael Kurtz, Nazi Contraband: American Policy on the Return of European Cultural Treasures (New York: Garland, 1985). -

Ursprung Und Entstehung Von NS-Verfolgungsbedingt

Ursprung und Entstehung von NS-verfolgungsbedingt entzogenem Kulturgut, die Anfänge der Restitution und ihre Bearbeitung aus heutiger Sicht am Beispiel der ULB Münster und der USB Köln Bachelorarbeit Studiengang Bibliothekswesen Fakultät für Informations- und Kommunikationswissenschaften Fachhochschule Köln vorgelegt von: Jan-Philipp Hentzschel Starenstr. 26 48607 Ochtrup Matr.Nr.: 11070940 am 01.02.2013 bei Prof. Dr. Haike Meinhardt Abstract (Deutsch) Die vorliegende Arbeit beschäftigt sich mit der Thematik der Restitution von NS- verfolgungsbedingt entzogenem Kulturgut. Während der Zeit des „Dritten Reichs“ pro- fitierten deutsche und österreichische Bibliotheken in hohem Maß von den Kulturgut- raubzügen der diversen NS-Organisationen. Millionen von Büchern gelangten aus dem In- und Ausland unrechtmäßig in ihre Bestände, wo sie lange unbeachtet verblieben. Erst in den 1980er Jahren begann man in Bibliothekskreisen mit einer kritischen Ausei- nandersetzung der NS-Vergangenheit, die in den 90er Jahren durch politische Erklärun- gen und erste Rechercheprojekte weiter forciert wurde. Seitdem wurden die Bemühun- gen, das NS-Raub- und Beutegut aufzuspüren, es an die rechtmäßigen Eigentümer oder Erben zurückzuerstatten und die Projekte umfassend zu dokumentieren, stetig intensi- viert. Dennoch gibt es viele Bibliotheken, die sich an der Suche noch nicht beteiligt ha- ben. Diese Arbeit zeigt die geschichtliche Entwicklung der Thematik von 1930 bis in die heutige Zeit auf und gewährt Einblicke in die Praxis. Angefangen bei der Vorstellung einflussreicher -

Division, Records of the Cultural Affairs Branch, 1946–1949 108 10.1.5.7

RECONSTRUCTING THE RECORD OF NAZI CULTURAL PLUNDER A GUIDE TO THE DISPERSED ARCHIVES OF THE EINSATZSTAB REICHSLEITER ROSENBERG (ERR) AND THE POSTWARD RETRIEVAL OF ERR LOOT Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Revised and Updated Edition Chapter 10: United States of America (March 2015) Published on-line with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), in association with the International Institute of Social History (IISH/IISG), Amsterdam, and the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust, and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, at http://www.errproject.org © Copyright 2015, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted The original volume was initially published as: Reconstructing the Record of Nazi Cultural Plunder: A Survey of the Dispersed Archives of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), IISH Research Paper 47, by the International Institute of Social History (IISH), in association with the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, and with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), Amsterdam, March 2011 © Patricia Kennedy Grimsted The entire original volume and individual sections are available in a PDF file for free download at: http://socialhistory.org/en/publications/reconstructing-record-nazi-cultural- plunder. Also now available is the updated Introduction: “Alfred Rosenberg and the ERR: The Records of Plunder and the Fate of Its Loot” (last revsied May 2015). Other updated country chapters and a new Israeli chapter will be posted as completed at: http://www.errproject.org. The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the special operational task force headed by Adolf Hitler’s leading ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, was the major NSDAP agency engaged in looting cultural valuables in Nazi-occupied countries during the Second World War. -

