Lord Holland's Portuguese Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poems About Poets

1 BYRON’S POEMS ABOUT POETS Some of the funniest of Byron’s poems spring with seeming spontaneity from his pen in the middle of his letters. Much of this section comes from correspondence, though there is some formal verse. Several pieces are parodies, some one-off squibs, some full-length. Byron’s distaste for most of the poets of his day shines through, with the recurrent and well-worn traditional joke that their books will end either as stuffing in hatshops, wrapped around pastries, or as toilet-tissue. Byron admired the English poets of the past – the Augustans especially – much more than he did any of his contemporaries. Of “the Romantic Movement” he knew no more than did any of the other writers supposed now to have been members of it. Southey he loathed, as a dreadful doppelgänger – see below. Of Wordsworth he also had a low opinion, based largely on The Excursion – to the ambitions of which Don Juan can be regarded as a riposte (there are as many negative comments about Wordsworth in Don Juan as there are about Southey). He was as abusive of Keats as it’s possible to be, and only relented (as he said), when Shelley showed him Hyperion. Of the poetry of his friend Shelley he was very guarded indeed, and compensated by defending Shelley’s moral reputation. Blake he seems not to have known (“Blake” was him the name of a well-known Fleet Street barber). The only poet of whom his judgement and modern estimate coincide is Coleridge: he was strong in his admiration for The Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan, and Christabel; about the conversational poems he seems blank, and he feigns total incomprehension of the Biographia Literaria (see below). -

Product Manual

PRODUCT MANUAL The Sami of Finnmark. Photo: Terje Rakke/Nordic Life/visitnorway.com. Norwegian Travel Workshop 2014 Alta, 31 March-3 April Sorrisniva Igloo Hotel, Alta. Photo: Terje Rakke/Nordic Life AS/visitnorway.com INDEX - NORWEGIAN SUPPLIERS Stand Page ACTIVITY COMPANIES ARCTIC GUIDE SERVICE AS 40 9 ARCTIC WHALE TOURS 57 10 BARENTS-SAFARI - H.HATLE AS 21 14 NEW! DESTINASJON 71° NORD AS 13 34 FLÅM GUIDESERVICE AS - FJORDSAFARI 200 65 NEW! GAPAHUKEN DRIFT AS 23 70 GEIRANGER FJORDSERVICE AS 239 73 NEW! GLØD EXPLORER AS 7 75 NEW! HOLMEN HUSKY 8 87 JOSTEDALSBREEN & STRYN ADVENTURE 205-206 98 KIRKENES SNOWHOTEL AS 19-20 101 NEW! KONGSHUS JAKT OG FISKECAMP 11 104 LYNGSFJORD ADVENTURE 39 112 NORTHERN LIGHTS HUSKY 6 128 PASVIKTURIST AS 22 136 NEW! PÆSKATUN 4 138 SCAN ADVENTURE 38 149 NEW! SEIL NORGE AS (SAILNORWAY LTD.) 95 152 NEW! SEILAND HOUSE 5 153 SKISTAR NORGE 150 156 SORRISNIVA AS 9-10 160 NEW! STRANDA SKI RESORT 244 168 TROMSØ LAPLAND 73 177 NEW! TROMSØ SAFARI AS 48 178 TROMSØ VILLMARKSSENTER AS 75 179 TRYSILGUIDENE AS 152 180 TURGLEDER AS / ENGHOLM HUSKY 12 183 TYSFJORD TURISTSENTER AS 96 184 WHALESAFARI LTD 54 209 WILD NORWAY 161 211 ATTRACTIONS NEW! ALTA MUSEUM - WORLD HERITAGE ROCK ART 2 5 NEW! ATLANTERHAVSPARKEN 266 11 DALSNIBBA VIEWPOINT 1,500 M.A.S.L 240 32 DESTINATION BRIKSDAL 210 39 FLØIBANEN AS 224 64 FLÅMSBANA - THE FLÅM RAILWAY 229-230 67 HARDANGERVIDDA NATURE CENTRE EIDFJORD 212 82 I Stand Page HURTIGRUTEN 27-28 96 LOFOTR VIKING MUSEUM 64 110 MAIHAUGEN/NORWEGIAN OLYMPIC MUSEUM 190 113 NATIONAL PILGRIM CENTRE 163 120 NEW! NORDKAPPHALLEN 15 123 NORWEGIAN FJORD CENTRE 242 126 NEW! NORSK FOLKEMUSEUM 140 127 NORWEGIAN GLACIER MUSEUM 204 131 STIFTELSEN ALNES FYR 265 164 CARRIERS ACP RAIL INTERNATIONAL 251 2 ARCTIC BUSS LOFOTEN 56 8 AVIS RENT A CAR 103 13 BUSSRING AS 47 24 COLOR LINE 107-108 28 COMINOR AS 29 29 FJORD LINE AS 263-264 59 FJORD1 AS 262 62 NEW! H.M. -

