Poems About Poets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Hookham Frere 1769-1846

JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE 1769-1846 Ta' A. CREMONA FOST il-Meċenti tal-Lsien Malti nistgħu ngħoddu lil JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE li barra mill-imħabba li kellu għall-ilsna barranin, Grieg, Latin, Spanjol, li scudjahom u kien jafhom tajjeb, kien wera ħrara u ħeġġa kbira biex imexxi '1 quddiem l-istudju tal-Malti, kif ukoll tal-ilsna orjentali, fosthom il-Lhudi u l-Għarbi, ma' tul iż-żmien li kien hawn Malta u baqa' hawnhekk sa mewtu. JOHN HOOKHAM FRERE twieled Londra fil-21 ta' Mejju, 1769. FI-1785 beda l-istudji tiegħu fil-Kulleġġ ta' Eton. Niesu mhux dejjem kienu jo qogtldu b'darhom Londra, iżda dlonk ma' tul is-sena kienu jmorru jgħixu ukoll Roydon f'Norfolk u f'Redington f'Surrey. F'Eton, fejn studja l-lette ratura Ingliża, Griega u Latina, kien sar ħabib tal-qalb ta' George Canning li l-ħbiberija tagħhom baqgħet għal għomorhom. Fl-1786, flimkien ma' xi studenti tal-Kulleġġ [la sehem fil-pubblikazzjoni tar-u vista Microcosm li bil-kitba letterar;a li kien fiha kienet ħadet isem fost l-istudenti ta' barra -il-kulleġġ. Minn Eton, Hookham Frere kien daħal f'Caius College, f'Cam bridge, fejn ħa l-grad tal-Baċellerat tal-Arti 8-1792 u l-Magister Artium fl-1795, u kiseb ie-titlu ta' Fellow of Caius għall-kitba tiegħu klassika ta' proża u versi. Fl-1797 issieħeb ma' Canning u xi żgħażagħ oħra fil-pub blikazzjoni tal-ġumal Anti-] acobin li kien joħroġ kull ġimgħa, nhar ta' Tnejn, bil-ħsieb li jrażżan il-propaganda tal-Partit Republikan Franċiż li kien qed ihedded il-monarkija tal-Istati Ewropej bil-filosofija Ġakbina tiegħu. -

Download Download

An “imperfect” Model of Authorship in Dorothy Wordsworth’s Grasmere Journal HEATHER MEEK Abstract: This essay explores Dorothy Wordsworth’s collaborative, “pluralist” model of selfhood and authorship as it is elaborated in her Grasmere journal (1800-03). Nature and community, for her, are extensions of the self rather than (as they often are for her brother William) external forces to be subsumed by the self of the solitary artist. This model, however, is the site of ambivalence and conflict, and is therefore “imperfect” – a word Wordsworth herself uses to qualify the “summary” she believes her journal as a whole provides. It is “imperfect” not because it is inferior, weak, or deficient in some way, but because it is riddled with tension and inconsistency. Wordsworth embraces processes of collaborative creativity, but she also expresses – largely through her narrations of illness – dissatisfaction with such processes, and she sometimes finds relief in her solitary, melancholic musings. In these ways, she at once subverts, reworks, and reinforces conventional, ‘solitary genius’ paradigms of authorship. Contributor Biography: Heather Meek is Assistant Professor of English in the Department of Literatures and Languages of the World, Université de Montréal. Her research and teaching interests include eighteenth-century women’s writing, medical treatises, mental illness, and the intersections of literature and medicine. Dorothy Wordsworth’s well-known claim in an 1810 letter to her friend Catherine Clarkson – “I should detest the idea of setting myself up as an Author” (Letters 454) – has by now been interrogated at length. A survey of Dorothy Wordsworth scholarship of the past thirty years reveals that understandings of her as William’s self-effacing, silenced sister, one who was “constantly denigrat[ing] herself and her talent” (Levin, Romanticism 4), and who, despite poet Samuel Rogers’ urging, never viewed herself as a writer (Hamilton xix), have been largely dismissed. -