Handbook on Judaica Provenance Research: Ceremonial Objects

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron and members of the Synagogue Council of America depositing Torah scrolls in a grave at Beth El Cemetery, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 January 1952. Photograph by Fred Stein, collection of the American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBOOK ON JUDAICA PROVENANCE RESEARCH: CEREMONIAL OBJECTS By Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, and Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2018 Table of Contents Foreword, Wesley A. Fisher page 4 Disclaimer page 7 Preface page 8 PART 1 – Historical Overview 1.1 Pre-War Judaica and Jewish Museum Collections: An Overview page 12 1.2 Nazi Agencies Engaged in the Looting of Material Culture page 16 1.3 The Looting of Judaica: Museum Collections, Community Collections, page 28 and Private Collections - An Overview 1.4 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the West: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction page 43 1.5 The Dispersion of Jewish Ceremonial Objects in the East: The Soviet Trophy Brigades and Nationalizations in the East after World War II page 61 PART 2 – Judaica Objects 2.1 On the Definition of Judaica Objects page 77 2.2 Identification of Judaica Objects page 78 2.2.1 Inscriptions page 78 2.2.1.1 Names of Individuals page 78 2.2.1.2 Names of Communities and Towns page 79 2.2.1.3 Dates page 80 2.2.1.4 Crests page 80 2.2.2 Sizes page 81 2.2.3 Materials page 81 2.2.3.1 Textiles page 81 2.2.3.2 Metal page 82 2.2.3.3 Wood page 83 2.2.3.4 Paper page 83 2.2.3.5 Other page 83 2.2.4 Styles -

War Crimes Records Pp.77-83 National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records (RG 238)

1 First Supplement to the Appendix U.S. and Allied Efforts To Recover and Restore Gold and Other Assets Stolen or Hidden by Germany During World War II Finding Aid to Records at the National Archives at College Park Prepared by Dr. Greg Bradsher National Archives and Records Administration College Park, Maryland October 1997 2 Table of Contents pp.2-3 Table of Contents p.4 Preface Military Records pp.5-13 Records of the Office of Strategic Services (RG 226) pp.13-15 Records of the Office of the Secretary of War (RG 107) pp.15-22 Records of the War Department General and Special Staffs (RG 165) pp.22-74 Records of the United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II (RG 260) pp.22-72 Records of the Office of the Military Governor, United States OMGUS pp.72-74 Records of the U.S. Allied Commission for Austria (USACA) Section of Headquarters, U.S. Forces in Austria Captured Records pp.75-77 National Archives Collection of Foreign Seized Records (RG 242) War Crimes Records pp.77-83 National Archives Collection of World War II War Crimes Records (RG 238) Civilian Agency Records pp.84-88 General Records of the Department of State (RG 59) pp.84-86 Central File Records pp.86-88 Decentralized Office of “Lot Files” pp.88-179 Records of the Foreign Service Posts of the Department of State (RG 84) pp.88-89 Argentina pp.89-93 Austria pp.94-95 France pp.95-106 Germany pp.106-111 Great Britain pp.111-114 Hungary pp.114-117 Italy pp.117-124 Portugal pp.125-129 Spain pp.129-135 Sweden pp.135-178 Switzerland 3 pp.178-179 Turkey pp.179-223 Records of the American Commission for the Protectection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monumnts in War Areas (RG 239) pp.223-243 Records of the Foreign Economic Administration (RG 169) pp.243-244 Records of the High Commissioner for Germany (RG 466) pp.244-246 Records of the U.S. -

Handbuch Zur Judaica Provenienz Forschung: Zeremonialobjekte

Looted Art and Jewish Cultural Property Initiative Salo Baron und Mitglieder des Synagogue Council of America bei der Beerdigung von Torah Rollen beim Beth El Friedhof, Paramus, New Jersey, 13 Jänner 1952. Foto von Fred Stein, Sammlung der American Jewish Historical Society, New York, USA. HANDBUCH ZUR JUDAICA PROVENIENZ FORSCHUNG: ZEREMONIALOBJEKTE Von Julie-Marthe Cohen, Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek, und Ruth Jolanda Weinberger ins Deutsche übersetzt von: Felicitas Heimann-Jelinek Die deutsche Übersetzung kam dank der großzügigen Unterstützung der Beauftragten der Bundesregierung für Kultur und Medien zustande. ©Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, 2019 Inhalt Vorwort, Wesley A. Fisher Seite 4 Verzichtserklärung Seite 7 Einleitung Seite 8 TEIL 1 – Historische Übersicht 1.1. Judaica- und jüdische Museumssammlungen der Vorkriegszeit: Eine Übersicht Seite 12 1.2 Nazi-Organisationen und Raubkunst Seite 17 1.3 Die Plünderung von Judaica: Sammlungen von Museen, Gemeinden und Privatpersonen – Ein Überblick Seite 29 1.4 Die Zerstreuung jüdischer Zeremonialobjekte im Westen nach 1945: Jewish Cultural Reconstruction Seite 44 1.5 Die Zerstreuung jüdischer Zeremonialobjekte im Osten: Die Sowjetischen Trophäenbrigaden und Verstaatlichungen im Osten nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg Seite 63 TEIL 2 – Judaica Objekte 2.1 Zur Definition von Judaica-Objekten Seite 79 2.2 Zur Identifikation von Judaica-Objekten Seite 80 2.2.1 Inschriften Seite 80 2.2.1.1 Personennamen Seite 80 2.2.1.2 Gemeinde- und Ortsnamen Seite 81 2.2.1.3 Datierungen Seite -