John Hookham Frere 1769-1846

JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE 1769-1846 Ta' A. CREMONA FOST il-Meċenti tal-Lsien Malti nistgħu ngħoddu lil JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE li barra mill-imħabba li kellu għall-ilsna barranin, Grieg, Latin, Spanjol, li scudjahom u kien jafhom tajjeb, kien wera ħrara u ħeġġa kbira biex imexxi '1 quddiem l-istudju tal-Malti, kif ukoll tal-ilsna orjentali, fosthom il-Lhudi u l-Għarbi, ma' tul iż-żmien li kien hawn Malta u baqa' hawnhekk sa mewtu. JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE twieled Londra fil-21 ta' Mejju, 1769. FI-1785 beda l-istudji tiegħu fil-Kulleġġ ta' Eton. Niesu mhux dejjem kienu jo qogtldu b'darhom Londra, iżda dlonk ma' tul is-sena kienu jmorru jgħixu ukoll Roydon f'Norfolk u f'Redington f'Surrey. F'Eton, fejn studja l-lette ratura Ingliża, Griega u Latina, kien sar ħabib tal-qalb ta' George Canning li l-ħbiberija tagħhom baqgħet għal għomorhom. Fl-1786, flimkien ma' xi studenti tal-Kulleġġ [la sehem fil-pubblikazzjoni tar-u vista Microcosm li bil-kitba letterar;a li kien fiha kienet ħadet isem fost l-istudenti ta' barra -il-kulleġġ. Minn Eton, Hookham Frere kien daħal f'Caius College, f'Cam bridge, fejn ħa l-grad tal-Baċellerat tal-Arti 8-1792 u l-Magister Artium fl-1795, u kiseb ie-titlu ta' Fellow of Caius għall-kitba tiegħu klassika ta' proża u versi. Fl-1797 issieħeb ma' Canning u xi żgħażagħ oħra fil-pub blikazzjoni tal-ġumal Anti-] acobin li kien joħroġ kull ġimgħa, nhar ta' Tnejn, bil-ħsieb li jrażżan il-propaganda tal-Partit Republikan Franċiż li kien qed ihedded il-monarkija tal-Istati Ewropej bil-filosofija Ġakbina tiegħu. -