1815 1817 George Gordon, Lord Byron 1788-1824

http://www.englishworld2011.info/ GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON / 607 (by which last I mean neither rhythm nor metre) this genus comprises as its species, gaming; swinging or swaying on a chair or gate; spitting over a bridge; smoking; snuff-taking; tete-a-tete quarrels after dinner between husband and wife; conning word by word all the advertisements of the Daily Advertiser in a public house on a rainy day, etc. etc. etc. 1815 1817 GEORGE GORDON, LORD BYRON 1788-1824 In his History of English Literature, written in the late 1850s, the French critic Hip- polyte Taine gave only a few condescending pages to Wordsworth, Coleridge, Percy Shelley, and Keats and then devoted a long chapter to Lord Byron, "the greatest and most English of these artists; he is so great and so English that from him alone we shall learn more truths of his country and of his age than from all the rest together." This comment reflects the fact that Byron had achieved an immense European rep- utation during his own lifetime, while admirers of his English contemporaries were much more limited in number. Through much of the nineteenth century he contin- ued to be rated as one of the greatest of English poets and the very prototype of literary Bomanticism. His influence was manifested everywhere, among the major poets and novelists (Balzac and Stendhal in France, Pushkin and Dostoyevsky in Russia, and Melville in America), painters (especially Delacroix), and composers (including Beethoven and Berlioz). Yet even as poets, painters, and composers across Europe and the Americas struck Byronic attitudes, Byron's place within the canon of English Bomantic poetry was becoming insecure. -

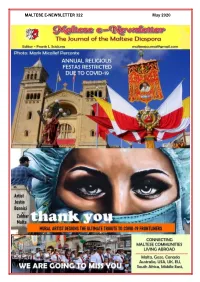

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020

MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 1 MALTESE E-NEWSLETTER 322 May 2020 French Occupation of Malta Malta and all of its resources over to the French in exchange for estates and pensions in France for himself and his knights. Bonaparte then established a French garrison on the islands, leaving 4,000 men under Vaubois while he and the rest of the expeditionary force sailed eastwards for Alexandria on 19 June. REFORMS During Napoleon's short stay in Malta, he stayed in Palazzo Parisio in Valletta (currently used as the Ministry for Foreign Affairs). He implemented a number of reforms which were The French occupation of The Grandmaster Ferdinand von based on the principles of the Malta lasted from 1798 to 1800. It Hompesch zu Bolheim, refused French Revolution. These reforms was established when the Order Bonaparte's demand that his could be divided into four main of Saint John surrendered entire convoy be allowed to enter categories: to Napoleon Bonaparte following Valletta and take on supplies, the French landing in June 1798. insisting that Malta's neutrality SOCIAL meant that only two ships could The people of Malta were granted FRENCH INVASION OF MALTA enter at a time. equality before the law, and they On 19 May 1798, a French fleet On receiving this reply, Bonaparte were regarded as French citizens. sailed from Toulon, escorting an immediately ordered his fleet to The Maltese nobility was expeditionary force of over bombard Valletta and, on 11 June, abolished, and slaves were freed. 30,000 men under General Louis Baraguey Freedom of speech and the press General Napoleon Bonaparte. -

Art and Samuel Rogers's Italy

Reverse Pygmalionism Art and Samuel Rogers’s Italy ANGOR UNIVERSITY McCue, M. Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840 PRIFYSGOL BANGOR / B Published: 01/01/2013 Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Cyswllt i'r cyhoeddiad / Link to publication Dyfyniad o'r fersiwn a gyhoeddwyd / Citation for published version (APA): McCue, M. (2013). Reverse Pygmalionism Art and Samuel Rogers’s Italy. Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 21. Hawliau Cyffredinol / General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. 26. Sep. 2021 ROMANTICT EXTUALITIES LITERATURE AND PRINT CULTURE, 1780–1840 • Issue 21 (Winter 2013) Centre for Editorial and Intertextual Research Cardiff University RT21.indb 1 16/07/2014 04:53:34 Romantic Textualities is available on the web at www.romtext.org.uk, and on Twitter @romtext ISSN 1748-0116 Romantic Textualities: Literature and Print Culture, 1780–1840, 21 (Winter 2013). -