Center for Jewish History Included in This

CLIR Annual Report: Center for Jewish History Included in this PDF: 1) Collections list 2) Processing guide 3) Collection-related blog posts: o http://16thstreet.tumblr.com/post/64961891338/out-of-the-archives-war-heroism-by- kevin o http://16thstreet.tumblr.com/post/63657058958/conservation-flattening-documents o http://16thstreet.tumblr.com/post/59788701057/out-of-the-archives-when-facebook- was-an-actual 4) Center for Jewish History work-report form: o https://docs.google.com/spreadsheet/viewform?usp=drive_web&formkey=dDFMS3lHY 0x0NnRCUmtnaDdEb0pWUUE6MQ#gid=0 Contact: Miriam Haier, Senior Manager for Communications and Publications, [email protected] Collections Processed on "Illuminating Collections at the Center for Jewish History" January 31, 2012-February 1, 2014 Partner Collection Title Linear Feet AJHS Chicago Action for Soviet Jewry Records 45 AJHS Leo Hershkowitz Collection of Court Records 32 AJHS Shirley T Joseph Papers 10.3 LBI Alexander Turney Collection 0.5 LBI Altschuler Family Collection 1 LBI Annemarie and Ellen Walter Collection 0.25 LBI Arthur Abelmann Collection 2.5 LBI Arthur and Vally Feigl Collection 0.25 LBI Arthur Lowy Family Collection 1 LBI Arthur Prinz Dickinson College Collection 3 LBI Bella and Ludwig Liebman Collection 0.25 LBI C. Theo Marx Family Collection 5 LBI Carol Kahn Strauss Family Collection 3 LBI Caroline Klein Collection 0.5 LBI Edward Littman Collection of Restitution Case Files 15 LBI Eleanor Alexander Collection 1 LBI Elizabeth S. Plaut Collection Addenda 1 LBI Else Herz Correspondence 1 LBI Emery I. Gondor Collection 4 LBI Emil Schorsch Collection Addenda 13 LBI Ernst and Ruth Lissner Collection 0.25 LBI Ettinger Family Collection 1 LBI Eva Schiffer Family Collection 1.5 LBI Florence Mendheim Collection of Anti-Semitic Propaganda 12.49 LBI Gerald Weiss Family Collection 1.25 LBI Gerda Dittmann Collection 2.75 LBI Gustav Beck Collection 7.5 LBI Hans David Blum Research Collection 6 LBI Harold W. -

