NV Musk Deer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World at the Time of Messel: Conference Volume

T. Lehmann & S.F.K. Schaal (eds) The World at the Time of Messel - Conference Volume Time at the The World The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 2011 Frankfurt am Main, 15th - 19th November 2011 ISBN 978-3-929907-86-5 Conference Volume SENCKENBERG Gesellschaft für Naturforschung THOMAS LEHMANN & STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL (eds) The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference Frankfurt am Main, 15th – 19th November 2011 Conference Volume Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung IMPRINT The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates 22nd International Senckenberg Conference 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main, Germany Conference Volume Publisher PROF. DR. DR. H.C. VOLKER MOSBRUGGER Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany Editors DR. THOMAS LEHMANN & DR. STEPHAN F.K. SCHAAL Senckenberg Research Institute and Natural History Museum Frankfurt Senckenberganlage 25, 60325 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] Language editors JOSEPH E.B. HOGAN & DR. KRISTER T. SMITH Layout JULIANE EBERHARDT & ANIKA VOGEL Cover Illustration EVELINE JUNQUEIRA Print Rhein-Main-Geschäftsdrucke, Hofheim-Wallau, Germany Citation LEHMANN, T. & SCHAAL, S.F.K. (eds) (2011). The World at the Time of Messel: Puzzles in Palaeobiology, Palaeoenvironment, and the History of Early Primates. 22nd International Senckenberg Conference. 15th – 19th November 2011, Frankfurt am Main. Conference Volume. Senckenberg Gesellschaft für Naturforschung, Frankfurt am Main. pp. 203. -

Short Title: Ecological Properties of Ruminal Microbiota

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 24 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0628.v1 CHARACTERISTICS OF RUMINAL MICROBIAL COMMUNITY: EVOLUTIONARY AND ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES AMLAN KUMAR PATRA* Department of Animal Nutrition, West Bengal University of Animal and Fishery Sciences, Belgachia, K.B. Sarani 37, Kolkata 700037, India *Corresponding author. Email address: [email protected] (A.K. Patra) Short title: Ecological properties of ruminal microbiota 0 © 2020 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 24 December 2020 doi:10.20944/preprints202012.0628.v1 CHARACTERISTICS OF RUMINAL MICROBIAL COMMUNITY: EVOLUTIONARY AND ECOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES Abstract Ruminants perhaps appeared about 50 million years ago (Ma). Five ruminant families had been extinct and about 200 species in 6 ruminant families are living today. The first ruminant family probably was small omnivore without functional ruminal microbiota to digest fiber. Subsequently, other ruminant families evolved around 18-23 Ma along with woodlands and grasslands. Probably, ruminants started to consume selective and highly nutritious plant leaves and grasses similar to concentrates. By 5-11 Ma, grasslands expanded and some ruminants used more grass in their diets with comparatively low nutritive values and high fibers. Historically, humans have domesticated 9 ruminant species that are mostly utilizer of low quality forages for human benefits. Thus, the non-functional rumen microbiota to predominantly concentrate fermenting microbiota, followed by predominantly fiber digesting microbiota had evolved for mutual complementary benefits of holobiont over the million years. The core microbiome of ruminant species seems the resultant of hologenome interaction in an evolutionary unit. -

71St Annual Meeting Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Paris Las Vegas Las Vegas, Nevada, USA November 2 – 5, 2011 SESSION CONCURRENT SESSION CONCURRENT

