Nazi-Confiscated Art Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE LATE RENAISSANCE and MANNERISM in SIXTEENTH-CENTURY ITALY 591 17 CH17 P590-623.Qxp 4/12/09 15:24 Page 592

17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:24 Page 590 17_CH17_P590-623.qxp 12/10/09 09:25 Page 591 CHAPTER 17 CHAPTER The Late Renaissance and Mannerism in Sixteenth- Century Italy ROMTHEMOMENTTHATMARTINLUTHERPOSTEDHISCHALLENGE to the Roman Catholic Church in Wittenberg in 1517, the political and cultural landscape of Europe began to change. Europe s ostensible religious F unity was fractured as entire regions left the Catholic fold. The great powers of France, Spain, and Germany warred with each other on the Italian peninsula, even as the Turkish expansion into Europe threatened Habsburgs; three years later, Charles V was crowned Holy all. The spiritual challenge of the Reformation and the rise of Roman emperor in Bologna. His presence in Italy had important powerful courts affected Italian artists in this period by changing repercussions: In 1530, he overthrew the reestablished Republic the climate in which they worked and the nature of their patron- of Florence and restored the Medici to power. Cosimo I de age. No single style dominated the sixteenth century in Italy, Medici became duke of Florence in 1537 and grand duke of though all the artists working in what is conventionally called the Tuscany in 1569. Charles also promoted the rule of the Gonzaga Late Renaissance were profoundly affected by the achievements of Mantua and awarded a knighthood to Titian. He and his suc- of the High Renaissance. cessors became avid patrons of Titian, spreading the influence and The authority of the generation of the High Renaissance prestige of Italian Renaissance style throughout Europe. would both challenge and nourish later generations of artists. -

List of Participants

JUNE 26–30, Prague • Andrzej Kremer, Delegation of Poland, Poland List of Participants • Andrzej Relidzynski, Delegation of Poland, Poland • Angeles Gutiérrez, Delegation of Spain, Spain • Aba Dunner, Conference of European Rabbis, • Angelika Enderlein, Bundesamt für zentrale United Kingdom Dienste und offene Vermögensfragen, Germany • Abraham Biderman, Delegation of USA, USA • Anghel Daniel, Delegation of Romania, Romania • Adam Brown, Kaldi Foundation, USA • Ann Lewis, Delegation of USA, USA • Adrianus Van den Berg, Delegation of • Anna Janištinová, Czech Republic the Netherlands, The Netherlands • Anna Lehmann, Commission for Looted Art in • Agnes Peresztegi, Commission for Art Recovery, Europe, Germany Hungary • Anna Rubin, Delegation of USA, USA • Aharon Mor, Delegation of Israel, Israel • Anne Georgeon-Liskenne, Direction des • Achilleas Antoniades, Delegation of Cyprus, Cyprus Archives du ministère des Affaires étrangères et • Aino Lepik von Wirén, Delegation of Estonia, européennes, France Estonia • Anne Rees, Delegation of United Kingdom, United • Alain Goldschläger, Delegation of Canada, Canada Kingdom • Alberto Senderey, American Jewish Joint • Anne Webber, Commission for Looted Art in Europe, Distribution Committee, Argentina United Kingdom • Aleksandar Heina, Delegation of Croatia, Croatia • Anne-Marie Revcolevschi, Delegation of France, • Aleksandar Necak, Federation of Jewish France Communities in Serbia, Serbia • Arda Scholte, Delegation of the Netherlands, The • Aleksandar Pejovic, Delegation of Monetenegro, Netherlands -

TEL AVIV PANTONE 425U Gris PANTONE 653C Bleu Bleu PANTONE 653 C

ART MODERNE ET CONTEMPORAIN TRIPLEX PARIS - NEW YORK TEL AVIV Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U Bleu PANTONE 653 C Gris PANTONE 425 U ART MODERNE et CONTEMPORAIN Ecole de Paris Tableaux, dessins et sculptures Le Mardi 19 Juin 2012 à 19h. 5, Avenue d’Eylau 75116 Paris Expositions privées: Lundi 18 juin de 10 h. à 18h. Mardi 19 juin de 10h. à 15h. 5, Avenue d’ Eylau 75116 Paris Expert pour les tableaux: Cécile RITZENTHALER Tel: +33 (0) 6 85 07 00 36 [email protected] Assistée d’Alix PIGNON-HERIARD Tel: +33 (0) 1 47 27 76 72 Fax: 33 (0) 1 47 27 70 89 [email protected] EXPERTISES SUR RDV ESTIMATIONS CONDITIONS REPORTS ORDRES D’ACHAt RESERVATION DE PLACES Catalogue en ligne sur notre site www.millon-associes.com בס’’ד MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY FINE ART NEW YORK : Tuesday, June 19, 2012 1 pm TEL AV IV : Tuesday, 19 June 2012 20:00 PARIS : Mardi, 19 Juin 2012 19h AUCTION MATSART USA 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY 10019 PREVIEW IN NEW YORK 444 W. 55th St. New York, NY. 10019 tel. +1-347-705-9820 Thursday June 14 6-8 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 5 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 5 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 5 pm Other times by appointment: 1 347 705 9820 PREVIEW AND SALES ROOM IN TEL AVIV 15 Frishman St., Tel Aviv +972-2-6251049 Thursday June 14 6-10 pm opening reception Friday June 15 11 am – 3 pm Saturday June 16 closed Sunday June 17 11 am – 6 pm Monday June 18 11 am – 6 pm tuesday June 19 (auction day) 11 am – 2 pm Bleu PREVIEW ANDPANTONE 653 C SALES ROOM IN PARIS Gris 5, avenuePANTONE d’Eylau, 425 U 75016 Paris Monday 18 June 10 am – 6 pm tuesday 19 June 10 am – 3 pm live Auction 123 will be held simultaneously bid worldwide and selected items will be exhibited www.artonline.com at each of three locations as noted in the catalog. -

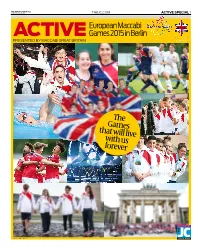

The Games That Will Live with Us Forever

THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 1 European Maccabi ACTIVE Games 2015 in Berlin PRESENTED BY MACCABI GREAT BRITAIN The Games that will live with us forever MEDIA partner PHOTOS: MARC MORRIS THE JEWISH CHRONICLE THE JEWISH CHRONICLE 2 ACTIVE SPECIAL THEJC.COM 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 18 SEPTEMBER 2015 THEJC.COM ACTIVE SPECIAL 3 ALL ALL WORDS PHOTOS WELCOME BY DAnnY BY MARC CARO MORRIS Maccabi movement’s ‘miracle’ in Berlin LDN Investments are proud to be associated with Maccabi GB and the success of the European Maccabi Games in Berlin. HIS SUMMER, old; athletes and their families; reuniting THE MACCABI SPIRIT place where they were banished from first night at the GB/USA Gala Dinner, “By SOMETHING hap- existing friendships and creating those Despite the obvious emotion of the participating in sport under Hitler’s winning medals we have not won. By pened which had anew. Friendships that will last a lifetime. Opening Ceremony, the European Mac- reign was a thrill and it gave me an just being here in Berlin we have won.” never occurred But there was also something dif- cabi Games 2015 was one big party, one enormous sense of pride. We will spread the word, keep the before. For the first ferent about these Games – something enormous celebration of life and of Having been there for a couple of days, torch of love, not hate, burning bright. time in history, the that no other EMG has had before it. good triumphing over evil. Many thou- my hate of Berlin turned to wonder. -

The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Fall 1-5-2021 The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 Denali Elizabeth Kemper CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/661 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Fate of National Socialist Visual Culture: Iconoclasm, Censorship, and Preservation in Germany, 1945–2020 By Denali Elizabeth Kemper Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2020 Thesis sponsor: January 5, 2021____ Emily Braun_________________________ Date Signature January 5, 2021____ Joachim Pissarro______________________ Date Signature Table of Contents Acronyms i List of Illustrations ii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Points of Reckoning 14 Chapter 2: The Generational Shift 41 Chapter 3: The Return of the Repressed 63 Chapter 4: The Power of Nazi Images 74 Bibliography 93 Illustrations 101 i Acronyms CCP = Central Collecting Points FRG = Federal Republic of Germany, West Germany GDK = Grosse Deutsche Kunstaustellung (Great German Art Exhibitions) GDR = German Democratic Republic, East Germany HDK = Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) MFAA = Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives Program NSDAP = Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Worker’s or Nazi Party) SS = Schutzstaffel, a former paramilitary organization in Nazi Germany ii List of Illustrations Figure 1: Anonymous photographer. -

Francesca Coccolo, Rodolfo Siviero Between Fascism and the Cold

STUDI DI MEMOFONTE Rivista on-line semestrale Numero 22/2019 FONDAZIONE MEMOFONTE Studio per l’elaborazione informatica delle fonti storico-artistiche www.memofonte.it COMITATO REDAZIONALE Proprietario Fondazione Memofonte onlus Fondatrice Paola Barocchi Direzione scientifica Donata Levi Comitato scientifico Francesco Caglioti, Barbara Cinelli, Flavio Fergonzi, Margaret Haines, Donata Levi, Nicoletta Maraschio, Carmelo Occhipinti Cura scientifica Daria Brasca, Christian Fuhrmeister, Emanuele Pellegrini Cura redazionale Martina Nastasi, Laurence Connell Segreteria di redazione Fondazione Memofonte onlus, via de’ Coverelli 2/4, 50125 Firenze [email protected] ISSN 2038-0488 INDICE The Transfer of Jewish-owned Cultural Objects in the Alpe Adria Region DARIA BRASCA, CHRISTIAN FUHRMEISTER, EMANUELE PELLEGRINI Introduction p. 1 VICTORIA REED Museum Acquisitions in the Era of the Washington Principles: Porcelain from the Emma Budge Estate p. 9 GISÈLE LÉVY Looting Jewish Heritage in the Alpe Adria Region. Findings from the Union of the Italian Jewish Communities (UCEI) Historical Archives p. 28 IVA PASINI TRŽEC Contentious Musealisation Process(es) of Jewish Art Collections in Croatia p. 41 DARIJA ALUJEVIĆ Jewish-owned Art Collections in Zagreb: The Destiny of the Robert Deutsch Maceljski Collection p. 50 ANTONIJA MLIKOTA The Destiny of the Tilla Durieux Collection after its Transfer from Berlin to Zagreb p. 64 DARIA BRASCA The Dispossession of Italian Jews: the Fate of Cultural Property in the Alpe Adria Region during Second World War p. 79 CAMILLA DA DALT The Case of Morpurgo De Nilma’s Art Collection in Trieste: from a Jewish Legacy to a ‘German Donation’ p. 107 CRISTINA CUDICIO The Dissolution of a Jewish Collection: the Pincherle Family in Trieste p. -

Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - a Defense

DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law Volume 23 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Article 2 Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - A Defense Simon J. Frankel Ethan Forrest Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip Recommended Citation Simon J. Frankel & Ethan Forrest, Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion of Statutes of Limitations in Response to Nazi-Era Art Restitution Claims - A Defense, 23 DePaul J. Art, Tech. & Intell. Prop. L. 279 (2013) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jatip/vol23/iss2/2 This Lead Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal of Art, Technology & Intellectual Property Law by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frankel and Forrest: Museums' Initiation of Declaratory Judgment Actions and Assertion MUSEUMS' INITIATION OF DECLARATORY JUDGMENT ACTIONS AND ASSERTION OF STATUTES OF LIMITATIONS IN RESPONSE TO NAZI-ERA ART RESTITUTION CLAIMS-A DEFENSE Simon J. Frankel and Ethan Forrest* ABSTRACT Since the reunification of Germany brought greater access to information about the history and location of artworks that changed hands during the Nazi era, numerous restitution claims have been asserted to works held by U.S. museums. In a few instances, U.S. museums faced with such claims have initiated declaratoryjudgment actions seeking to quiet title to the works and have also invoked statutes of limitations or laches to bar the claims. -

