Aristophanes in Performance 421 BC–AD 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert's Mature Operas: an Analytical Study

Durham E-Theses Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study Bruce, Richard Douglas How to cite: Bruce, Richard Douglas (2003) Schubert's mature operas: an analytical study, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4050/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Richard Douglas Bruce Submitted for the Degree of PhD October 2003 University of Durham Department of Music A copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without their prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. 2 3 JUN 2004 Richard Bruce - Schubert's Mature Operas: An Analytical Study Submitted for the degree of Ph.D (2003) (Abstract) This thesis examines four of Franz Schubert's complete operas: Die Zwillingsbruder D.647, Alfonso und Estrella D.732, Die Verschworenen D.787, and Fierrabras D.796. -

Marginalia and Commentaries in the Papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes

Nikolaos Athanassiou Marginalia and Commentaries in the Papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes PhD thesis / Dept. of Greek and Latin University College London London 1999 C Name of candidate: Nikolaos Athanassiou Title of Thesis: Marginalia and commentaries in the papyri of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes. The purpose of the thesis is to examine a selection of papyri from the large corpus of Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes. The study of the texts has been divided into three major chapters where each one of the selected papyri is first reproduced and then discussed. The transcription follows the original publication whereas any possible textual improvement is included in the commentary. The commentary also contains a general description of the papyrus (date, layout and content) as well reference to special characteristics. The structure of the commentary is not identical for marginalia and hy-pomnemata: the former are examined in relation to their position round the main text and are treated both as individual notes and as a group conveying the annotator's aims. The latter are examined lemma by lemma with more emphasis upon their origins and later appearances in scholia and lexica. After the study of the papyri follows an essay which summarizes the results and tries to incorporate them into the wider context of the history of the text of each author and the scholarly attention that this received by the Alexandrian scholars or later grammarians. The main effort is to place each papyrus into one of the various stages that scholarly exegesis passed especially in late antiquity. Special treatment has been given to P.Wurzburg 1, the importance of which made it necessary that it occupies a chapter by itself. -

Poems About Poets

1 BYRON’S POEMS ABOUT POETS Some of the funniest of Byron’s poems spring with seeming spontaneity from his pen in the middle of his letters. Much of this section comes from correspondence, though there is some formal verse. Several pieces are parodies, some one-off squibs, some full-length. Byron’s distaste for most of the poets of his day shines through, with the recurrent and well-worn traditional joke that their books will end either as stuffing in hatshops, wrapped around pastries, or as toilet-tissue. Byron admired the English poets of the past – the Augustans especially – much more than he did any of his contemporaries. Of “the Romantic Movement” he knew no more than did any of the other writers supposed now to have been members of it. Southey he loathed, as a dreadful doppelgänger – see below. Of Wordsworth he also had a low opinion, based largely on The Excursion – to the ambitions of which Don Juan can be regarded as a riposte (there are as many negative comments about Wordsworth in Don Juan as there are about Southey). He was as abusive of Keats as it’s possible to be, and only relented (as he said), when Shelley showed him Hyperion. Of the poetry of his friend Shelley he was very guarded indeed, and compensated by defending Shelley’s moral reputation. Blake he seems not to have known (“Blake” was him the name of a well-known Fleet Street barber). The only poet of whom his judgement and modern estimate coincide is Coleridge: he was strong in his admiration for The Ancient Mariner, Kubla Khan, and Christabel; about the conversational poems he seems blank, and he feigns total incomprehension of the Biographia Literaria (see below). -

Sir James Alfred Ewing, K.C.B., M.A., D.Sc, LL.D., F.R.S

150 Obituary Notices. Sir James Alfred Ewing, K.C.B., M.A., D.Sc, LL.D., F.R.S. JAMES ALFRED EWING, a great engineer, scientific man, and charming Scot, was distinguished in many fields of activity. Born in 1855 at Dundee, where his father was a minister of the Free Church of Scotland, he grew up in an intellectual and spiritual atmosphere in which his early education was greatly influenced by his mother, whose critical taste in letters was passed on to her children. From Dundee High School Ewing proceeded in the early seventies to the University of Edinburgh, where his great ability soon manifested itself in the classes of Tait and Fleeming Jenkin, the latter of whom brought him into touch with Sir William Thomson (afterwards Lord Kelvin), then engaged in the development of submarine telegraph cables, an introduction which led to Ewing taking part in three cable-laying voyages to Brazil and the River Plate. Fleeming Jenkin was a man of wide culture, and his literary and scientific circle included Ewing and another young student, Robert Louis Stevenson, then at the commence- ment of an engineering training, soon to be abandoned for a literary career of the greatest distinction, the beginnings of which have been happily described by Ewing in "The Fleeming Jenkins and Robert Louis Steven- son." In 1878, at the early age of twenty-three, Ewing went to Japan as Professor of Mechanical Engineering in the University of Tokyo, a post which he occupied for five years, and there he made his classical researches in the widely different fields of magnetism and seismology. -

9/15 JEFFREY JAMES HENDERSON William Goodwin Aurelio Professor

9/15 JEFFREY JAMES HENDERSON William Goodwin Aurelio Professor of Greek Language and Literature General Editor, Loeb Classical Library Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences Department of Classical Studies 460 Park Drive Boston University Boston, MA 02215 745 Commonwealth Avenue, Rm. 435 (857) 250-4216 Boston, MA 02215 (617) 358-5072 or 2427 email: [email protected] EDUCATION PhD 1972 Harvard University MA 1970 Harvard University BA 1968 Kenyon College (summa cum laude) POSITIONS HELD Visiting Professor Spring 2010 Brown University Aurelio Professor of Greek 2002-- Boston University Dean of Arts and Sciences 2002-07 Boston University Professor and Chair 1991-2002 Boston University Visiting Professor 1986 Univ. California at Los Angeles Professor 1986-91 Univ. Southern California Associate Professor 1983-86 Univ. Southern California Visiting Professor 1982-83 Univ. Southern California Associate Professor 1978-82 Univ. of Michigan (Ann Arbor) Assistant Professor 1972-78 Yale University ACADEMIC HONORS Kenyon College Highest Honors in Classics Brain Prize in Classics Essay Prize in English Phi Beta Kappa Harvard Univ. Bowdoin Prize in Latin Prose Composition PRIZES AND HONORS Raubenheimer Distinguished Faculty Award (1991) University of Southern California Doctor of Humane Letters (1994) Kenyon College Charles J. Goodwin Award of Merit (2002) American Philological Association Fellow, American Academy of Arts and Sciences elected 2011 eProduct/Best in Humanities (2015) for digital LCL American Publishers Awards for Professional and Scholarly -

Middle Comedy: Not Only Mythology and Food

Acta Ant. Hung. 56, 2016, 421–433 DOI: 10.1556/068.2016.56.4.2 VIRGINIA MASTELLARI MIDDLE COMEDY: NOT ONLY MYTHOLOGY AND FOOD View metadata, citation and similar papersTHE at core.ac.ukPOLITICAL AND CONTEMPORARY DIMENSION brought to you by CORE provided by Repository of the Academy's Library Summary: The disappearance of the political and contemporary dimension in the production after Aris- tophanes is a false belief that has been shared for a long time, together with the assumption that Middle Comedy – the transitional period between archaia and nea – was only about mythological burlesque and food. The misleading idea has surely risen because of the main source of the comic fragments: Athenaeus, The Learned Banqueters. However, the contemporary and political aspect emerges again in the 4th c. BC in the creations of a small group of dramatists, among whom Timocles, Mnesimachus and Heniochus stand out (significantly, most of them are concentrated in the time of the Macedonian expansion). Firstly Timocles, in whose fragments the personal mockery, the onomasti komodein, is still present and sharp, often against contemporary political leaders (cf. frr. 17, 19, 27 K.–A.). Then, Mnesimachus (Φίλιππος, frr. 7–10 K.–A.) and Heniochus (fr. 5 K.–A.), who show an anti- and a pro-Macedonian attitude, respec- tively. The present paper analyses the use of the political and contemporary element in Middle Comedy and the main differences between the poets named and Aristophanes, trying to sketch the evolution of the genre, the points of contact and the new tendencies. Key words: Middle Comedy, Politics, Onomasti komodein For many years, what is known as the “food fallacy”1 has been widespread among scholars of Comedy. -

Ernani Program

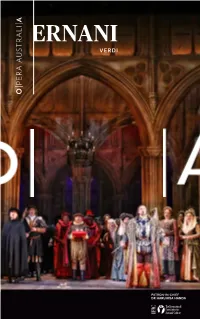

VERDI PATRON-IN-CHIEF DR HARUHISA HANDA Celebrating the return of World Class Opera HSBC, as proud partner of Opera Australia, supports the many returns of 2021. Together we thrive Issued by HSBC Bank Australia Limited ABN 48 006 434 162 AFSL No. 232595. Ernani Composer Ernani State Theatre, Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) Diego Torre Arts Centre Melbourne Librettist Don Carlo, King of Spain Performance dates Francesco Maria Piave Vladimir Stoyanov 13, 15, 18, 22 May 2021 (1810-1876) Don Ruy Gomez de Silva Alexander Vinogradov Running time: approximately 2 hours and 30 Conductor Elvira minutes, including one interval. Carlo Montanaro Natalie Aroyan Director Giovanna Co-production by Teatro alla Scala Sven-Eric Bechtolf Jennifer Black and Opera Australia Rehearsal Director Don Riccardo Liesel Badorrek Simon Kim Scenic Designer Jago Thank you to our Donors Julian Crouch Luke Gabbedy Natalie Aroyan is supported by Costume Designer Roy and Gay Woodward Kevin Pollard Opera Australia Chorus Lighting Designer Chorus Master Diego Torre is supported by Marco Filibeck Paul Fitzsimon Christine Yip and Paul Brady Video Designer Assistant Chorus Master Paul Fitzsimon is supported by Filippo Marta Michael Curtain Ina Bornkessel-Schlesewsky and Matthias Schlesewsky Opera Australia Actors The costumes for the role of Ernani in this production have been Orchestra Victoria supported by the Concertmaster Mostyn Family Foundation Sulki Yu You are welcome to take photos of yourself in the theatre at interval, but you may not photograph, film or record the performance. -

