Washington DC MSA Urban Density

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Arlington Profile

Department of Community Planning, Housing, and Development PROFILE 2020 2020 Profile 2020 Contents Message from the Director 1 Fast Facts The Profile, an annual statistical fact book of Arlington County, has been produced by the Department of 2 Land Use & Development Community Planning, Housing, and Development 3 Population (CPHD) since 1982. This report combines countywide data and provides a comprehensive outlook of 5 Housing the most current data on population, housing, 7 Households employment, development, transportation, and community services. The Profile data are used to 9 Employment obtain an understanding of our community; for 11 Development planning future services and needs; to guide policy decisions; and to secure grant funding. 13 Schools & Education 15 Multi-Modal Transportation COVID-19 has had an immense impact on our daily lives. Profile 2020 is exceptionally important and 17 Community Services & Resources considered as a benchmark year. Statistics found in 18 Health & Wellness Services this document can be used as a baseline to measure changes that may have occurred since early 2020. 19 Forecast 21 Glossary Profile 2020 continues to include statistics from across departments. New this year, Arlington Public Library statistics highlight the number of library programs, services, and constituents served. Did you know that 47% of Arlington households are active library patrons? Find out more about libraries on page 17. In addition to the Profile 2020 report, an interactive Planning Corridors visualization tool is available Arlington County Vision on the profile webpage (arlingtonva.us/profile) and supports the comparison of demographics across the Rosslyn-Ballston, Richmond Highway, and Columbia “Arlington will be a diverse Pike Corridors with the rest of the County. -

Indicators of Success and Challenges in Northern Virginia Northern Virginia Is a Diverse, Growing Region with a Well-Educated Population and Strong Economy

Indicators of Success and Challenges in Northern Virginia Northern Virginia is a diverse, growing region with a well-educated population and strong economy. However, with this success comes challenges such as high CONTENTS housing costs and long commutes that hit low-income residents particularly hard. 1 about the opportunity index The region--Arlington County, Alexandria City, Falls Church City, Fairfax County, 2 general demographics Fairfax City, Loudoun County, Manassas City, Manassas Park City, and Prince William 11 economy County--also continues to be heavily dependent on federal employment, both 19 education directly and through federal contracts. And despite some success in narrowing 25 community health & civic life educational achievement gaps, Black and Hispanic/Latino residents of the region 36 moving forward continue to have higher unemployment and poverty rates, lower household incomes, and lower rates of health insurance access than their non-Hispanic White and Asian peers in the region. In conjunction with the Community ABOUT THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FOR Foundation’s 40th Anniversary, it NORTHERN VIRGINIA commissioned this report from The Commonwealth Institute to gain some The Community Foundation for Northern Virginia is a visionary perspective on changes and growth in funder that has directed millions of charitable dollars to our region over the past 40 years, and people in need since 1978. Its mission is to grow philanthropy to provide insight into current trends to respond to critical need and seed innovation in our region. that will help guide its future work to Serving all of Northern Virginia, including Arlington, Fairfax, make the greatest impact in responding Loudoun and Prince William Counties and the cities of to critical need and seeding innovation. -

Arlington Profile 2018

PROFILE2018 HISTORY ARLINGTON IN THE DC METRO AREA Arlington is an urban county of about 26 square miles located directly across the Potomac River from Washington DC. No MARYLAND 5 C 9 4 A - P incorporated towns or cities lie within I I T Montgomery A L County District of Arlington’s boundaries. B E Y Columbia L A I-295 T W W T Fairfax A Originally part of the area surveyed for L E Y County B I L the nation’s capital, the portion of the - Prince 9 A 5 T I / P Georges I - District on the west bank of the Potomac A 4 C Arlington County 9 Falls 5 River was returned to the Commonwealth I-66 Church of Virginia by the U.S. Congress in 1846. County This area was known as Alexandria City VIRGINIA and Alexandria County until 1920 when RIVER POTOMAC the county portion was renamed Arlington Alexandria I-395 County. Metrorail Stop DEMOGRAPHICS As of January 1, 2018, Arlington had an estimated population of 225,200, reflecting an increase of 8.5% since 2010. On average, Arlington’s population has grown at about 1% per year since 2000. Arlington County population estimates are based on housing unit counts and residential construction activity, which is closely monitored for changes and reported quarterly through the County’s development tracking reports. The U.S. Census Bureau also produces estimates at the county level that are higher due in part to the population migration methodology utilized by the U.S. Census Bureau. Historically, Arlington County’s estimates are closer than the Census Bureau’s estimates to the actual Decennial Census counts. -

