FY 2019 Washington Metropolitan Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Arlington Profile

Department of Community Planning, Housing, and Development PROFILE 2020 2020 Profile 2020 Contents Message from the Director 1 Fast Facts The Profile, an annual statistical fact book of Arlington County, has been produced by the Department of 2 Land Use & Development Community Planning, Housing, and Development 3 Population (CPHD) since 1982. This report combines countywide data and provides a comprehensive outlook of 5 Housing the most current data on population, housing, 7 Households employment, development, transportation, and community services. The Profile data are used to 9 Employment obtain an understanding of our community; for 11 Development planning future services and needs; to guide policy decisions; and to secure grant funding. 13 Schools & Education 15 Multi-Modal Transportation COVID-19 has had an immense impact on our daily lives. Profile 2020 is exceptionally important and 17 Community Services & Resources considered as a benchmark year. Statistics found in 18 Health & Wellness Services this document can be used as a baseline to measure changes that may have occurred since early 2020. 19 Forecast 21 Glossary Profile 2020 continues to include statistics from across departments. New this year, Arlington Public Library statistics highlight the number of library programs, services, and constituents served. Did you know that 47% of Arlington households are active library patrons? Find out more about libraries on page 17. In addition to the Profile 2020 report, an interactive Planning Corridors visualization tool is available Arlington County Vision on the profile webpage (arlingtonva.us/profile) and supports the comparison of demographics across the Rosslyn-Ballston, Richmond Highway, and Columbia “Arlington will be a diverse Pike Corridors with the rest of the County. -

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust

Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust QUARTERLY SUPPLEMENTAL DISCLOSURE (March 31, 2005) www.preit.com Pennsylvania REIT QUARTERLY SUPPLEMENTAL DISCLOSURE (March 31, 2005) Table of Contents Company Information 1 Property Development/Redevelopment Summary 19 Timeline/Recent Developments 2 Top Twenty Tenants Schedule 20 Stock Information 3 Lease Expiration Schedule - Anchor Tenants 21 Market Capitalization and Capital Resources 4 Lease Expiration Schedule - Non-Anchor Tenants 22 Balance Sheet--Wholly Owned and Partnerships Detail 5 New Lease/Renewal Summary and Analysis 23 Balance Sheet--Property Type 6 Capital Expenditures-Quarterly 24 Income Statement--Wholly Owned and Partnerships Detail -Quarterly Comparison 7 Enclosed Mall-Summary and Occupancy 25 Income Statement--Property Type- Quarterly Comparison 8 Enclosed Mall-Rent Summary 26 Income Statement--Retail (Property Status) -Quarterly Comparison 9 Power Center- Summary and Occupancy 27 Income Statement--Retail (Property Subtype) -Quarterly Comparison 10 Strip Center- Summary and Occupancy 28 FFO and FAD 11 Retail Overall- Summary and Occupancy 29 Key Ratios 12 Summary of Portfolio Services 30 Property Debt Schedule--Wholly Owned 13 Flash Report-Quarterly 31 Property Debt Schedule--Partnerships 14 Debt Analysis 15 RECONCILIATION TO GAAP: Debt Ratios 16 Balance Sheet-Reconciliation to GAAP 32 Portfolio Summary--Retail 17 Income Statement-Reconciliation to GAAP -Quarterly 33 Property Acquisitions/Dispositions- Quarterly Summary 18 Flash Report-Reconciliation to GAAP- Quarterly 34 Definitions page 35 THIS QUARTERLY SUPPLEMENTAL DISCLOSURE CONTAINS CERTAIN “FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS” THAT RELATE TO EXPECTATIONS, PROJECTIONS, ANTICIPATED EVENTS, TRENDS AND OTHER MATTERS THAT ARE NOT HISTORICAL FACTS. THESE FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS REFLECT PREIT’S CURRENT VIEWS ABOUT FUTURE EVENTS AND ARE SUBJECT TO RISKS, UNCERTAINTIES AND ASSUMPTIONS THAT MAY CAUSE FUTURE EVENTS, ACHIEVEMENTS OR RESULTS TO DIFFER MATERIALLY FROM THOSE EXPRESSED BY THE FORWARD-LOOKING STATEMENTS. -