John Hookham Frere 1769-1846

JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE 1769-1846 Ta' A. CREMONA FOST il-Meċenti tal-Lsien Malti nistgħu ngħoddu lil JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE li barra mill-imħabba li kellu għall-ilsna barranin, Grieg, Latin, Spanjol, li scudjahom u kien jafhom tajjeb, kien wera ħrara u ħeġġa kbira biex imexxi '1 quddiem l-istudju tal-Malti, kif ukoll tal-ilsna orjentali, fosthom il-Lhudi u l-Għarbi, ma' tul iż-żmien li kien hawn Malta u baqa' hawnhekk sa mewtu. JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE twieled Londra fil-21 ta' Mejju, 1769. FI-1785 beda l-istudji tiegħu fil-Kulleġġ ta' Eton. Niesu mhux dejjem kienu jo qogtldu b'darhom Londra, iżda dlonk ma' tul is-sena kienu jmorru jgħixu ukoll Roydon f'Norfolk u f'Redington f'Surrey. F'Eton, fejn studja l-lette ratura Ingliża, Griega u Latina, kien sar ħabib tal-qalb ta' George Canning li l-ħbiberija tagħhom baqgħet għal għomorhom. Fl-1786, flimkien ma' xi studenti tal-Kulleġġ [la sehem fil-pubblikazzjoni tar-u vista Microcosm li bil-kitba letterar;a li kien fiha kienet ħadet isem fost l-istudenti ta' barra -il-kulleġġ. Minn Eton, Hookham Frere kien daħal f'Caius College, f'Cam bridge, fejn ħa l-grad tal-Baċellerat tal-Arti 8-1792 u l-Magister Artium fl-1795, u kiseb ie-titlu ta' Fellow of Caius għall-kitba tiegħu klassika ta' proża u versi. Fl-1797 issieħeb ma' Canning u xi żgħażagħ oħra fil-pub blikazzjoni tal-ġumal Anti-] acobin li kien joħroġ kull ġimgħa, nhar ta' Tnejn, bil-ħsieb li jrażżan il-propaganda tal-Partit Republikan Franċiż li kien qed ihedded il-monarkija tal-Istati Ewropej bil-filosofija Ġakbina tiegħu. -

Sess. Professor Andrew Jamieson, M.Inst

334 Proceedings of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. [Sess. Professor Andrew Jamieson, M.Inst.C.E. By Mr J. Wilson. (Read January 20, 1913.) PROFESSOR JAMIESON, M.Inst.C.E., whose death took place on the 4th December 1912, at his residence, 16 Rosslyn Terrace, Kelvinside, Glasgow, W., was well known throughout the country as a consulting engineer and as the author of a large number of standard text-books on electrical and engineering subjects. He was elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society of Edinburgh in 1882. Professor Jamieson, who was the eldest son of the late Rev. George Jamieson, D.D., of Old Machar Cathedral, Aberdeen, was born at Grange, Banffshire, in 1849, and received his education at the Gymnasium, Old Aberdeen, and at Aberdeen University. His apprenticeship was served with Messrs Hall, Russel & Co., marine engineers and shipbuilders, Aberdeen Ironwork. He afterwards entered the service of the Great North of Scotland Railway Company, ultimately attaining the position of chief draughtsman in the loco, and carriage department. When only twenty-three years of age he was appointed assistant to Sir William Thomson (Lord Kelvin) and Professor Fleeming Jenkin, who placed him in charge of the testing staff, to supervise the manufacture of the submarine cables at the Woolwich works of Messrs Siemens Bros. Then followed several years during which Mr Jamieson was mostly abroad. For two years he acted as chief electrical assistant to Thomson and Jenkin, along the coast of Brazil, for the Western Brazilian, and Platino-Brazilian Companies. On returning to this country, the late Sir John Pender and Sir James Anderson appointed him chief electrician to the Eastern Telegraph Company, and he was sent to the Mediterranean to super- intend the laying of the Marseilles-Malta cable. -