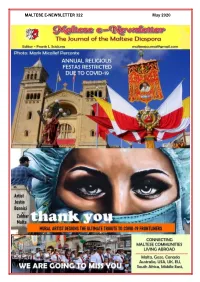

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 French Occupation of Malta Malta and all of its resources over to the French in exchange for estates and pensions in France for himself and his knights. Bonaparte then established a French garrison on the islands, leaving 4,000 men under Vaubois while he and the rest of the expeditionary force sailed eastwards for Alexandria on 19 June. REFORMS During Napoleon's short stay in Malta, he stayed in Palazzo Parisio in Valletta (currently used as the Ministry for Foreign Affairs). He implemented a number of reforms which were The French occupation of The Grandmaster Ferdinand von based on the principles of the Malta lasted from 1798 to 1800. It Hompesch zu Bolheim, refused French Revolution. These reforms was established when the Order Bonaparte's demand that his could be divided into four main of Saint John surrendered entire convoy be allowed to enter categories: to Napoleon Bonaparte following Valletta and take on supplies, the French landing in June 1798. insisting that Malta's neutrality SOCIAL meant that only two ships could The people of Malta were granted FRENCH INVASION OF MALTA enter at a time. equality before the law, and they On 19 May 1798, a French fleet On receiving this reply, Bonaparte were regarded as French citizens. sailed from Toulon, escorting an immediately ordered his fleet to The Maltese nobility was expeditionary force of over bombard Valletta and, on 11 June, abolished, and slaves were freed. 30,000 men under General Louis Baraguey Freedom of speech and the press General Napoleon Bonaparte. -

The Virginia Gazette : Genealogy

5o4s~. ,_Friday, January 14,, 1955 THE VIRGINIA GAZETTE, WILLIAMSBU Sarah ................ (b. ........, d. aft. 1684) & had, (7) John Billups ‘GENEALOGY (1660-aft. 1709) m.- bef. June 6, 1695 to Mary Gasscock & had (6) By Hugh 3. Watson Joseph Billups (1697-1767), m. 17l9, Margaret Lilly (1700-1770). WATSONIAN OBSERVATION orded in Petersburg, Va. Joanna & had (5) Robert Bil-.lups (Mar. OF THE WEEK: In our research Ellis is one of the witnesses with 1720- d. bef. 1795) m.- June 14, 1755 to Ann Ransone (b. ........, d. we find many unusual names and Wm Davis & Cyrus Ferguson to often wonder where they derived: ........), & had (4) John Billups (b. this will, naming the wife as Polly among some I have come across lvlar. 17, 1755-6, cl. Oct. 23. 1814) recently was the surname of & “my mother Letty Skipwith.” m.- 1798 to Susannah (Carleton) BIBLE; another was that of a This would show that the wife of Cox (b. 5-6-1761, d. 1-10-1817), gentleman by the name of “Wil Augustine Ellis may have been & had (3) Col. Thomas Carleton liam Crank Ford.” Perhaps some the Mary Skipwith. In the lineage Billups (b. 4-2-1804, d. 1866) m. 9-13-1847 to Frances Ann Saun of my readers have found some book of “National Society of just as unusual. Daughters of Founders & Pa ders (13.4-12-1808, (1. 6-1-1890), & triots,” Vo1.'XV, pp. 79-80 is had (2) James Saunders Billups QUERIES found the lineage of Mrs. John M. (b. 11-22-1808, d. 1-11-1919), m.-. -

Byron's Library

1 BYRON’S LIBRARY: THE THREE BOOK SALE CATALOGUES Edited and introduced by Peter Cochran The 1813 Catalogue Throughout much of 1813, Byron was planning to go east again, not with Hobhouse this time, but with the Marquis of Sligo, who, just out of jail for abducting sailors during a period of war, was anxious to be away from the public gaze. They never went: the difficulty of finding adequate transport for themselves and their retinues, plus a report of plague in the Levant, prevented them. Sligo would have had difficulty in any case getting passage on an English ship of war. However, just how close they got to leaving is shown by the first of the three catalogues below. While still adding lines to The Giaour, Byron was within an ace of selling his library. Its catalogue is headed: A / CATALOGUE OF BOOKS, / THE PROPERTY OF A NOBLEMAN [in ink in margin: Lord Byron / J.M.] / ABOUT TO LEAVE ENGLAND / ON A TOUR OF THE MOREA. / TO WHICH ARE ADDED / A SILVER SEPULCHRAL URN, / CONTAINING / RELICS BROUGHT FROM ATHENS IN 1811, / AND / A SILVER CUP, / THE PROPERTY OF THE SAME NOBLE PERSON; / WHICH WILL BE / SOLD BY AUCTION / BY R. H. EVANS / AT HIS HOUSE, No. 26, PALL-MALL, / On Thursday July 8th, and following Day. Catalogues may be had, and the Books viewed at the / Place of Sale. / Printed by W.Bulmer and Co. Cleveland-row, St. James’ s. / 1813. It’s not usual to sell your entire library before going abroad unless you intend never to return. -