Indicators of Success and Challenges in Northern Virginia Northern Virginia Is a Diverse, Growing Region with a Well-Educated Population and Strong Economy

Indicators of Success and Challenges in Northern Virginia Northern Virginia is a diverse, growing region with a well-educated population and strong economy. However, with this success comes challenges such as high CONTENTS housing costs and long commutes that hit low-income residents particularly hard. 1 about the opportunity index The region--Arlington County, Alexandria City, Falls Church City, Fairfax County, 2 general demographics Fairfax City, Loudoun County, Manassas City, Manassas Park City, and Prince William 11 economy County--also continues to be heavily dependent on federal employment, both 19 education directly and through federal contracts. And despite some success in narrowing 25 community health & civic life educational achievement gaps, Black and Hispanic/Latino residents of the region 36 moving forward continue to have higher unemployment and poverty rates, lower household incomes, and lower rates of health insurance access than their non-Hispanic White and Asian peers in the region. In conjunction with the Community ABOUT THE COMMUNITY FOUNDATION FOR Foundation’s 40th Anniversary, it NORTHERN VIRGINIA commissioned this report from The Commonwealth Institute to gain some The Community Foundation for Northern Virginia is a visionary perspective on changes and growth in funder that has directed millions of charitable dollars to our region over the past 40 years, and people in need since 1978. Its mission is to grow philanthropy to provide insight into current trends to respond to critical need and seed innovation in our region. that will help guide its future work to Serving all of Northern Virginia, including Arlington, Fairfax, make the greatest impact in responding Loudoun and Prince William Counties and the cities of to critical need and seeding innovation. -

Resolution #20-9

BALTIMORE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION BALTIMORE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION BOARD RESOLUTION #20-9 RESOLUTION TO ENDORSE THE UPDATED BALTIMORE REGION COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT – HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board (BRTB) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region, encompassing the Baltimore Urbanized Area, and includes official representatives of the cities of Annapolis and Baltimore; the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s; and representatives of the Maryland Departments of Transportation, the Environment, Planning, the Maryland Transit Administration, Harford Transit; and WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Baltimore region, has responsibility under the provisions of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act for developing and carrying out a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive transportation planning process for the metropolitan area; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration, a modal division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, requires under FAST Act the establishment of a locally developed, coordinated public transit-human services transportation plan. Previously, under MAP-21, legislation combined the New Freedom Program and the Elderly Individuals and Individuals with Disabilities Program into a new Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program, better known as Section 5310. Guidance on the new program was provided in Federal Transit Administration Circular 9070.1G released on June 6, 2014; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration requires a plan to be developed and periodically updated by a process that includes representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and participation by the public. -

Multifamily Rental Market Assessment

RealPropertyResearchGroup Multifamily Rental Market Assessment Frederick County, Maryland Date: April 2010 Prepared for: Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development Community Development Administration BRAC Market Study Services Contract 10400 LITTLE PATUXENT PARKWAY SUITE 450 VOICE 410.772.1004 COLUMBIA, MARYLAND 21044 FAX 410.772.1110 RealPropertyResearchGroup April 16, 2010 Ms. Patricia Rynn Sylvester Director, Multifamily Housing Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development 100 Community Place Crownsville, Maryland 21032-2023 and Ms. Jenny Short Director Frederick County Department of Housing and Community Development 520 North Market Street Frederick, Maryland 21701 RE: Frederick County Multifamily Rental Market Assessment Dear Ms. Sylvester and Ms. Short: We are pleased to present our comprehensive assessment of the Multifamily Rental Market in Frederick County, Maryland. This is the first of two deliverables under our contract with the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development (the “Department”). The second deliverable will be an electronic database of the inventory of multifamily rental properties in Frederick County with a ranking of the properties in order of feasibility for preservation as affordable housing. This assignment is part of the Maryland Preservation Compact, a partnership between the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, MD-DHCD and the eight subject Maryland counties: Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Cecil, Frederick, Harford, Howard, Prince George’s and St. Mary’s Counties. The Compact seeks to preserve the existing stock of affordable rental housing in Maryland in areas anticipated to be impacted by growth stemming from the US Department of Defense’s ongoing efforts to expand military installations throughout the state. Maryland stands to gain more military, civilian and mission contractor personnel than any other state under the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) recommendations approved by the President and Congress in 2005. -