M1947 Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point, 1945–1952

M1947 RECORDS CONCERNING THE CENTRAL COLLECTING POINTS (“ARDELIA HALL COLLECTION”): WIESBADEN CENTRAL COLLECTING POINT, 1945–1952 National Archives and Records Administration Washington, DC 2008 United States. National Archives and Records Administration. Records concerning the central collecting points (“Ardelia Hall Collection”) : Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point, 1945–1952.— Washington, D.C. : National Archives and Records Administration, 2008. p. ; cm.-- (National Archives microfilm publications. Publications describing ; M 1947) Cover title. 1. Hall, Ardelia – Archives – Microform catalogs. 2. Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945–1955 : U.S. Zone). Office of Military Government. Property Division – Archives – Microform catalogs. 3. Restitution and indemnification claims (1933– ) – Germany – Microform catalogs. 4. World War, 1939–1945 – Confiscations and contributions – Germany – Archival resources – Microform catalogs. 5. Cultural property – Germany (West) – Archival resources – Microform catalogs. I. Title. INTRODUCTION On 117 rolls of this microfilm publication, M1947, are reproduced the administrative records, photographs of artworks, and property cards from the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point during the period 1945–52. The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives (MFAA) Section recovered Nazi-looted works of art and artifacts from various storage areas and shipped the objects to one of four U.S. central collecting points, including Wiesbaden. In order to research restitution claims, MFAA officers gathered intelligence reports, interrogation reports, captured documents, and general information regarding German art looting. The Wiesbaden records are part of the “Ardelia Hall Collection” in Records of United States Occupation Headquarters, World War II, Record Group (RG) 260. BACKGROUND The basic authority for taking custody of property in Germany was contained in Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Directive 1067/6, which directed the U.S. -

Gershom Biography an Intellectual Scholem from Berlin to Jerusalem and Back Gershom Scholem

noam zadoff Gershom Biography An Intellectual Scholem From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back gershom scholem The Tauber Institute Series for the Study of European Jewry Jehuda Reinharz, General Editor ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Associate Editor Sylvia Fuks Fried, Associate Editor Eugene R. Sheppard, Associate Editor The Tauber Institute Series is dedicated to publishing compelling and innovative approaches to the study of modern European Jewish history, thought, culture, and society. The series features scholarly works related to the Enlightenment, modern Judaism and the struggle for emancipation, the rise of nationalism and the spread of antisemitism, the Holocaust and its aftermath, as well as the contemporary Jewish experience. The series is published under the auspices of the Tauber Institute for the Study of European Jewry —established by a gift to Brandeis University from Dr. Laszlo N. Tauber —and is supported, in part, by the Tauber Foundation and the Valya and Robert Shapiro Endowment. For the complete list of books that are available in this series, please see www.upne.com Noam Zadoff Gershom Scholem: From Berlin to Jerusalem and Back *Monika Schwarz-Friesel and Jehuda Reinharz Inside the Antisemitic Mind: The Language of Jew-Hatred in Contemporary Germany Elana Shapira Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna ChaeRan Y. Freeze, Sylvia Fuks Fried, and Eugene R. Sheppard, editors The Individual in History: Essays in Honor of Jehuda Reinharz Immanuel Etkes Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liady: The Origins of Chabad Hasidism *Robert Nemes and Daniel Unowsky, editors Sites of European Antisemitism in the Age of Mass Politics, 1880–1918 Sven-Erik Rose Jewish Philosophical Politics in Germany, 1789–1848 ChaeRan Y. -

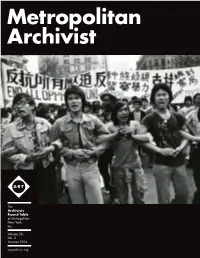

The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014

Metropolitan Archivist The Archivists Round Table of Metropolitan New York, Inc. Volume 20, No. 2 Summer 2014 nycarchivists.org Welcome! The following individuals have joined the Archivists Round Table We extend a special thank you to the following of Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) from January 2014 to June 2014 members for their support as A.R.T. Sustaining Members: Gaetano F. Bello, Corrinne Collett, New Members Anthony Cucchiara, Constance de Ropp, Barbara John Brokaw Haws, Chris Lacinak, Sharon Lehner, Liz Kent Cynthia Brenwall León, Alice Merchant, Sanford Santacroce Maureen Callahan The Michael Carter Thank you to our Sponsorship Members: Archivists Celestina Cuadrado Ann Butler, Frank Caputo, Linda Edgerly, Chris Round Table of Metropolitan Jacqueline DeQuinzio Genao, Celia Hartmann, David Kay, Stephen New York, Elizabeth Fox-Corbett Perkins, Marilyn H. Pettit, Alix Ross, Craig Savino Inc. Tess Hartman-Cullen Carmen Lopez The mission of Metropolitan Archivist is to Sam Markham serve members of the Archivists Round Table of Volume 20, Brian Meacham Metropolitan New York, Inc. (A.R.T.) by: No. 2 Chloe Pfendler - Informing them of A.R.T. activities through Summer 2014 David Rose reports of monthly meetings and committee Angela Salisbury activities nycarchivists.org Natalia Sucre - Relating important announcements about Marissa Vassari individual members and member repositories - Reporting important news related to the New York Board of Directors New Student Members metropolitan area archival profession Pamela Cruz Carlos Acevado - Providing a forum to discuss archival issues President Elizabeth Berg Ryan Anthony Thomas Cleary Metropolitan Archivist (ISSN 1546-3125) is Donaldson Vice President Rina Eisenberg issued semi-annually to the members of A.R.T. -