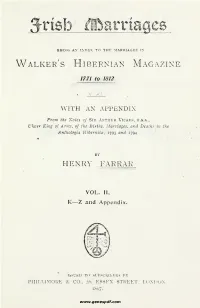

Irish Marriages, Being an Index to the Marriages in Walker's Hibernian

— .3-rfeb Marriages _ BBING AN' INDEX TO THE MARRIAGES IN Walker's Hibernian Magazine 1771 to 1812 WITH AN APPENDIX From the Notes cf Sir Arthur Vicars, f.s.a., Ulster King of Arms, of the Births, Marriages, and Deaths in the Anthologia Hibernica, 1793 and 1794 HENRY FARRAR VOL. II, K 7, and Appendix. ISSUED TO SUBSCRIBERS BY PHILLIMORE & CO., 36, ESSEX STREET, LONDON, [897. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1729519 3nK* ^ 3 n0# (Tfiarriages 177.1—1812. www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com Seventy-five Copies only of this work printed, of u Inch this No. liS O&CLA^CV www.genespdf.com www.genespdf.com 1 INDEX TO THE IRISH MARRIAGES Walker's Hibernian Magazine, 1 771 —-1812. Kane, Lt.-col., Waterford Militia = Morgan, Miss, s. of Col., of Bircligrove, Glamorganshire Dec. 181 636 ,, Clair, Jiggmont, co.Cavan = Scott, Mrs., r. of Capt., d. of Mr, Sampson, of co. Fermanagh Aug. 17S5 448 ,, Mary = McKee, Francis 1S04 192 ,, Lt.-col. Nathan, late of 14th Foot = Nesbit, Miss, s. of Matt., of Derrycarr, co. Leitrim Dec. 1802 764 Kathcrens, Miss=He\vison, Henry 1772 112 Kavanagh, Miss = Archbold, Jas. 17S2 504 „ Miss = Cloney, Mr. 1772 336 ,, Catherine = Lannegan, Jas. 1777 704 ,, Catherine = Kavanagh, Edm. 1782 16S ,, Edmund, BalIincolon = Kavanagh, Cath., both of co. Carlow Alar. 1782 168 ,, Patrick = Nowlan, Miss May 1791 480 ,, Rhd., Mountjoy Sq. = Archbold, Miss, Usher's Quay Jan. 1S05 62 Kavenagh, Miss = Kavena"gh, Arthur 17S6 616 ,, Arthur, Coolnamarra, co. Carlow = Kavenagh, Miss, d. of Felix Nov. 17S6 616 Kaye, John Lyster, of Grange = Grey, Lady Amelia, y. -

Skipsforlis 1906 1) Jernbark AILSA (HFTW) Bygd Av Barclay Curle & Co., Glasgow (# 163) 1212 Brt, 1145 Nrt 227.7 X 34.8 X 22

Skipsforlis 1906 1) Jernbark AILSA (HFTW) Bygd av Barclay Curle & Co., Glasgow (# 163) 1212 brt, 1145 nrt 227.7 x 34.8 x 22.7 1867: Juli: Levert som CITY OF DELHI for George Smith & Sons, Glasgow, UK Var opprinnelig fullrigger 1900: Mars: Solgt til J. Johanson & Co., Lysaker/Kristiania. Rigget ned til bark Omdøpt AILSA . 1906: 02.01.: Forlatt på 56.51 N, 12.35 V, på reise Ardrossan – Rio de Janeiro med kull. 2) Bark CARL PIHL (JLNW) Bygd av C. Haasted, Aalesund 747 brt, 672 nrt 170.6 x 33.9 x 19.1 1875: Levert som CARL PIHL for Eid av Ths. S. Falck, Stavanger 1906: 05.01.: Ankom Queenstown lekk på reise Newport Mon. - Pernambuco med kull. Kondemnert og rigget ned til lekter. 3) Bark CORDILLERA (JBDR) Bygd av L. Hewitt, La Have NS, Canada 694 brt, 635 nrt 158.0 x 34.6 x 17.9 1874: Levert som SCOTIA for Jas. H. Smeltzer, Lunenburg NS, Canada 1893: Solgt til R. Dawson & Sons, Lunenburg NS, Canada 1897: Solgt til C. P. Erford, Buenos Aires, Arg. Omdøpt STELLA ERFORD 1900: Solgt til Juel & Westerby, La Plata, Arg. Omdøpt CORDILLERA 1901: Solgt til A. Boe Amundsen, Grimstad 1904: Solgt til A/S Cordillera (Aug. Olsen), Kristiania 1906: 05.01.: Forlatt og stukket i brann på 33.41 N, 41.56 V, på reise St.John NB – Buenos Aires med trelast. 4) Fullrigger SERVIA (KBPF) Bygd av A. Loomer, Parrsboro’ NS, Canada 1314 brt, 1227 nrt 197.0 x 40.0 x 23.4 1878: Levert som SERVIA for Thomas E. -

History of the Clan Macfarlane

HISTORY OF THE CLAN MACFARLAN Mrs. C. M. Little [gc M. L 929.2 M164t GENEALOGY COLLECTION I I 1149534 \ ALLEN CCnjmVPUBUCUBBABY, 334Z 3 1833 00859 Hf/^. I /^^^^^^ IIISTOKV OF TH1-: CLAN MACFARLANE, (.Macfai'lane) MACFARLAN. MACFARLAND, MACFARLIN. BY MRS. C. M. TJTTLE. TOTTENVILLE, N. Y. MRS. C. M. LITTLK. 1893. Copyrighted. Mrs. C. M. LITTLK 1893. For Private Circucation. 1149534 TO MY DEAR AND AGED MOTHER, WHO, IN HER NINETIETH YEAR, THE LAST OF HER GENERA- TION, WITH INTELLECT UNIMPAIRED, STANDS AS A WORTHY REPRESENTATIVE OF THE INDOM- ITABLE RACE OF MACFARLANE, THIS BOOK IS REVERENTLY deDicatgD, BY HER AFFECTIONATE DAUGHTER, THE AUTHOR. — INTRODUCTION. " Why dost thou build the hall? Son of the winged days! Thou lookest from thy tower to-day; yet a few years and the blast of the desert comes: it howls in thy empty court." Ossian. Being, myself, a direct descendant of the Clan MacFarlane, the old "Coat of Arms" hanging up- on the wall one of my earliest recollections, the oft-repeated story of the great bravery at Lang- side that gave them the crest, the many tradi- tions told by those who have long since passed away, left npon my mind an impression so indeli- ble, that, as years rolled on, and I had become an ardent student of Scottish history, I determined to know more of my ancestors than could be gathered from oral traditions. At length, in the summer of 1891, traveling for the second time in Europe, I was enabled to exe- cute a long-cherished plan of spending some time at Arrochar, at the head of Loch Long, in the Highlandsof Scotland, the hereditary posses- sions for six hundred years of the chiefs of the Clan MacFarlane. -

Don Juan Study Guide

Don Juan Study Guide © 2017 eNotes.com, Inc. or its Licensors. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. Summary Don Juan is a unique approach to the already popular legend of the philandering womanizer immortalized in literary and operatic works. Byron’s Don Juan, the name comically anglicized to rhyme with “new one” and “true one,” is a passive character, in many ways a victim of predatory women, and more of a picaresque hero in his unwitting roguishness. Not only is he not the seductive, ruthless Don Juan of legend, he is also not a Byronic hero. That role falls more to the narrator of the comic epic, the two characters being more clearly distinguished than in Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. In Beppo: A Venetian Story, Byron discovered the appropriateness of ottava rima to his own particular style and literary needs. This Italian stanzaic form had been exploited in the burlesque tales of Luigi Pulci, Francesco Berni, and Giovanni Battista Casti, but it was John Hookham Frere’s (1817-1818) that revealed to Byron the seriocomic potential for this flexible form in the satirical piece he was planning. The colloquial, conversational style of ottava rima worked well with both the narrative line of Byron’s mock epic and the serious digressions in which Byron rails against tyranny, hypocrisy, cant, sexual repression, and literary mercenaries. -