5 Planned Transit Service Improvements

Metro Transit Central-South (Sector 5) Final Plan 4.5 Public Outreach Conclusions Stakeholder and public comments provided guidance to improve various elements of the plan. About one fifth of the comments favored the plan. Four cities, one county and the University of Minnesota also supported the plan. Several neighborhood groups expressed concerns about specific elements of the plan. The majority of comments (over 60 percent) were in response to the proposed route elimination or service reductions on Routes 7, 8, 18, 19, 22, 52B, 84, 538 and 539. Another frequent comment was concern regarding increased transfers and loss of direct service to key destinations. For example, the proposed elimination of some direct service to the University of Minnesota was the source of many complaints. The Concept Plan was modified to address many of the stakeholder and customer concerns within the current operating budget and the tenants identified in the previous chapters. Of the 55 routes in the sector, 32 or 58 percent of routes were modified in response to public comment. The final plan preserves geographic coverage in all of the urban area, and most of the suburban areas, and direct service to the University of Minnesota from France Avenue/ W. 50th Street, Cedar Avenue/Portland Avenue and Snelling Avenue. This final plan, as modified to address the concerns raised during the public outreach phase, is supported by all five cities and the two counties found in the study area. 5 Planned Transit Service Improvements 5.1 Planned Transit Service Network The service improvement program begins with a high-to-medium frequency grid network of local service in high-density population and employment areas such as south Minneapolis and St. -

Viennaviennaandand Oaktonoakton Tysons Welcomes Metrorail News, Page 3

ViennaViennaandand OaktonOakton Tysons Welcomes Metrorail News, Page 3 Classifieds, Page 14 Classifieds, ❖ Sports, Page 12 ❖ Entertainment, Page 10 ❖ Opinion, Page 6 A Silver Line metro train pulls into the Tysons Corner Sta- ‘They’re Thinking tion carrying passen- gers for the very first time on Satur- Beyond Themselves’ day, July 26. News, Page 16 Vienna Youth Players Present Musical Entertainment, Page 8 Photo by Ryan Dunn/ The Connection www.ConnectionNewspapers.comJuly 30 - August 5, 2014 onlineVienna/Oakton at www.connectionnewspapers.com Connection ❖ July 30 - August 5, 2014 ❖ 1 2 ❖ Vienna/Oakton Connection ❖ July 30 - August 5, 2014 www.ConnectionNewspapers.com News Photos by Photos Reena Singh / The Connection People rushing to get on the first public Silver Line rail cars on Saturday, Local, state and national officials at the ribbon-cutting ceremony for the July 26, at Weihle-Reston East Silver Line station. Silver Line on Saturday. Weihle-Reston East to Silver Line Officially Opens Largo Town Center. By Reena Singh some vocally - disappointed. “Welcome aboard the Silver Line!” said She and other officials, including Gov. The Connection After years of promises, history was be- Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Au- Terry McAuliffe and U.S. Secretary of Trans- ing made. Local residents wanted to be a thority CEO Richard Sarles. “It’s time to portation Anthony Foxx, rode the very first fter the speeches, after the rib- part of it. ride.” rail cars to the W-RE station before the cer- bon-cutting, there was a mad WMATA expects 37 percent of current rail emony. Arush to board the first publicly THE SILVER LINE grand opening cer- riders will experience shorter wait times “I just rode the car from Tysons,” said Gov. -