ISSN 1937-2809 online Journal of Supplement to the November 2011 Vertebrate Paleontology Vertebrate Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Society of Vertebrate 71st Annual Meeting Paleontology Society of Vertebrate Las Vegas Paris Nevada, USA Las Vegas, November 2 – 5, 2011 Program and Abstracts Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 71st Annual Meeting Program and Abstracts COMMITTEE MEETING ROOM POSTER SESSION/ CONCURRENT CONCURRENT SESSION EXHIBITS SESSION COMMITTEE MEETING ROOMS AUCTION EVENT REGISTRATION, CONCURRENT MERCHANDISE SESSION LOUNGE, EDUCATION & OUTREACH SPEAKER READY COMMITTEE MEETING POSTER SESSION ROOM ROOM SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL MEETING PARIS LAS VEGAS HOTEL LAS VEGAS, NV, USA NOVEMBER 2–5, 2011 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Rowland, Co-Chair; Aubrey Bonde, Co-Chair; Joshua Bonde; David Elliott; Lee Hall; Jerry Harris; Andrew Milner; Eric Roberts EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Philip Currie, President; Blaire Van Valkenburgh, Past President; Catherine Forster, Vice President; Christopher Bell, Secretary; Ted Vlamis, Treasurer; Julia Clarke, Member at Large; Kristina Curry Rogers, Member at Large; Lars Werdelin, Member at Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Roger B.J. Benson, Richard J. Butler, Nadia B. Fröbisch, Hans C.E. Larsson, Mark A. Loewen, Philip D. Mannion, Jim I. Mead, Eric M. Roberts, Scott D. Sampson, Eric D. Scott, Kathleen Springer PROGRAM COMMITTEE Jonathan Bloch, Co-Chair; Anjali Goswami, Co-Chair; Jason Anderson; Paul Barrett; Brian Beatty; Kerin Claeson; Kristina Curry Rogers; Ted Daeschler; David Evans; David Fox; Nadia B. Fröbisch; Christian Kammerer; Johannes Müller; Emily Rayfield; William Sanders; Bruce Shockey; Mary Silcox; Michelle Stocker; Rebecca Terry November 2011—PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Members and Friends of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology, The Host Committee cordially welcomes you to the 71st Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology in Las Vegas. -

Species Were Accidentally Lost,But Future Shipments Will Probably

59.9(728) Article XXXIV.- MAMMALS FROM NICARAGUA. BY J. A. ALLEN. During the last two years the Museum has received several collections of birds and mammals from Nicaragua, made by Mr. William B. Richardson, who for many years was in the employ of Messrs. Salvin and Godman as an ornithological collector in Mexico and Central America. The mammals thus far received comprise about 400 specimens, representing nearly 60 species, of which about one-fourth appear to be undescribed. This is perhaps not surprising, in view of the fact that very few mammals have been previously received from Nicaragua. The most important of Mr. Richardson's discoveries are a new and very distinct species of Bassaricyon, and a new species of spiney rat, allied to the Ecuadorian Echimys gymnurus Thomas, and representing a hitherto unrecognized genus. The collection contains also several other species which are quite differentt from any previously known. Mr. Richardson's collecting trips have covered a wide extent of country. From his home at Matagalpa, in the central part of Nicaragua, he visited the highlands to the northward and northwestward, and also the Pacific coast; eastward his explorations extended from Lake Nicaragua to the vicinity of the Atlantic coast. The principal points at which collections were made are as follows: Matagalpa, altitude about 3000 feet. San Rafael del Norte, altitude about 5000 feet. Ocotal, altitude about 4500 feet. Chinandega, on the Pacific slope, about 700 feet. Chontales, lowlands east of Lake Nicaragua, altitude about 500 to 1000 feet. Tuma and Lavala, east of Matagalpa, on the Atlantic slope, below 1000 feet. -

MALE GENITAL ORGANS and ACCESSORY GLANDS of the LESSER MOUSE DEER, TRAGULUS Fa VAN/CUS

MALE GENITAL ORGANS AND ACCESSORY GLANDS OF THE LESSER MOUSE DEER, TRAGULUS fA VAN/CUS M. K. VIDYADARAN, R. S. K. SHARMA, S. SUMITA, I. ZULKIFLI, AND A. RAZEEM-MAZLAN Faculty of Biomedical and Health Science, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia (MKV), Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, Universiti Putra Malaysia, 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor, Malaysia (RSKS, SS, /Z), Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jmammal/article/80/1/199/844673 by guest on 01 October 2021 Department of Wildlife and National Parks, Zoo Melaka, 75450 Melaka, Malaysia (ARM) Gross anatomical features of the male genital organs and accessory genital glands of the lesser mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) are described. The long fibroelastic penis lacks a prominent glans and is coiled at its free end to form two and one-half turns. Near the tight coils of the penis, on the right ventrolateral aspect, lies a V-shaped ventral process. The scrotum is prominent, unpigmented, and devoid of hair and is attached close to the body, high in the perineal region. The ovoid, obliquely oriented testes carry a large cauda and caput epididymis. Accessory genital glands consist of paired, lobulated, club-shaped vesic ular glands, and a pair of ovoid bulbourethral glands. A well-defined prostate gland was not observed on the surface of the pelvic urethra. Many features of the male genital organs of T. javanicus are pleisomorphic, being retained from suiod ancestors of the Artiodactyla. Key words: Tragulus javanicus, male genital organs, accessory genital glands, reproduc tion, anatomy, Malaysia The lesser mouse deer (Tragulus javan gulidae, and Bovidae (Webb and Taylor, icus), although a ruminant, possesses cer 1980). -