May 7, 2000 Hometownnewspapers

lomeTOwn COMMUNICATIONS N B T W O ft K Wcstlano <8)b0mrer Your hometown newspaper serving Westland for 35 years Sunday, May 7, 2000 hometownnewspapers. net 75c Volume 35 Number 97 Westland, Michigan 00000 Hometown Communications Network™ THE WEEK AHEAD MONDAY Council business: West- land City Council study sessions on the city bud get will begin 5:30p.m. May 8 at City Hall, on Ford near Carlson. An 8:30 p.m. session on the clerk consultant contract is planned. Budget ses sions continue May 10 and May 17. School board: The Wayne- Westland Board of Edu Pray with me: Clasped hands cation will meet 7p.m. express the deep emotion that May 8at the board office, was prevalent among wor on Marquette between , STAJT PBOTt* BY KvrTWtV TArtJNCtK shippers who gathered Newburgh and Wayne Praise God: Susan May, a former drug addict who found religion after failed rehab attempts, Thursday afternoon in front roads in Westland. spreads her arms wide during an emotional moment in prayer at Westland City Hall, of City Hall. TUESDAY Mayor speaks: Westland Prayer prompts calm protest Mayor Robert Thomas will speak to the Westland National Day of Prayer at Westland City Hall Views: included a group of atheists this year. Mem Henry Mor Chamber of Commerce. bers of American Athei sts Inc. oppose the gan, Michi The business luncheon use ofjzovernment property to endorse reli gan state begins 11:30 a.m. May 9 gion. The protest was peaceful. director of at Joy Manor, on Joy east BY KURT KUBAN of .government and religion,- came to the Ameri of Middlebelt in West- STAFF WRITER protest the event, at which partici can Athe land. -

Catalogue of Place Names in Northern East Greenland

Catalogue of place names in northern East Greenland In this section all officially approved, and many Greenlandic names are spelt according to the unapproved, names are listed, together with explana- modern Greenland orthography (spelling reform tions where known. Approved names are listed in 1973), with cross-references from the old-style normal type or bold type, whereas unapproved spelling still to be found on many published maps. names are always given in italics. Names of ships are Prospectors place names used only in confidential given in small CAPITALS. Individual name entries are company reports are not found in this volume. In listed in Danish alphabetical order, such that names general, only selected unapproved names introduced beginning with the Danish letters Æ, Ø and Å come by scientific or climbing expeditions are included. after Z. This means that Danish names beginning Incomplete documentation of climbing activities with Å or Aa (e.g. Aage Bertelsen Gletscher, Aage de by expeditions claiming ‘first ascents’ on Milne Land Lemos Dal, Åkerblom Ø, Ålborg Fjord etc) are found and in nunatak regions such as Dronning Louise towards the end of this catalogue. Å replaced aa in Land, has led to a decision to exclude them. Many Danish spelling for most purposes in 1948, but aa is recent expeditions to Dronning Louise Land, and commonly retained in personal names, and is option- other nunatak areas, have gained access to their al in some Danish town names (e.g. Ålborg or Aalborg region of interest using Twin Otter aircraft, such that are both correct). However, Greenlandic names be - the remaining ‘climb’ to the summits of some peaks ginning with aa following the spelling reform dating may be as little as a few hundred metres; this raises from 1973 (a long vowel sound rather than short) are the question of what constitutes an ‘ascent’? treated as two consecutive ‘a’s.