Thucydides, Book 6. Edited by E.C. Marchant

^ Claasiral ^nits^ ( 10 THUCYDIDES BOOK VI THUCYDIDES BOOK VI EDITED BY E. C. MAECHANT, M.A. TRINITY COLLEGE, OXFORD ASSISTANT-MASTER IN ST. PAUL'S SCHOOL FELLOW AND LATE ASSISTANT-TUTOR OF PETEBHOUSE, CAMBRIDGE LATE PROFESSOR OF GREEK AND ANCIENT HISTORY IN QUEEN'S COLLEGE, \ LONDON fLontron MACMILLAN AND CO., Lt NEW YORK : THE MACMILLAN CO. 1897 ftd>c • FRIDERICO • GVLIELMO WALKER VI RO NVLLA EGENTI LAVDATIONE ET IVVBNTVTI FIDE ET LITERARVM STVDI08AE I CONTENTS PAQK Introduction— I. The Sicilian Expedition ix II. The MSS. and Text of the Sixth Book . iviii III. Some Graces xxx IV. Criticism of the Book in detail . xli Text 1 Notes US Appendix—On the Speech of Alcibiades, cc. 89-92 . 255 Index—Greek 259 English 294 INTRODUCTION I. Remarks on the Sicilian Expedition Intervention in —It is to § 1. Athenian Sicily. usual classify the states of antiquity according to the character of their government, and for Greek history down to the Peloponnesian War (431-404) this classification, derived from the teaching of Aristotle, is essential. But during the war the essential dis- tinction is not between oligarchy and democracy : it is much more between Ionian and Dorian. What is held to draw states into united action is the natural bond of common origin. In practice the artificial bond of common interest may prove as strong or stronger than the natural bond, and may lead to alliance between aliens or enmity between kinsmen. In order to understand the transactions between the independent states, we have to banish from our minds the elaborate rules that constitute modern Inter- national Law. -

Laughter from Hades: Aristophanic Voice Today*

51 Ifigenija Radulović University of Novi Sad, Serbia Ismene Helen Radoulovits Petkovits National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, Greece Laughter from Hades: Aristophanic Voice Today The current Greek political situation again brings to light, and on stage, many ancient dramas. Contemporary Greek theatre professionals, not turning a blind eye to reality, have come up with ‘the revival’ of old texts, staging them in new circumstances. Aristophaniad is an original play with a subversive content inspired by Aristophanes and a contemporary street graffito reflecting contemporary Athenian life. It is a mixture of various comic and other dramatic elements, such as ancient comedy, grotesque, pantomime, musical, ballet, opera, standup, even circus. Additionally, staging methods developed by the Greek director, Karolos Koun (1908‐1987) are also evident in the production. Idea Theatre Company, exploiting excerpts from Aristophanes’ plays and starring the comediographer himself, manages to depict a fictional and real world in one. The performance starts with the rehearsal of Aristophanes’ new play, Poverty, which is in danger of being left unfinished since Hades plans to take Aristophanes to the Underworld. The play ends with Plutus. In the meantime, the performance entertains its audience, leading them to experience Aristotelian catharsis through laughter. This collective ‘purification’ of the soul is supposed to be mediated by laughter and provoked by references to serious life issues, given in comic mode and through a vast range of human emotions. The article deals with those comic features and supports the thesis that in spite of the fact that times change, people never cease to fight for a better society. -

Rethinking Athenian Democracy.Pdf

Rethinking Athenian Democracy A dissertation presented by Daniela Louise Cammack to The Department of Government in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Political Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2013 © 2013 Daniela Cammack All rights reserved. Professor Richard Tuck Daniela Cammack Abstract Conventional accounts of classical Athenian democracy represent the assembly as the primary democratic institution in the Athenian political system. This looks reasonable in the light of modern democracy, which has typically developed through the democratization of legislative assemblies. Yet it conflicts with the evidence at our disposal. Our ancient sources suggest that the most significant and distinctively democratic institution in Athens was the courts, where decisions were made by large panels of randomly selected ordinary citizens with no possibility of appeal. This dissertation reinterprets Athenian democracy as “dikastic democracy” (from the Greek dikastēs, “judge”), defined as a mode of government in which ordinary citizens rule principally through their control of the administration of justice. It begins by casting doubt on two major planks in the modern interpretation of Athenian democracy: first, that it rested on a conception of the “wisdom of the multitude” akin to that advanced by epistemic democrats today, and second that it was “deliberative,” meaning that mass discussion of political matters played a defining role. The first plank rests largely on an argument made by Aristotle in support of mass political participation, which I show has been comprehensively misunderstood. The second rests on the interpretation of the verb “bouleuomai” as indicating speech, but I suggest that it meant internal reflection in both the courts and the assembly.