Phylogenetic Relationships and Evolutionary History of the Dental Pattern of Cainotheriidae

Palaeontologia Electronica palaeo-electronica.org A new Cainotherioidea (Mammalia, Artiodactyla) from Palembert (Quercy, SW France): Phylogenetic relationships and evolutionary history of the dental pattern of Cainotheriidae Romain Weppe, Cécile Blondel, Monique Vianey-Liaud, Thierry Pélissié, and Maëva Judith Orliac ABSTRACT Cainotheriidae are small artiodactyls restricted to Western Europe deposits from the late Eocene to the middle Miocene. From their first occurrence in the fossil record, cainotheriids show a highly derived molar morphology compared to other endemic European artiodactyls, called the “Cainotherium plan”, and the modalities of the emer- gence of this family are still poorly understood. Cainotherioid dental material from the Quercy area (Palembert, France; MP18-MP19) is described in this work and referred to Oxacron courtoisii and to a new “cainotherioid” species. The latter shows an intermedi- ate morphology between the “robiacinid” and the “derived cainotheriid” types. This allows for a better understanding of the evolution of the dental pattern of cainotheriids, and identifies the enlargement and lingual migration of the paraconule of the upper molars as a key driver. A phylogenetic analysis, based on dental characters, retrieves the new taxon as the sister group to the clade including Cainotheriinae and Oxacron- inae. The new taxon represents the earliest offshoot of Cainotheriidae. Romain Weppe. Institut des Sciences de l’Évolution de Montpellier, Université de Montpellier, CNRS, IRD, EPHE, Place Eugène Bataillon, 34095 Montpellier Cedex 5, France. [email protected] Cécile Blondel. Laboratoire Paléontologie Évolution Paléoécosystèmes Paléoprimatologie: UMR 7262, Bât. B35 TSA 51106, 6 rue M. Brunet, 86073 Poitiers Cedex 9, France. [email protected] Monique Vianey-Liaud. -

New Remains of Primitive Ruminants from Thailand: Evidence of the Early

ZSC071.fm Page 231 Thursday, September 13, 2001 6:12 PM New0Blackwell Science, Ltd remains of primitive ruminants from Thailand: evidence of the early evolution of the Ruminantia in Asia GRÉGOIRE MÉTAIS, YAOWALAK CHAIMANEE, JEAN-JACQUES JAEGER & STÉPHANE DUCROCQ Accepted: 23 June 2001 Métais, G., Chaimanee, Y., Jaeger, J.-J. & Ducrocq S. (2001). New remains of primitive rumi- nants from Thailand: evidence of the early evolution of the Ruminantia in Asia. — Zoologica Scripta, 30, 231–248. A new tragulid, Archaeotragulus krabiensis, gen. n. et sp. n., is described from the late Eocene Krabi Basin (south Thailand). It represents the oldest occurrence of the family which was pre- viously unknown prior to the Miocene. Archaeotragulus displays a mixture of primitive and derived characters, together with the M structure on the trigonid, which appears to be the main dental autapomorphy of the family. We also report the occurrence at Krabi of a new Lophiomerycid, Krabimeryx primitivus, gen. n. et sp. n., which displays affinities with Chinese representatives of the family, particularly Lophiomeryx. The familial status of Iberomeryx is dis- cussed and a set of characters is proposed to define both Tragulidae and Lophiomerycidae. Results of phylogenetic analysis show that tragulids are monophyletic and appear nested within the lophiomerycids. The occurrence of Tragulidae and Lophiomerycidae in the upper Eocene of south-east Asia enhances the hypothesis that ruminants originated in Asia, but it also challenges the taxonomic status of traguloids within the Ruminantia. Grégoire Métais, Institut des Sciences de l’Evolution, UMR 5554 CNRS, Case 064, Université de Montpellier II, 34095 Montpellier cedex 5, France. -

First Bone-Cracking Dog Coprolites Provide New Insight

RESEARCH ARTICLE First bone-cracking dog coprolites provide new insight into bone consumption in Borophagus and their unique ecological niche Xiaoming Wang1,2,3*, Stuart C White4, Mairin Balisi1,3, Jacob Biewer5,6, Julia Sankey6, Dennis Garber1, Z Jack Tseng1,2,7 1Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, United States; 2Department of Vertebrate Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History, New York, United States; 3Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, United States; 4School of Dentistry, University of California, Los Angeles, United States; 5Department of Geological Sciences, California State University, Fullerton, United States; 6Department of Geology, California State University Stanislaus, Turlock, United States; 7Department of Pathology and Anatomical Sciences, Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, United States Abstract Borophagine canids have long been hypothesized to be North American ecological ‘avatars’ of living hyenas in Africa and Asia, but direct fossil evidence of hyena-like bone consumption is hitherto unknown. We report rare coprolites (fossilized feces) of Borophagus parvus from the late Miocene of California and, for the first time, describe unambiguous evidence that these predatory canids ingested large amounts of bone. Surface morphology, micro-CT analyses, and contextual information reveal (1) droppings in concentrations signifying scent-marking behavior, similar to latrines used by living social carnivorans; (2) routine consumption of skeletons; *For correspondence: (3) undissolved bones inside coprolites indicating gastrointestinal similarity to modern striped and [email protected] brown hyenas; (4) B. parvus body weight of ~24 kg, reaching sizes of obligatory large-prey hunters; ~ Competing interests: The and (5) prey size ranging 35–100 kg. -

Ontogenetic Allometry of the Postcranial Skeleton of the Giraffe (Giraffa Camelopardalis), with Application to Giraffe Life History, Evolution and Palaeontology

Ontogenetic allometry of the postcranial skeleton of the giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis), with application to giraffe life history, evolution and palaeontology By Sybrand Jacobus van Sittert Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Department of Production Animal Studies Faculty of Veterinary Science University of Pretoria Supervisor: Prof Graham Mitchell Former supervisor (deceased): Prof John D Skinner Date submitted: October 2015 i Declaration I, Sybrand Jacobus van Sittert, declare that the thesis, which I hereby submit for the degree Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Pretoria is my own work and has not previously been submitted by me for a degree at this or any other tertiary institution. October 2015 ii Acknowledgements Including a list of people to whom I am grateful to in the acknowledgement section hardly does justice to the respective persons: A thesis is, in all honestly, only comprehensively read by very few people. Nevertheless, it occurred to me that even when I roughly skim through a thesis or dissertation for bits of information, I am always drawn into the acknowledgements. I suppose it is the only section where one can get a glimpse into the life of the researcher in an otherwise rather ‘cold’ academic work. Therefore, although not a large platform to say ‘thank you’, I wish to convey to everyone listed here that you are in the warmest part of my heart … and probably the most read part of my thesis. Prof Graham Mitchell for his patience with me, his guidance, enthusiasm and confidence. I consider myself lucky and honoured to have had you as a supervisor. -

Paleontological Institute, Russian a Cademy of Sciences

Å À . V i s l o b o k o v a a n d  . À . T r o f i m o v Pal eontol ogi cal I nstitute, R ussi an A cadem y of Sciences C ont en t s V oL 3 6, Su p p L 5 , 2 0 02 T he su p p l em en t i s p u b l i sh ed o n l y i n E n g l i sh b y M A I K " N au k a i I n t er p er i o d i c a ' ( R u ssi a) . P a l eo n to l o g i c a l J o u r n a l I S S N 0 0 3 1- 0 30 1. w m o o u c mo x ñí ëðòÅê 1 S43 1 ÒÍ Å H I S T O R Y O F ST U D Y I N G A R C H A E O M E R 1X À Ì > T H E M A I N P R O B L E M S O F P H Y L O G E N Y O F T H E À Ê Ï Î Ð À Ñ ÒÚ× .À $43 1 CHAPTER 2 TAX ONOM IC REV IEW OF THE ARCHAEOMERYCIDAE CHAPTER 3 S44 1 OSTEOL OGY À1×?) OD ONTOL OGY OF ARCHAEOMERYX S44 1 SKUL L S44 1 CRA NIAL BONES S44 8 FACIA L BONES S455 DENT S ON S46 1 DIA ST EM ATA S465 ENA M EL ULTRA STRUCTURE S465 V ERTEBRA L COL UM N S466 S472 FOREL IM B BONES S472 HIND L IM B BONES S4 83 C H A PT E R 4 ì î è í î í ë÷ñ ò þ û ë ò. -