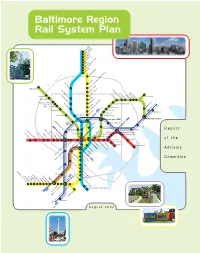

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report

Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Report of the Advisory Committee August 2002 Advisory Committee Imagine the possibilities. In September 2001, Maryland Department of Transportation Secretary John D. Porcari appointed 23 a system of fast, convenient and elected, civic, business, transit and community leaders from throughout the Baltimore region to reliable rail lines running throughout serve on The Baltimore Region Rail System Plan Advisory Committee. He asked them to recommend the region, connecting all of life's a Regional Rail System long-term plan and to identify priority projects to begin the Plan's implemen- important activities. tation. This report summarizes the Advisory Committee's work. Imagine being able to go just about everywhere you really need to go…on the train. 21 colleges, 18 hospitals, Co-Chairs 16 museums, 13 malls, 8 theatres, 8 parks, 2 stadiums, and one fabulous Inner Harbor. You name it, you can get there. Fast. Just imagine the possibilities of Red, Mr. John A. Agro, Jr. Ms. Anne S. Perkins Green, Blue, Yellow, Purple, and Orange – six lines, 109 Senior Vice President Former Member We can get there. Together. miles, 122 stations. One great transit system. EarthTech, Inc. Maryland House of Delegates Building a system of rail lines for the Baltimore region will be a challenge; no doubt about it. But look at Members Atlanta, Boston, and just down the parkway in Washington, D.C. They did it. So can we. Mr. Mark Behm The Honorable Mr. Joseph H. Necker, Jr., P.E. Vice President for Finance & Dean L. Johnson Vice President and Director of It won't happen overnight. -

Part 1: Downtown Transit Center and Circulator Shuttle

Howard Research and Development Corporation Downtown Columbia Downtown Transit Center and Circulator Shuttle Feasibility Study: Part 1 - Downtown Transit Center & Downtown Circulator Shuttle (Part of CEPPA #5) DRAFTDecember 2011 Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................. iv Chapter 1. Downtown Columbia Transit Center ....................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 2. Downtown Columbia Circulator Shuttle ............................................................................................... 12 Appendix A. Regional Transit System Evaluation .............................................................................................. 21 Appendix B. Regional Transit Market Analysis .................................................................................................. 46 Appendix C. Transit Circulator Design ................................................................................................................ 64 Appendix D. Transit Center Site Evaluation ...................................................................................................... 764 Appendix E. Transit Development Plan ............................................................................................................... 79 DRAFT Page i• Nelson\Nygaard Consulting Associates Inc. Table of Figures Figure 1 Existing -

The Bulletin STATEN ISLAND’S 157-YEAR-OLD RAILROAD

ERA BULLETIN — SEPTEMBER, 2017 The Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 60, No. 9 September, 2017 The Bulletin STATEN ISLAND’S 157-YEAR-OLD RAILROAD Published by the Electric (Continued from August, 2017 issue) Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box Before the end of 1925, the railroad was Buses adjacent to the railroad appeared in 3323, New York, New able to operate full electric service from St. the 1920s, but the railroad still made a profit. York 10163-3323. George to Tottenville, South Beach, and Ar- Several years later, railroad riding declined lington with 100 new M.U. electric cars. The because of competition from the buses. For general inquiries, or fleet was composed of 90 motor cars num- When the Isle Transportation Company sur- Bulletin submissions, bered 300-389 and ten trailers numbered rendered its franchise on February 23, 1947, contact us at bulletin@ erausa.org. ERA’s 500-509, of which five were eventually con- the Board of Transportation started operating website is verted to motors. Freight was also carried on the buses immediately, retaining the five-cent www.erausa.org. nearly the entire line, including the non- fare with several five-cent zones depending electrified track extending from Arlington on the distance. On July 1, 1948, bus fares Editorial Staff: across the bridge to Cranford Junction, New were increased to seven cents, zone fares Editor-in-Chief: Bernard Linder Jersey. Because the passenger service usu- were abolished, and passengers could buy a Tri-State News and ally operated at a deficit, the company was 2-cent transfer valid on subway lines at Commuter Rail Editor: unable to spend $17 million to extend the South Ferry, Manhattan. -