Building Northern Virginia's Future

Building Northern Virginia’s Future: Policies to Create a More Affordable, Equitable Housing Supply JANUARY 2019 A Letter from the Executive Director Transportation, housing opportunities at all price points, and a skilled workforce are acknowledged as the key elements of a ‘three-legged stool’ that support regional economic prosperity in the Washington metropolitan region. In the spring of 2018, the region entered into a landmark agreement to provide dedicated funding for Metro. Since that time, regional advocates have turned their attention to housing supply and affordability. In September 2018, the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (COG) released a report showing that the Washington region must increase the number of planned housing units by over 100,000 homes between now and 2045 ‘to sustain economic growth and improve quality of life.’ As Robert White, the newly elected Chairman of the COG Board of Directors stated: “I can think of no higher regional priority than to ensure a sufficient supply of affordably-priced housing for our current residents as well as the workers we need to fill the new jobs anticipated in the future.” Building Northern Virginia’s Future: Policies to Create a More Affordable, Equitable Housing Supply is the latest in a series of studies released by the Northern Virginia Affordable Housing Alliance to address specific housing challenges facing our region. Our report shows that after keeping pace with population growth from 1990-2010, housing production in the inner region of Washington, DC significantly lagged population growth from 2010-2016 – 7.0% population growth vs. 2.7% housing units. A number of factors have contributed to this under-performing market, namely: lengthy site planning processes; more restrictive zoning regulations; and a shortage of skilled construction labor. -

Northern Virginia Health and Wellness Directory

Northern Virginia Health and Wellness Directory 2012 Northern Virginia Health Foundation 1940 Duke Street Suite 200 Alexandria, VA 22314 (703) 486-5691 (703) 486-5692 fax www.novahealthfdn.org Table of Contents Abuse and Neglect Page 1 Disabilities Page 12 Disease Prevention & Management Page 23 General Wellness & Education Page 39 Mental Health Page 47 Nutrition Page 63 Oral Health Page 73 Parenting & Infant Health Page 76 Physical Fitness Page 88 Smoking & Tobacco Cessation Page 93 Substance Abuse Page 95 Supportive Services Page 97 Indexes Organization/Agency Name Page 101 Topics and Target populations Page 104 NORTHERN VIRGINIA HEALTH FOUNDATION NOVAHEALTHFDN.ORG About This Directory The Northern Virginia Health Foundation developed this Health and Wellness Directory, which was first published in 2010, as a resource for all who share our vision of a community with the capacity to be and stay healthy. In times of great economic uncertainty and demographic change, Northern Virginia is under tremendous pressure to offer the most efficient and accessible health and wellness programs. We hope this directory facilitates and supports strategic partnerships and key alliances among these and other groups. And we hope that the groups listed will use this information to direct their clients to additional resources which they may need. The Foundation invited nonprofit organizations and government agencies that offer health and wellness programs in Northern Virginia to submit information for inclusion in this directory. Our goal was to identify community-based programs that work with individuals and groups in one or more of the following ways: Adopting healthy behaviors and/or reducing health risks Increasing self-care skills Improving management of common ailments Using health care services more effectively and/or improving understanding of medical procedures and therapeutic regimens We only included programs located in and serving Northern Virginia, operating under the auspices of a nonprofit or government agency and open to the public. -

THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE of VIRGINIA Richmond, Virginia

THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF VIRGINIA Richmond, Virginia MISSIONER FOR RACIAL JUSTICE AND HEALING Anticipated Start Date: Summer/Fall 2021 thediocese.net DIOCESAN VISION Our eyes fixed on Jesus, we speak the truth and act in love for the transforming of lives and healing of the world. We live this vision especially in: Racial Justice and Healing Care of God’s Creation Sharing the Faith of Jesus OVERVIEW The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia is a community of more than 68,000 members and 425 clergy in central, northern, and northwestern Virginia. Organized in 1785, the Diocese serves the world through 179 congregations, six schools, six diocesan retirement homes, two diocesan retreat centers, and is home to the largest Anglican seminary in the world. The Diocese of Virginia seeks an experienced organizational leader to serve as its Missioner for Racial Justice and Healing starting summer or fall of 2021. The Missioner will engage and support the congregations, organizations, and institutions of the Diocese in dismantling racism through programs and activities that help it name and overcome past and present legacies of slavery, colonialism, white supremacy, white privilege, and racial injustice. The Missioner for Racial Justice and Healing will be both skilled and passionate about the work, supporting existing ministries of racial justice, developing new ministries, and fostering healing across racial and other divides. The successful candidate will primarily work at the diocesan offices in Richmond, Virginia, traveling throughout the Diocese as needed. The position is open to clergy and lay persons. ABOUT THE EPISCOPAL DIOCESE OF VIRGINIA The Episcopal Diocese of Virginia was organized in May 1785 and was one of nine dioceses represented at the first General Convention in September 1785, which brought together the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America. -

Preliminary Research of Free Black in Loudoun County, Virginia 1850-1860 Identity, Settlement Patterns and Cultural Landscape SC

Collection SC 0033 Preliminary Research of Free Blacks in Loudoun County, Virginia 1850-1860: Identity, Settlement Patterns and Cultural Landscape 1850-1866, 2004 Table of Contents User Information Biographical Sketch Scope and Content Note Container List Processed by Matthew Exline 5 Feb 2008 Thomas Balch Library 208 W. Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 USER INFORMATION VOLUME OF COLLECTION: 6 Folders. COLLECTION DATES: 1850-1866, 2004 PROVENANCE: Janine Duncan, GA. ACCESS RESTRICTIONS: Open for research. USE RESTRICTIONS: No physical characteristics affect use of this material. REPRODUCTION RIGHTS: Permission to reproduce or publish material in this collection must be obtained in writing from Thomas Balch Library. CITE AS: Preliminary Research of Free Blacks in Loudoun County, Virginia 1850-1860 (SC 0033), Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. ALTERNATE FORMATS: None OTHER FINDING AIDS: None RELATED HOLDINGS: Black Laws of Virginia: a summary of the legislative acts of Virginia concerning Negroes from earliest times to the present, by June Purcell Guild, compiled by Karen Hughes White and Joan Peters, REF 348.755 GUI; I Do Hereby Certify…a Register of free negroes of Loudoun County, Virginia from 1793-1861, transcribed and compiled by Victoria J. Robinson, REF 973.0496 ROB; Abstracts of Loudoun County, Virginia: register of free negroes, 1844- 1861, by Patricia B. Duncan, REF 929.375528 DUN; Loudoun County, Virginia lists of free negroes: 1851, 1855, 1856, 1857, 1858, 1859, copied by Townsend M. Lucas, REF 301.451 LUC; Loudoun County, Virginia numbered certificates of Free Negroes, copied by Townsend M. Lucas, REF 301.451 LUC; Free Negroes in Northern Virginia: an investigation of the growth and status of free Negroes in the counties of Alexandria, Fairfax and Loudoun, 1770-1860, by Donald M. -

Virginia PRO Act Survey Release

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release: June 29, 2021 Contact Bonnie Taylor 703.297.8554 Survey: Virginia Voters Concerned About PRO Act And Its Impact On Workers’ Rights And Small Business Nearly eight in 10 voters concerned about federal legislation repealing Virginia’s right-to-work laws, forcing workers to pay union dues or risk losing their job. Seven in 10 voters concerned about privacy issues and negative impacts on small businesses and in- dependent contractors. Fairfax, VA – A new statewide survey shows Virginia voters have serious concerns regarding the Protecting Right to Organize (PRO) Act and the impact the federal legislation would have on workers’ rights and small business if enacted by Congress. Virginia voters are most concerned that the PRO Act, which would drastically rewrite labor regulations in the U.S. and repeal Virginia’s right-to-work laws, would force employees to join a union and pay dues to retain their job, turn over employees’ personal information to union organizers, negatively impact small businesses and put inde- pendent contractors out of work. Northern Virginia Chamber President and CEO Julie Coons said the survey aligns with the concerns of employ- ees and employers throughout the state: “This year has taken a toll on Virginia’s workers and small businesses. The PRO Act that would repeal our right- to-work law and force Virginians to pay union dues as a condition of employment. Doing so would do irreparable harm to Virginia’s ability to attract new businesses, permanently damaging our economy,” Ms. Coons said. “This survey shows that voters share these concerns and do not support radically changing labor laws at the expense of Virginia workers and businesses.” Ms. -

Northern Virginia District Highlights

Northern Virginia District Highlights We are the Commonwealth’s advocate for promoting transportation options to the general public, businesses, and community decision makers. The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation (DRPT) is a state agency that reports to the Secretary of Transportation. DRPT’s mission is to facilitate and improve the mobility of Virginia citizens and to promote the efficient transport of goods and people in a safe, reliable, and cost‐effective manner. Our primary areas of activity are rail, public transportation, and commuter services. DRPT works with local, regional, state, and federal governments, as well as private entities, to provide support for projects and programs by: Conducting Planning and Providing Assessing feasibility statewide rail and programming new leadership, and environmental public services and capital advocacy, technical impacts of new and transportation improvement assistance, and expanding services studies projects funding Below are summaries of ongoing projects and funding allocations in the proposed Six‐Year Improvement Program (SYIP) that support this mission in the Northern Virginia District. DRPT Fiscal Year (FY) 2019: $595 million statewide Northern Virginia District Transit: $134.3 million Rail: $28.3M Transit and Commuter Programs Organizations in the Northern Virginia District that receive state funding in FY 2019 of DRPT’s SYIP are: Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) The 2018 General Assembly passed legislation providing additional funding in the -