AN AMERICAN FOSSIL GIRAFFE Giraffa Nebrascensis, Sp. Nov

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum, University of Nebraska State Museum 1925 AN AMERICAN FOSSIL GIRAFFE irG affa nebrascensis, sp. nov. W. D. Matthew E. H. Barbour Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/museumbulletin Part of the Entomology Commons, Geology Commons, Geomorphology Commons, Other Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, Paleobiology Commons, Paleontology Commons, and the Sedimentology Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. BULLETIN 4 VOLUME 1 APRIL 1925 THE NEBRASKA STATE MUSEUM ERWIN H. BARBOUR, Director AN AMERICAN FOSSIL GIRAFFE Giraffa nebrascensis, sp. nov. By W. D. MATTHEW E. H. BARBOUR A fragment of the lower jaw of a large fossil mammal with two well-worn teeth was dug up in June 1918, at a depth of 20 feet, while digging a cess pool at Bradshaw, York County, Nebraska. This unique specimen, accessioned 7-7-18, was brought to the Nebraska State Museum by A. Archie Dorsey, and was donated by C. B. Palmet, both of Bradshaw. It undoubtedly occurred in loess, which is thickly as well. as extensively de veloped in this region. It is a ruminant jaw, the teeth preserved being P4 and m 1 • The characteristic pattern of the premolar excludes refer ence to the Bovidae, and leaves the choice between the Gi raffidae, Pa~aeomerycidae, and certain large Cervidae. -

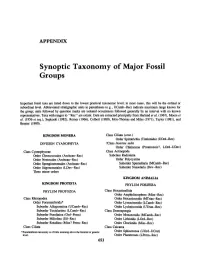

Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups

APPENDIX Synoptic Taxonomy of Major Fossil Groups Important fossil taxa are listed down to the lowest practical taxonomic level; in most cases, this will be the ordinal or subordinallevel. Abbreviated stratigraphic units in parentheses (e.g., UCamb-Ree) indicate maximum range known for the group; units followed by question marks are isolated occurrences followed generally by an interval with no known representatives. Taxa with ranges to "Ree" are extant. Data are extracted principally from Harland et al. (1967), Moore et al. (1956 et seq.), Sepkoski (1982), Romer (1966), Colbert (1980), Moy-Thomas and Miles (1971), Taylor (1981), and Brasier (1980). KINGDOM MONERA Class Ciliata (cont.) Order Spirotrichia (Tintinnida) (UOrd-Rec) DIVISION CYANOPHYTA ?Class [mertae sedis Order Chitinozoa (Proterozoic?, LOrd-UDev) Class Cyanophyceae Class Actinopoda Order Chroococcales (Archean-Rec) Subclass Radiolaria Order Nostocales (Archean-Ree) Order Polycystina Order Spongiostromales (Archean-Ree) Suborder Spumellaria (MCamb-Rec) Order Stigonematales (LDev-Rec) Suborder Nasselaria (Dev-Ree) Three minor orders KINGDOM ANIMALIA KINGDOM PROTISTA PHYLUM PORIFERA PHYLUM PROTOZOA Class Hexactinellida Order Amphidiscophora (Miss-Ree) Class Rhizopodea Order Hexactinosida (MTrias-Rec) Order Foraminiferida* Order Lyssacinosida (LCamb-Rec) Suborder Allogromiina (UCamb-Ree) Order Lychniscosida (UTrias-Rec) Suborder Textulariina (LCamb-Ree) Class Demospongia Suborder Fusulinina (Ord-Perm) Order Monaxonida (MCamb-Ree) Suborder Miliolina (Sil-Ree) Order Lithistida