Mapping the Limits of Repatriable Cultural Heritage: a Case Study of Stolen Flemish Art in French Museums

_________________ COMMENT _________________ MAPPING THE LIMITS OF REPATRIABLE CULTURAL HERITAGE: A CASE STUDY OF STOLEN FLEMISH ART IN FRENCH MUSEUMS † PAIGE S. GOODWIN INTRODUCTION......................................................................................674 I. THE NAPOLEONIC REVOLUTION AND THE CREATION OF FRANCE’S MUSEUMS ................................................676 A. Napoleon and the Confiscation of Art at Home and Abroad.....677 B. The Second Treaty of Paris ....................................................679 II. DEVELOPMENT OF THE LAW OF RESTITUTION ...............................682 A. Looting and War: From Prize Law to Nationalism and Cultural-Property Internationalism .................................682 B. Methods of Restitution Today: Comparative Examples............685 1. The Elgin Marbles and the Problem of Cultural-Property Internationalism........................687 2. The Italy-Met Accord as a Restitution Blueprint ...689 III. RESTITUTION OF FLEMISH ART AND POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS IN PUBLIC AND PRIVATE LAW .........................................................692 A. Why Should France Return Flemish Art Now?.........................692 1. Nationalism .............................................................692 2. Morality and Legality ..............................................693 3. Universalism............................................................694 † J.D. Candidate, 2009, University of Pennsylvania Law School; A.B., 2006, Duke Uni- versity. Many thanks to Professors Hans J. Van Miegroet -

Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann's German

documenta studies #11 December 2020 NANNE BUURMAN Northern Gothic: Werner Haftmann’s German Lessons, or A Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction This essay by the documenta and exhibition scholar Nanne Buurman I See documenta: Curating the History of the Present, ed. by Nanne Buurman and Dorothee Richter, special traces the discursive tropes of nationalist art history in narratives on issue, OnCurating, no. 13 (June 2017). German pre- and postwar modernism. In Buurman’s “Ghost (Hi)Story of Abstraction” we encounter specters from the past who swept their connections to Nazism under the rug after 1945, but could not get rid of them. She shows how they haunt art history, theory, the German feuilleton, and even the critical German postwar literature. The editor of documenta studies, which we founded together with Carina Herring and Ina Wudtke in 2018, follows these ghosts from the history of German art and probes historical continuities across the decades flanking World War II, which she brings to the fore even where they still remain implicit. Buurman, who also coedited the volume documenta: Curating the History of the Present (2017),I thus uses her own contribution to documenta studies to call attention to the ongoing relevance of these historical issues for our contemporary practices. Let’s consider the Nazi exhibition of so-called Degenerate Art, presented in various German cities between 1937 and 1941, which is often regarded as documenta’s negative foil. To briefly recall the facts: The exhibition brought together more than 650 works by important artists of its time, with the sole aim of stigmatizing them and placing them in the context of the Nazis’ antisemitic racial ideology. -

Copies of Artworks the Case of Paintings and Prints* Françoise

Copies of Artworks The Case of Paintings and Prints* Françoise Benhamou Université de Rouen and MATISSE, Université de Paris I and Victor Ginsburgh ECARES, Université Libre de Bruxelles and CORE, Université catholique de Louvain January 2005 Abstract * The paper freely draws on our previous (2001) paper. We are grateful to M. Aarts, Me Cornette de St. Cyr, M. Cornu, D. Delamarre, M. Fouado-Otsuka, Me Lelorier, T. Lenain, M. Melot, O. Meslay, D. Schulmann, B. Steyaert, G. Touzenis, H. Verschuur and S. Weyers for very useful conversations and comments. Neil De Marchi's very careful comments on a preliminary version of the paper at the Princeton Conference led to several changes. We also thank Alvin Huisman (2001) who collected data on auctions 1976-1999. The second author acknowledges financial support from Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique. 1 "We use copies to certify originals, originals to certify copies, then we stand bewildered." Hillel Schwartz Research on copies is essentially focused on industrial activities (books, records, fashion, protection of patents) and on the incentives or disincentives to creativity resulting from copyright.1 But copies are also linked to questions concerned with value, the allocation of property rights, and regulation, three central questions in economics. In his essay on imitation in the arts, Adam Smith (1795) considers that the exact copy of an artwork always deserves less merit than the original.2 But the hierarchy between copies and originals has changed over time. So has the perception of copies by lawyers, philosophers, art historians and curators. The observation of these changes can be used to analyze art tastes and practices. -