Howard County Transportation

Howard County Transportation September MTB Meeting September 29, 2020 Today’s Agenda 1) Approval of Agenda for Meeting – Chairperson Schoen 2) Approval of AUGUST 25, 2020 Meeting Minutes – Chairperson Schoen 3) Public Comment – General Topics (Participants that have signed up in advance will have 3 minutes each to address the MTB) 4) Follow up on Roadway Safety Plan Comments (verbal) – David Cookson & Cindy Burch Chris Eatough 5) Approval No presentation will be provided. For review of Complete of materials please see: Streets https://www.howardcountymd.gov/Depart Engagement ments/County- Plan – Administration/Transportation/Complete- Streets/Community-Engagement Bruce Gartner MDOT CTP Statewide book – includes overview 6) MDOT CTP and capital program for all business units with the Overview and exception of MDOT-SHA County capital programs. MTA Service Link for document: Reductions http://www.mdot.maryland.gov/newMDOT/Plann ing/CTP/CTP_21_26/Draft_Documents/Entire%20 FY%2021-26%20CTP.pdf Long Term State Funding Decisions Negatively Impact Baltimore Region • Significant Transit Reductions in Baltimore Region versus limited impact to Central MD Transit Plan Washington Suburbs creates a concern about regional equity. • How will the Purple Line legal and contracting problems impact Baltimore Region? • What Can MDOT and Governor Hogan do to reallocate existing state or future federal funds to scale back some of the transit reductions being proposed in this CTP? MDOT Consolidated Transportation Program Reductions MDOT’s draft 6-year Consolidated Transportation Program (CTP) for FY2021-2026. shows a $2.9 billion reduction over the last 6-year plan • While the cuts are distributed across MDOT modes, Maryland’s contribution to WMATA is 100% funded for capital and operating (as of 9-25-20) • $150 million in cuts to MTA on top of last year’s $303 million reduction to the 6-year CTP will further impact the failing transit network in the Baltimore region • Cuts to system preservation budgets for all MDOT modes has a longer term fiscal impact on our transportation network. -

Washington Metropolitan Region Transportation Demand

Item #3 [Type text] Page 1 FY15 Washington Reg. TDM Resource Guide & Strategic Mktg Plan Final Report 12-16-14 Page 2 FY15 Washington Reg. TDM Resource Guide & Strategic Mktg Plan Final Report 12-16-14 Page 3 BACKGROUND The Washington metropolitan region initiated its first formal transportation demand management efforts in the early 1970s with Commuter Club, which was established by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (COG), the General Services Administration, and the Greater Washington Board of Trade to provide basic ridematching for carpools and vanpools. In subsequent years, the program grew into a COG-coordinated network of local rideshare agencies, and in 1989, it became the Ride Finders Network which provided free information and computerized ride matching services to area residents seeking to join car or vanpools or locate appropriate transit arrangements and park-and-ride locations. In 1996, the regional network was renamed Commuter Connections. In 1997, Commuter Connections expanded its services to include regional telework assistance and resources, its first website, a regional Guaranteed Ride Home program, information on bicycling to work, InfoExpress commuter information kiosks, and free assistance to employers for the development and implementation of alternative commute programs and benefits. In 1998 Commuter Connections began to honor employers in the region through the Employer Recognition Awards program. In 2000, Commuter Connections rolled out Bike to Work Day as a regional entity, initially started as a DC based event by the Washington Area Bicyclist Association. In 2003, Commuter Connections expanded its marketing efforts through the implementation of a regional mass marketing measure. The purpose of the measure was to brand the Commuter Connections name as the umbrella organization for commuter transportation information in the Washington Metropolitan area and to subsequently increase the use of alternative forms of commuting.