Nervous Sympathy in the Familial Collaborations of the Wordsworth

The Mediated Self: Nervous Sympathy in the Familial Collaborations of the Wordsworth- Lamb-Coleridge Circle, 1799-1852 Katherine Olivia Ingle MA (University of Edinburgh) MScR (University of Edinburgh) English & Creative Writing Lancaster University November 2018 This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature. Katherine Olivia Ingle ii I declare that this thesis was composed by myself, that the work contained herein is my own except where explicitly stated otherwise in the text, and that this work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. November 2018 Katherine Olivia Ingle iii This thesis is dedicated with love to my grandmothers, Cynthia Ingle and Doreen France & in loving memory of my grandfathers, Thomas Ian Ingle, 1925-2014 & Joseph Lees France, 1929-2017 There is a comfort in the strength of love; ‘Twill make a thing endurable, which else Would overset the brain, or break the heart. Wordsworth, “Michael” Katherine Olivia Ingle iv Acknowledgements This thesis could not have taken shape without the attention, patience and encouragement of my supervisor Sally Bushell. I am deeply grateful to her for helping me to clarify ideas and for teaching me that problems are good things. I thank Sally in her numerous capacities as a Wordsworthian scholar, reader, teacher and friend. I am grateful to the Department of English & Creative Writing at Lancaster for a bursary towards an archival visit to the Jerwood Centre at The Wordsworth Trust. I thank the Curator, Jeff Cowton, for his generosity, insights and valuable suggestions. -

Blue Banner Faith and Life

BLUE BANNER FAITH AND LIFE J. G. VOS, Editor and Manager Copyright © 2016 The Board of Education and Publication of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (Crown & Covenant Publications) 7408 Penn Avenue • Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15208 All rights are reserved by the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America and its Board of Education & Publication (Crown & Covenant Publications). Except for personal use of one digital copy by the user, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the prior written permission of the publisher. This project is made possible by the History Committee of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America (rparchives.org). BLUE BANNER FAITH AND LIFE VOLUME 9 JANUARY-MARCH, 1954 NUMBER 1 “A wonderful and horrible thing is committed in the land; the prophets prophesy falsely, and the priests bear rule by their means; and my people love to have it so: and what will ye do in the end thereof?” Jeremiah 5:30,31 A Quarterly Publication Devoted to Expounding, Defending and Applying the System of Doctrine set forth in the Word of God and Summarized in the Standards of the Reformed Presbyterian (Covenanter) Church. Subscription $1.50 per year postpaid anywhere J. G. Vos, Editor and Manager Route 1 Clay Center, Kansas, U.S.A. Editorial Committee: M. W. Dougherty, R, W. Caskey, Ross Latimer Published by The Board of Publication of the Synod of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America Agent for Britain and Ireland: The Rev. -

Byron's Library

1 BYRON’S LIBRARY: THE THREE BOOK SALE CATALOGUES Edited and introduced by Peter Cochran The 1813 Catalogue Throughout much of 1813, Byron was planning to go east again, not with Hobhouse this time, but with the Marquis of Sligo, who, just out of jail for abducting sailors during a period of war, was anxious to be away from the public gaze. They never went: the difficulty of finding adequate transport for themselves and their retinues, plus a report of plague in the Levant, prevented them. Sligo would have had difficulty in any case getting passage on an English ship of war. However, just how close they got to leaving is shown by the first of the three catalogues below. While still adding lines to The Giaour, Byron was within an ace of selling his library. Its catalogue is headed: A / CATALOGUE OF BOOKS, / THE PROPERTY OF A NOBLEMAN [in ink in margin: Lord Byron / J.M.] / ABOUT TO LEAVE ENGLAND / ON A TOUR OF THE MOREA. / TO WHICH ARE ADDED / A SILVER SEPULCHRAL URN, / CONTAINING / RELICS BROUGHT FROM ATHENS IN 1811, / AND / A SILVER CUP, / THE PROPERTY OF THE SAME NOBLE PERSON; / WHICH WILL BE / SOLD BY AUCTION / BY R. H. EVANS / AT HIS HOUSE, No. 26, PALL-MALL, / On Thursday July 8th, and following Day. Catalogues may be had, and the Books viewed at the / Place of Sale. / Printed by W.Bulmer and Co. Cleveland-row, St. James’ s. / 1813. It’s not usual to sell your entire library before going abroad unless you intend never to return. -

Poesía Inglesa De La Guerra De La Independencia (1808-1814). Antología Bilingüe, Madrid, Fundación Dos De Mayo - Espasa, 387 Pp