Future Sea Level and Recurrent Flooding Risk for Coastal Virginia

FUTURE SEA LEVEL AND RECURRENT FLOODING RISK FOR COASTAL VIRGINIA PARTNERS CCRFR Report 11 | February 2020 FUTURE SEA LEVEL AND RECURRENT FLOODING RISK FOR COASTAL VIRGINIA George M. McLeod Sheila Hutt Senior Geospatial Fellow, Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Sr. GIS Technician, Center for Geospatial Science, Education, and Analytics Flooding Resiliency Information Technology Services Asst. Director, Center for Geospatial Science, Education, and Analytics Old Dominion University Information Technology Services Old Dominion University Manuel Solano GIS Technician, Center for Geospatial Science, Education, and Analytics Dr. Thomas R. Allen Information Technology Services Program Head for Sea Level Rise and Climate Science, Institute for Old Dominion University Coastal Adaptation & Resilience Professor, Department of Political Science and Geography Kellie Burdick Old Dominion University Graduate Research Assistant, Center for Geospatial Science, Education, and Analytics Emily Steinhilber Information Technology Services Research Assistant Professor, Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Old Dominion University Flooding Resiliency Office of Research Old Dominion University Acknowledgements: This study was supported by funds from the Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency (CCRFR) and Old Dominion University’s Institute for Coastal Adaptation and Resilience (ICAR). Special thanks to Matt Pendleton and Doug Marcy of NOAA’s Office for Coastal Management for their helpful collaboration and provision of tidal surface correction data. -

Arlington County Profile

ARLINGTON COUNTY PROFILE OVERVIEW OF ARLINGTON Arlington County is located in northern Virginia, directly across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. The County encompasses 25.8 square miles of land, which was originally split off from Fairfax County in 1801 and ceded by Virginia to be included in the ten-mile square Federal District. In 1847, however, Congress allowed the land to return to the jurisdiction of Virginia following a vote in favor of retrocession by its members. This area was then known as Alexandria City and Alexandria County. In 1920, to avoid confusion, the county was renamed Arlington County. Annexation of any part of Arlington County by neighboring jurisdictions is prohibited by present law unless the entire County is annexed with the approval of County voters. There are no jurisdictions with overlapping debt or taxing powers. The water and sewage systems are operated on a self- supporting basis by the County government. Arlington’s location in the center of the Washington metropolitan region, just five minutes from Washington by car or Metrorail, has made the County a highly desirable business and residential location. Arlington has maintained high-quality residential neighborhoods while supporting well- managed growth. High-density commercial and residential development is focused around Metro stations in the Rosslyn-Ballston corridor and the Jefferson Davis corridor, which includes both Pentagon City and Crystal City. Arlington County has an estimated 2014 population of 215,000, an increase of 13.5 percent over the 2000 population. Additionally, Arlington is home to an estimated 220,600 jobs, as of January 1, 2014. -

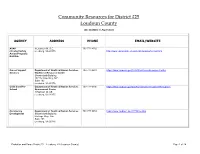

Community Resources for District #25 Loudoun County

Community Resources for District #25 Loudoun County Also Available to Supervisees AGENCY ADDRESS PHONE EMAIL/WEBSITE ASAP 9 Loudoun St. S.E. 703-771-4702 (Alcohol Safety Leesburg, VA 20175 http://www.vasap.state.va.us/locateanasap/bullrun.html Action Program) Bull Run Career Support Department of Health & Human Services 703-737-8421 https://www.loudoun.gov/1592/Workforce-Resource-Center Services Workforce Resource Center Shenandoah Building 102 Heritage Way, N.E. Suite 103 Leesburg, VA 20176 Child Care/Pre- Department of Health & Human Services 703-777-0100 https://www.loudoun.gov/2503/Child-Care-Providers-Resources School Government Center 1 Harrison St. SE Leesburg, VA 20175 Community Department of Health & Human Services 703-777-0353 https://www.loudoun.gov/1773/Housing Development Shenandoah Building Heritage Way, N.E. Suite 103 Leesburg, VA 20176 Probation and Parole District 25 – Leesburg, VA (Loudoun County) Page 1 of 24 Courts and Public Circuit Court http://www.courts.state.va.us/courts/circuit/Loudoun/home.html Records 18 East Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 E-mail: [email protected] Clerk’s Office 703-777-0270 Records Information 703-771-5243 Traffic Court 18 East Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 703-777-0312 24 Hour Info. 703-777-0310 Civil Court/Criminal Courtrooms 18 East Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 703-777-0312 Juvenile and Domestic District Court 18 East Market Street Leesburg, VA 20176 703-777-0300 Eastern Loudoun Office 45201 Research Place Suite 100 Ashburn, VA 20147 703-777-0303 Probation and Parole District 25 – Leesburg, VA (Loudoun County) Page 2 of 24 Department of Loudoun County Public Library 703-777-0368 https://library.loudoun.gov/ Library Services 102 North Street, N.W.