Technological Studies Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Technological Studies Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna CONSERVATION – RESTORATION – RESEARCH – TECHNOLOGY Special volume: Storage Vienna, 2015 Technological Studies Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna Special volume: Storage Vienna, 2015 Technological Studies Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna CONSERVATION – RESTORATION – RESEARCH – TECHNOLOGY Special volume: Storage Vienna, 2015 Translated from the German volume: Content Technologische Studien Kunsthistorisches Museum. Konservierung – Restaurierung – Forschung – Technologie, Sonderband Depot, Band 9/10, Wien 2012/13 PREFACE Sabine Haag and Paul Frey 6 Editor: Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna INTRODUCTION Martina Griesser, Alfons Huber and Elke Oberthaler 7 Sabine Haag Editorial Office: ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9 Martina Griesser, Alfons Huber, Elke Oberthaler Assistant, Editorial Office: ESSAYS Stefan Fleck Building a Cost-Effective Art Storage Facility that 13 Tanja Kimmel maintains State-of-the-Art Requirements Joachim Huber Creating a Quantity Structure for Planning Storage 21 Translations: Equipment in Museum Storage Areas Aimée Ducey-Gessner, Emily Schwedersky, Matthew Hayes (Summaries) Christina Schaaf-Fundneider and Tanja Kimmel Relocation of the 29 Collections of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna to the New Art Direction: Central Storage Facility: Preparation, Planning, and Implementation Stefan Zeisler Pascal Querner, Tanja Kimmel, Stefan Fleck, Eva Götz, Michaela 63 Photography: Morelli and Katja Sterflinger Integrated Pest Management (IPM) Christian Mendez, Thomas Ritter, Alexander Rosoli, -

Lucy S. Dawidowicz and the Restitution of Jewish Cultural Property

/XF\6'DZLGRZLF]DQGWKH5HVWLWXWLRQRI-HZLVK&XOWXUDO 3URSHUW\ 1DQF\6LQNRII American Jewish History, Volume 100, Number 1, January 2016, pp. 117-147 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/ajh.2016.0009 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ajh/summary/v100/100.1.sinkoff.html Access provided by Rutgers University (20 Jan 2016 03:00 GMT) From the Archives: Lucy S. Dawidowicz and the Restitution of Jewish Cultural Property NANCY SINKOFF1 In September of 1946, Lucy Schildkret, who later in life would earn renown under her married name, Lucy S. Dawidowicz,2 as an “inten- tionalist” historian of the Holocaust,3 sailed to Europe to work for the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (the JDC, the Joint, or the AJDC) in its overseas educational department among Jewish refugees in displaced persons (DP) camps.4 She later recalled that the journey had filled her with foreboding.5 Schildkret was returning to a Europe 1. I would like to thank David Fishman, Dana Herman, and the anonymous readers of American Jewish History for comments on earlier versions of this article. 2. I use the name Lucy Schildkret for anything she wrote prior to her marriage to Szymon Dawidowicz in January of 1948, Lucy S. Dawidowicz after her marriage, and Libe when she or her correspondents wrote in Yiddish. 3. The literature on “intentionalism” — the view that German antisemitism laid the foundation for Hitler’s early and then inexorable design to exterminate European Jewry — is enormous. See Omer Bartov, Germany’s War and the Holocaust: Disputed Histories (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2003), 80–81; Michael R.