Returning Looted European Library Collections: an Historical Analysis of the Offenbach Archival Depot, 1945–1948

Anne Rothfeld1 RETURNING LOOTED EUROPEAN LIBRARY COLLECTIONS: AN HISTORICAL ANALYSIS OF THE OFFENBACH ARCHIVAL DEPOT, 1945–1948 In 1944, Pierce Butler wrote, “ever since libraries have existed, war has been one of the chief agencies of [their] annihilation.”2 The looting and destruction of cultural treasures during wartime is an established fact throughout Western history, including Greek and Roman times as well as during the Crusades, when empires stripped defeated nations of their cultural heritage. During the Napoleonic Wars in the early nineteenth century, Napoleon had an army of art commissioners who were ordered to locate and seize valuable cultural property, including whole libraries, for transfer to France. But the systematic Nazi confiscation of European cultural treasures in the twentieth century was unique, as looting at- tained new ideological and methodological dimensions that furthered the Nazi goals of destroying whole peoples and cultures. Despite recent publicity on the restitution of Nazi stolen artworks, the seizure and destruction of European library collections receives little attention today. But this was certainly not the case just after the end of the war. Recognizing the massive looting that had transpired, the Allies set up the largest book restitution program in history, a program that can justly be described as the antithesis to the German plundering machine. In March 1946, the Allied Military occupation government of Germany established the Offenbach Archival Depot, and placed it under the supervision of the Monuments, Fine Arts, & Archives program (MFA&A), a branch of the Office of Military Government in Germany and Austria. The task of the men assigned to the program—young historians, museum curators, librarians, and archivists—was to recover, 1. -

Israeli Chapter, While Additions in the United States and the Netherlands Bring the Total Coverage to Over 35 Repositories

RECONSTRUCTING THE RECORD OF NAZI CULTURAL PLUNDER A GUIDE TO THE DISPERSED ARCHIVES OF THE EINSATZSTAB REICHSLEITER ROSENBERG (ERR) AND THE POSTWAR RETRIEVAL OF ERR LOOT Patricia Kennedy Grimsted Expanded and Updated Edition Published on-line with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), in association with the International Institute of Social History (IISH), Amsterdam, and the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam © Copyright 2015, Patricia Kennedy Grimsted The original volume was initially published as: Reconstructing the Record of Nazi Cultural Plunder: A Survey of the Dispersed Archives of the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), IISH Research Paper 47, by the International Institute of Social History (IISH), in association with the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Amsterdam, and with generous support of the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany (Claims Conference), Amsterdam, March 2011. The entire original 2011 volume and country chapters are available in free PDF files at: http://socialhistory.org/en/publications/reconstructing-record-nazi-cultural-plunder. Also now available at http://www.errproject.org is the updated Introduction: “Alfred Rosenberg and the ERR: The Records of Plunder and the Fate of Its Loot” (LAST REVISED August 2015) Chapter 6 (earlier Ch. 5): The Netherlands (LAST REVISED October 2015) and Chapter 10 (earlier Ch. 9): United States of America (LAST REVISED March 2015) Other updated country chapters will be available as completed at: http://www.errproject.org/guide The Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg (ERR), the special operational task force headed by Adolf Hitler’s leading ideologue Alfred Rosenberg, was the major NSDAP agency engaged in looting cultural valuables in Nazi-occupied countries during the Second World War.