Cuadernos de Ilustración y Romanticismo Revista Digital del Grupo de Estudios del Siglo XVIII Universidad de Cádiz / ISSN: 2173-0687 nº 20 (2014) Agustín COLETES BLANCO y Alicia LASPRA RODRÍGUEZ (2013), Libertad frente a tiranía: poesía inglesa de la Guerra de la Independencia (1808-1814). Antología bilingüe, Madrid, Fundación Dos de Mayo - Espasa, 387 pp. Readers of Cuadernos will need little introduction to this Anglo-Spanish anthology; the first installment of a major project to recover the English, French, Portuguese and German poems written about Spain during the Peninsular War. Edited by Agustín Coletes Blanco and Alicia Laspra Rodríguez, Libertad frente a tiranía: poesía inglesa de la Guerra de la Independencia (1808-1814) makes a noble defence for the poetry published during this period: «Poesía, porque se trata de un género literario que implica inmediatez y fuerza expresiva en la respuesta y, por tanto, en la mediación entre el autor y el público» (25). Such expressiveness is a feature not only of the English poems chosen for inclusion, but of the editors’ own sensitively considered translations. Libertad Frente a Tiranía is an anthology divided into three parts. Part 1 offers a comprehensive selection of the Spanish- themed war poems written by authors such as Wordsworth, Byron, Scott, and Southey, now considered canonical («los poetas consagrados»); the second focuses on poets who enjoyed contemporary celebrity («los autores relevantes en su época»); while Part 3 is devoted to the largely anonymous (or at least pseudonymous) publications that appeared in contemporary British newspapers and periodicals («poesía publicada en prensa»). This division is, for the most part, successful; prompting http://dx.doi.org/10.25267/Cuad_Ilus_Romant.2014.i20.28 important questions about the perceived quality, contemporary demand for, and initial reception of these recovered poems. -

03-26-21 Choral Conc Rec Lchaim

FSU CHAMBER SINGERS UNIVERSITY CHORALE TROUBADOURS DR.SCOTT RIEKER, CONDUCTOR DR. JOSEPH YUNGEN, PIANO FEATURING Cantor Richard Bessman (B’er Chayim) Friday March 26, 2021 Pealer Recital Hall 7:30 p.m. Woodward D. Pealer Performing Arts Center PROGRAM Psalm 23 ............................................................................................................................................ Max Wohlberg Richard Bessman, baritone (1907–1996) UNIVERSITY CHORALE Wana Baraka ............................................................................................................................. arr. Shawn Kirchner Nathan Richards, conductor (b. 1970) Adon Olam No. 1 from Shir Zion .................................................................................................... Salomon Sulzer Kristen Feaster, conductor (1804–1890) Mizmor le David (Psalm 23) ............................................................................................................ Moshe S. Knoll Hannah PolK, conductor (b. 1960) Haleluyah haleli (Psalm 146) ........................................................................................................... Salamone Rossi (1570–c.1630) Avodath Hakodesh ................................................................................................................................ Ernest Bloch V. Benediction Richard Bessman, baritone (1880–1959) TROUBADOURS Hine Ma Tov ................................................................................................................................ -

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 a Sermon Preached Before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26

BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 A sermon preached before the Right Honourable the House of Peeres in the Abbey at Westminster, the 26. of November, 1645 / by Jer.Burroughus. - London : printed for R.Dawlman, 1646. -[6],48p.; 4to, dedn. - Final leaf lacking. Bound with r the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S. SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 438 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons assembled in Parliament at their publique thanksgiving September 7 1641 for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. - [8],64p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : Gauden, J. The love of truth and peace. London, 1641. 1S.SERMONS BURROUGHS, Jeremiah, 1599-1646 I 656 Sions joy : a sermon preached to the honourable House of Commons, September 7.1641, for the peace concluded between England and Scotland / by Jeremiah Burroughs. - London : printed by T.P. and M.S. for R.Dawlman, 1641. -[8],54p.; 4to, dedn. - Bound with : the author's Moses his choice. London, 1650. 1S.SERMONS BURT, Edward, fl.1755 D 695-6 Letters from a gentleman in the north of Scotland to his friend in London : containing the description of a capital town in that northern country, likewise an account of the Highlands. - A new edition, with notes. - London : Gale, Curtis & Fenner, 1815. - 2v. (xxviii, 273p. : xii,321p.); 22cm. - Inscribed "Caledonian Literary Society." 2.A GENTLEMAN in the north of Scotland. 3S.SCOTLAND - Description and travel I BURTON, Henry, 1578-1648 K 140 The bateing of the Popes bull] / [by HenRy Burton], - [London?], [ 164-?]. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher.